My 12 year old daughter has been teaching herself Welsh – a recent birthday present was a good Welsh-English dictionary – we’ve recently been watching a rather bleak Welsh detective series together, and this year she has also become (unlike her father) a bit of a rugby (“rygbi” in Welsh apparently) fanatic so I promised her that if Wales made the World Cup semi-finals I’d do a Welsh-themed post. That’s economics rather than rugby though.

One of the themes of much modern economics literature is things about cities, location, agglomeration, distance and so on. According to Eurostat data, London has the one of the very highest GDPs per capita of any region in the EU¹. The two largest cities in Wales – Cardiff and Swansea – are each less than 200 miles from London. And yet estimated GDP per capita in Wales is only about 40 per cent of that in London and 75 per cent of that in the EU as a whole (71 per cent of the UK as a whole). Productivity in Wales (GDP per hour worked) might be about that of New Zealand.

And yet Wales has much the same policy regime as London. Much the same regulatory environment, same income, consumption, and company tax rates, same currency (and interest rates and banks), same external trade regime, same national government (and as I understand it the Welsh regional administration doesn’t have control of very much), and the same immigration regime. Most of the people are native English speakers (even many of those who also speak Welsh).

Huge populations are free to move to Wales. There are 66 million people in the UK who face no regulatory obstacles to doing so. They could set up firms in Wales. So – for the moment – could people in most of the EU, and all legal migrants to the United Kingdom (with no particular ties to any other UK region) could move to Wales. It isn’t open borders but in practical terms it is much closer to it than almost any sovereign state.

And yet……by and large they don’t. The population of Wales today is only 50 per cent larger than it was in 1900 and only about 5 per cent of the population is born outside the British Isles. Here is the share of Wales in the total population of the Great Britain.

Wales used to have things going for it: plenty of room for sheep (wool and meat were two of our big exports to the urban population of the UK), the world’s largest slate industry, and coal (lots of it) and the associated iron and steel (the latter booming from the start of the 20th century) industries.

But not, it appears, very much at all these days. There is some tourism, some electricity exports (to the rest of Britain) and, of course, a variety of other industries. It all generates tolerable living standards. albeit supported by significant inward fiscal transfers. Unemployment is low, and (by New Zealand or London standards) house prices are fairly low – Swansea (second biggest city) has median house prices around $350000. But people in the rest of the UK, migrants to the UK, and – importantly – actual/potential entrepreneurs don’t seem to find it terribly attractive. Perhaps it would be different if it were an independent country – the Irish company tax regime is apparently eyed up by some. But as it isn’t, one gets a cleaner read on the pure economic geography effects.

It is interesting to wonder what might have happened to Wales if it were an independent country and, all else equal, had had control of its own immigration policy. What if they’d adopted a Canadian or New Zealand immigration policy – or something even more liberal – 20 years ago? Since there are plenty of places in the world much poorer than Wales (or New Zealand), and Wales itself is a small place, presumably they’d have had no trouble attracting people – at least modestly qualified people from places poorer, or less safe, again: China, India, South Africa, the Philippines (to name just four significant source countries for New Zealand). Even if many of the migrants initially saw Wales as backdoor entry to England, if New Zealand’s experience is anything to go by (become a citizen here and you can immediately move to much wealthier Australia) most wouldn’t. Presumably the Welsh building sector would have been a lot bigger, but it isn’t obvious that many more outward-oriented businesses would have chosen Cardiff or Swansea over London or Paris or Amsterdam, even with the rest of Europe more or less on the doorstep.

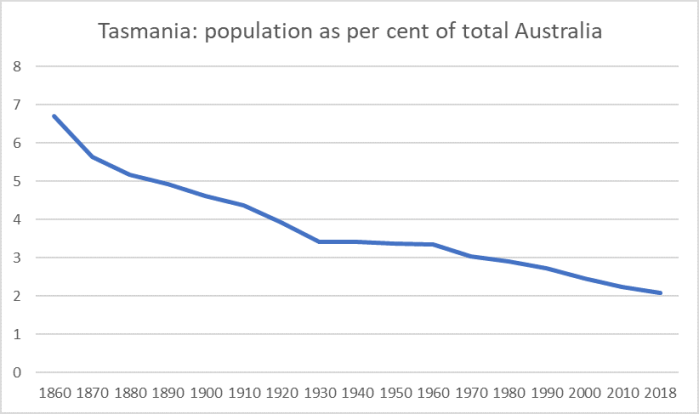

Tasmania is another interesting example. Like Wales, it shares essentially the same policy regime (taxes, currency, external trade, most regulation) with the sovereign country it is a part of, in this case Australia. There is unrestricted mobility for people within Australia, and external migrants – including those from New Zealand – can as readily settle in Tasmania as anywhere else in Australia. Hobart always looks like a really nice place.

Oh, and the population share of the total country is also small. But the fall in the population share has been much sharper than for Wales.

People – and firms – could choose to go to Tasmania but, by and large, they choose not to. It is, after all, quite a way from Melbourne, and you can neither drive nor take a fairly-speedy train. And unlike Wales, Tasmania is close to nothing else: Cardiff is much to closer to Dublin, Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam or even Frankfurt than Hobart is to Adelaide or Sydney. Perhaps even more than Wales, the economic opportunities seem to be mostly in the natural resources (and no big new developments there in recent decades) and a few niche industries that might be there because the founder happens to like living there. GDP per capita in Tasmania is just under 80 per cent of the whole of Australia average.

One could also do an interesting thought experiment as to what might have happened if Tasmania had been an independent country and had its own immigration policy. Even had they just adopted the same policy as Australia did, almost certainly their population today would be materially larger than it now is (Tasmania now has three times the population it had in 1900, while Australia as a whole has more like seven times the 1900 population). Being even smaller than Wales they’d have had no trouble attracting people. But – even more so than for Wales – you are left wondering how many more outward-oriented businesses would have chosen to stay based in little Tasmania (few enough outward-oriented businesses are based in even the big Australian cities).

Are there lessons for New Zealand. Our population has increased almost sixfold since 1900. In that time, we’ve fallen from (roughly) the highest GDP per capita anywhere to somewhere badly trailing the OECD field – and maintaining even that standing only by work long hours per capita.

It looks great to the strain of “big New Zealand” thought that has been around since Vogel at least. But to what end, for New Zealanders?

Think of one last thought experiment. What say we’d agreed a completely common immigration policy with Australia and held that in place for the last few decades? More or less exactly the same number of people would probably have come to Australasia in total, but what do we supposed would have been the split between Australia and New Zealand. It seems only reasonable to assume that a much larger proportion would have gone to Australia (than did). After all, even those who went to Australia had a choice of Tasmania if they wanted cooler climes and a slightly slower pace – but, to a very large extent they didn’t. And we know what New Zealanders themselves – who had ties to this physical places – were choosing over the last 50 years, as hundreds of thousands left for the other side of Tasman.

And had that happened – and perhaps New Zealand’s population was 3 million not almost 5 million – is it likely that any fewer market-driven outward-oriented businesses would be based here than are today. The land, the water, the minerals and the scenery would all still be there. And how much else is there?

As a best guess, if by some exogenous policy intervention there had been another two million people – of moderate skills etc – put in Wales, or another half million in Tasmania, it is difficult to have any confidence that average real incomes in either place would be any larger than they are now. Most probably, they’d be worse off – as say, the residents of Taihape probably would be if some exogenous intervention put another 5000 people there. Having put an extra couple of million people in New Zealand – more remote than Tasmania, much more remote than Wales – and not seen the outward-oriented industries, based on anything other than natural resources growing – we might reasonably assume we (New Zealanders) are poorer as a result.

Smart people are almost always a prerequisite to high incomes, but globally the top tier of incomes seems to focused on industries located in or near big cities, near big population concentrations, or on (finite) natural resources. You can earn a very standard of living from finite natural resources – it is the edge Norway has over the rest of Europe – but it looks pretty insane to confuse the two types of economies (when you have no realistic hope of transitioning from one to the other) and spread natural resource based wealth much more thinly by using policy to actively encourage rapid population growth.

From a narrow economic perspective – and it isn’t of course, the only one the matters – the best thing for people from a lagging economic performance area is to leave. It is what people did from Taihape or Invercargill, from Ireland for many decades, and (more recently and on a really large scale) what people did from New Zealand as a whole. Governments can mess up that picture. In a way the Welsh are fortunate to have a rugby team but not an immigration policy, at least had they had the misfortune to have had policymakers like New Zealand’s.

- Technically Luxembourg tops the table, but since a very large chunk of Luxembourg’s workforce doesn’t live there the numbers aren’t particularly meaningful (sensible comparisons need to take account of all the – typical modest-earning – support services populations need/use where they live).