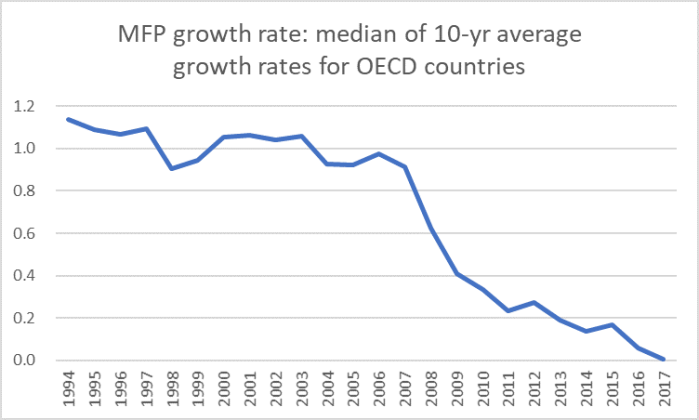

In yesterday’s post I included this chart of multi-factor productivity growth data for the 23 advanced countries the OECD produces estimates for.

One always has to be a bit careful about MFP estimates, which are only as good as the model (and labour and capital input estimates) used to calculate them. But when I looked at the OECD labour productivity growth data – same countries, some period – the picture was strikingly similar.

There is, perhaps, more of a suggestion that productivity growth was already slowing before the events of 2008/09, but still a fairly sharp fall-off in the last decade as well.

I used 10 year average data in these charts because (a) Lord King appeared to be focusing on the pre and post crisis periods (it is now roughly 10 years since the crisis), and (b) because, at least for some countries, there is quite a lot of year-to-year noise, which probably only signifies measurement error. But out of interest, here is what those lines look like calculated as five year averages.

There is some sign of a bit of a rebound in productivity growth, especially for MFP. But (a) most recent periods are probably prone to revisions, and (b) even the latest observations are nowhere near the growth rates being recorded 15 or 20 years ago.

Over the most recent five year periods, New Zealand ranked 4th to last for labour productivity growth, and simply last for MFP growth. We managed 0.0 per cent average annual growth in labour productivity (on this measure) over the five years. By contrast, the median average annual growth rate for labour productivity over that period for the eight former eastern bloc members of the OECD was 2.3 per cent.

The OECD MFP data begin in 1984. That just happens to be when the decade of far-reaching economic reform began in New Zealand. When that reform process started New Zealand was already lagging badly behind the advanced members of the OECD: the OECD doesn’t have MFP levels data, but in terms of real GDP per hour worked, ours in 1984 was only about 75 per cent of the median for the 25 countries for which there is data. The reform process was supposed be about catching-up again. (There are a few people who will dispute that last claim, suggesting that it was only really about ending the decline or even slowing it. But even if some of those individuals really were pessimists even then – perhaps because they think the reforms were not nearly far-reaching enough – it was not the way the story was sold, whether by local politicians or international agencies. Here was the Minister of Finance in 1989.)

So how have we done since 1984? On MFP growth

There are (a few) countries that have done worse than us, but not many (and not mostly ohes that represent much to boast about). You’ll either recall, or have read about, the rank inefficiencies in the New Zealand economy in 1984, But since then we’ve lost ground relative to the typical other advanced OECD countries.

It is only one estimate. Labour productivity – GDP per hour worked – is less model dependent and thus a bit more reliably estimated.

We do a bit less badly on this measure. But the median of these advanced countries – already materially richer/more productive than we were – managed average annual growth of 2.2 per cent per annum over this period while we managed only 1.6 per cent annum. Over 35 years, that amounts to drifting a long way further behind. We are now about 65 per cent of the GDP per hour worked of the median country for which the OECD has data for the whole period.

And one last chart: labour productivity growth since 2000 (when there is data for all of them) of the former eastern-bloc countries and New Zealand.

All of these countries were not-very-market-at-all Communist regimes in 1984 (three weren’t even separate countries). Three of the eight now have average productivity levels equal to or exceeding New Zealand (and the worst only lags us by about 15 per cent). But their growth rates are still much faster than ours.

I’m not here to refight the wars over the broad direction of the reforms New Zealand undertook from the mid 80s to the mid 90s. Most of those reforms were sensible – although I’d nominate three important exceptions. But the fact remains that, appropriate or not, decades on we have made no systematic progress on convergence and catch-up, and are actually drifting ever further behind.

But is there any real sign either of our major political parties care, let alone be willing to identify and initiate changes that might finally turn things around? Not that I can see.

There are global problems and failings – where this post began – and we can’t do anything about fixing those. But we could – and should – be doing much better for our own people, starting (as we do) already so far behind.