Reserve Bank Deputy Governor (responsible for the financial stability portfolio) Geoff Bascand gave a speech in Sydney earlier this week. The title was “Supporting sustainable economic growth through financial stability policy”, but it was really an effort to shore-up support for his boss’s radical bank capital proposals, and in particular to attempt to leave readers and listeners with some sense that there were robust grounds for having minimum core capital ratios materially higher (in headline terms, and in effect given differences in how rules are applied) in New Zealand than in Australia and that in the current climate there was lots of financial system risk.

Despite all the talk of consultation and review, I think it is now safe to assume the Governor won’t be backing down to any material extent. The decision is due to be announced in “the first week of December” and since it is now mid-October the Governor must be very close to taking a final decision – given that they still have to produce a Regulatory Impact Statement and a cost-benefit analysis to buttress whatever choice he makes, and (done reasonably) they take time. Geoff wouldn’t have been sent off to sell the merits of the proposal in public, in Australia, if there were any prospect of any material turning.

The speech opened with a bit of a championing of inflation targeting. It was a bit once over lightly (and Figure 2 leaves quite a bit to be desired) but it wasn’t really his main point. Then we got a strange claim that

Usually our price stability and financial stability policies are complementary. However, the low interest rate world we live in complicates achieving both of our objectives, encouraging a build-up of leverage in the financial system. The persistent decline in long-term and short-term interest rates has supported very high levels of private sector leverage.

He made no effort to justify his claim around monetary policy at all (and recall that at the last MPS the Governor said interest rate mechanisms were working just fine), but the claim around leverage is pretty strange. He says “a build-up of leverage in the financial system”, and yet the speech includes a chart illustrating the increase in the ratio of tier 1 capital to tangible assets over the last decade (that’s a reduction in leverage). Then he talks about “very high levels of private sector leverage”. And yet the chart under that paragraph shows that credit to households and businesses (including agriculture), as a share of GDP, is no higher now than it was in 2007 – levels that did not lead to any particular economywide or systemic problems in New Zealand. As for “leverage” – debt to assets – since asset prices (especially housing) have generally risen faster than GDP, economywide leverage must also have fallen.

For a senior official, with an economics background, responsible for financial stability to show little or no sign of having thought about why equilibrium interest rates now appear to be so low is…..well, quite a gap. He seems confident that monetary conditions are ‘expansionary” but there looks to be little – in credit growth, in asset price inflation, in wider consumer price inflation, in GDP growth rates relative to potential – to support that proposition.

Then he moves onto his attempt to tell a story of heightened (financial stability?) risks.

We recognise that the risks globally are high, and New Zealand is particularly vulnerable to external events. Our economy is quite small – less than a fifth of the size of the Australian economy, and just like Australia, New Zealand is heavily reliant on commodity exports and is very open to financial capital flows. Commodity price movements in world markets determine the value of our key exports, as well as the price we pay for our imports, particularly those that are fuel-related. Monetary policy moves by foreign central banks may generate unfavourable fluctuations in our exchange rates.

Remarkably, that appears to be the only reference to exchange rates in the entire speech – about how unhelpful they can be. There is no sense that, in response to significant external shocks, both New Zealand and Australia have typically found exchange rate adjustment a helpful buffer. I’ll come back to that point.

Then there is more of an attempt to convey a “New Zealand is more vulnerable” story, illustrated by reference to this chart.

It was a strange way to mount an argument – even if one thought the past two shocks (Asia crisis and “GFC”) were predictive of the future – especially as he goes on to acknowledge that Australia’s term of trade (and thus incomes) have been pretty volatile. Debt is nominal, and here is how growth in nominal GDP have compared in the two countries over much the same period.

Neither the frequency of fluctuations nor the amplitude of them look much different between New Zealand and Australia over this period.

Continuing his attempt to play-up differences we hear about nature

In addition to the disruptions in the global economic environment, the New Zealand economy is occasionally affected by weather-related shocks, such as droughts, that constrain the agricultural sector. In the past, we have also suffered severe damage to our infrastructure due to earthquakes.

Well, fine I suppose but (a) they have pretty savage droughts in Australia too, (b) droughts rarely pose any sort of systemic threat to the financial system, (c) Australia is materially more at risk (in economic terms) from climate change, and (c) the earthquakes story is mostly an issue about insurance (including supervision thereof) not banking, and about fiscal policy. Perhaps there is a case for New Zealand to have lower public debt than Australia – although since his boss is champing at the bit for our government to spend and borrow more, I suspect that wasn’t the argument he was trying to make.

Then there is an attempt to play up housing exposures (apparently unaware that household debt ratios are higher in Australia than in New Zealand) and dairy exposures (but, remarkably, with no mention of the exchange rate as buffer), ending with this summary

That’s why maintaining financial stability in this highly vulnerable environment is challenging.

You might suppose that this “highly vulnerable environment” claim might have been backed by, say, stress test results. But I guess they might have – as previous ones have – got in the way of Reserve Bank storytelling. There is little or no credible basis for trying to claim that the New Zealand financial system is unusually or highly vulnerable. Here, after all, is the Deputy Governor’s own chart.

Considerably more core capital than the banks had in the 00s, and we all know how modest the loan losses were in the subsequent, quite severe, recession, even coming after five years of rapid broad-based credit both (without even the moderating and guiding benefit – so the Bank tells us – of Reserve Bank LVR restriction).

And then Bascand moves on more directly to making the case for the Governor’s planned swingeing increases in capital requirements for locally incorporated banks here.

Much of it is just a rehearsal of the same weak arguments we’ve heard all year. There is the “very high” cost of crises, without any attempt to distinguish crisis effects from the misallocation resources in the preceding boom. There attempts to minimise the (national GDP) cost of the insurance – on Bascand’s own numbers from a previous speech perhaps $750 million per annum- an argument which only works on implausibly large estimates of the costs of crises averted.

But there were new weak arguments. Thus

Also, it is worth recalling that capital requirements aren’t like other regulations, in that they don’t create an ‘expense’ for banks. Indeed, in an accounting sense, interest expenses would reduce for the same level of funding.

Does he really expect anyone to take seriously a claim that imposing a whole new funding structure on private sector businesses is really any different in spirit than all manner of other regulations – especially when the Bank’s own numbers assume overall funding costs will increase.

On he ploughs

Our approach from the outset has been to set capital requirements at a level where we can be confident that these costs are outweighed by the benefits of a safer financial system.

But (a) we know from the published documents that the 1 in 200 year threshold was plucked out of the air at the very end of the process, and (b) since there is still no cost-benefit analysis how can they, let alone the public to whom they are accountable, be so “confident”? It would be interesting to hear the Deputy Governor’s response to the recent paper issued by the BIS, reporting the work of various senior central bank officials, which would cast considerable doubt – more generally – on claims that anyone can be ‘confident” that such high minimum requirements as the Governor is planning offer a positive payoff.

The speech moves towards a conclusion with a page and a half on international comparisons.

We set our capital requirements according to the New Zealand specific risk environment, but we also acknowledge how we ‘stack up’ internationally, and why we may need a more capitalised banking system than those in other countries.

Recall that the Bank has never seriously engaged in public with the PWC work suggesting that effective capital requirements in New Zealand are already materially higher than those in most other advanced countries, and they not once produced any careful evaluation demonstrating how their requirements will stack up with those of APRA (in Australia and in their requirements for the entire banking groups). Apart from anything else, APRA is a pretty well-regarded regulator on such things, and the benchmark would provide a useful basis for meaningful debate about just what is appropriate for New Zealand. The short answer, of course, is that New Zealand’s core capital requirements will be materially more demanding than APRA’s, and even the total loss-absorbing capacity will be more demanding. Until now, the Bank has never attempted to articulate why it believes that is appropriate.

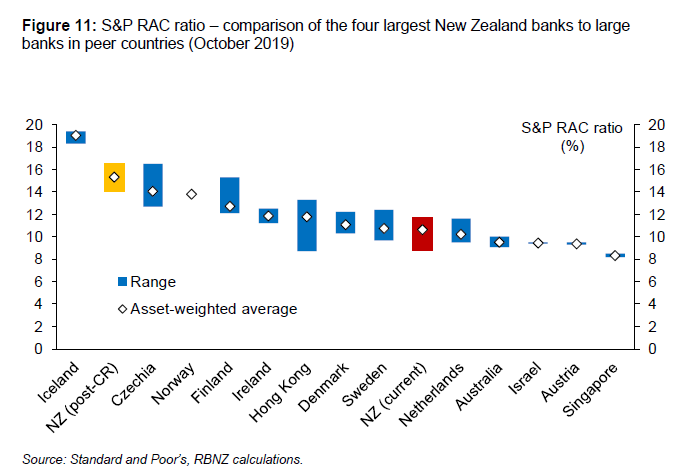

In his speech in Wellington in February (which I wrote about here), Bascand used a chart showing how capital ratios might compare across a selection of countries using S&P risk-adjusted capital (RAC) methodology. He didn’t speak to it much, but it was helpful PR at the time as – the way S&P did things – New Zealand’s current capital requirements produced the lowest capital ratios of any of the countries on the chart, and the Bank’s proposals put us only in the upper quartile of countries.

But the chart has been updated and this is the current version

Now – among this particular range of countries – our current requirements produce ratios (on S&P’s methodology) that are more or less middle of the pack, and the Governor’s proposals would generate – again on the S&P methodology – capital ratios higher than in any of these countries, other than Iceland. And you will recall that tiny Iceland had an absolutely awful, world-scale, financial crisis only a decade ago. Perhaps their caution, extreme risk aversion, is understandable.

Why did the estimated New Zealand capital ratios rise? Because S&P revised their view of New Zealand’s economic and institutional position and concluded that we weren’t quite as bad as they thought previously. Their assessments – the BICRA scores – move around a bit, and which category they put a country in then affects, quite substantially, the risk-weights applying to credit exposures in a particular country. Because S&P think New Zealand is a riskier place than most advanced countries, risk weights used here in doing S&P’s calculations are higher than those in most other places. And even so, on the Governor’s proposals, we still end with among the very highest capital ratios in the world. If you think, for example, that risks here are greater than in Hong Kong (as S&P do) I have bridge for sale. Or as risky, economically, as the UK – where no one, but no one, knows what regime they will be under two week from now…..

International comparisons are hard to do well. But the Reserve Bank has had a great deal of time to do better than this. And yet appears not to have even tried. Not even around comparisons with Australia.

(Oh, and why does S&P take such a dim view of New Zealand. Their methodology has long put great weight on the negative net international investment position. Big changes (worsenings) in such positions do seem to have been associated with subsequent nasty macro adjustments, but New Zealand’s NIIP position has been at (or above) current levels for 30 years now. If it were really an indicator of a serious vulnerability, it would almost certainly have crystallised by now.)

And before leaving this chart, I mentioned earlier that the Deputy Governor mentioned the exchange rate only once, and then unfavourably, in his entire speech. But any serious macroeconomic analyst of financial stability risks recognises that a floating exchange rate can materially increase an economy’s resilience, especially when very bad events happen. Part of the challenge of Greece and Ireland in the last crisis was that a fixed exchange rate (within the euro area) meant they had no capacity to use monetary policy to lean against demand excesses during the boom, and no capacity for the nominal exchange rate to adjust down when things went badly wrong. That isn’t the New Zealand and Australian position. And yet on the Deputy Governor’s chart, almost half the countries have fixed exchange rates (and one other has bound itself to enter the euro in future). That is a legitimate policy choice, but all else equal it would tend to require higher bank capital ratios to cope when things go badly wrong.

The final substantive section of the speech is headed “Relationship with Australia”. Remarkably, it is a mere three sentences long, two of which are really just mechanical statements about “working closely together while pursuing respective national interests”, and nothing at all (for example) about crisis resolution (even though any banking crisis in one of the big four is inevitably going to be trans-Tasman in nature, and highly political). The substance, such as it was, was an attempt to defend taking a tougher line on capital than APRA does.

This is the entire “argument”

Our conservatism, relative to Australia, in our bank capital proposals reflects the higher macroeconomic volatility that we have endured, as I pointed out earlier.

That is just pitifully poor, coming from such a senior figure, speaking to an international audience. And it is not as if it was backed up with detailed discussion in the official consultative documents. No, that’s it.

Remarkably, he doesn’t even engage with the difference between the New Zealand and Australia numbers in his own S&P chart (see above). On S&P’s estimates – and Bascand is quoting them, not me – New Zealand bank Tier One capital ratios already higher than those in Australia, and would be far higher if Orr’s plans are proceeded with. And that within a framework – S&P’s – that already marks New Zealand down as somehow less sound than Australia (we are grouped with Iceland, Malaysia, Mexico and the like). Those differences – alleged greater vulnerabilities – already captured, and we still come out with far higher core capital ratios than Australia.

It is a story – well, more accurately, a line – I don’t find persuasive at all.

When Geoff Bascand gave his speech in Wellington earlier in the year the question of the appropriate degree of conservatism relative to other countries came up. I wrote this.

In the question time yesterday, the Deputy Governor was given the opportunity by a sympathetic questioner to articulate why the Bank should be conservative relative to many other overseas banking regulators. He didn’t offer much: there was a suggestion that New Zealand is particularly subject to shocks, and a claim that New Zealanders are strongly risk-averse (but not evidence, let alone that these preferences are stronger than those of people in other advanced countries). I can identify grounds on which some regulators might sensibly be more conservative than the median:

- if you were in a country with a bad track record of repeated financial crises. But that isn’t New Zealand,

- if you were in a country where much of credit was government-directed (directly or through government-owned banks). But that isn’t New Zealand.

- if you were in a country that depended heavily on foreign trade and yet had a fixed nominal exchange rate. But that isn’t New Zealand.

- or no monetary policy capability of its own. But that isn’t New Zealand.

- or if you were in a country where the public finances were sick. But that isn’t New Zealand,

- or if you were in a country where the big banks were very complex and you weren’t confident you understood the instruments. But that isn’t New Zealand.

- or if you were in a country where the big banks had no cornerstone shareholder, were mutuals, or where the cornerstone shareholder was from a shonky regime. But that isn’t New Zealand.

The case just doesn’t stack up.

In particular – and these are speeches given by the Head of Financial Stability – there is no attempt to engage with the simple fact that the risks the Australian authorities face are much greater than those New Zealand authorities face precisely because our banks are owned by their banks and parental support is a credible prospect in all but the worst shocks. By contrast, there is no cornerstone or dominant shareholder of any of the Australian banks and no one for the Australian authorities to look to if things ever go really badly wrong there. And they could, as they could here.

If this was the best case the Reserve Bank could put up – sending out the least-bad of their senior tier to a professional audience in Australia (it was not a junior manager making the case to the local Rotary Club) – we should be even more worried about what is going on at the Bank, and the ability to top statutory officeholders to make and articulate good policy, than even I had feared. Perhaps we should feel a little sorry for Bascand – he has, after all, to make the case for the boss’s whims – but he is himself a senior figure, a highly-remunerated senior holder of a statutory office. If the case as is threadbare as this speech made it seem, the onus is surely on people on him to do something about it.