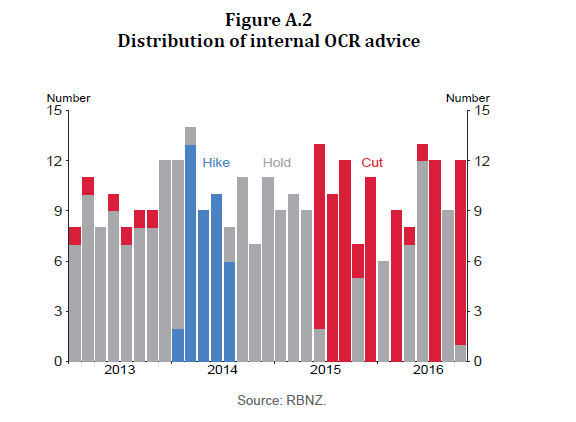

Several years ago the then Reserve Bank Governor went public when there was some criticism around an OCR decision (more so about communications surrounding it) telling us that all his advisers had on that occasion supported his decision. A group of senior staff provide written advice at each OCR decision.

If it was good enough for him to disclose such information when it suited him, I thought it should be fine to have the information disclosed routinely, including for OCR decisions some time in the past. I lodged an OIA request accordingly.

Not that surprisingly, given the Bank’s approach to the OIA, I didn’t get anywhere. They refused to release any other information about previous OCR decisions and, a bit more surprisingly, [as I recalled things, but see below] they managed to get the Ombudsman to provide cover for their refusal.

But in this morning’s Monetary Policy Statement we find almost exactly the data I requested 2.5 years ago, in the form of this chart.

Kudos to the Governor for releasing the information, even (a) this belatedly, and (b) only for the period to the end of 2016, which is now two years ago. We still have no idea what the balance of advice has been over the last couple of years, most of which wasn’t even in the current Governor’s term. But it is better than nothing.

I was among this group of advisers up to and including the March 2014 decision – where I’m pretty sure I was the grey vote (opposed to the OCR increase).

Given that the Governor has now released so much information, I’m tempted to lodge another OIA request for the more recent information – there cannot possibly be any market sensitivity or other problems (defensible under the Act) in knowing that (say) one advisor out of ten favoured an OCR cut six months ago – but as the legislation is about to change perhaps I will leave it for now.

The Governor goes on to note that

Generally, there was a clear majority in the balance of advice. Should the current Reserve Bank Amendment Bill become law, our intention would be to publish the formal votes of the Monetary Policy Committee each time a vote is taken. It is envisaged that a vote would not be called for every meeting, but only when needed.

I found this mildly encouraging, Until now that rhetoric has tended to emphasise very heavily the consensus model the previous Reserve Bank management favoured (under which any differences of view – inevitable in a well-functioning organisation dealing with so much uncertainty – would be obfuscated and kept secret). At least now there is a straightforward explicit statement that the formal votes will be published when such votes are taken. It still isn’t too late for the select committee looking at the bill to amend the legislation to require votes to be taken, and require the number of votes for each position to be published.

There is still a long way to go in getting the Reserve Bank to the point of operating transparently, even reaching (say) the level managed by the Treasury through the Budget process. I still have an Official Information Act request in, now with the Ombudsman, over the Reserve Bank’s refusal to release background papers underpinning claims it made (including around KiwiBuild) in last year’s November Monetary Policy Statement. The Bank has long argued that it would be destabilising, undermining the effectiveness of policy, if anyone ever saw any internal background papers. They claim, citing the OIA itself, that the substantial economic interests of New Zealand would be damaged.

Some months ago the Ombudsman advised a preliminary view that would have continued his office’s longstanding practice of allowing the Bank to keep almost anything associated with monetary policy secret. I made a submission in response that highlighted what appeared to be a serious inconsistency in the way, for example, budget papers are treated. This was some of what I wrote

In general, I think Mr Boshier’s provisional decision, if allowed to stand, would seriously detract from effective accountability for the Reserve Bank, and in particular would expose the Bank routinely to less scrutiny and challenge than Cabinet ministers or government departments receive. That cannot be the intention of the Act. That parallel doesn’t seem to have been taken into account at all in the draft determination.Thus, Cabinet papers underpinning key government announcements are frequently released, sometimes in response to OIA requests and at other times pro-actively. But so too is advice to a Cabinet minister from his or her department. That is so even when, as is often the case, officials have a different view on some or all of the matters for decision from the stance taken by the minister. A classic example, of course, is the pro-active release of a great deal of background material, memos, aide-memoires etc compiled and submitted as part of the Budget formulation process. Many of the working papers in that case may never even have been seen the Secretary to the Treasury but will have been signed out to the office or minister at the level of perhaps a relatively junior manager. Many will have been done in a rush, and be at least as provisional as analysis the Governor receives in preparing for his OCR decision. I’ve been personally involved in both processes.Is it sometimes awkward for the Minister of Finance that his own officials disagreed with some choice the minister made? No doubt. Do ministers sometimes feel called upon to justify their decisions, relative to that official alternative advice? No doubt. But it doesn’t stop either the provision of such dissenting (often quite provisional) analysis and advice, or the release of those background documents.The sorts of arguments the Reserve Bank makes, and which Mr Boshier appears to have accepted, could well be advanced by Cabinet ministers (eg clear messaging about this or that aspect of budgetary or tax policy – all of which are substantial economic interests of the NZ government). If they have advanced such arguments, they have generally not succeeded. And nor should they. Doing so would undermine effective accountability or scrutiny, even though the Minister’s formal accountability might be to Parliament (he has to get his Budget passed).The relationship between the Minister and his or her department officials is closely parallel to that between the Governor of the Reserve Bank – the sole legal decisionmaker (who doesn’t even have to get parliamentary approval of his decisions) – and the staff of (in this case) the Economics and Financial Markets departments of the Bank. One group are advisers, and the other individual is the decisionmaker. The fact that they happen to both part of the same organisation, doesn’t affect the substantive nature of that relationship. Manager and senior managers in the relevant departments are responsible for the quality of the advice given to the Governor, in much the same way that the Secretary is responsible for Treasury’s advice to minister (and at his discretion can allow lower level staff to provide analysis/advice directly to the Minister or his office. I would urge you to substantively reflect on the parallel before reaching your final decision, including reflecting on how (if at all) official advice on input to the OCR is different than official advice (including supporting analysis) on any other aspect of economic policy.Mr Boshier’s argument about potential damage to substantial economic interests itself seems insubstantial, and displaying little understanding of how financial markets (and the market scrutiny of the Reserve Bank) work. It also appears to be based wholly on official perspectives; officials who will routinely oppose transparency (except as they control it). All those who follow, and monitor, the Reserve Bank recognise that there is a huge degree of uncertainty about any of the assumptions the Bank (or other forecasters) make, Indeed, the Bank itself stresses that point. Markets trade changing perceptions of the outlook all the time, each piece of new data slightly adding to the mix. Most monitors of the Reserve Bank (many of whom have previously worked for the Bank) recognise the distinction between analysis and advice, provided as input to the Governor, and the Governor’s own final decision and communication thereof. And since markets – and the Bank – know that any projections are done with huge margins of uncertainty, the pretence that economic outcomes could be substantially damaged by people knowing there were a range of views or analysis is almost laughable. Again, there is also a distinction to be considered between possible institutional interests of the Reserve Bank and the substantial economic interests of New Zealand. You seem to treat those two sets of interests are the same thing, but they are not.

Given that some more months have now passed I hope the Ombudsman is seriously considering these arguments. But whether he is or not, I call on the Governor to take seriously his words about greater openness and more transparency, and put in place proactively a new regime (perhaps for the new MPC) in which staff background papers provided to the Governor and MPC are released, with a suitable lag (perhaps four to six weeks) as a matter of course. Doing so would be a significant step forward, and should help to boost market and public confidence in the Bank. It wouldn’t be terribly radical; it is pretty much what is done for the government’s Budget each year. Perhaps the new Treasury observer could explain to his Bank colleagues how it works, and how Treasury continues to function, continues to offer free and frank advice, even knowing that in time the background work will most probably be open to scrutiny. It is how open democracies, open societies, should work.

I might have some other thoughts tomorrow on more substantive aspects of the Monetary Policy Statement.

UPDATE: Well, it seems that credit is due to the Ombudsman not to the Governor. A few minutes after putting this post, I received this letter from the Bank

Dear Mr Reddell

At the invitation of the Chief Ombudsman, the Reserve Bank has reconsidered your request for the aggregate numbers of MPC members favouring each rate option for each OCR decision since mid-2013. You made this request on 14 March 2016.

On the basis that the requested information has become sufficiently historic, the Reserve Bank has decided it can now release the information. You can find the information on pages 13-14 of today’s Monetary Policy Statement at the following web address www.rbnz.govt.nz/monetary-policy/monetary-policy-statement.