On Newsroom on Friday there was a rather soft article giving a platform to an academic with a pretty strong vested interest in a “nothing to see here, move right along” approach to the People’s Republic of China.

Jason Young is acting director of the Contemporary China Research Centre (CCRC), based at Victoria University. The chair of CCRC is Tony Browne, former New Zealand Ambassador to the PRC, who also just happens to be the chair of the PRC-funded (and controlled) Confucius Institute at Victoria University (CCRC and the Confucius Institute seem to share an administrator as well). The CCRC itself seeems to work hand-in-glove with MFAT, seems to get considerable direct funding from government departments, and its advisory board is largely made up of public servants (MFAT, MBIE, Treasury, NZTE, Asia New Zealand Foundation) plus the chair of Education NZ and the former chair of the New Zealand China Trade Association. (None of this, of course, was in the Newsroom article.) I’ve heard some stories about the role of MFAT in blocking anyone who might prove awkward from consideration for the role of Director.

Perhaps the NZ CCRC does some good work, and holds the odd interesting conference, but when push comes to shove it is hard not to see it as a taxpayer-funded front for the “nothing to see here” line that our politicians and business elites seem committed to. In that respect, it is perhaps worse than the New Zealand China Council – which openly functions as a taxpayer-funded advocacy group, while the CCRC hides behind the veneer of academic independence, integrity etc.

In Friday’s story, the first of Jason Young’s comments was largely pretty reasonable. Asked about the recent testimony in the US and the papers published by the Canadian intelligence services, he noted – as I have – that

Jason Young…. suggests both the Canadian and US reports are based in large part on the ‘Magic Weapons’ report published by Canterbury University professor Anne-Marie Brady last year.

Brady’s report, which detailed concerns about China’s attempts to influence migrant communities and take over ethnic media among other issues, received media coverage at the time.

However, Young says the latest round of coverage has done little to advance the case made by Brady.

“For many of us it’s just more hype around the same types of questions without new evidence.”

Perhaps “a repetition of the same claims in an increasing number of overseas fora” might have been a less-loaded description than “just more hype”, but lets not quibble too much.

Young goes on

Young believes the debate in New Zealand is becoming counterproductive, with opposing sides staking out increasingly polarised positions on the topic.

“We’re not talking about empirics, we’re not furthering the debate, all we are having is a more extreme and radicalised position being put forth…[and] we don’t talk about the bigger issues.”

Which prompts three thoughts:

- first, if you are the director (even acting) of the Contemporary China Research Centre, surely you might have some responsibility for participating in, and actively facilitating debate, and exploration of the evidence, issues, and risks? And yet, there is almost nothing of that sort coming from the CCRC. They seem more focused on getting public servants properly house-trained.

- debate? We have a debate? There isn’t much sign of one in New Zealand at all, most academics maintain a stony silence, and the contrast in that regard with Australia is particularly striking (whether or not you happen to agree with the current, more sceptical, stance of the Australian government).

- As for empirics:

- well no one doubts (because he has acknowledged it) that Jian Yang is a former member of PRC military intelligence structure, a member of the Chinese Communist Party, who also acknowledges that he misrepresented his past on New Zealand immigration forms, reportedly at the encouragement of the PRC authorities. Jian Yang sits in New Zealand’s Parliament.

- no one doubts the effective PRC control of almost all the Chinese language media in New Zealand,

- no one doubts that a former Foreign Minister received a large donation to his mayoral campaign – auctioning, of all things, the works of Xi Jinping – from sources in the PRC,

- no one doubts the ties of senior Labour backbencher Raymond Huo to United Front organisations, or his role in adopting a slogan of Xi Jinping’s for Labour’s ethnic Chinese campaign last year,

- Charles Finny – former senior diplomat, and himself on the CCRC advisory board – observed on TVNZ last year that he knew both Jian Yang and Raymond Huo were close to the PRC Embassy and thus he was always careful what he said around them.

- we know that several of our universities, and a number of high schools, take PRC money and allow the PRC to control appointments, and the content of teaching.

- even abstracting from the Confucius Institute concerns, we know that our universities have made themselves very financially dependent on PRC students.

- we know – it is on public record – that the presidents of both the National and Labour parties have been praising the Chinese Communist Party and Xi Jinping.

- we know that a number of former politicians have ended up in well-remunerated roles in PRC-related entities, and that their continuation in such roles is inconsistent with ever saying anything remotely critical of the PRC.

- and we know that our senior politicians – whether in government or (in the National Party’s case) in Opposition – never ever say anything critical of the PRC regime (in stark and noticeable contrast to the sort of approach their predecessors took to, say, apartheid South Africa, pre-war Germany or Italy, the Soviet Union, and so on).

- So we could debate, for example, the risks and significance of joint research agreements New Zealand universities enter into with PRC institutions – technology transfer, by fair means or foul, being a well-known PRC priority – or we could debate party fundraising in New Zealand, where the limited evidence might be open to various interpretations. Evidence around cyber-attacks isn’t made public. But there is still lots of hard factual material to be going on with. And it is not as if most of the PRC activities are unique to New Zealand – even if perhaps no other advanced country yet has a former PRC intelligence operative in Parliament.

Young goes on

Young says the Government’s messaging on the issue has been “quite minimal”, influenced in part by the sensitivity of allegations related to espionage or foreign influence and the role of our spies.

“The Government has got a responsibility to set China policy, to engage with China, and also have ground rules.”

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has made some steps in that direction, he says, pointing to her recent speech at a China business summit outlining her view of the region and the kind of relationship that was needed.

It would surely be more accurate to say that the Prime Minister – like her predecessors – seems to simply wants to pretend there isn’t an issue (a very different stance than that taken by her Australian Labor counterpart, Bill Shorten). If, perchance, in the quiet of her heart she really does deplore the regime, and worry about its activities here and elsewhere, she owes it to the public to promote an honest open conversation. But, so far, all the evidence is that she is just unbothered – she has uttered not a word about Jian Yang, she promoted Raymond Huo, and so on. Remarkably, the New Zealand airforce is conducting exercises with the PRC air force this week – the same airforce that not a couple of weeks ago was landing long-range bombers on illegally constructed “islands” in the South China Sea (to not a word of concern from New Zealand).

Young’s contributions conclude this way

More generally, Young says the discussion about China needs to be based more on evidence and less on “hyperbole”.

“If someone is claiming New Zealand is the weak link in Five Eyes, what is the claim based on and what is the evidence behind that?

“The argument that New Zealand has somehow changed its security position in relation to Chinese influence, where’s the evidence for that? I can’t see any basis for it.”

It’s not that there’s nothing to talk about, he says: given China holds very different views to New Zealand and other countries, there are valid areas of concern.

But ensuring those concerns are backed up with evidence is critical to stop the debate from losing shape, he says.

Personally, the Five Eyes arguments (generally) seem to me like a bit of a distraction. But so, in a sense, do Dr Young’s comments more generally. There is plenty of hard evidence to be going on with, and a real reluctance apparent among the establishment to turn over stones lest awkward stuff might be uncovered. Dismissing the sorts of issues that Professor Brady, and some others (including Newsroom, who first broke the Jian Yang story) have been raising as “hyperbole” itself looks like another attempt to play distraction, and avoid the real issues. I’m sure Dr Young – and Tony Browne, and Steven Jacobi, and the Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition, the leaders of the Greens and New Zealand First – all know the character of the PRC regime: evil at home, expansionist abroad, working to neutralise and/or divide countries like New Zealand or Australia (or Greece, or the Czech Republic, or…or….or) – but they seem not to care one bit. Or, if they really do care, to be so afraid, and to have lost any sense of self-respect or regard for New Zealand values, that appeasement has just become their watchword. It is shameful.

The Newsroom article in which Dr Young is quoted also talked to another academic keen to downplay the issue; this time an Australian one, James Laurenceson, deputy director of the Australia-China Relations Institute, a think-tank based at a university in Sydney, and funded by large donations from two recent PRC migrants to Australia.

“The New Zealand government’s line tends to be to dampen reports down, but in Australia it goes in the opposite direction,” Laurenceson says.

He also suggests New Zealand has been more willing than Australia to scrutinise the allegations of foreign interference, and is unequivocal about which approach he favours.

“I can’t point to one single advantage of the approach Australia has taken,” Laurenceson says

What he means is that the New Zealand government prefers to ignore the issues altogether and, at least in public, pretend there is simply nothing to see. In Australia, by contrast, an Australian (Labor) Senator was forced to resign for his close ties to the same billionaire who funded ACRI. In Australia, in a bipartisan effort, the intelligence and security committee has recently released a 400 page report on the planned new laws designed to limit foreign government intervention and influence activities. Yes, some Australian exporters appear to be paying a price, but sometimes doing the right thing – standing up for your own country and its values, not just for the next dollar – will cost those who parley with evil. While Jacinda Ardern and Simon Bridges, aided and abetted by taxpayer funded bodies like the China Council and the CCRC, pretend there is just nothing to see.

There was a nice contrast to the New Zealand approach in The Australian newspaper on Saturday, in a column by their respected foreign editor Greg Sheridan. For example

The last couple of weeks are a good indication of things to come. The range of our disagreements with Beijing in this period has been bewildering.

Beijing hates the foreign interference legislation. It hates that [Liberal MP, Andrew] Hastie under parliamentary privilege named a Chinese national resident in Australia as the suspect in a US case regarding a bribe paid to a former senior figure at the UN. It hates the fact that Canberra prevailed on Solomon Islands to refuse a Chinese bid to build an underwater internet cable. It hates that US court proceedings revealing alleged Chinese bribes in Papua New Guinea were front-page news in Australia.

It hates that Defence Minister Marise Payne rightly criticised the deployment of long-range bomber aircraft into islands that Beijing has illegally occupied in the South China Sea. It hates that, Beijing having ordered Qantas to refer to Taiwan as “Taiwan, China”, Payne said Qantas should not be bullied by governments and that Australia had “always called Taiwan, Taiwan”.

Beijing also didn’t like Payne’s reiteration of Canberra’s longstanding position on disputed territories in the South China Sea at the recent Shangri-La Dialogue, nor did it like her pointedly saying that countries should be allowed to express such concerns without being intimidated, coerced and bullied by other nations.

Beijing, like everyone else, understood who she was talking about.

In all these matters, the Turnbull government has taken the only position any self-respecting government could.

A self-respecting government, but not a New Zealand one.

After I’d read the Newsroom article, I found a recent podcast of a discussion between Jason Young and James Laurenceson. It was another attempt by Jason Young – remember all that taxpayer funding at stake, and those close ties to the Confucius Institute – to play down the issues in New Zealand (to be clear, I’m not suggesting Young’s views are determined by financial incentives, but that he holds the role he does because he holds views that aren’t going to rock the boat with MFAT, the government, or the PRC).

In the course of the discussion – in which he also highlighted the difference between New Zealand and Australia, in the depth of commentary and debate over there, without apparently seeing any role for people like him to take it deeper here – he attempted to draw a distinction between influence and interference. But again, it was all about an attempt at minimalisation and trivialisation. He accepts that PRC influence-seeking activities go on here, but then minimises that by suggesting “everyone does it” – as if the character of the PRC regime is something we should be indifferent to, relative to say the UK, France, Germany, India, Singapore or whoever. The issues aren’t just about process, but content, character, and so on. As far as “intervention” is concerned, Young asserted that the “bar was not yet met” on such claims. Perhaps that is a definitional issue, but when there is a former PLA intelligence operative in our Parliament, when another MP uses Xi Jinping slogans to advance his party’s cause (himself being associated with various United Front bodies), and when our politicians (and academics apparently) are too scared to speak out – we never had a problem criticising South African apartheid or French nuclear testing – I think we all know that interference has happened. Just because the mugger with the baseball bat doesn’t actually hit you, doesn’t mean that when you handover your wallet, the mugger hasn’t interfered.

Finally, as if to make Jason Young’s point about the greater depth and seriousness of the debate and analysis in Australia, there is even a better class of material to debate. Professor Hugh White is an academic at ANU, former deputy head of Australia’s Defence Department, and a long-time writer on strategic issues in east Asia and Australia. He has been criticised for, as some argue, being too ready to assert that Australia needs to recognise that the the PRC is already, or soon will be, the dominant power in East Asia, and re-align accordingly, making nice with the PRC and moving away from the US.

But he had a bracing short commentary out a few days ago, Australia’s real choice about China.

Australia’s problem with China is bigger and simpler than we think, and thus harder to solve. It isn’t that Beijing doesn’t like Julie Bishop, or that it’s offended by our new political interference legislation, or that it’s building impressive new armed forces, or staking claims in the South China Sea. It’s that China wants to replace the United States as the primary power in East Asia, and we don’t want that to happen. We want America to remain the primary power because we don’t want to live under China’s shadow.

And that’s a big problem for Beijing. Its ambition for regional leadership isn’t something the Chinese are willing to compromise. Nothing—not even economic growth—is more important to them. So our opposition is a big fault line running through the relationship.

This shouldn’t come as news. China’s ambition, and the problems it poses for Australia, have been unmistakably obvious for a decade, but most of us have been in denial about it.

ending, after noting his real doubts that the US is willing to pay a price to retain its position

…at the end of last year, the government announced new laws to prevent covert political interference, clearly aimed at China.

That’s when China decided to exert a little pressure. It didn’t take long for Canberra to get the message. By early this year, Turnbull and Bishop were already backpedalling hard. They tried to deny that the foreign interference laws were aimed at China, talked up China’s positive contribution to the region, and even took the remarkable step of repudiating Washington’s new tough language about China as a rival and a threat.

But Beijing hasn’t been assuaged, and so the pressure is still on. It isn’t much so far—at least compared to what they could do if they wanted to cause us real pain. But it’s enough to remind Canberra—and the rest of us—what national power means. It means the capacity to impose costs on another country at relatively low cost to oneself, and China now has that in abundance. We’re being warned.

This problem isn’t going to go away, so we have to make some choices. Now we know that China is serious, what price are we willing to pay to resist it, and how far are we prepared to go? Those choices must be based on a realistic assessment of China’s power and ambitions, and of the cost we will incur by opposing them.

We haven’t had that kind of realistic assessment until now, in part because it has been so easy to accuse those who recognise the reality of China’s power and ambition as advocating surrender to it. That is, of course, absurd. And now, perhaps, we can put this absurdity behind us and start seriously to discuss how to deal with the biggest foreign policy challenge since at least World War Two.

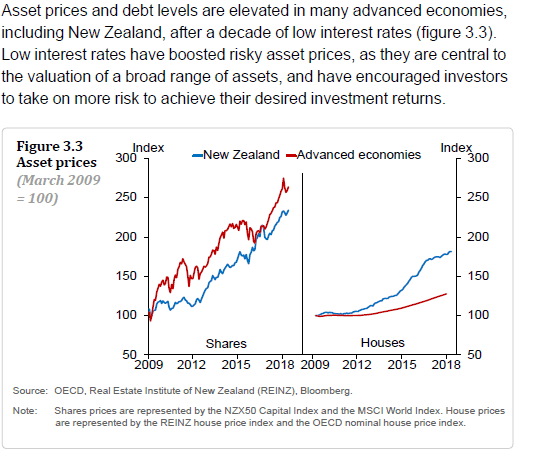

It isn’t clear that the issues are really any different for New Zealand, including because of the absolute importance of our relationship with Australia. But there is no New Zealand politician or, it seems, academic willing to actually make this straightforward point, and lead a debate about the implications, and choices, for New Zealand. Perhaps where I depart from White is that I think he overstates the economic threat the PRC could pose to either New Zealand or Australia, other than in the short-term and in a handful of sectors that have dealt with the devil and left themselves over-exposed. Countries make an sustain their own prosperity.

But isn’t that the sort of debate and analysis one might hope for from a body labelled Contemporary China Research Centre. Or the sort of leadership one might hope for from our politicians. New Zealand’s current approach – keep silent, pretend there isn’t an issue, lie (in essence) about the character of the regime, and appease like anything – wasn’t the right approach in the 1930s, and isn’t likely to be now. It is a shameful betrayal of our interests, our values, and – not incidentally – of our friends in the free and democratic parts of east Asia.