The Prime Minister gave what she billed as a “pre-Budget” speech yesterday to the leading business lobby group, Businss New Zealand. It was, I’m pretty sure, her first prime ministerial speech mainly on economic matters. In introducing her speech she indicated that she would

outline our plans for the economy and how we want to partner with New Zealand businesses to bring about transformative change for the good of all New Zealanders.

and a few sentences later she added

We are committed to enabling a strong economy, to being fiscally responsible and to providing certainty. We have a clear focus on sustainable economic development, supporting regional economies, increasing exports, lifting wages and delivering greater fairness in our society.

But in the rest of the speech there was almost nothing there. There were slogans, and feel-good phrases. But there was no plans for the economy. No plans to lift productivity – a point she touched on not infrequently during the election campaign – and barely even an acknowledgement of the problem, no plans to reverse the decline in the export/import shares of GDP in New Zealand, and no sign that she – or her advisers or her Minister of Finance – have a serious well thought-through story of how New Zealand ended up underperforming as badly as it has done, let alone how we might reverse the underperformance.

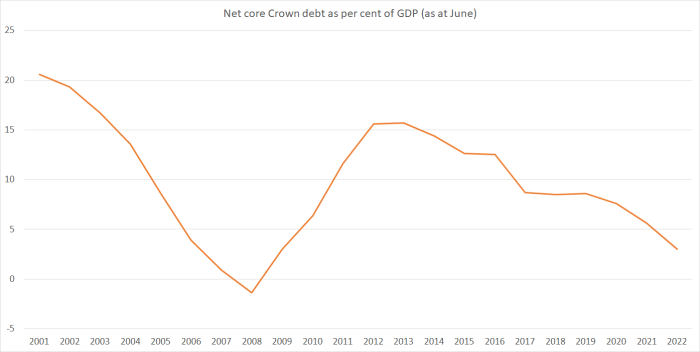

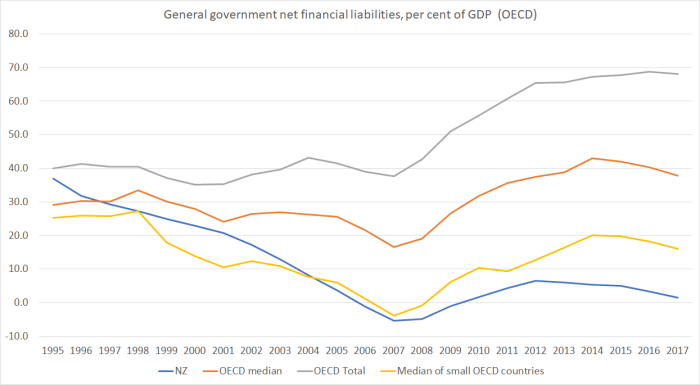

Governments of both political parties deserve credit for keeping the government’s finances more or less in order. As I noted yesterday, that is more than most large OECD countries have managed in recent decades. But it isn’t a substitute for policies that might finally offer a credible path out of the 70 years of relative economic decline – drifting a bit further behind even as every country is richer than it was – that New Zealand has experienced.

Instead, we get attempts to shift the goalposts, aided and abetted by The Treasury.

On that score how we measure our success is important. In the past we have used economic growth as a sign of success. And yet a generation of New Zealanders can no longer afford a home. Some of our kids are growing up living in cars. Our levels of child poverty and homelessness in this country are much too high.

We all want a strong economy. But why do we want it? What is it for? It is vital that we remember the true purpose of having a strong economy is for us all to have better lives.

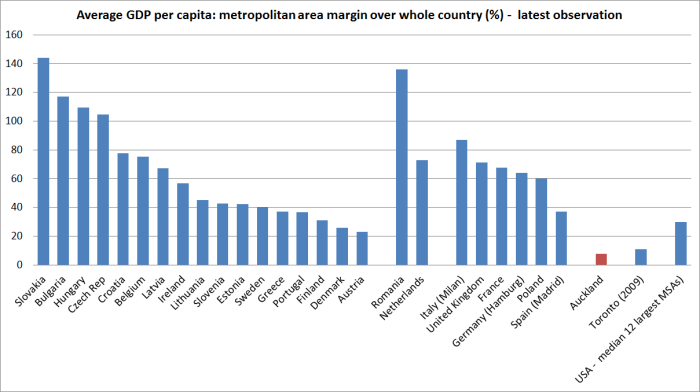

Well, sure. GDP isn’t an end in itself, but it (and cognate measures) are a pretty important means to those ends, and a reflection of how well a society is providing for itself. And how does the Prime Minister suppose that the crushing specifics of (New Zealand) poverty 100 years ago – when New Zealand was the richest country on earth – became largely non-existent today? By achieving sustained productivity growth. And if we now score badly on some of the poverty indicator measures, it isn’t entirely surprising when productivity (real GDP per hour worked) isn’t even two-thirds of that in countries like France, Germany, the United States, and the Netherlands. When it now also lags well behind Australia too.

In her speech, she claims that her plans are already clear

We have already spelled out our ambitious agenda to improve the wellbeing and living standards of New Zealanders through sustainable, productive and inclusive growth. Now we want to work with business and investors to get on with it and to deliver shared prosperity for all.

and

We will encourage the economy to flourish, but not at the expense of damaging our sovereignty, our natural resources or people’s well-being. Our plans have been spelled out from the beginning, in the Speech from the Throne, in the first 100-days plan, and very soon you will see more detail in our first Budget. ……

You will see a clear plan to build a robust, more resilient economy. You will see a strong focus on delivering economic growth, on running sustainable surpluses and reducing net debt as a proportion of GDP.

There was little of substance on this score in the Speech from the Throne. And much as I wish it were otherwise, I won’t be holding my breath waiting for the “clear plan” for stronger sustained real economic (and productivity) growth in the Budget. There is nothing in anything the government has said so far that suggests they or their advisers really grasp the issues. Quite why simply wishing businesses would “get on with it” would now be expected to produce better outcomes than we’ve seen in recent decades is a bit beyond me.

Of course, there are nods in the direction of things Labour (or their partners believe in)

My Government is keen to future-proof our economy, to have both budget sustainability and environmental sustainability, to prepare people for climate change and the fact that 40 percent of today’s jobs will not exist in a few decades.

I’d love to see some data on what proportion of jobs that existed 40 years ago don’t exist today (the majority of the jobs that existed in the Reserve Bank I joined in 1983 don’t exist any more). But while the government worries about work – setting up a new tripartite forum involving the CTU and Business New Zealand – actual employment rates don’t seem to be the problem.

(Lack of) productivity is. It is productivity growth that underpins any long-term growth in real incomes and living standards.

There is talk of skills, when OECD data have shown that New Zealander workers have some of the highest levels of skills anywhere in the OECD (indeed, the chair of the Productivity Commission was retweeting an OECD chart to that effect just a few days ago).

There is talk that “no-one has the same job for life any more”. Perhaps, but there is data overseas suggesting that average length of time with a single employer is little different now than it was 30 years ago.

There is talk of “lifting R&D spending”, and the government has out for consultation at present its plan for new R&D subsidies, but no sense that the Prime Minister or her advisers have thought at all hard about why firms might not have found it worthwhile to do more R&D spending (or why, by contrast, firms in some rich countries with no R&D subsidies do a great deal).

There was lot of rhetoric

Business can be assured that this Government will support those who produce goods and services, export and provide decent jobs for New Zealanders.

But little substance, and nothing that shows signs of pulling it all together into a coherent narrative.

And, for all the mentions of climate change and related issues, nothing at all about how faster overall productivity growth – and a stronger export/import orientation – might be achieved in the face her government’s commitments to sharply reducing net emissions in a country with high marginal abatement costs. “High marginal abatement costs” has meaning: it costs to do this stuff, and the cost is likely to be reflected in lower levels of economic activity (and productivity) than otherwise. Perhaps the government disagrees – and perhaps her audience were too polite to challenge her – but there is nothing in the speech suggesting she has thought hard about squaring that circle. There seems to be lots of wishful thinking, and not much substance.

And then there were “the regions”

And the regions need not fear they will be neglected. We have committed $1 billion per annum towards the new Provincial Growth Fund and over coming months there will be more detail about how this spending will be targeted. After all, nearly half of us live outside our main cities and our provinces also need to thrive if New Zealand is to do well.

The Provincial Growth Fund aims to enhance economic development opportunities, create sustainable jobs, contribute to community well-being, lift the productivity potential of regions, and help meet New Zealand’s climate change targets.

There might be a bit of a lolly scramble, redistributing the current cake. But there is nothing from the government, or from the architects of the PGF – and nothing in the announcements to data (eg here and here) suggesting that the government has any concept of how overall productivity growth rates, nationwide or in the regions, might be lifted. (And not once was the real exchange rate mentioned.)

Perhaps defenders of the government would push back on one or another point. But there is no sign of any sort of integrated narrative – a rich understanding of how we got to our current sustained underperformance or, reflecting that, how might hope to reverse the decline. No doubt in an attempt to woo her business audience, there weren’t even any references to tax system changes (CGT and all that) in this economic speech.

Perhaps that isn’t entirely the government’s fault. The Treasury seems at sea as well. But we don’t elect bureaucrats, and we do elect governments.

Of course, I wouldn’t want to be misinterpreted as suggesting that the Opposition was any less bad. The new Leader of the Opposition also gave his first economic speech this week. There were a few bits where I was nodding my head as I read

Labour and NZ First are more focused on government intervention. They believe they know how to run your businesses better than you do.

Shane Jones’ $1 billion Provincial Growth Fund is a good example. It’s terrible policy.

Now I’m sure there are some worthy projects that will get funded. But it will shift businesses from focusing on becoming more productive to chasing a subsidy from Matua Shane.

That’s not how to drive long-term productivity improvements.

Couldn’t disagree, but what did Bridges have to offer

When I was Economic Development Minister, our plan for the economy was set out in the Business Growth Agenda.

The BGA comprised over 500 different initiatives all designed to make it easier to do business by investing in infrastructure, removing red tape, and helping Kiwis develop the skills needed in a modern economy.

Some of those were big, some were small. I’ll admit some weren’t as exciting spending a billion dollars every year.

But together they were effective.

New Zealand has one of the best performing economies in the developed world.

500 initiatives and we still had barely any productivity growth in the last five years. And, as I recall, one of the BGA goals was a big increase in the export (and, presumably, import) share of GDP: those shares have actually been shrinking. Productivity levels languish miles behind the better advanced economis, and the gaps showed no sign of closing.

He ends

New Zealand is a great country. And if we maintain our direction and momentum of recent years we can make it even better for our kids.

Moving into opposition is a chance for National to look at our position on certain issues, and understand the things that New Zealanders want us to focus on.

Although the one thing I hope you’ll take from my speech is we won’t be changing our focus on the economy.

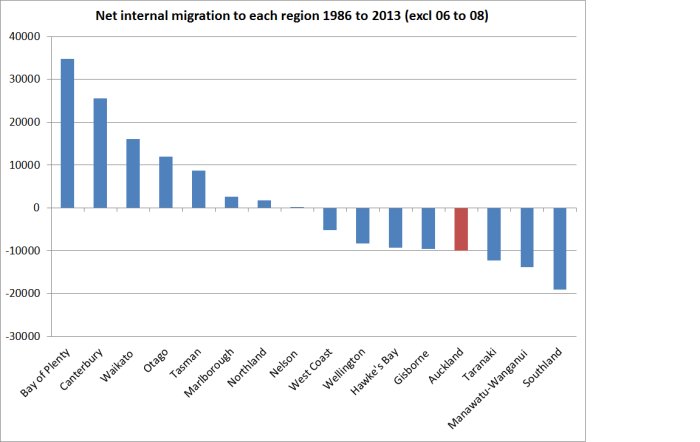

If we don’t start seeing a lot more hard-headed thinking – and a quite material change of direction – from our political leaders and their advisers, a country that really was once the best place in the world to bring up kids, will increasingly be a country where wise parents can only counsel their kids that if they want first world living standards, the best option is to leave. In my lifetime, 970000 (net) have already done so. The Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition – representing two sides of the same coin when it comes to our economic failure – are younger than me, but in just the 37 years the Prime Minister has lived, a net 780000 of our fellow New Zealanders have left. Outflows of that scale – which, of course, ebb and flow with short-term developments in Australia and here – just don’t happen in normal, successful, countries.

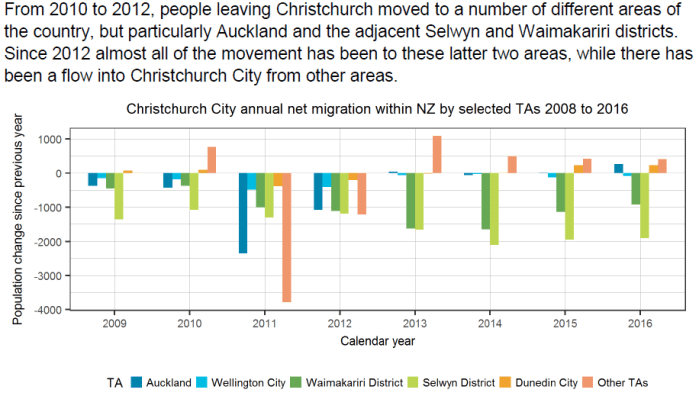

There is a fascinating picture of Christchurch following the earthquakes, including the continuing losses in recent years to neighbouring Selwyn and Waimakariri.

There is a fascinating picture of Christchurch following the earthquakes, including the continuing losses in recent years to neighbouring Selwyn and Waimakariri.

As I observed then, we didn’t know what had happened since 2013. Perhaps things had turned around? But the new Treasury estimates suggest that if anything the outflow – still modest each year – may have accelerated.

As I observed then, we didn’t know what had happened since 2013. Perhaps things had turned around? But the new Treasury estimates suggest that if anything the outflow – still modest each year – may have accelerated.