Late last week the New Zealand Initiative released its report Who Guards the Guards? Regulatory Governance in New Zealand which has a particular focus on the Financial Markets Authoritiy, the Commerce Commission, and (in its financial regulatory/supervisory roles only) the Reserve Bank. All three are important economic regulators and, if we are going to have such entities, it is important that they are well-governed, and performing excellently (with associated accountability and transparency) the roles Parliament assigned to them.

As part of putting together the report, the New Zealand Initiative undertook a survey

To assess how well our regulators are respected, we surveyed New Zealand’s 200 largest businesses by revenue, together with those members of The New Zealand Initiative not otherwise included as members of the ‘top 200’. In practical terms, this approach allowed adding a sample of New Zealand’s leading professional services firms – accountants, lawyers and investment bankers – into the pool of businesses covered by our survey. Only one response per organisation was permitted.

And this is what the survey covered

We asked survey respondents both to:

a. rank the regulators they interact with based on their overall respect for them; and

b. rate the performance of the three regulators most important to their respective businesses against a range of KPIs.

The KPIs were based on a combination of the best practice principles identified by the Australian Productivity Commission’s Regulator Audit Framework, and from a similar survey to our own commissioned by the New Zealand Productivity Commission for its 2014 report. The questions were designed to obtain a broad view of regulatory performance, and as such did not enquire into the merits of individual regulatory decisions or the fitness-for-purpose of individual regulators.

Rather, the KPIs cover issues like commerciality, communications, consistency, predictability, accountability, and so on.

For some regulatory agencies – there were 20+ covered – there were lots of responses: some regulation is pretty pervasive. For others with a very sector-specific role, including the Reserve Bank, there were only a relatively small number of responses (8) – but it seems likely that all the major banks and some other smaller institutions will have responded.

The Initiative is clear that it is a survey of the regulated. That is not the only, or even the most important, perspective in assessing a regulatory agency. Regulatory agencies are supposed to work in the public interest, as defined by Parliament, and that means constraining the actions/choices of individuals and firms. Regulation is intended to prevent people doing stuff they would otherwise choose to do, or compel them to do stuff they would otherwise not choose to do. In other words, one should worry if a regulator is popular with those it regulates. Indeed, one of the big risks in any regulatory system is that the regulator and the regulated form too cozy a relationship – in which there is some mix of regulators making life easy for the the regulated (eg coming to identify more with the interests and perspectives of the regulators) or regulators in effect working with the bigger and more connected/established of the regulated entities to make new entry and competition less easy than it should be.

The Initiative acknowledges the point to some extent

Of course, we can expect regulators to be unpopular at times with the businesses they regulate. It is, after all, their job to place boundaries on what businesses can and cannot do. But just as we expect communities to respect the police, we should also expect the regulators of commerce to have the respect of the businesses they regulate.

Personally, I’m not sure I’d go that far. I don’t expect “communities to respect the police”, but expect (well, vainly wish) the Police to earn the trust and respect of the community. But whether or not “respect” is quite the right word, regulated entities should be able to offer some insights that are useful in evaluating regulatory institutions. And that is perhaps particularly so when, as in this exercise, the survey covers a wide range of regulatory institutions at the same time. If one institution scores particularly badly relative to others – particularly others in somewhat similar fields – it should at least provide the basis for asking some pretty hard questions about the performance of that agency, and of those responsible for it (officials, Boards, Ministers etc).

In this survey, the Reserve Bank’s financial regulatory areas scores astonishingly badly. I first saw the results months ago when I was asked for comments on the draft report, but even with that memory in mind, rereading the Reserve Bank results (from p 60) over the weekend made pretty shocking reading.

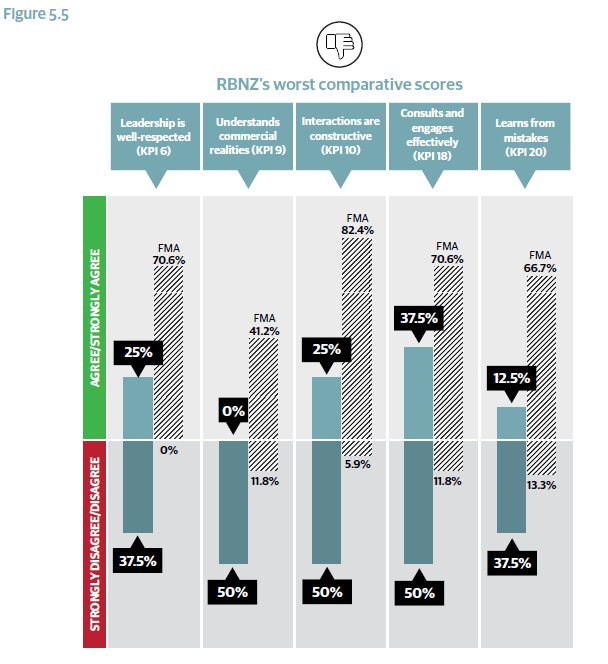

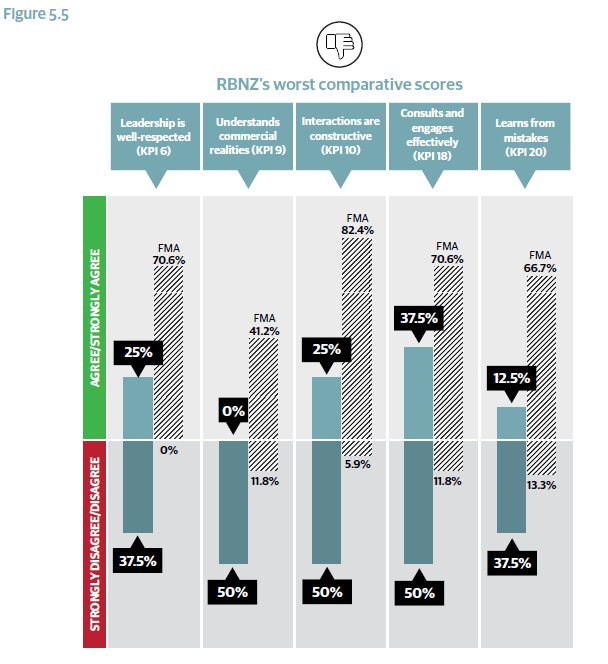

Here is one chart from the report, comparing Reserve Bank and FMA results for the KPIs where the Reserve Bank scores worst.

In summary

In the ratings, the RBNZ’s overall performance across the 23 KPIs was poor. On average, just 28.6% of respondents ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that the RBNZ met the KPIs and 36% ‘disagreed’ or ‘strongly disagreed’. These figures compare very unfavourably with the FMA’s average scores of 60.8% and 10.3%, respectively. They also compare unfavourably (though less so) with the Commerce Commission’s averages of 39.9% and 25.8%, respectively.

There simply isn’t much positive to say.

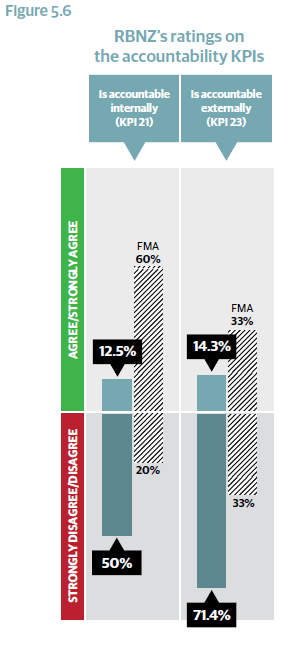

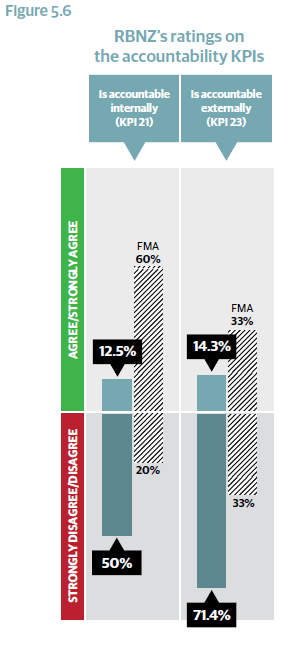

One of my consistent themes has been the lack of accountability of the Reserve Bank, across all its functions. The regulated entities seem to share those concerns.

As part of the survey, interviews were also conducted to fill out the picture the data themselves provided.

Like the survey results, the views of interviewees were also largely [although not exclusively] negative.

The criticisms related both to the RBNZ’s capabilities and processes, and the substance of its regulatory decision-making.

In relation to process and capability, criticisms included the following issues:

a. Lack of consistency in process: One respondent noted that the internal processes of the RBNZ’s prudential supervision department, which is responsible for prudential supervision, can be ‘random’. The respondent referred to long delays between steps in a process involving regulated entities, followed by the imposition of requirements for more-or-less immediate action from them.

b. Lack of relevant financial markets expertise among staff: This was a common

theme. One respondent noted that until the 2000s, there was “regular interchange

of staff between the banks and RBNZ,” meaning RBNZ regulatory staff had firsthand finance industry expertise. But this has changed with the banks moving their head offices to Auckland and the RBNZ based in Wellington. As one respondent said, “They will always struggle to get good people [with financial markets expertise] in Wellington, especially with the banks now in Auckland… this makes interchange impossible.” Another said, “RBNZ [staff are] completely divorced from the reality of how things are done.” More colourfully, another said, “[RBNZ] is all a little archaic… Entrenched people don’t get challenged.” Another said, “On the insurance side, the level of capability is less than with the banks. There is a potential risk to policyholder protection. RBNZ ends up just focussing on the minutiae.”

c. Lack of commerciality: This concern is allied to both the expertise issue noted above, and the materiality issue noted below. As one respondent said about the RBNZ’s ‘deafness’ to the need for a materiality threshold before a matter becomes a breach of a bank’s conditions of registration, “RBNZ says, ‘If it’s not material just disclose it’. But that’s a regulator way of thinking. They don’t understand the commercial, reputational implications.”

d. Unwillingness to consult or engage: As one respondent said, “I would call them out for not truly consulting.” Another said, “The RBNZ upholds independence to the point that it precludes constructive dialogue.” Several respondents drew a contrast with the FMA, noting that the RBNZ was happy to issue hundreds of pages of “prescriptive, black letter requirements,” but “without much or any guidance” for the banks on their application. One respondent did note, however, that the RBNZ “isn’t resourced to spend time doing this [issuing guidance].”

e. Lack of internal accountability: Several respondents perceived a lack of oversight from the most immediate past Governor, Alan Bollard, in either engaging with the banks over concerns about prudential regulation or trying to resolve them. One respondent noted, “Staff are often running around doing things without serious scrutiny from above.” Another said there is a group “with no accountability within the RBNZ… They favour form over substance and seem to enjoy exercising power.” Another commented it was “unclear how much information flowed up to the RBNZ Board,” but that if the Governor were accountable to the board for prudential regulation, then the board “could be useful in pulling up entrenched behaviour.” Another noted that the RBNZ’s governance structure meant it did not benefit from outside perspectives: “[t]he value of diverse thinking is to challenge, so you don’t get capture by one person’s view.”

Two main criticisms were made in relation to substance:

a. Materiality thresholds: Several respondents highlighted the lack of a ‘materiality

threshold’ before RBNZ approval is needed either for:

• changes to banks’ internal risk models in the Conditions for Registration of

banks; or

• changes to functions outsourced to related parties.

One respondent noted that without a materiality threshold, the new requirement

for a compendium of outsourced functions – and for approval of any change to

outsourcing arrangements with a related entity – could lead the Australian-owned

banks to cease outsourcing functions to related entities, thereby increasing costs and

harming customers. Several respondents noted that the lack of a materiality threshold could be attributed to a lack of trust in the banks by the RBNZ staff responsible for prudential regulatory decisions. As one respondent put it, this led the RBNZ to “insist on approving absolutely everything.”

Although this view was not shared by all banks, one respondent noted that even

APRA – long regarded as a more heavyhanded, intrusive regulator than the RBNZ

– was “now more reasonable to deal with than the RBNZ.”

b. Black letter approach: Along with the lack of a materiality threshold in the RBNZ’s

regulatory regime, several respondents commented on the RBNZ’s “black letter”

approach to interpreting its rules: “If RBNZ had two or three public policy experts

who could bring a ‘purposive approach’ to interpretation, that would be hugely positive.” Another said, “[The RBNZ] has an overly legalistic approach which ignores the purpose of the legislation,” and that “what they’re doing undermines [public] confidence over things that are of no risk.” Several survey recipients noted that this was in stark contrast to APRA’s approach to public disclosure in Australia.

Another respondent put the concern differently, saying the problem was less

about the RBNZ’s ‘black letter’ approach to its rules, and the opaqueness of the rules,

and more about the lack of guidelines from the RBNZ explaining them, an issue the

respondent put down to a lack of resources.

There is more detail there than most readers will be interested in. I include it because the overall effect builds from the relentness of the critical comment. I’m not even sure I agree with everything in those comments – but they are clearly perspectives held by regulated entities – and I suspect that reference to Alan Bollard is really intended to refer to Graeme Wheeler. But taken as a whole, it is an astonishingly critical set of comments and survey results, that most reflect very poorly on:

- former Governor, Graeme Wheeler,

- former Head of Financial Stability (and Deputy Governor and “acting Governor” Grant Spencer),

- longserving head of prudential supervision, Toby Fiennes

- the Reserve Bank’s Board, including particularly the past and present chairs, Rod Carr (who had had a commercial and banking background) and Neil Quigley.

And given the enthusiasm of the Bank to emphasis the role of the Governing Committee in recent years, it probably isn’t a great look for the new Head of Financial Stability, and Deputy Governor, Geoff Bascand – he of no banking/markets experience, no commercial perspective, and little regulatory experience – who sat with Wheeler and Spencer on the Governing Committee over the previous four years.

One would hope that the new Governor, the new Minister, and the Treasury and the Board, are taking these results very seriously, and using them to, inter alia inform the shaping of Stage 2 of the review of the Reserve Bank Act. I’ve not heard any journalist report that they’ve approached the Reserve Bank – or the Board or the Minister – for comment on the report and the Bank-specific results. But such questions need to be asked, and if the Bank simply refuses to respond or engage that in itself would be (sadly)telling.

In the report the New Zealand Initiative authors make much of comparisons with the FMA. In respect of the survey results, that seems largely fair. The data are as they are. But as I’ve noted in commenting a while ago on an op-ed Roger Partridge did foreshadowing this report, I’m not entirely convinced (nor am I fully convinced about the criticisms of the FMA’s predecessor the Securities Commission, which was asked to do a different job).

Partridge cites the Financial Markets Authority as a better model. In many respects, the FMA is structured like a corporate: the Minister appoints (and can dismiss) part-time Board members, and the Board hires a chief executive. But it is worth remembering that the FMA has quite limited policymaking powers: most policy is made by the Minister, whose primary advisers on those matters are MBIE. The FMA is largely an implementation and enforcement agency. That is a quite different assignment of powers than currently exists for the Reserve Bank’s regulatory functions (especially around banks). Also unaddressed are the potentially serious conflict of interest issues around the FMA Board, in its decisionmaking role. More than half the Board members appear to be actively involved in financial markets type activities (directly or as advisers), and even if (as I’m sure happens) individuals recuse themselves from individual cases in which they may have direct associations) it is, nonetheless, a governance body made up largely of those with direct interests that won’t necessarily always align well with the public interest.

Reasonable people can reach different views on the performance of the FMA. I gather many people are currently quite pleased with it, although my own limited exposure – as a superannuation fund trustee dealing with some egregious historical abuses of power and breaches of trust deeds – leaves me underwhelmed. It is certainly a model that should be looked at in reforming Reserve Bank governance – it is, after all, the other key financial system regulator – but I’m less sure that it is a readily workable model for the prudential functions, even with big changes in the overall structure of the Reserve Bank, and some reassignment of powers. It certainly couldn’t operate well if both monetary policy and the regulatory functions are left in the same institution. It doesn’t seem to be a model followed in any other country. And it isn’t necessary to deal with the core problem in the current system: too much power is concentrated in a single person’s hands. In a standalone regulatory agency, I suspect an executive board – akin to the APRA model – is likely to be an (inevitably imperfect) better model.

Whatever the precise model chosen, significant reform is needed at the Reserve Bank. Some of that is about organisational structure and governance – I’ve made the case for a standalone new Prudential Regulatory Agency – but much of it is about organisational culture, and that sort of change is harder to achieve. I hope Adrian Orr has the mandate, and the desire, to bring about such change. I hope Grant Robertson insists on it.

Readers will that early last year, Steven Joyce – as Minister of Finance – had Treasury employ a consultant to review aspects of the governance of the Reserve Bank, particularly around monetary policy. Extracting details of the review, undertaken by Iain Rennie, from The Treasury proved very difficult. It took almost a year for the report to be released. I’ve had various Official Information Act requests in, including for the file notes taken from the (rather limited) group of people outside The Treasury that Iain Rennie engaged with (within New Zealand it turns out that he talked to no one outside the public sector). That one ended up with the Ombudsman. A week or so ago I finally got an offer via the Ombudsman’s office – Treasury would release a document summarising those meetings if I discontinued my request for the full file notes. Somewhat reluctantly – balancing the point of principle, against getting something now – I agreed, and last Friday Treasury released that summary to me. For anyone interested it is here.

Rennie review Summary of discussions with External Stakeholders

There is some interesting material there, including on meetings with the Reserve Bank Board – where he showed no sign of having grilled the Board on what it accomplishes or adds – and with some overseas people Rennie talked to. But what caught my eye was the record of a meeting Rennie (and Treasury) held with the Reserve Bank management (Wheeler, Spencer, McDermott and a couple of others) on 14 March last year. At the meeting, the Bank seems to have set out to minimise any change and sell Rennie on the virtues of the current informal advisory Governing Committee.

Here are relevant bits of the record (as summarised now by Treasury)

Current Governing Committee (GC)

o The GC reflects public sector reforms, there are checks and balances, which help with accountability.

o It has become important to focus more on the Reserve Bank as an institution, rather than just on the Governor, as the Reserve Bank has taken on more and more responsibilities over time.

o Discussed different overseas models, including strengths and weaknesses of different approaches.

o The approach to decision-making and communications needed to be consistent with the Reserve Bank’s approach (e.g. must be appropriate in the context of forward guidance).

Codification of the Committee Structure

o Codification’s advantage was that it could prevent a future Governor from moving back to a single decision-maker. However, that hasn’t been a problem in Canada, and it would be difficult for a Governor to roll the current committee approach back.

Effectiveness

o The cohesion of the GC and the cooperative nature were identified as the most important factors in its success. The GC was relatively informal with collective responsibility, and that worked well.

o Discussed how the current committee operated, and some strengths and weaknesses of the approach.

o Discussed the effectiveness of different options for decision-making and communications design, such as voting and minutes (neither supported).

Some of this is almost laughable, a try-on that surely they should not have expected anyone to take very seriously (and, to Rennie’s credit, he came out with recommendations that went far further than the Bank liked, earning him soe quite critical comment from the Bank).

Take that very first bullet, the claim that the Governing Committee model “reflects public sector reforms”. I’m not sure how. It has no basis in statute, the members are all appointed by and accountable to the Governor, and there is no transparency, and no accountability. The Bank has, for example, consistently refused to release any minutes of the Governing Committee – on any topic – if indeed, substantive minutes are even kept.

Or the fourth bullet, the suggestion that “the approach to decision-making and communications needed to be consistent with the Reserve Bank’s approach”, which is a typical bureaucrat’s attempt to reverse the proper order of things. The Reserve Bank is a powerful public agency, created by Parliament and publically accountable (well, in principle). The design of the governance and accountability arrangements should reflect the interests and imperatives of the principal (public and Parliament), not those of the agent (the Bank itself). Officials work within the constraints Parliament establishes.

Or the third to last bullet, about the cohesion of the Governing Committee, collective responsibility etc. Again, I’m sure they believed it, but on the one hand, we build public institutions to provide resilience in bad times (or bad people) not so much for good times, and on the other there is no collective responsibility – the Governor alone has legal responsibility, and there is no documentation at all on the Governing Committee processes. And legislating to entrench a committee in which the Governor appoints all the members, might be a recipe for cohesion, but it is also a high risk of a lack of challenge, debate and serious scrutiny.

And, finally, just to confirm that consistent opposition to anything approaching serious scrutiny, in that final bullet, the Bank reaffirms its opposition to published minutes – something most of central banks now manage to live with, in some cases with considerable detail.

At one level, these comments no longer matter much. Graeme Wheeler and Grant Spencer have moved on, and the new government has made decisisions on the future governance of monetary policy. But they nonetheless highlight the sort of closed culture fostered at the Reserve Bank over the past decade or more, whether on the monetary policy side or on the regulatory side (the latter vividly illustrated in the NZI report). Comprehensive reform is overdue. It would make for a better Reserve Bank internally – and/or a better Prudential Regulatory Agency – and one more consistently open to scrutiny, challenge, and debate, which in turn will reinforce the impetus towards better policy, better analysis, and better communications.

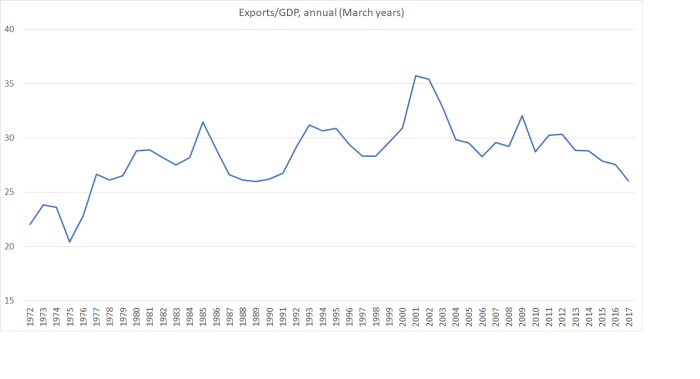

The past 15 years have been pretty dreadful, and the last time the export share of the economy was less than it was in the March 2017 year was the year to March 1976 – back in the days when (a) export prices had plummeted, and (b) the economy was ensnared in import protection, artifically reducing both exports and imports (our openness to the world more generally).

The past 15 years have been pretty dreadful, and the last time the export share of the economy was less than it was in the March 2017 year was the year to March 1976 – back in the days when (a) export prices had plummeted, and (b) the economy was ensnared in import protection, artifically reducing both exports and imports (our openness to the world more generally).