When I mentioned to my wife this morning that I’d been reading a fascinating post about 700 years of real interest rate data her response was that that was the single most nerdy thing I’d said in the 20 years we’ve known each other (and that there had been quite a lot of competition). Personally, I probably give higher “nerd” marks to the day she actually asked for an explanation of how interest rate swaps worked.

The post in question was on the Bank of England’s staff blog Bank Underground, written by a visiting Harvard historian, and drawing on a staff working paper the same author has written on bond bull markets and subsequent reversals. It looks interesting, although I haven’t yet read it.

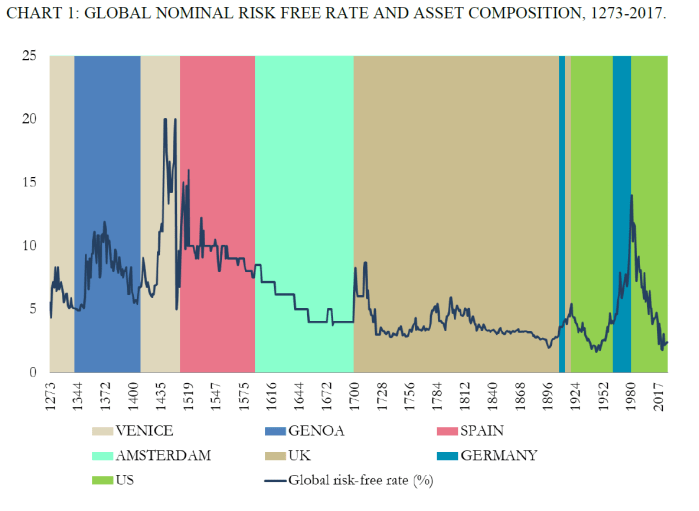

Here is the nominal bond rate series Schmelzing constructed back to 1311.

And with a bit more effort, and no doubt some heroic assumptions at times, it leads to this real rate series.

Loosely speaking, on this measure, the trend decline has been underway for 450 years or so. It rather puts the 1980s (high real global rates) in some sort of context.

In the blog post the series is described this way

We trace the use of the dominant risk-free [emphasis added] asset over time, starting with sovereign rates in the Italian city states in the 14th and 15th centuries, later switching to long-term rates in Spain, followed by the Province of Holland, since 1703 the UK, subsequently Germany, and finally the US.

In the working paper itself, “risk-free” (rather more correctly) appears in quote marks. In fact, what he has done is construct a series of government bonds rates from the markets that were the leading financial centres of their days. That might be a sensible base to work from in comparing returns on different assets – perhaps constructing historical CAPM estimates – but if US and West German government debt has been largely considered free of default risk in the last few decades, that certainly wasn’t true of many of the issuers in earlier centuries. Spain accounts for a fair chunk of the series – most of the 16th century – but a recent academic book (very readable) bears the title Lending to the borrower from hell: Debt, taxes, and default in the age of Philip II. Philip defaulted four times ‘yet he never lost access to capital markets and could borrow again within a year or two of each default’. Risk was, and presumably is, priced. Philip was hardly the only sovereign borrower to default. Or – which should matter more to the pricing of risk – to pose a risk of default.

In just the last 100 years, Germany (by hyperinflation), the United Kingdom (on its war loans) and the United States (abrograting the gold convertibility clauses in bonds) have all in effect defaulted – the three most recent countries in the chart. Perhaps one thing that is different about the last 30 or 40 years is the default has become beyond the conception of lenders. Perhaps prolonged periods of peace – or minor conflicts – help produce that sort of confidence, well-founded or not.

I’m not suggesting that real interest rates haven’t fallen. They clearly have. But very very long-term levels comparisons of the sort in the charts above might well be concealing as much as they are revealing. They certainly don’t capture – say – a centuries-long decline in productivity growth (productivity growth really only picked up from the 19th century) or changing demographics (again, rapid population growth was mostly a 19th and 20th century thing). And interest rates meant something quite different in an economy where (for example) house mortgages weren’t pervasive – or even enforceable – than they do today.

As for New Zealand, at the turn of the 20th century our government long-term bonds (30 years) were yielding about 3.5 per cent, in an era when there was no expected inflation. Yesterday, according to the Reserve Bank, the longest maturity government bond (an inflation-indexed one) was yielding a real return of 2.13 per cent per annum. Real governments yields have certainly fallen over that 100+ year period, but at the turn of the 20th century New Zealand was one of the most indebted countries on the planet whereas these days we bask in the warm glow of some of the stronger government accounts anywhere. Adjusted for changes in credit risk it is a bit surprising how small the compression in real New Zealand yields has been.

per BOE post: “….never before has a longer period without deflation existed than the ongoing 70-year spell since World War Two” – should or could this change? thought it somewhat interesting given the theme of low real rates and missing global inflation.

LikeLike

it could change – especially if we get a new severe recession and haven’t fixed the near-zero lower bound issue. but also worth recalling that it is the only 70 year period in history of reliance everywhere on fiat money.

LikeLike

“Governments throughout history have needed to borrow money to fight wars. Traditionally they dealt with a small group of rich financiers such as Jakob Fugger and Nathan Rothschild but no particular distinction was made between debt incurred in war or peace. An early use of the term “war bond” was for the $11 million raised by the US Congress in an Act of 14 March 1812, to fund the War of 1812, but this was not aimed at the general public. Until July 2015, perhaps the oldest bonds still outstanding as a result of war were the British Consols, some of which were the result of the refinancing of incurring debts during the Napoleonic Wars, but these were redeemed following the passing of the Finance Act 2015.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_bond

I think fiat money or issuing debt bonds has a much longer history than the last 70 years.

LikeLike

Prior to the 1990s the price of land was calculated as part of the inflation index. This lead to higher interest rates as a result of rising land prices affecting inflation. Subsequently as land prices was removed from the inflation index there is now no real pressure on inflation with the resultant lower interest rates.

LikeLike