Earlier this week various media outlets were carrying reports of a new speech on immigration from Green Party co-leader James Shaw. In both Stuff and the Herald, articles were headed “Green Party apologises for anti-immigration pandering. To be fair to Shaw, that wasn’t quite what he said.

A year or so ago, the Greens came out with a new policy on immigration. The aim was to produce annual population growth of around 1 per cent, and they would adjust immigration policy settings (in light of changes in rates of natural increase or of the comings and goings of New Zealanders) to meet such a target. At the time they talked a lot about the pressure points that really big net migration inflows caused. Shaw told Radio New Zealand

“We know that immigration is becoming more of a concern for people and in my experience the vast majority of people aren’t concerned about immigrants, they’re concerned about the impact on house prices, and infrastructure.”

They seemed mostly to be about stabilising population growth pressures, rather than reducing average net immigration very much at all. After all, average annual population growth in New Zealand in the 20 years prior to the current immigration surge was 1.1 per cent, and rates of natural increase are slowing.

But whatever their intentions, I think everyone who thought about the issue at all seriously, concluded that their policy was unworkable, mostly because of the big – and not readily forecastable – fluctuations in the comings and goings of New Zealanders. I wrote about it at the time

In a sense the fatal conceit in the Greens new policy is the idea that New Zealand’s population growth rate can be held stable from year to year. While New Zealanders are fairly free to move – or not – to the much larger Australian economy in response to changes in relative economic opportunities – and while New Zealand incomes are so much lower than those in Australia – we will almost inevitably have the sorts of swings in the net outflow of citizens I showed in the first chart above. Trying to manage the inflow of non-New Zealanders year by year to offset those fluctuations would be (a) impossible, and (b) something of a fool’s errand even to try.

Others pro-immigration people have made the some point about the unworkability of the scheme.

So in that respect it is good that the specific formulation of a target has been dropped. If they were serious about a population policy – and I think they are the only party to have one – they could have rephrased it to aim to produce average population growth of around 1 per cent per annum on, saying, a five year forward looking basis. That would have been less unworkable. But, instead, the numerical target has gone altogether.

From the tone and content of Shaw’s latest speech there must have been a huge backlash in some quarters against the party leadership, and probably Shaw in particular, over last year’s proposed policy.

Last year I made an attempt to try and shift the terms of the debate away from the rhetoric and more towards a more evidence-based approach.

We commissioned some research which indicated that immigration settings would be best if tied to population growth.

Unfortunately, by talking about data and numbers, rather than about values, I made things worse.

Because the background terms of the debate are now so dominated by anti-immigrant rhetoric, when I dived into numbers and data, a lot of people interpreted that as pandering to the rhetoric, rather than trying to elevate the debate and pull it in a different direction.

We were mortified by that

I guess I’m not a Green supporter, but much of this just looks unrecognisable. Go back and look at the mainstream media coverage, and no one then seemed to think he was “pandering”. It looked at the time like a serious attempt (apparently backed by some commissioned research) to grapple with some pressing issues – especially around housing and transport – and if the solution he came up with wasn’t very workable (and probably should have had a lot more internal stress-testing before it was released for public consumption), it was a serious attempt. It didn’t blame migrants for New Zealand policy failures, it simply recognised that very rapid population growth can create stresses for us all. As Shaw noted then

Mr Shaw said the aim of the policy was for better planning, and less hostility towards immigrants.

“The debate around immigration is kind of being captured by those voices who are just simply anti-immigrant, and we really want to make sure that doesn’t happen.

It all seemed pretty calm and rational (even if unworkable). In fact, at the time so calm and rational that Shaw could even use the (relatively) moderate “anti-immigrant” to describe those who wanted to pull back more significantly on immigration.

There is none of that calm moderation in this week’s speech. In a speech of only 1350 words, “xenophobia” appears four times, and “scapegoating” three times (admittedly “racism” gets in only once). People who disagree with the Greens’ stance are, apparently, characterised by such evils. And on the other hand, the Greens are the party of love

I’m proud to lead a party that stands for the politics of love and inclusion, not hate and fear

and

Openness, inclusiveness and tolerance must win out over racism and scapegoating and xenophobia. Love and inclusion must win out over hate and fear.

If that isn’t pandering, I’m not sure what is. And all the while attempting to secure the high moral ground. Thus

We in the Greens are deeply concerned that the debate about immigration policy in New Zealand has, over the course of time, come to be dominated by populist politicians preaching a xenophobic message in order to gain political advantage.

This ugly strain of political discourse is quieter at times of low net migration into New Zealand, but rises at times of when net migration is high – as it is now, and so, at this election, sadly, the xenophobic drum is beating louder.

“Xenophobia” is one of the favoured words of the groups – whether from the right or the left – in our society who favour a continuation of our unusually large-scale immigration policies.

My Oxford dictionary defines xenophobia as a “morbid dread or dislike of foreigners”. I’d challenge Mr Shaw, or others in the media and lobby groups who like to the fling around the word – or cognates like “fear” (widely used in this year’s New Zealand Initiative report) – as if the only basis for questioning New Zealand’s immigration policy can be something irrational, to produce some evidence for their claims. I presume Shaw isn’t wanting to apply this description (“xenophobia”) to his Labour Party allies who recently came out with some proposals designed to reduce the net inflow of migrants (at least temporarily), using much the same sort of arguments Shaw himself was articulating, calmly and reasonably, only last year. No doubt he intend his comments to apply to Winston Peters – also the avowed target of the New Zealand Initiative’s report. I’m no fan of Peters, but I’ve read various of his speeches over the years, and listened to him in interviews, and the “morbid dread of foreigners” seems to bear no relationship at all to what Peters is saying. Do the Greens recognise any legitimate reasons for being sceptical about the merits of the large scale non-citizen immigration programmes New Zealand runs?

“Scapegoating” is one of Shaw’s other favourite words. Here, there was a section in Shaw’s speech that I totally agreed with

Migrants are not to blame for the social and economic ills of this country.

Migrants are not to blame for the housing crisis.

Migrants are not to blame for our children who go to school hungry.

Migrants are not to blame for the long hospital waitlists.

Migrants are not to blame for our degraded rivers.

It is the government’s failure

But again, is anyone engaged in the public debate saying anything different? I was flattered to be described recently by the New Zealand Initiative as “New Zealand’s most articulate critic of immigration”. I’ve said repeatedly that migrants are just doing what all of us probably seek to do – pursuing the best opportunities for ourselves and our children. The problem isn’t the individuals, it is the policy choices governments make. Again, is anyone who is critical of current immigration policy saying anything different?

Shaw seems to have abandoned what he described as

an attempt to try and shift the terms of the debate away from the rhetoric and more towards a more evidence-based approach.

and tried to cover his own poor specific policy proposal last year, by adopting instead the politics of the slur. And all while pretending to claim the high moral ground. Perhaps naively, I’d always thought the Greens – much as I disagree with them on most things – were better than that.

As it is, we are now left unclear what the Green Party’s immigration policy really amounts to. To their credit, there is a 10 page densely-typed immigration policy document on their website, but neither it nor the two page summary give us much clarity at all.

They begin

We support an appropriate and sustainable flow of migrants

Which differentiates them from who how? “Appropriate” is one of those words bureaucrats use when they don’t want to be specific.

And among their three ‘key principles’

Maintain a sustainable net immigration flow to limit effects on our environment, society and culture.

Surely any possible worries about the impact on “society” or “culture” could only stem from “xenophobia”? Or is that only when other people make such arguments?

There are strange observations such as

Only make decisions to use immigration as an instrument of economic policy openly by an Act of Parliament

I don’t really disagree, but…..immigration policy operates under the Immigration Act, passed and amended by Parliament. And among the purposes listed in that Act is

contributing to the New Zealand workforce through facilitating access to skills and labour

The Immigration Act, at least in its modern guises, has always been substantially an instrument of economic policy.

There is lots of detail on various aspects of the policy, but no sense at all as to how many permanent non-citizen migrants we should be seeking to take each year. We know they are keen to take more refugees, but it isn’t even clear whether that increased intake would be in addition to the total number of non-citizens we take in each year at present, or whether additional refugees would replace some others.

On voluntary migrants they say

an open immigration policy would be unmanageable, and it is the Government’s duty to ensure that voluntary immigration is managed in the national interest. Although ‘national interest’ can mean different things to different people, the definition that has informed our national immigration policy for many years is that we should accept people who will bring skills, capital, or other desirable attributes with them.

And they have a view on the types of skills which should be favoured

Give priority in the skilled migrant category to skills needed for a sustainable society and economy, such as scientists, engineers and other trades with specialised skills applicable to fields including — but not limited to — organic farming, biodegradable materials, recycling, and renewable energy and fuels.

But there is nothing, at all, as to whether current target levels (around 45000 per annum residence approvals) is too high, too low, or about right.

Not even their general stance towards the environment gives much clue. In discussing “yearly immigration quotas” they say we need

an assessment of the ability of our environment to cope with population increases, taking into account changes in energy use and other behavioural and infrastructural factors;

but they also talk in the same breath of

the need to have spare environmental, social and cultural ecological capacity to accommodate potential returning New Zealanders and people displaced by climate change

But what does it all mean? You could mount a good argument, on environmental grounds, for a much lower annual target for new residents. And the likely economic costs of meeting our climate change emissions commitments – made more difficult by rapid increases in population – would just reinforce that, especially as the Greens are explicit that immigration policy needs to be managed for the interests of New Zealand, not the world. But that doesn’t seem to be the Greens approach at all.

And then of course, there are the cultural dimensions. Here is what they have to say

The Taonga of our people, and sites of historical, cultural, environmental, recreational, and general emotional significance for resident New Zealanders, should be protected from adverse impact as a result of immigration, and should not be seen as up for sale to wealthy newcomers. The Green Party will:

1. Take all reasonable steps to prevent immigration numbers, and the sale of land to rich immigrants, from having an adverse impact on Taonga.

But, again, what does it mean? And why isn’t it what the Greens themselves would refer to as “xenophobia” if anyone else was raising the issues?

Perhaps one can only conclude that answering fairly basic questions like how many non-citizens we should take in each year, or even just what rationing devices we should use to decide which migrants to take, is altogether too hard. That isn’t promising for a party that wants to be in government only a few months hence.

Reading Shaw’s speech the other day, I did notice this line

in fact, the Greens have the ambition of being the most migrant-friendly party in Parliament.

I did carefully note the potential distinction between “migrant-friendly” and “migration-friendly”, but when I first read the line I was struck by how similar it was to lines one sometimes sees from ACT. David Seymour obviously thought so too, as he was soon out with a release casting doubt on the Greens’ claims in this area, and suggesting that ACT really was the most pro-immigration party. Perhaps the Greens just want to be known as nice, while Seymour explicitly eschews niceness

We stand up for productive immigrants and the businesses that employ them, not because it feels nice, but because New Zealand needs immigrants

In fact, I suspect both parties have quite strong globalist leanings – more so than a concern for the interests of existing New Zealanders – but neither can quite bring themselves to consistently adopt such an approach. Curiously, both also seem keen on values statement and the indoctrination of immigrants – even if they probably couldn’t agree much about what ideas they’d indoctrinate the immigrants with.

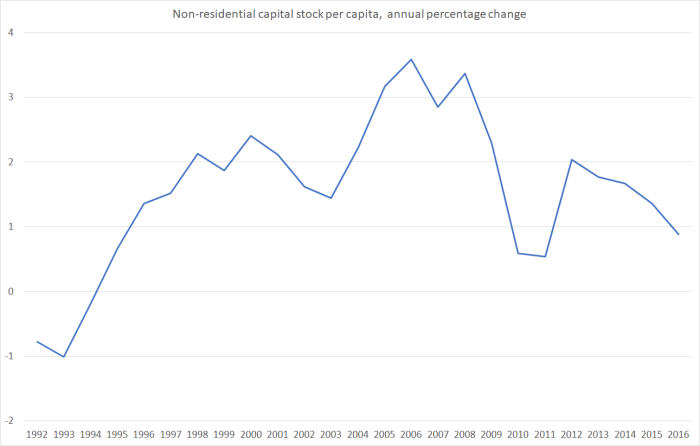

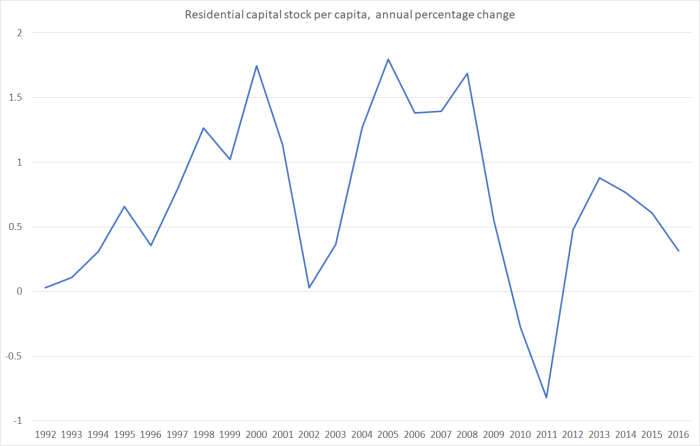

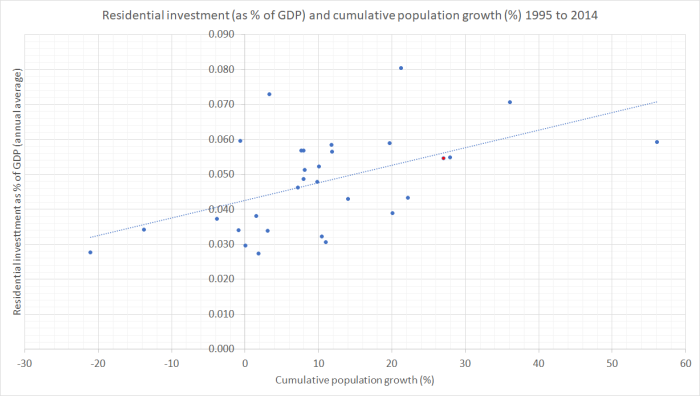

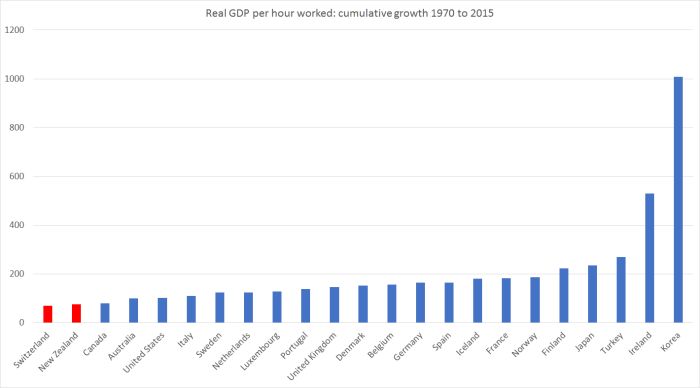

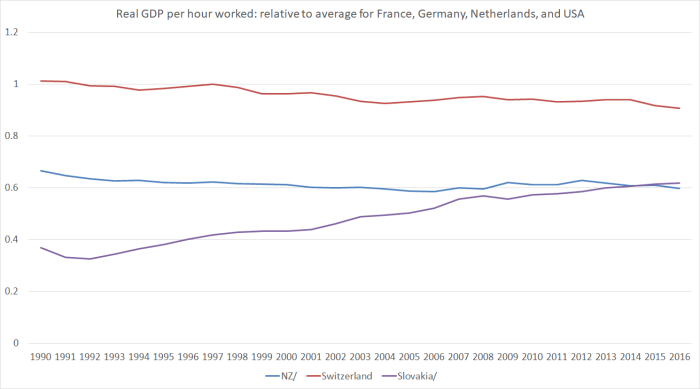

If it weren’t for such leanings, it is hard to imagine the Greens – vocal champions of clean rivers etc – wouldn’t be much more strongly advancing an agenda that avoided government policy exacerbating population pressures on the environment. Whether on economic grounds, or environmental grounds, the immigration programme we’ve run for at least the last 25 years (through all sorts of year to year swings in the overall net inflow or outflow) simply doesn’t look to have been working in the interests of New Zealanders as a whole. If the Greens disagree, it would be good to see the argumentation and evidence.