I’m still under the weather with the after effects of a bad cold, so this won’t be a long post.

Treausry has long been a champion of New Zealand’s large scale non-citizen immigration programme, going all the way back to when the system was opened up in the earlier 1990s. But more recently, there have signs of some differences of view even within the organisation. in 2014, they published (consultant) Julie Fry’s working paper on migration and macroeconomic performance in New Zealand, which was a pretty sceptical, but careful, assessment of whether there had been any material gains to New Zealanders. Fry’s conclusion was that any gains had been “modest”. There was, I gather, quite a difference of view within the organisation as to whether the paper should even be published.

Treasury has also been on record as having some concerns about possible adverse labour market outcomes for lower-skilled New Zealanders from, for example, the big increase in the number of working holiday schemes New Zealand has signed up to. They noted, in a presentation released last year,

Our key judgment is that migrant labour is increasingly likely to be a substitute for local low -skill labour, and this is an impact that we should try and mitigate.

But they have remain upbeat about the potential contribution from genuinely highly-skilled immigrants.

And at the top of the organisation, the public view on New Zealand’s immigration from the Secretary to the Treasury, in a succession of speeches and interviews, has been relentlessly positive – and equally relentlessly devoid of evidence.

In the Treasury’s Long-Term Fiscal Statement released late last year they were apparently torn between creedal statements, and a grudging engagement with the evidence, notably a recognition that “we are not seeing the agglomeration effects we would expect from Auckland’s size and scale”.

So I was interested to see that in the Budget Economic and Fiscal Update last week, Treasury looked at a scenario in which the overall net migration inflows stay even larger for longer than Treasury’s central projection. As it is, their central projection numbers are already high: after growth in working age population of 2.4 per cent in the year to June 2016, they expect to have seen growth of 2.7 per cent in the year to this June, and 2.4 and 2.1 per cent increases for the next two years.

The scenario is as follows

This scenario illustrates the impact of higher migration on the economic and fiscal outlook when capacity constraints arise. In this scenario, net migration is assumed to remain around its current level of 70,000 per annum through to the end of the forecast period.

The results include

In this scenario, stronger population growth drives faster growth in household consumption, residential investment and business investment. Stronger domestic demand is reflected in faster employment growth. However, in the construction sector, it becomes increasingly difficult to access labour and materials. As a consequence, there is additional upward price pressure on construction costs, which leads to higher headline inflation. The policy interest rate rises earlier and the exchange rate is higher as monetary policy seeks to stabilise inflation.

So far, so conventional in many ways. This is the standard experience in New Zealand when there are large migration inflows. There is nothing here of the lines the Reserve Bank has been running for the last year or so, in which increased net migration somehow eases overall inflation pressures.

But what really caught my eye was the next sentence

Reflecting these conditions, growth in labour productivity, real wages and real GDP per capita is more moderate than in the main forecast.

They didn’t need to include that observation at all. The scenario would have made perfect sense without it. But here is the government’s premier economic advisory telling them – and us – that if net migration remains at current levels it would be expected to have detrimental effects on productivity (and wages). I wonder what the Secretary to the Treasury makes of that?

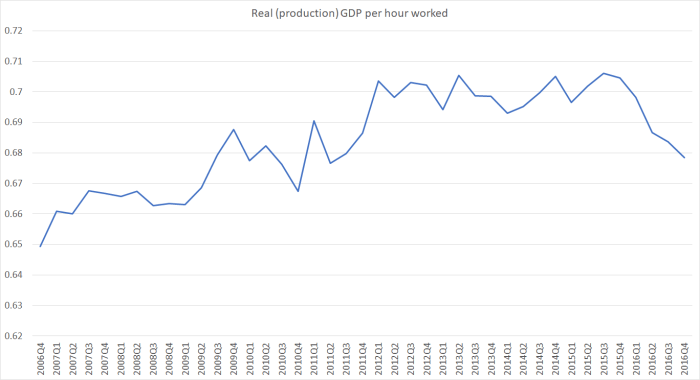

After all, it is not as if there has been much productivity growth for the last few years. Treasury uses a measure of GDP per hour worked that simply uses production GDP (I usually use an average of the two GDP measures in charts here). Here is what their measure looks like.

No growth in labour productivity at all for the last five years (the last year’s drop is largely just a series break in the HLFS hours worked, consequent on survey question changes).

Perhaps coincidentally, that happens to have been the period over which we’ve had big increases in, and persistent very high levels of, net PLT migration (much of it a reduction in the annual outflow of New Zealanders). And, as I noted, the other day, on Treasury’s own estimates, there have been no economywide capacity constraints at play in that period – the output gap is estimated to have been (and still to be) negative. For enthusiasts for large scale migration, it should have been a good time for seeing lots of productivity growth.

For some reason, in their central forecasts Treasury expects quite an increase in productivity growth from about now. They never explain what (about the economy or policy) is changing that will end now the run of five years of zero productivity growth. These are their central forecasts (on page 6 here) for labour productivity growth.

| Forecast annual growth in labour productivity,

June years |

|

| 2018 | 1.3 |

| 2019 | 1.9 |

| 2020 | 1.1 |

| 2021 | 1.1 |

Perhaps as puzzling, are their real wage forecasts. Even though Treasury expects the unemployment rate to fall, and the rate of productivity growth to accelerate, these are the real wage growth forecasts.

| Forecast annual growth in real wages, June years | |

| 2017 (est) | 0.0 |

| 2018 | 0.7 |

| 2019 | 0.6 |

| 2020 | 0.0 |

| 2021 | 0.0 |

Five years and a forecast growth in total real wages of only 1.3 per cent. It is enough to make one glad not to be in the paid workforce. Workers will surely be hoping that Treasury’s alternative immigration scenario – with those adverse productivity and real wage effects they talked about – don’t come to pass. (And I am a little surprised that no Opposition party seems to have pointed out how bleak the outlook for workers’ incomes is under the central Treasury forecasts.)

It would be interesting to have an updated honest and considered assessment from Treasury as to what our immigration policy is doing for New Zealanders. I suspect there is still a tension between the textbooks and the “ideology”, and the growing accumulation of reasons to doubt that, in these remote islands, in an age when personal connections matter more than ever, simply piling up more people here – many of the newcomers not even being that highly-skilled – is making us better off, not worse off. It is a strategy that is great for owners of business in the non-tradables sectors – more people means more demand – but not for the economy as a whole. Our living standards depend heavily on the ability of firms here to find ever more ways of successfully selling stuff to the rest of the world. That simply hasn’t been happening on anything like the necessary scale, and the absence of aggregate productivity growth is just one reflection of that.

70,000+ more people from immigration, 28 billion of new debt/credit money mainlined into the arteries of the economy and no real increase in the median income and a near non existent increase in GDP per capita to show for it. Our biggest city an unfolding nightmare of congestion, pollution and housing in crisis. You would think treasury would be desperate to find out what the hell has gone wrong.

Interesting that Bill English came out the other day with a complete reversal and said what has been obvious for some time – essentially that wages are being held down by immigration and that it is difficult to reconcile claims that there are worker shortages when weak wages indicate nothing of the sort.

“I see more and more businesses who understand, it’s a bit of a departure from the traditional kiwi model that they need to invest in a supply chain, a supply line, of qualified skilled people.

“For some of them that means… going to the local secondary school, so people know your industry is there. For some of them it means understanding the migration system. For some of them it means investing more in your own people…

“Finally sometimes, you’ve got to pay more.”

http://www.interest.co.nz/business/87959/prime-minister-bill-english-admits-wage-growth-isnt-hot-says-businesses-need-increase

LikeLiked by 2 people

yes, I was interested in those English comments. Then again, he was doubling down on the big NZ strategy in this article

https://www.nbr.co.nz/article/alternative-infrastructure-financing-talks-making-headway-says-english-b-203543

“We believe New Zealand can adjust to be a growing economy with a growing population,” he said. “Our political opponents think New Zealand isn’t up to it, it’s too hard and the solution is to shut down the growth by closing off international investment, getting out of international trade, closing down migration and settling for a kind of grey, low-growth mediocrity where the best thinking of the early (19)80s sets our political direction.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, well they have to look like they have got some sort of a plan I guess but they are really talking about playing catch up for the population growth that has already occurred. No plan to raise exports, productivity, wages and the general well being of the people; weren’t we supposed to be well on the way to equal Aussie incomes by now?

LikeLike

Thank you for another clear post and good luck at shaking off your cold.

Today’s Herald has an opinion piece by Michael Barnett of head of Auckland chamber of commerce that actually contains some reservations about our current immigration policy. It made me think who is benefiting from excessive immigration? Well it has had the unintended effect of doubled my wealth by my accidentally owning Auckland property. And of course it gives us your articles which make learning economics a pleasure. The obvious winners will be most of the members of Auckland Chamber of Commerce running businesses that are thriving by simple growth in customers. So when even they have reservations the situation surely calls for a change of direction in our Immigration policy.

I’d be interested in what you make of this quote from his article: “.. sectors like tourism, meat and dairy where non-NZ control of supply chains is impacting on the sector’s performance.” I would have assumed that overseas control might occasionally lead to grabbing profits over long term investment but surely it makes little difference if say a cheese factory is owned by foreigners or say a Kiwisaver fund or a NZ businessman?

LikeLike

Still scratching the head. Lower productivity should mean lower real rates with the ‘excess demand’ described above showing up within inflation rather than real rates: hence, the NZD should, in theory, be moving lower. Or, perhaps NZ is more productive than the numbers can evidence which is why the foreign capital keeps flowing (or I guess it could be the land / scenery combo that is in scarce supply elsewhere…)

LikeLike

This subject keeps going around in circles without really touching the sides … as one reads the pleadings of the domestic homeless, domestic car-dwellers, domestic-garage-dwellers, native renters who are would-be home-buyers and establishers of household-units and the bleatings of those living on the urban outskirts who cant afford to travel to a low-paying shelf-stacking job on the other side of the city

I contemplate the immigration flood that is evident in Auckland and I keep thinking of the elites who tell us we need overseas capital and overseas people with high skills to broaden our society without ever telling us how or ever presenting factual evidence from 20 years of hordes of imports blowing in

I keep thinking of this analogy

A peaceful desert island in the middle of the Pacific with a single stand of coconut trees on which are two young educated university post-doctoral graduates, one male, one female, living a tranquil lifestyle. There is no industry. There are no businesses. Just fishing and coconuts and themselves

Then one day, out of the blue an ocean-going yacht arrives, onboard is a Nuclear Physicist who likes the look of the place and decides to stay

That blow-in suddenly increases the theoretical skill level by 33%, but in practice probably reduces the pre-existing labour output below 100% by creating dis-harmony among the now group of 3

The moral of the story is what new industries have been created by 20 years of inbound migration and what has caused the deficits of infrastructure and why are the locals being starved of healthcare and the bottom-dwellers are being forced out onto the streets when New Zealand is humming along, GDP is growing and everything is rosy – feel the success – why – tell me

LikeLiked by 2 people

Mitchell Pham first arrived in New Zealand from Vietnam at the age of 13.

He is the co-founder, director, international development director and GM of business development of the Augen Software Group, a company with offices both in New Zealand and in Vietnam.

With 20 years of history Augen Software have very aggressive growth strategies in NZ. For the Innovation sector, continue to extend our reach around the country, to provide innovating companies with our insourcing model for agile development resources and scalability,” explains Pham. “For the community health/disability/social services sector, we continue to advance our Benecura web app and Mobicura mobile apps, to support the sector to innovate, develop and succeed in the delivery of positive outcomes.”

He is also a member of the Strategic Alliance Vietnamese Ventures International (SAVVi) network, and a member of the executive committee of the global Vietnamese diaspora business network (BAOOV).

https://www.reseller.co.nz/article/471982/from_refugee_entrepreneur/

LikeLike

Vietnam will be the initial market and a base to launch into other Southeast Asian markets. Pham sees it as a big opportunity for New Zealand to get on Asia’s business radar.

“New Zealand isn’t as relevant in Asia as we could be, yet we’ve got so much to offer. If we want to [succeed] there, we’ve got to be more present and more engaged.”

Last year Augen established a partnership with a construction and engineering group in the Vietnamese electricity industry to deliver solar and wind energy solutions to the Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos markets. They were joined by an Indonesian group this year.

Augen has shored up a partnership with a New Zealand “green desktop management” software company and aims to take that solution to the Asia-Pacific region.

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=10719252

LikeLike

Auckland – The Kiwi Connection Tech Hub is working with NZ businesses, industry and government across multiple initiatives to support 100 Kiwi entrepreneurs, managers and executives to visit major South East Asia markets this year to increase exports.

Hub director Mitchell Pham is working with organisers of the significant landmark business trip to Vietnam, Thailand and possibly Myanmar in a giant leap forward to boost New Zealand exports In partnership with Augen. The New Zealand mission to South East Asia will focus on businesses in various tech, food and beverages and retail sectors.

“The trail-blazing visit in August will be led by ASEAN-New Zealand Business Council in collaboration with ExportNZ, KEA and the Kiwi Connection Tech Hub and with support from NZTE, MFAT and the Asia New Zealand Foundation.

“In addition to that trip, at the same time, the University of Auckland Business School has 65 management and executive participants in this year’s MBA programme helping 11 Kiwi businesses develop market entry strategies, execution plans and local connections for the Vietnam market. This group will also be working in-market in August Trade mission to Singapore and Vietnam.

https://www.mscnewswire.co.nz/news-sectors/out-of-the-beehive/item/4269-kiwi-entrepreneurs-to-cash-in-on-seasian-markets.html

LikeLike

Of course given the number of immigrants there will be successes. But I think you imply if he had been a typical NZ 13 year old he would have had less drive for success. This could be true. Then he has his heritage that would make getting and keeping Vietnamese business contacts much easier. And for a minority language like Vietnamese this would also be true. There is a slight advantage in having an alien background – Hitler, Stalin and Napoleon they were all foreigners – when it results in a focused mind and a willingness to chose your own path. On the other hand they may be more likely to have less allegiance to NZ; a successful software business can move anywhere.

What puzzles me in NZ is the lack of export businesses created by immigrants of Indian origin. In Britain Indian companies employ over 1million UK workers and there are many are self-made millionaires. In NZ we seem to have Indians running dairies and more recently petrol stations but almost none are involved in the investor category for immigrants. Maybe an Indian will read and answer.

LikeLike

Not about 13 year olds and how well a migrant does. The point is that migrants and international students have an enduring relationship with NZ. These are our business contacts of the future and these are people that may not stay in NZ or may travel frequently back to their home countries but by spending many years in NZ they acquire a taste for NZ food products and NZ technology which they would spread around the world. They are also our future business partners and form friendship bonds that last a lifetime.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Five years and a forecast growth in total real wages of only 1.3 per cent.”. If that was well known and believed then the government will change at the next election.

LikeLike

Looks like it is down to the wire and Winston Peters as the Kingmaker. Winston will not want to deal with the Greens especially with the new young guns of Cloe Swasbrick and lawyer Golriz Ghahraman who are very vocal. Guess my prediction is another National led government with Winston Peters as the Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister.

LikeLike

All options are frightening. I see your point about foreign students at our real universities but whether they return home with +ve feelings for NZ will depend on how they are treated. The current influx of low standard barely skilled foreign workers may be causing resentments among working class Kiwis which in turn could make life as a young foreign student in Auckland less than happy.

LikeLike