My post yesterday about the Prime Minister’s immigration interview at the weekend prompted a few comments from people keen to pin the responsibility for the current policy on John Key and offering thoughts on what electoral motives National might have for favouring high rates of non-citizen immigration.

Now, of course, any incumbent government (especially one that has held office for more than seven years) must accept some responsibility for current policies. Especially on matters that don’t require legislation, if they didn’t like the current policy, they could have changed it.

But, as I’ve pointed out on various occasions, current policy is not some bold new innovation of the current government. It is, more or less, a continuation of the policies of previous governments since at least the start of the 1990s. A couple of weeks ago, I linked to the 2014 immigration policies of the various smaller parties, not one of which suggested any material disquiet with the regime. (I didn’t link to the 2014 Labour policy, and they now appear to have taken down their 2014 policies, but here is a 2014 summary of the various party immigration policies. Labour seemed then to favour more use of immigration policy in a counter-cyclical way, but there is no obvious disquiet with the overall target levels.)

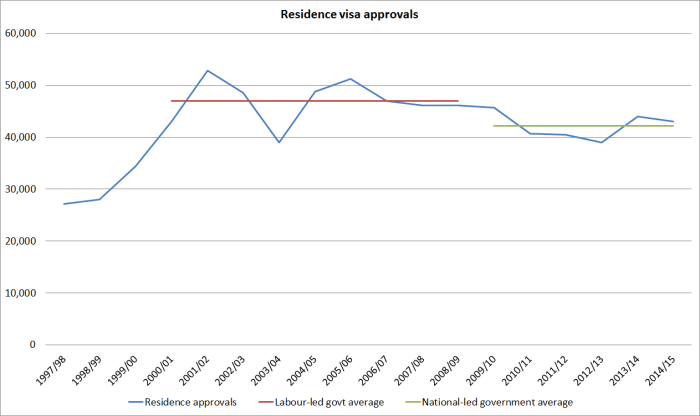

And what of the practice? The MBIE website has a series for residence approvals for each year back to 1997/98. Here is a chart of that data, including averages for the previous Labour-led governments (2000/01 to 2008/09) and the current National-led governments (2009/10 to 2014/15).

The target number of approvals (45000 to 50000 per annum) has not changed from one government to the other, and the average number of residence approvals has actually been slightly lower under the current government than it was under the previous government (probably largely reflecting the fact that labour market conditions have been more difficult in recent years). As the population is now 20 per cent larger than it was in 2000, annual residence approvals as a share of the existing population are now quite a bit lower than they were back then (albeit still very high by international standards – roughly three times, per capita, legal immigration to the United States).

There have been plenty of refinements of policies over time – some for the better, others not. We’ve had changes in the eligibility for parent visas, changes in the points offered for people moving to places other than Auckland, and an increased orientation in granting entry to people with specific job offers (an approach criticized – I think rightly – in the new Fry and Glass book). But the overall approach to residence approvals has had much more continuity than difference from one government to the next. And only people who get a residence visa can stay here permanently.

What of some of the other visa types? Foreign students are a reasonably significant export market, and if there has been some (material) change in policy over the granting work rights to longer-term students while they are here, overall student visa numbers haven’t changed much from one government to the other.

Ideally, one might have hoped that we’d be seeing more students than 10-15 years ago, but mediocre universities and a high exchange rate are obstacles to that.

The number of working holiday scheme visas granted has increased hugely.

But (a) if you didn’t know the dates of the change of government, you couldn’t tell from the chart, and (b) much of the more recent expansion of working holiday programmes seems to have been in pursuit of votes for the Security Council seat, a goal shared and pursued by both main parties. Moreover, although 60000 visas were granted last year, these people are typically only in New Zealand for a few months. I don’t have any strong views on working holiday schemes, although in papers released last year, even Treasury expressed some unease.

The number of people granted work visas has also trended up very strongly – most strongly when the unemployment was very low – over the period since 1997/98.

But again, there is no obvious difference between the experiences under National and Labour led governments. Much of the trend reflects the change of approach under which most people who obtain residence visas do so from within New Zealand. In the 1990s, most people who got residence visas did so directly from abroad, but now the most common model is for someone to come on a work (or student) visas, get established in a specific job here, and then apply for a residence visa. That aids the integration of the people who do come but, as Fry and Glass note, may not help attract the very best people.

The point of this post so far has been to illustrate the substantial continuity, and commonality of approach, from one government to the next.

But on the off chance that anyone thinks ‘but Winston is different’, recall that Winston Peters was Deputy Prime Minister and Treasurer in the National-New Zealand First government from 1996 to 1998, and was Foreign Minister in the Labour-led government of 2005 to 2008.

I tracked down a copy of the (very long) 1996 coalition agreement between National and New Zealand First. Immigration policy is dealt with on page 45. Here is what it said:

Statement of General Direction:

The goal is to have an immigration policy that reflects New Zealand’s needs in terms of skills, ability of the community to absorb in relation to infrastructure and recognising the diversity of the current New Zealand population. Such a policy will take into account the capacity of this nation to meet the general economic and social needs of New Zealanders.Key Initiatives of Policy:

To maintain current immigration flows as per the last quarter of 1996 until the Population Conference has been held in May 1997.

- Introduce a strict four year probationary period.

- Introduce a limited overstayer amnesty following agreement upon appropriate definition and objectives of the amnesty

- Health screening of overseas visitors.

- Population Conference/strategy.

- Clamp down on refugee scams.

- Increased resources to policing immigration policies

Whatever you make of the specifics, it doesn’t have the ring of something dramatically different from what had gone before (or what came after). (And for those of a historical bent, here is the programme – with comments from the then Prime Minister and the then Minister of Immigration – for that Population Conference.)

By 2005, confidence and supply agreements were rather shorter, but this is what the Labour-New Zealand First agreement said about immigration

Immigration

• Conduct a full review of immigration legislation and administrative practices within the immigration service, to ensure the system meets the needs of New Zealand in the 21st century and has appropriate mechanisms for ensuring the system is not susceptible to fraud or other abuse, and taking note of other items raised by New Zealand First.

Again, not suggesting any very material changes of policy.

Of course, minority parties have to prioritise. My point is only that over 25 years in practice our high levels of inward non-citizen migration have been the result of a widely-shared consensus among our political parties (and bureaucrats). Some might have been zealous for it, and others just not that bothered. Perhaps that outcome has been a good thing, leading to real economic gains, or perhaps not (it would nice if the advocates could show us the evidence of those gains), but it certainly isn’t a Key innovation.