I was exploring joining the Reserve Bank in late 1982, and as the then Deputy Chief Economist was walking me round the floor he commented that one of the attractions of the Reserve Bank was getting involved in all sorts of housing issues. It struck me at the time as slightly odd. I don’t recall housing coming up as an issue in the previous years of macro-oriented university study.

But, sure enough, housing issues came up a lot in the course of my time at the Bank. Rapid housing credit growth in the years after the share market crash (we concluded that it couldn’t go on for long), the mid 1990s housing boom and Don Brash’s hankering for “tweaky tools”, the treatment of housing in the CPI (and in early Policy Targets Agreements), the Supplementary Stabilisation Instruments Report, the Mortgage Interest Levy, more work on possible alternative instruments including tax options, arguments about appropriate risk weights for housing, connections (or the absence of them) between house price booms and savings, reviewing OECD reports on this, that, and the other dimensions of housing, 2025 Taskforce reports, “macro-prudential” policy frameworks, and most recently – and terminal to my relationship with Graeme Wheeler – the LVR speed limit.

This was never intended to be, and won’t be, a housing blog. When I left the Bank a couple of weeks ago, I’d put together a large pile of items I wanted to write about – some of which will interest many, and others few – and so far I’ve got to only few of those topics.

But housing has become the topic of the week. An anonymous commenter yesterday suggested that:

The tone of the blog suggests you have an emotional attachment to not wanting housing to be considered over valued, subject or likely to unwind, and resistant to anything to curb further inflation. Sounds venal. Own a few investment properties – or just one of those people who becomes emotionally invested into an issue and starts becoming irrational?

I don’t own, and have never owned, an investment property. As it happens, Welllington looks like one of those places where investment properties would not have offered a very attractive return in the last decade. I grew up mostly in “tied cottages” (my father became a Baptist minister when I was young) and I’ve owned two houses, in succession, in the same seaside suburb. I hope that the executors of my estate (several decades hence I hope) will do the next property transaction.

But if I have an emotional investment in this issue at all, it is to be scandalised at the way in which a succession of no doubt well-intentioned political choices have been pushing home ownership beyond the reach of a growing number of young and middle-aged New Zealanders. Good intentions do not excuse bad outcomes.

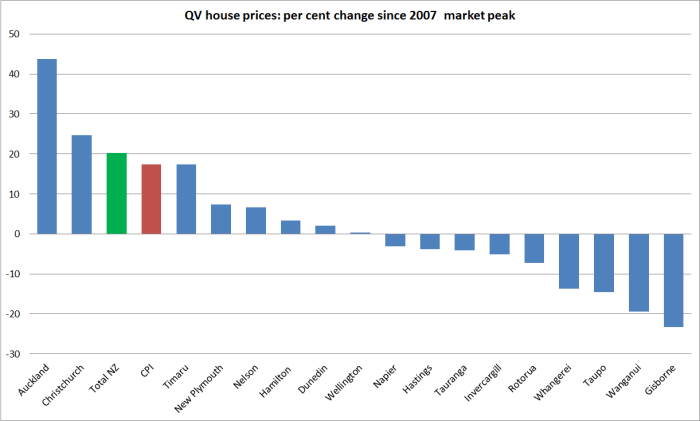

It is not that accommodation itself is beyond the reach of those people. One of the striking features of the last 10-15 years is that rents have not increased that much. Partly as a result, the cost of consumption (the private consumption deflator) has increased much less than the CPI. I also don’t have an instrumental view of home ownership – that we should promote it because it is good for societal cohesion or any number of worthy outcomes that are often argued. I don’t think home ownership should be promoted at all, as a matter of public policy – and, while I wouldn’t push the case, I would have no principled objection to a tax on imputed rentals, provided that the costs of home ownership, including the interest cost of the debt finance component, were deductible.

But we should not stand in the way of home ownership, by adopting policies which put high hurdles in the face of young people getting into purchasing a house, if that is what they want to do. And nor should we be settling for the diminished ambitions I heard in a discussion on National Radio yesterday – two panellists talking of how perhaps we should all get used to living in small apartments, and well, really, well-designed apartments could be surprisingly spacious. Perhaps they do if they want to live in the inner-city, with all the other amenity value than can offer to some people. But there is no reason why it should be the norm. Most people still want the backyard, where the kids can kick a ball.

If New Zealand isn’t one of the most successful advanced economies, we are a rich and fairly prosperous country, with real incomes well above those 50 or 100 years ago. Housing is a normal good: when we get richer we generally want more of it, not less, and in a country with lots of land per capita, there is no obvious reason why we can’t have more of it. My parents were like many of their generation: they bought a first house in the early 1960s in the then outer suburbs of Christchurch. It was new, and quite small. As people did, they landscaped it themselves over time. And they serviced it on one income. Incomes today are much higher than they were then. But despite the higher income, land prices would put that beyond reach of the typical young family today.

No doubt some planning restrictions are an efficient coordination device (thoroughgoing libertarians might disagree). I have no particular problem with the idea that new factories shouldn’t be allowed to set up in residential areas. Perhaps too there is a case for some basic government building standards for houses – though we and our children live in our houses (and take any risks), not central or local government officials. And, yes, new housing does involve infrastructure requirements, and we need good models for ensuring that the costs of that infrastructure are borne (upfront or over time) by those who create the additional demand. But when land and building costs have got so high – and ownership of a basic family home has got beyond so many – surely it is time for an urgent rethink.

Good dairy land sells for perhaps $50000 per hectare. I just googled Upper Hutt sections – not exactly central Wellington, let alone Auckland – and it looks as though one would pay $250000 there for not much more than 500 square metres of a residential section. The two aren’t the same – services, streets etc cost money – but the gap between the two should be a reproach to our politicians. The 2025 Taskforce some years ago suggested that councils should have to publish regular reports documenting the cost of land in their area, explicitly comparing land zoned residential with otherwise similar land not zoned for residential purposes. Information helps change things, and this still looks like a modestly useful recommendation to me. Better still might be some sort of statutory presumption that landowners can build houses (perhaps to three floors high) on any land (not, for example, seriously geologically unstable). It isn’t the full answer, but we need to shift the presumption towards the rights of landowners (and the interests of potential purchasers/residents) rather than agendas of central or local government officials and politicians.

Land use restrictions are much less binding in communities/countries in which there is little population growth. I’m sceptical of New Zealand’s immigration policy for other reasons, but if we are going to target large inflows of non-citizens, and we know that a large proportion will end up in our largest city (which is what happens with migrants around the world), we owe it to our own people to ensure that they aren’t inadvertent victims of this policy choice. Again, good intentions don’t excuse bad outcomes. New Zealand governments should make policy for New Zealanders: we should allow/promote non-citizen migration to the extent that it benefits New Zealanders. There is no necessary conflict between rapid population growth and affordable urban house prices – cities such as Houston have illustrated the point. But if, for whatever reasons, the New Zealand political process can’t or won’t make urban land supply much more responsive, we need to think much harder about medium-term target levels of non –citizen inflows. Trying to combine rapid population growth and fairly tight land use restrictions comes at great cost to younger generations of poorer (and often browner) Aucklanders (in particular). That is simply unjust.

Perhaps because I don’t know when to stop I want to comment briefly on foreign ownership restrictions on residential property. My general starting point is that foreign investment should be welcomed, and that New Zealanders should be free to sell their houses (or farms, or businesses) to pretty much whomever they prefer. And when someone migrates to New Zealand of course they should be free to buy a house. But Auckland (in particular) is now a hugely distorted market, and the policy priority has to be minimising the damage those policies are doing to ordinary New Zealanders (and approved residents). Auckland houses (and land) shouldn’t be particularly scarce, but government choices have made them so.

I haven’t seen convincing evidence that there is yet much purchasing of Auckland (or New Zealand more generally) residential property by non-resident foreigners, but it would not surprise me if it were gradually becoming more of an issue. We know that there is a lot of private capital flowing out of China, and jurisdictions with secure property rights will look attractive. If there were evidence of significant non-resident buying in New Zealand, I would somewhat reluctantly support tax or regulatory restrictions. Yes, doing so restricts the sales opportunities of New Zealanders, but that scarcity value (in the land price) has only arisen from the supply restrictions interacting with government choices about population/immigration pressures. There was no good economic case for the supply restrictions in the first place. So the lost opportunity to sell this artificially scarce asset is not something that should unduly trouble New Zealand policymakers.

I haven’t touched much here on the tax treatment of housing. My views were pretty much summed up in various earlier Reserve Bank documents (eg here or here). There is no perfect tax system, and no doubt the tax treatment of housing isn’t ideal or fully “neutral”. But the key features of the tax system have been in place for a long time, and if anything have become less supportive of housing in the last decade or so. They cannot credibly explain the transition from affordable to severely unaffordable urban land and house purchases.

So , finally, do I have an emotional attachment to some of these issues? Of course. These things matter. Good intentions have produced shocking outcomes, and that really needs to change. House and land prices should come down, in real terms. But there isn’t anything obviously irrational about house prices as they are – they look a lot like the rational outcome of a badly chosen combination of policies. And who knows when, or if, they will change.