That is the title of a new New Zealand Initiative report out yesterday, with the subtitle “How misunderstanding the past jeopardises our future”.

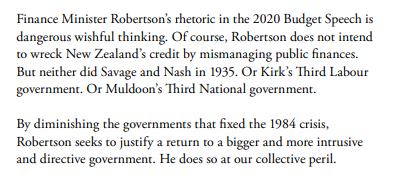

I’m no fan of this government, including its economic policies, and often lament how little New Zealand economic history is taught (none at all for example in our capital city university), so I should have been favourably predisposed towards such a report, which appears to have been prompted (specifically) by a couple of recent quotes from the Minister of Finance. This is how the report starts

And here is how it ends

You’ll get the drift.

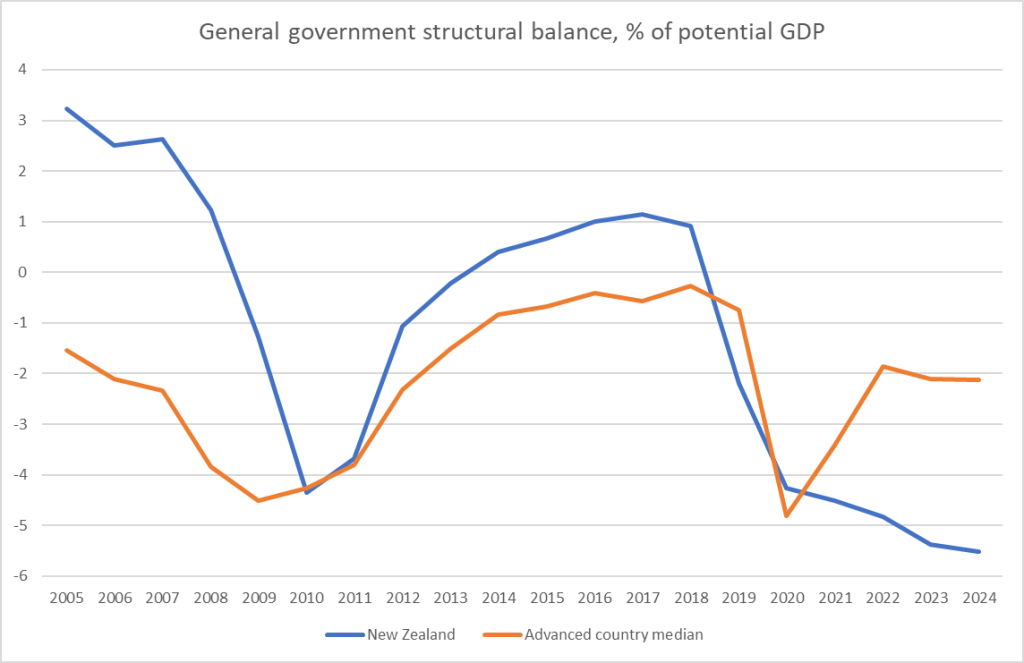

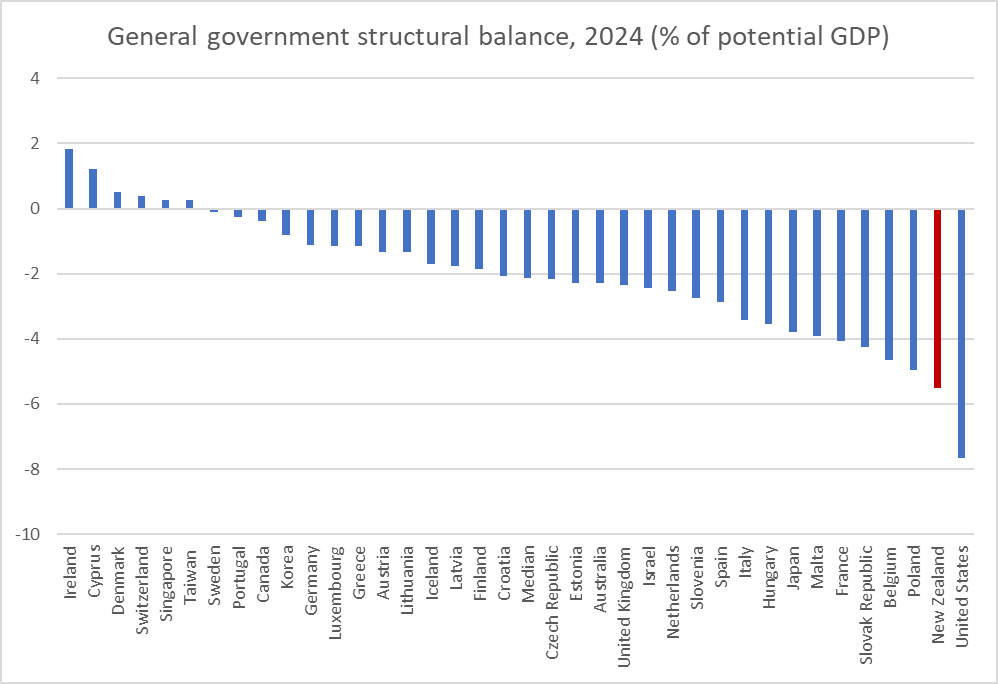

I’m very sympathetic to the story that both Robertson and his boss are keen on a “bigger and more intrusive and directive government”, and it is clear that they have no serious ideas about (and demonstrate little interest in) reversing the decades of relative productivity decline. Most likely, their approach will see New Zealand outcomes worsen relative to those in the rest of the world. I’ve also been quite critical of this year’s Budget and the huge cyclically-adjusted deficits the government was choosing to run at a time when their forecasts suggested the economy was running at pretty much full capacity.

And yet, and yet.

There seem to be two themes or driving concerns to the report. The first is to re-present aspects of New Zealand’s economic (policy) history in ways less sympathetic to Grant Robertson’s rhetoric, and the second is alarm – I would probably call it alarmism – about the current and prospective global situation. On that latter, these paragraphs also come from the last couple of pages of the report.

I’m probably not much more keen on big debt and big deficits than the report’s author – Bryce Wilkinson – is, but this sort of broad-brush rhetoric seems set to discredit useful and important points that could be made, especially in the New Zealand context.

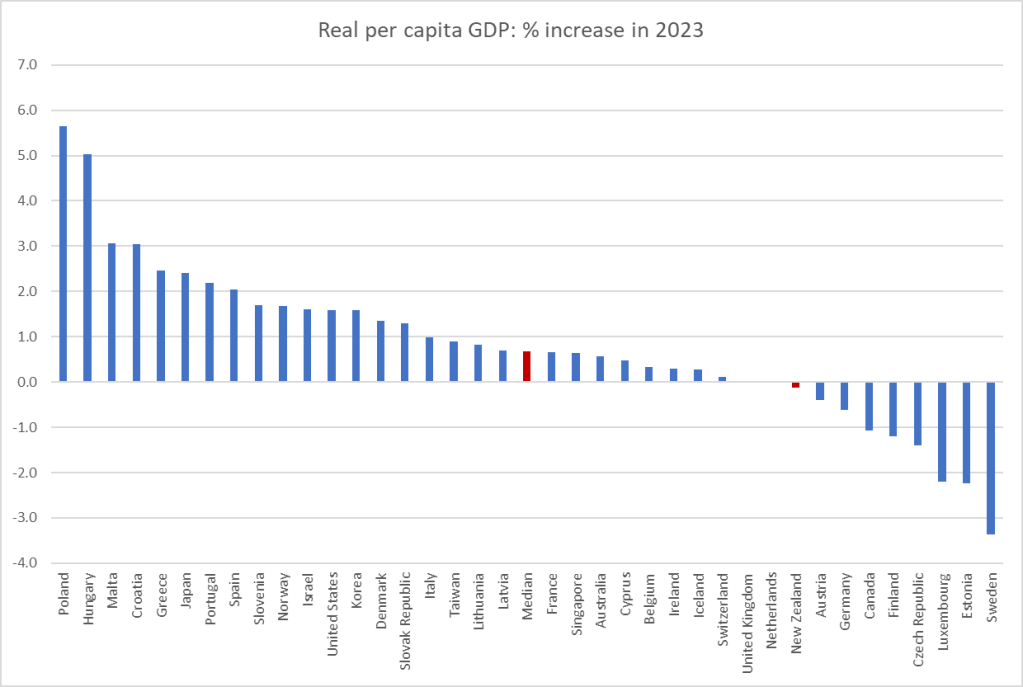

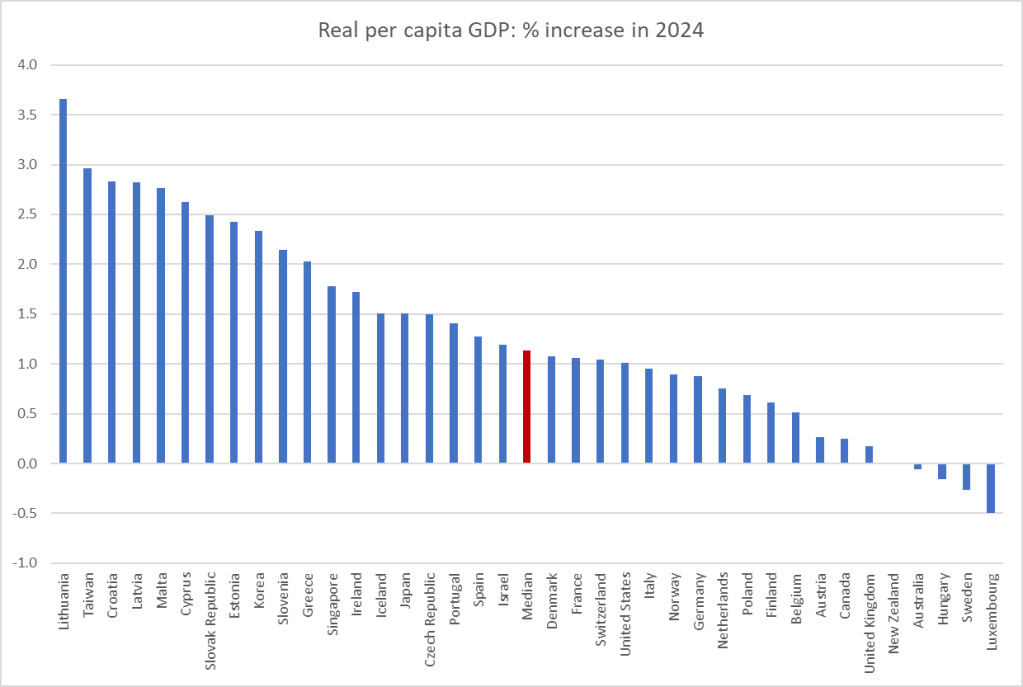

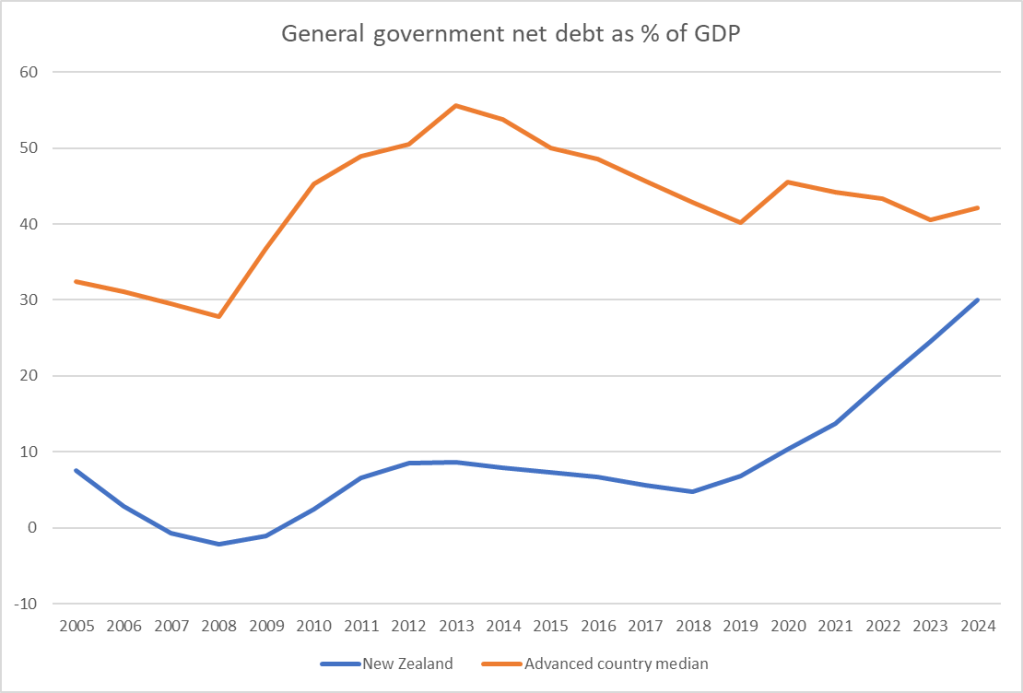

Are there “unresolved fiscal problems that followed the 2008 global financial crisis”? Most probably there are, in some countries anyway, although even in the United States – exemplar of chaotic fiscal policy surely – the problems were evident before 2008, were worsened again by the Trump tax package, and are now being worsened again by what the Democrats are now trying to push through. It is a sorry picture – and the US is still a consequential country – but it isn’t the New Zealand story. We ran into big deficits for a time after 2008 – some mix of a late spend-up by the previous government, poor macro forecasts, the recession itself, and the earthquakes – but we pulled ourselves out of that hole, with (in the main) bipartisan support for doing so. On the OECD’s net general government financial liabilities measure (the broadest and most internationally comparable) we were at zero net debt just prior to Covid (and almost a quarter of OECD countries had positive net general government financial assets).

As Bryce acknowledges, the New Zealand government’s own fiscal projections have debt stablising and then slowly falling as a per cent of GDP. And if the level the socialists are happy to see it stabilise at might be higher than either Bryce or I would prefer…it is hard to get very excited about that level. Whichever measure you prefer, on none of them is there any risk of New Zealand running into a public debt crisis. Of the government’s range of debt indicators, I like the net debt one that includes NZSF assets: Treasury see that being 25 per cent of GDP in 2025.

And what about “monetary excesses”? Well, I’m not fan of QE-type programmes, but mostly because they make little sustained macroeconomic difference, but provide central banks some feeling of “doing something”. And perhaps the world really is about to see a sustained break-out of inflation, but……nowhere in the advanced world, not even in the US, are financial markets (with money at stake) suggesting that is the most likely outcome. Our own central bank, having presided over 10 years of undershooting the inflation target, was actually on the brink of tightening just last month, and may yet do so next month. At the moment, markets think governments will allow central banks to (and central banks will act to) keep any sustained lift in core inflation pressures in check. Markets may be wrong – it has been known – but I’m not sure our Minister of Finance has a strong ground for thinking they are.

And what about the history, the central part of the report’s title?

There is a rather weird reverence in some circles for the first Labour government, at least the period under M J Savage in the late 1930s. Labour seem particularly prone to it, which I suppose is somewhat understandable, but it even infects the other side of politics at times (In this post I unpicked some Todd Muller rhetoric on similar lines, during his brief stint as Leader of the Opposition). It seems to be sentimental rather than rigorous, and the NZ Initiative report is a useful quick canter (albeit with a historical error or two) through material on the macroeconomic mess that Labour government ran us into by 1938/39. At a macro level, we were simply saved by the war, but then lived with the panoply of microeconomic restrictions and controls in one form or another for the next 45 years. But it is rather light on some significant differences from the present: not only was the New Zealand government very highly indebted in the late 1930s (well over 100 per cent of GDP, not primarily the fault of the Labour government), but we were also running a system of fixed exchange rates. And we did not have a monetary policy run consistent with the demands of the exchange rate system

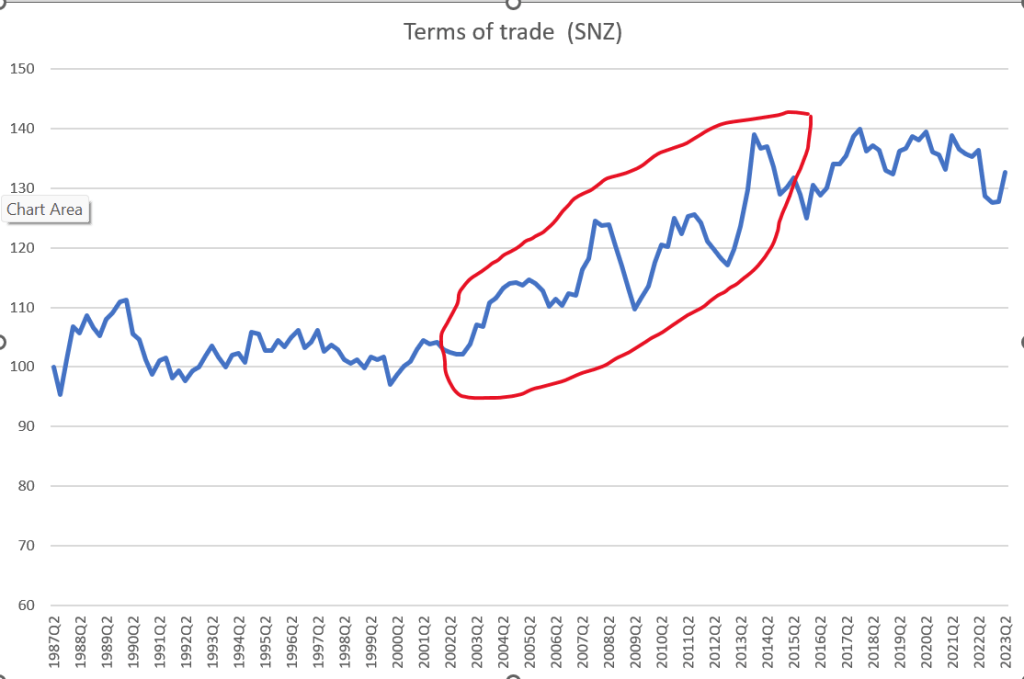

There is more (also with some arguable interpretations/emphases) on the macroeconomic mess New Zealand was in by 1984. That mess can be overstated – partly because inflation itself overstated the severity of (notably) fiscal deficits – but the truth was messy enough. But it wasn’t primarily a fiscal crisis – there was no question of default, no question of lenders being unwilling to lend to us – but a productivity underperformance one and (in the immediate) a monetary policy crisis. We had a fixed exchange rate regime, and we did not have a monetary policy run consistent with the demands of the exchange rate system.

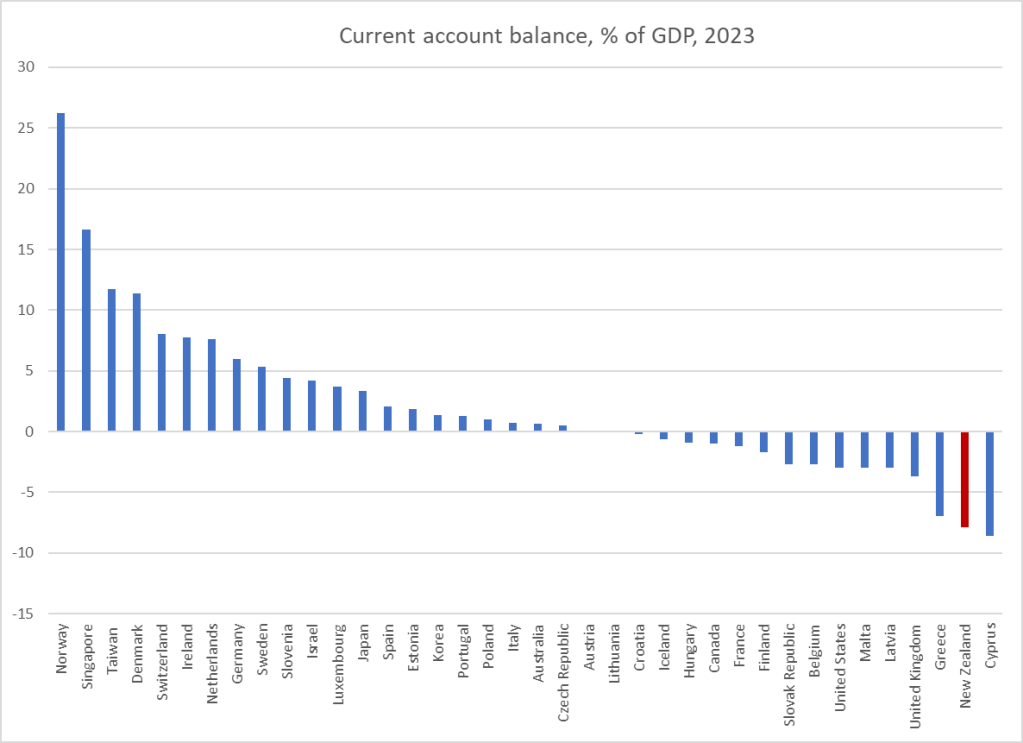

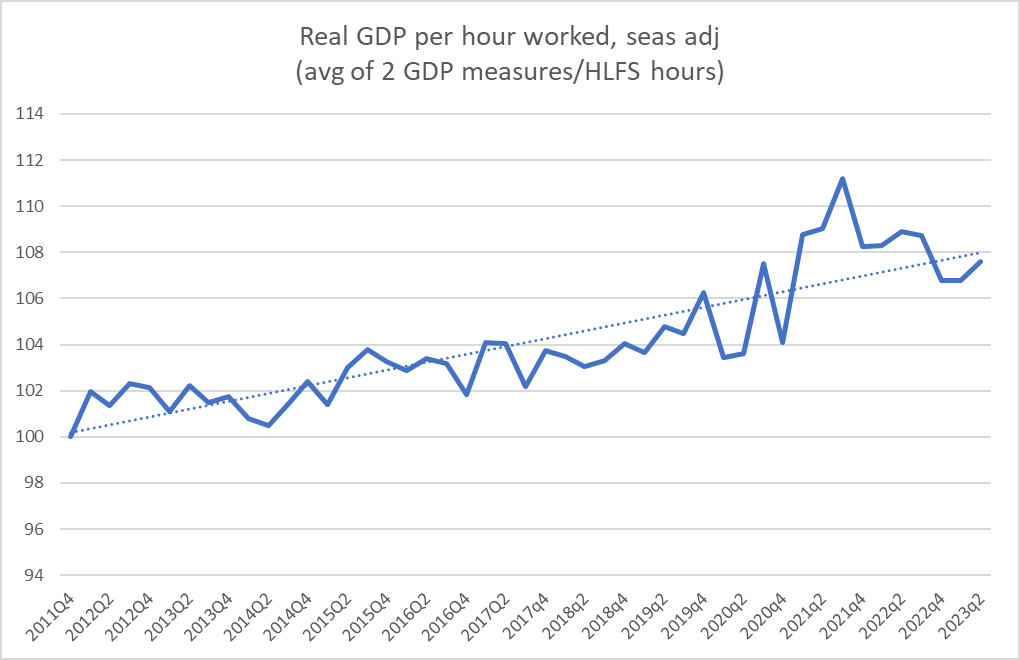

By contrast, at present we have a long-running woeful productivity performance – basically the enduring theme of New Zealand economic history at least since World War Two – but we know (including because we experienced it for the last 25 years) that that isn’t inconsistent with macroeconomic stability.

We have large fiscal deficits for this year and next (on the Treasury’s best interpretation of government policy as communicated to them) but public debt ratios that are low by any standards (cross country or historical) at a time when servicing costs, while not as low as in some countries, are very low by historical standards. The effective duration of the government’s debt portfolio is shorter than desirable – and the LSAP programme is responsible for that – but crisis material it isn’t (and it wouldn’t be even if we had another bad earthquake in the next few years).

And, we do have a central bank that – for all its many weaknesses (mostly the key people) – still operates, by law (and it seems in practice) at arms-length from the government, and (for all its florid rhetoric about other stuff) shows every sign of easing policy when core inflation falls away and tightening policy when core inflation looks like rising. And which has a target, set by the government, that is totally conventional internationally. And if nothing else, having a monetary policy that runs that way – consistent with our exchange rate regime and with the inflation target – makes things utterly different, in macroeconomic stability terms, than in 1938/39 or in 1984.

Having said that, I suspect the real thing that drove the report was the opportunity to litigate Grant Robertson’s take on the 4th Labour government. Personally I tend to take that sort of Robertson rhetoric with a considerable pinch of salt, since a great deal of his style seems to involve the appearance of product differentation from the 4th Labour government even when the substance barely changes (the Reserve Bank Act amendments are a classic examples). Feelings around the late 1980s are clearly still raw, especially in the Labour Party, and it seems to be good politics to pander to that.

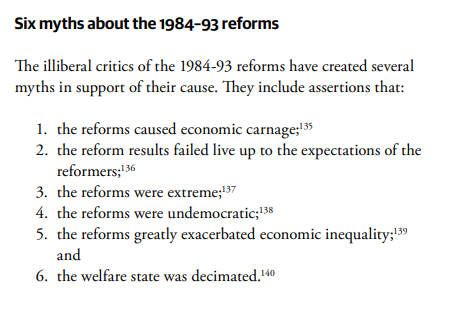

But Bryce Wilkinson frames six “myths” about the 1984-93 reforms. He summarises them thus

Personally, I think the truth is probably somewhere in the middle. Take for example, the first one. The Robertson quote emphasises the damage to communities, and even Wilkinson in the report acknowledges the pain of the reforms for many. He might argue it was unavoidable by then, and Robertson would have been better not to have talked about “economic carnage” (especially when the basic economic model now isn’t that different).

Were the reforms “extreme”? I don’t think so, but they were unusually far-reaching, and in places went where few other countries had yet gone. For better or worse (I think mostly better) they positioned us very well in many international policy/institutional comparisons by the 1990s having started well behind. And I recall the time we spent in one OECD review of New Zealand urging them to take out language (which they intended as a compliment) suggesting that our reforms were unusually ambitious.

Were the reforms “undemocratic”? At one level, clearly note. They were undertaken by democratically-elected governments. But Wilkinson’s specific rebuttals risk inviting derision. He suggests that the snap election “gave no time” to Labour to articulate its ideas…..which more or less concedes the platform was never campaigned on. I have a bit more sympathy for the 1987 re-election argument, except…..that Labour’s manifesto that election, with talk of further significant reforms, was published after the election. And the 1990-93 Bolger government story was also a mixed bag – labour market reform was a significant part of their campaign but (for example) benefit cuts were not, let alone the amped-up superannuation surcharge. Call it democratic or undemocratic as you like, perhaps even call it unavoidable, but it wasn’t very transparent ex ante.

Call my overly literal, but “decimated” probably roughly accurately describes the welfare system effect – it was still there and, rightly or wrongly, just quite a bit less generous than it had been before.

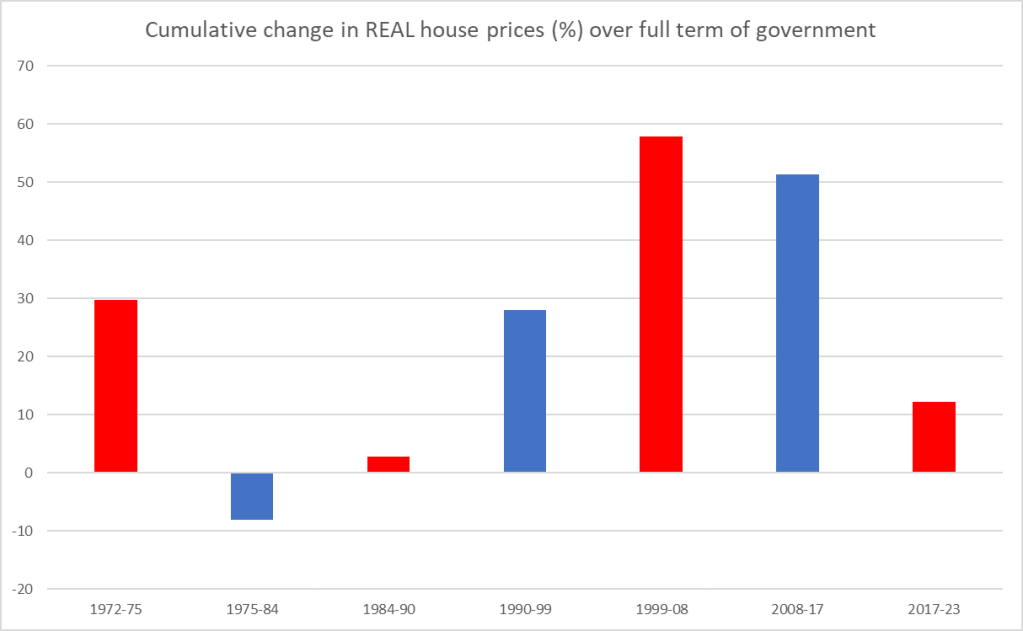

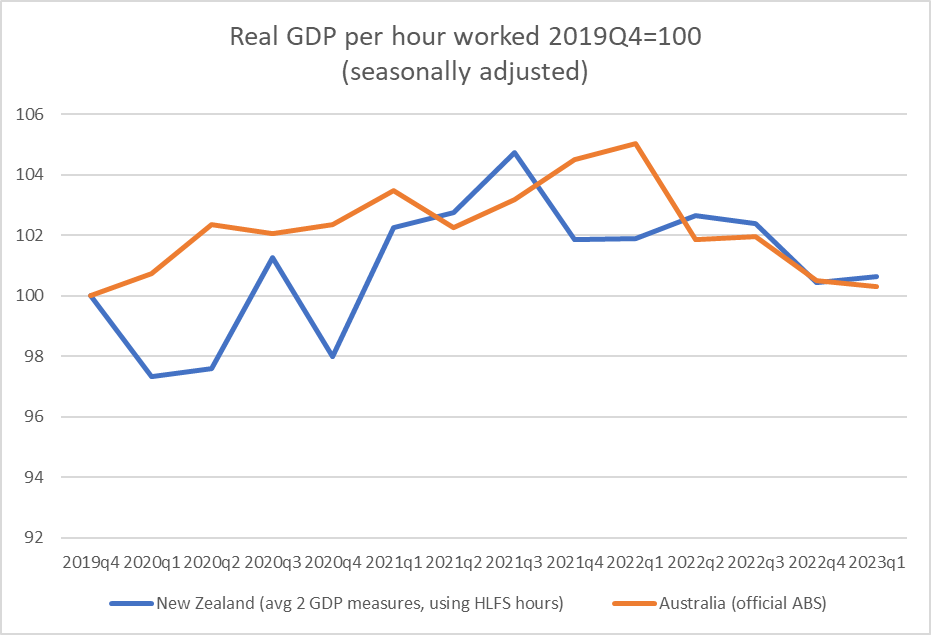

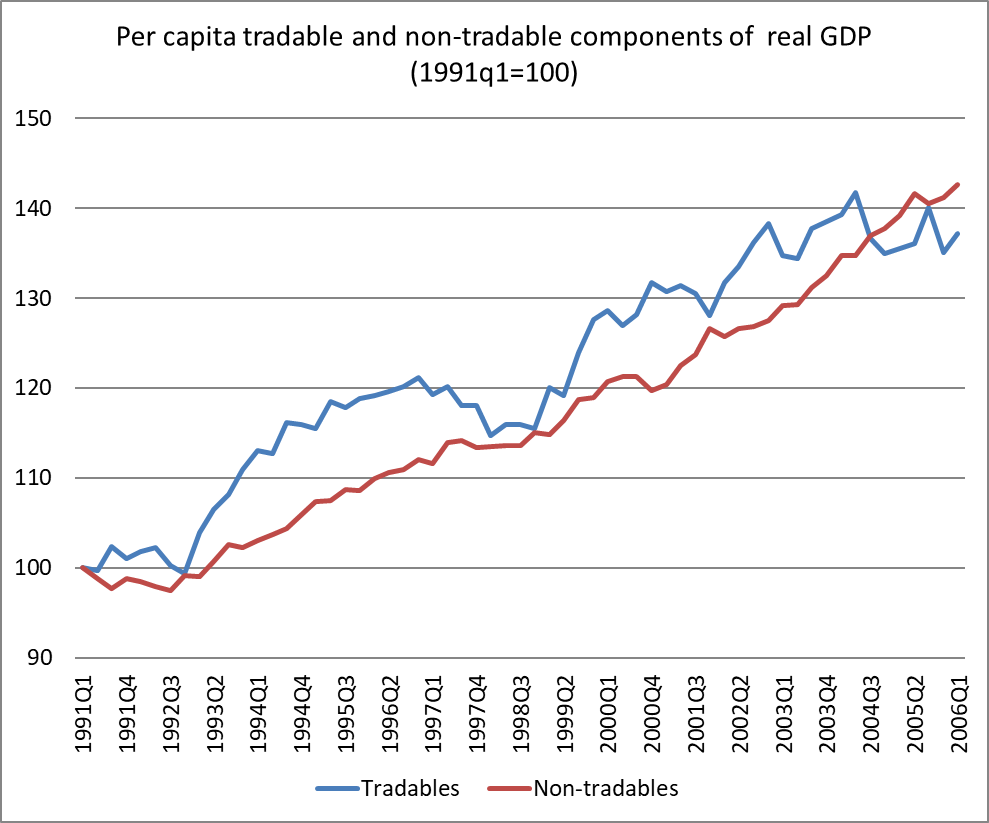

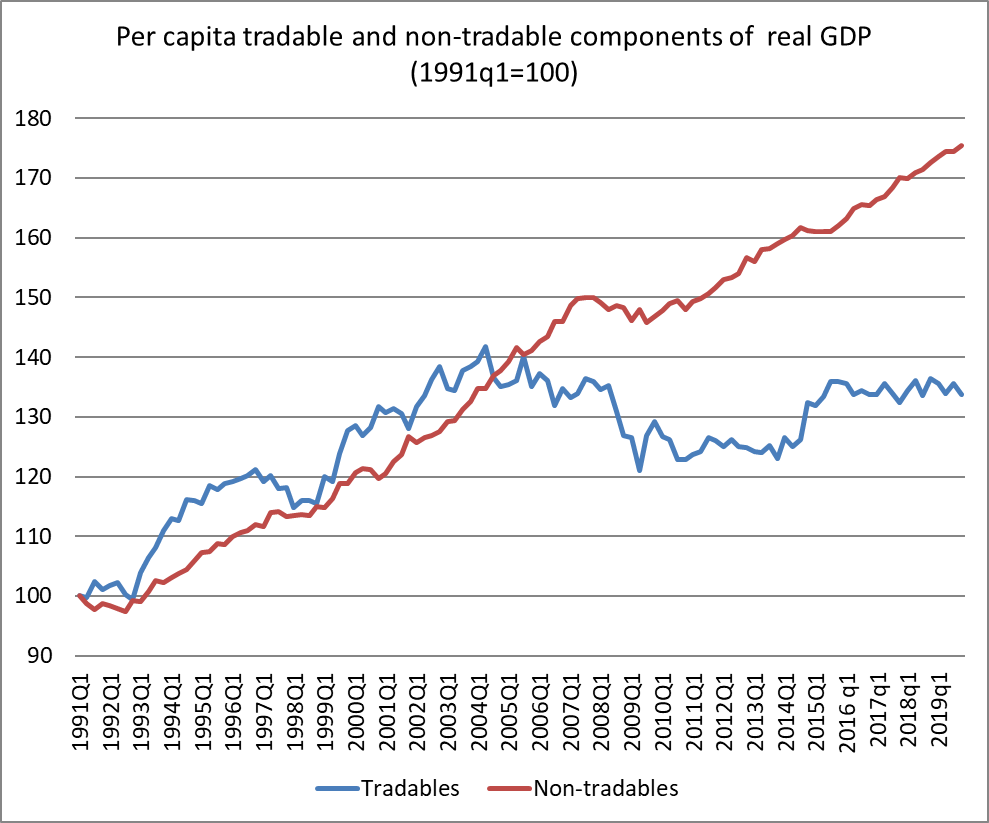

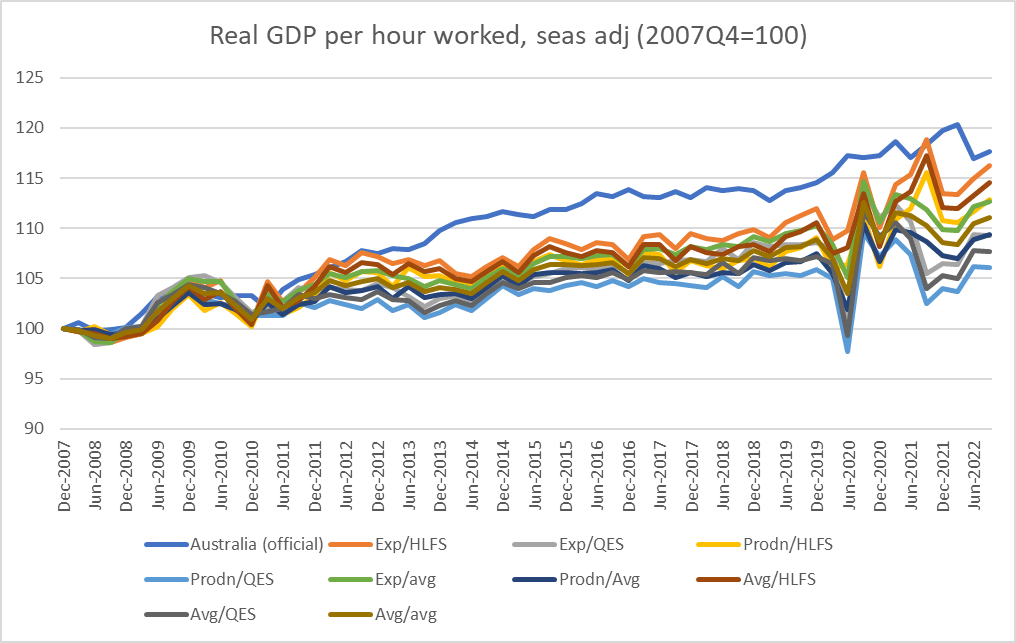

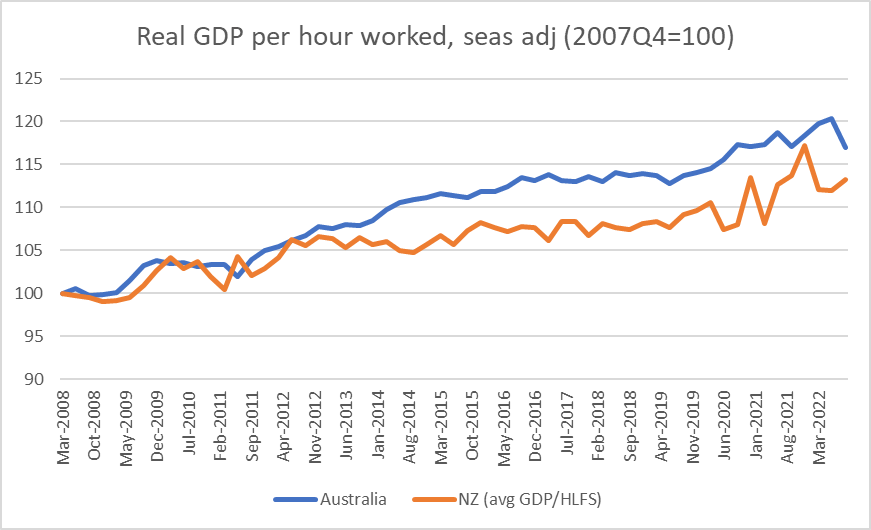

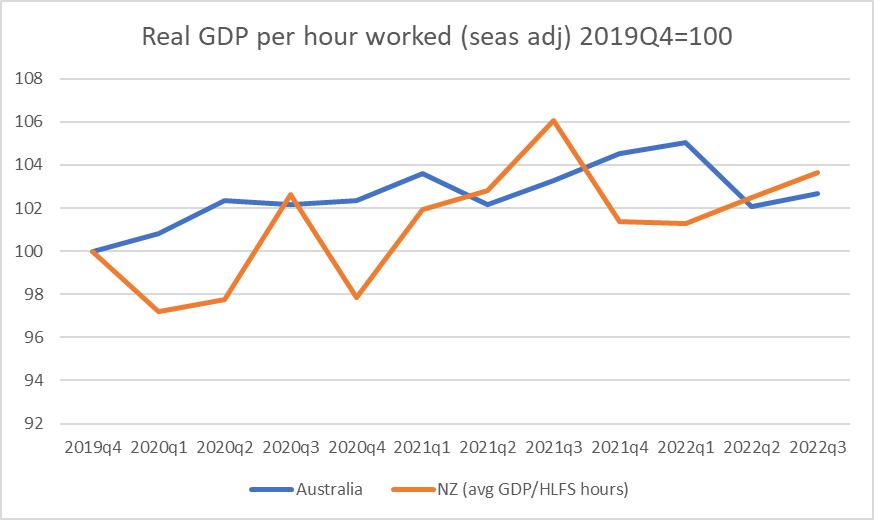

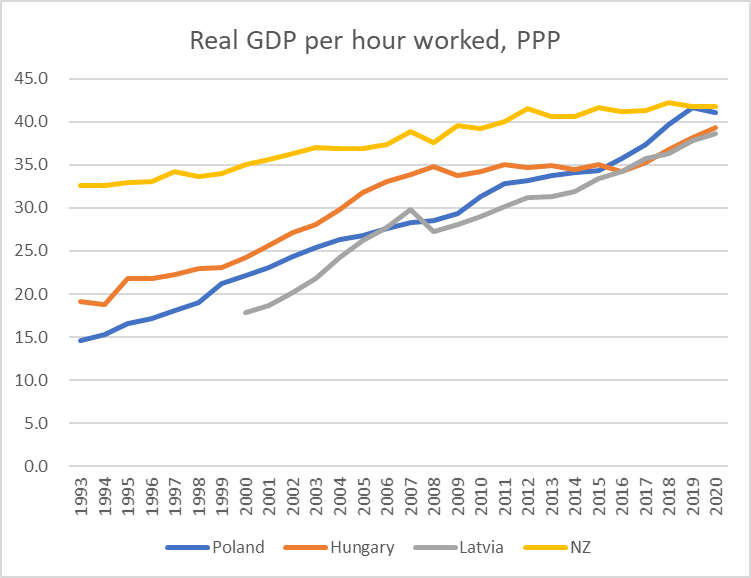

And then there is myth 2. Bryce and I have debated this point on many occasions over the years, and I’ve written about it here before. I can’t prove that he, or Roger Kerr, have not been surprised at how poorly the New Zealand economy has performed over the last 30 years, or by the failure to even begin to close the gaps with the OECD leaders, or by the widening productivity gaps to, notably, Australia. But I’m pretty sure most people who supported the reforms don’t think outcomes have lived up to their expectations and hopes. I recall the very first time I ever appeared before a select committee it was with the Bank’s then chief economist to tell MPs our story about how as we emerged from the reforms we would expect multiple years of above-average growth, consistent with closing the gaps to the rest of the world.

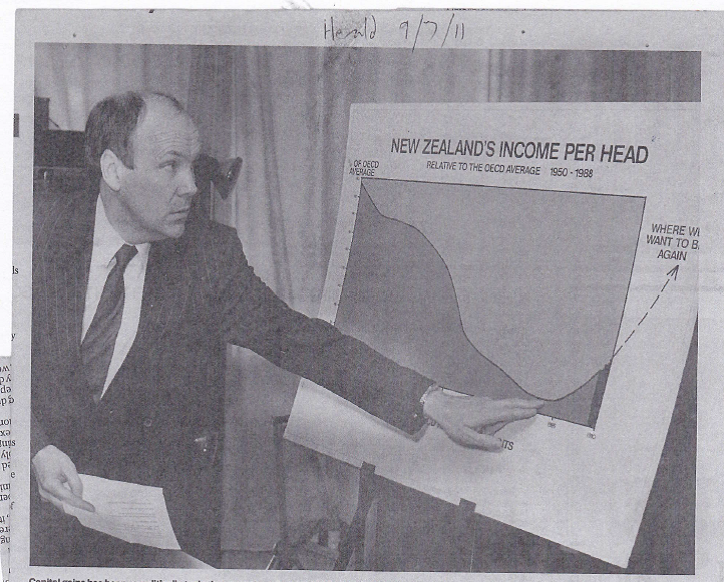

But to me the single best illustration of the point was this photo, from 1989 but rerun in the Herald a decade ago

For the younger among you, that is David Caygill, then Minister of Finance and one of the foremost reformers. It is pretty clear he expected the reform programme – which was extended after his time – to pay off in closed productivity/GDP gaps. It is also clear that it didn’t.

Bryce Wilkinson thinks more should have been done, and could have been done. He was a member of the 2025 Taskforce a decade ago on closing the gaps to Australia. But even if he is right on that – and on some specifics I agree with him – I’m not sure what is gained by continuing to run the line that the economic outcomes really weren’t disappointing or unexpected at all.

To close, the New Zealand Initiative’s report ends up being a funny beast. For better or worse, most people probably won’t care about the pre-84 history, and it isn’t clear how much relevance the specifics have to today anyway. And if there is a lot wrong with this government’s economic policy (and there is) this report is too once-over-lightly (and a little florid in places, given our relative macro stability) to add much value or get much traction. Perhaps there is still a place for debates about the 1984-93 period – in fact there definitely is, even granting that to many younger people it is (my daughter’s phrase) “ancient history” – but to do so usefully probably needs more space, more nuance, and more data than is in the relevant section of this report.