I’ve been intrigued for some time by the way in which some Australian business and media leaders seem to think that New Zealand – perhaps especially under the stewardship of the current government – is a model of governance and economic management to be emulated. Indeed, when it suits, this idea even reaches all the way up to some politicians. On the day of his successful party-room coup to topple Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull declared

“John Key has been able to achieve very significant economic reforms in New Zealand by doing just that, by taking on and explaining complex issues and then making the case for them. And I, that is certainly something that I believe we should do and Julie [Bishop] and I are very keen to do that again.”

As I noted in a post at the time, the list of “very significant economic reforms” was so short I couldn’t think of any.

What puzzles me more is when senior New Zealand commentators buy into the same story. Fran O’Sullivan’s column in the Herald yesterday, “Oz needs the English influence” seemed to do exactly that. It is interesting to know how some influential Australians see the New Zealand story, but O’Sullivan seems to share the belief, noting that our economic performance is “something to skite about when it comes to transtasman rivalry”.

Of course, everyone knows Australia has its problems. They still have a federal government budget deficit, and we don’t. The Prime Minister has changed so often in the last decade, it must almost look familiar to Italians. And in Wayne Swan and Joe Hockey, they’ve had a couple of Treasurers who didn’t command much respect. And Australia is coming off the back of a massive mining investment boom – in many respects a nice problem to have, and in contrast to the lack of much of market-led export-oriented business investment boom in New Zealand any time in recent decades.

And, of course, if the National-led governments of the last eight years have all been minority governments, John Key and Bill English mostly seem to have managed the politics quite adeptly: they are still in office, and look to have a reasonable chance of winning again next year. And English is a thoughtful Minister of Finance, even if not one with much of an economic plan.

But one can always find thoughtful individual ministers – I recall reading speeches by Craig Emerson, a minister in the Rudd/Gillard governments and a former senior public servant, and wishing we had ministers who could give such thoughtful and rigorous speeches.

And Federal systems, and bicameral Parliaments, are just harder to manage – but not necessarily worse for it – than the New Zealand system.

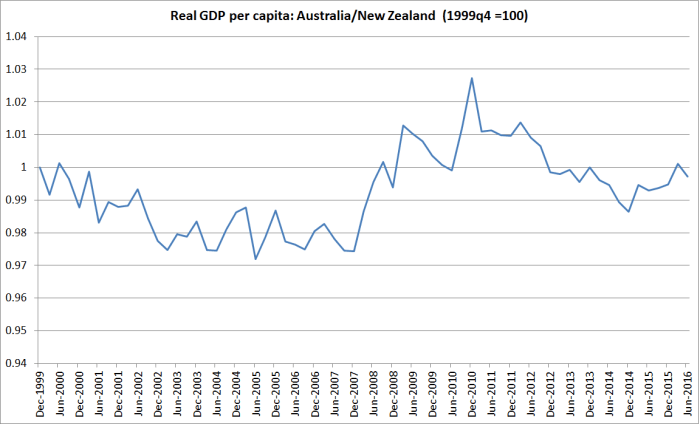

My benchmark remains the numbers. It is no secret that GDP per capita (and all variants on it) is much higher in Australia than in New Zealand. That has been so for at least 40 years. It is the reason why lots of New Zealanders move to Australia, and only a small number of Australians come to New Zealand.

But I guess that in thinking about the Australian Key-English admiration the focus should really be on how the data have changed in the last few years. Has the vaunted Key-English style and substance succeeded in changing direction, closing the gaps between New Zealand and Australia? After all, John Key was once quite explicit that his goal was to close the income gap between New Zealand and Australia by 2025.

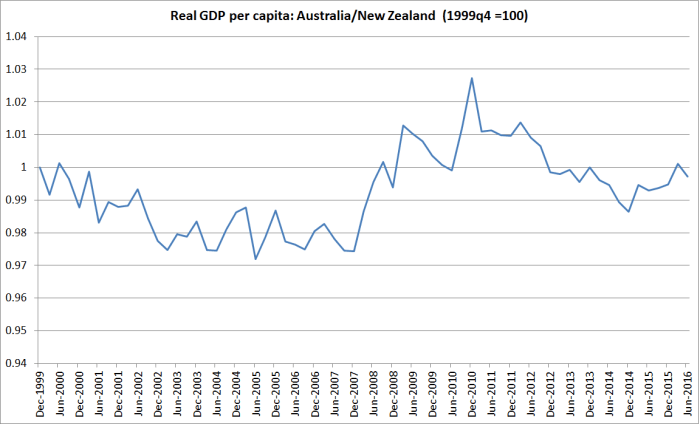

Here is the headline comparison, looking at real GDP per capita

On this measure, Australia was doing slightly less well than us during the previous boom. They did much better than we did through the recession and the peak of the terms of trade boom. And over the last few years, things have settled back again. For the whole period – this century to date – New Zealand and Australian per capita GDP have grown at much the same rate.

New Zealand and Australian governments have almost no control over the respective terms of trade for their countries, and those series are quite volatile. But if you dig into real per capita income measures (which take account of terms of trade fluctuations), New Zealand has done slightly better than Australia over the century to date.

But that seems to me to be about the absolute limit to the favourable story.

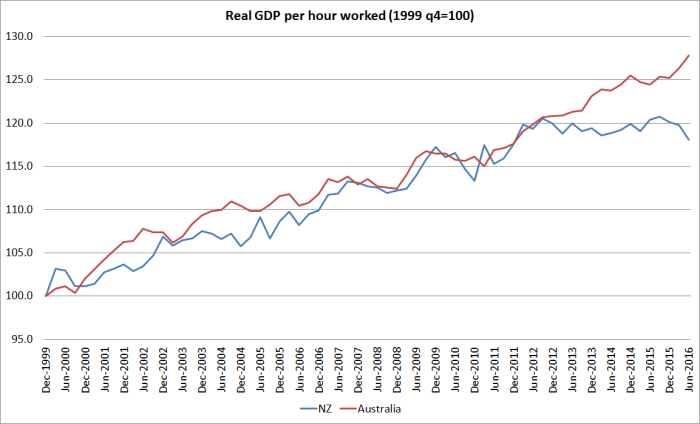

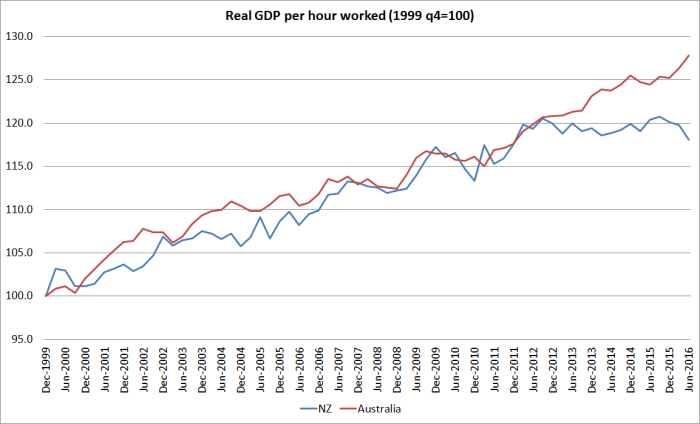

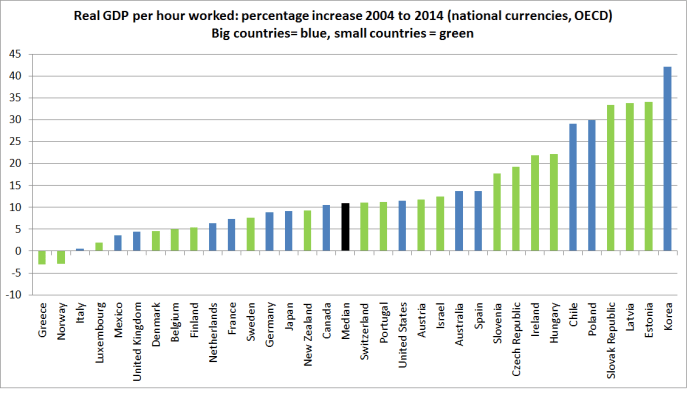

What about productivity growth, the foundation for sustained long-term prosperity? Here is labour productivity

You can discount the very last New Zealand observation (on account of a break in the hours worked series, when SNZ updated the HLFS methodology). But it isn’t exactly a picture which reflects well on New Zealand over the last few years (and especially the years when both countries have had centre-right governments). In fact, the New Zealand numbers are so bad one half suspects SNZ might eventually revise some of the weakness away. But in the meantime, no obvious advantage to New Zealand.

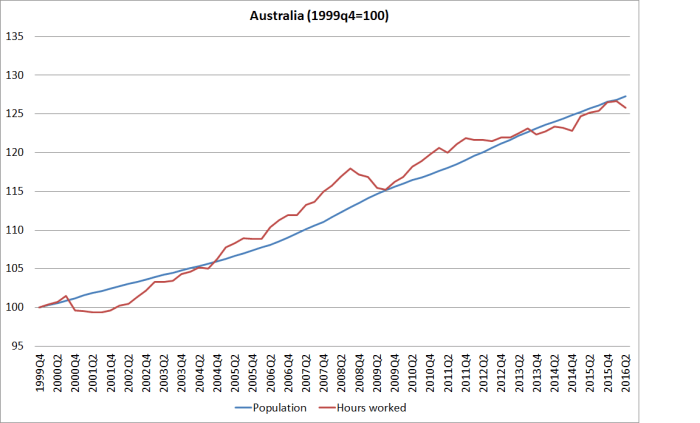

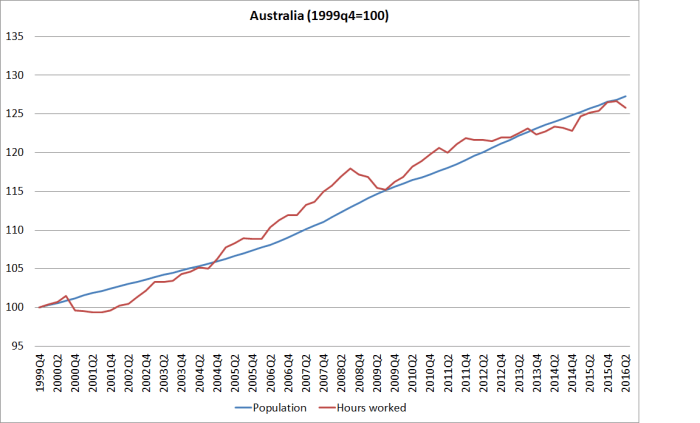

We’ve managed not to lose any more ground relative to Australia on GDP per capita. but only by working even more hours. Here are Australia’s hours worked and population data

And here is New Zealand, on exactly the same scale (and again, discount the very last hours observation).

Of course, there is nothing wrong with working longer hours if that is what individuals choose, but for whole economies it isn’t usually a sustainable path to greater prosperity. And while productivity gains are pure benefit, longer working hours – especially with little or no productivity growth – is mostly just a cost.

In some areas, New Zealand does typically do better than New Zealand. Our labour market is less heavily regulated than Australia’s – and much less subject to union corruption – and, as a result, our unemployment rate is typically a bit lower than Australia’s. Here are the two unemployment rates over the last few decades.

Right now, the gap between the two unemployment rates – 0.6 percentage points – looks about normal. But for much of the current government’s term what was striking was how high our unemployment rate lingered (and above Australia’s for several years). It isn’t obvious that any special credit is due to the current New Zealand government.

But what about government finances?

It is certainly true that our central government has a modest surplus, while the Australian federal government is still in deficit. But recall that Australia has a federal system, and the state budgets make up quite a large proportion of overall government spending and revenue. International agencies tend to focus on “general government” data – central, state (where relevant) and local government. Cyclical adjustment also matters.

Here is OECD’s latest estimates of the cyclically-adjusted general government estimates for the two countries.

Almost indistinguishable not just now, but over most of the last 20 years. I’m not sure I’m totally convinced, but that is the OECD’s read. Again, nothing that particularly stands out to the credit of English/Key relative to Australia.

Almost indistinguishable not just now, but over most of the last 20 years. I’m not sure I’m totally convinced, but that is the OECD’s read. Again, nothing that particularly stands out to the credit of English/Key relative to Australia.

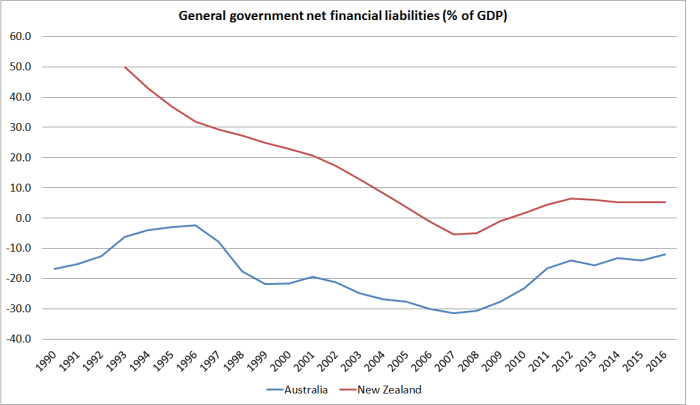

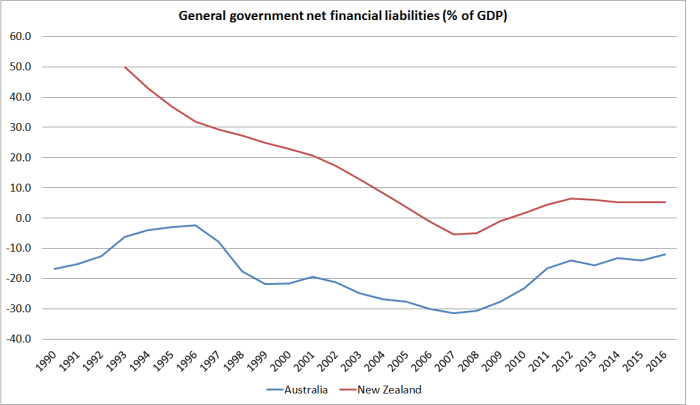

And here is the OECD data on government debt (net liabilities, across all three tiers of government) as a share of GDP.

New Zealand governments did a great job getting net debt down in the 90s and 00s, but New Zealand’s net debt is still higher than Australia’s. Since the last pre-recession year, 2007, Australia’s debt has increased more than New Zealand’s (share of GDP). That probably is to the credit of Key/English, especially given some of the earthquake fiscal pressures, but on this measure, Australian governments’ net debt is still a bit less than ours was in 2007.

Business leaders also tend to believe – as I do – that, within limits, smaller government and lower taxes are conducive to better long-run productivity growth. Stability in the share of GDP spent by government is also generally thought to matter (reducing uncertainty about future tax rates).

Here is general government spending as a share of GDP.

Not only is Australian government expenditure lower as a share of GDP, but it is more stable. And the gap between those two lines has not narrowed over the Key/English years; if anything it has widened.

And here is the picture of revenue

There isn’t much of a story about variability – really big terms of trade fluctuations generate a lot of revenue volatility – but again Australian government revenue (mostly taxes) is consistently materially lower than that in New Zealand.

So I’m still a bit puzzled why the Australian business people and commentators seem so taken with the New Zealand story. There is (almost) nothing there. No serious reforms and (to the extent any disagrees with that assessment) no significant productivity growth. No sign of the gaps closing. The size of government is bigger here, but then it has been for a long time. And, more positively, the unemployment is a lot lower here, but again current numbers aren’t out of line with past patterns.

I presume much of it just comes down to two things:

- whenever elites in any country are discontented with their own governments, it is easy to contrast them with some other group of politicians (whose own record is rarely examined closely) over the water,

- the National-led government has been able to count (law changes it proposes mostly happen, and the details of the languishing RMA reforms are no doubt lost on opinion formers in Australia). But then it is great deal easier to “count” here, where typically National needs one or two votes from parties it has longstanding confidence and supply agreements with. It is just harder in Australia, between the role of the states, a governing bloc that is itself a coalition of the Liberal and National parties (National MPs having no say in who is Liberal leader and PM), and the Senate where it is rare for any party to be able to command a stable majority.

John Key and Bill English might be more successful politicians than Rudd, Gillard, Abbott, and Turnbull: the New Zealanders have won three elections, and the Australians have won only one each, and the first three have then been ousted by their own parties.

Perhaps that sort of political stability/political success has its own appeal in certain circles, but if we are judging political leaders by their fruit, there is still nothing much about the New Zealand economic story that should prompt any envy in the eyes of our trans-Tasman neighbours. Sadly……still……after decades and decades.

Rugby might be another matter, but then I’m a cricket fan.

Almost indistinguishable not just now, but over most of the last 20 years. I’m not sure I’m totally convinced, but that is the OECD’s read. Again, nothing that particularly stands out to the credit of English/Key relative to Australia.

Almost indistinguishable not just now, but over most of the last 20 years. I’m not sure I’m totally convinced, but that is the OECD’s read. Again, nothing that particularly stands out to the credit of English/Key relative to Australia.

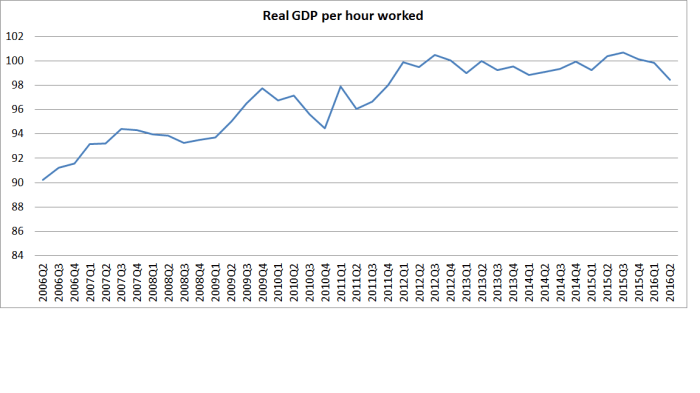

No productivity growth at all in the last four years or so (even ignoring the last observation, where there is an unfortunate discontinuity in the HLFS hours worked series).

No productivity growth at all in the last four years or so (even ignoring the last observation, where there is an unfortunate discontinuity in the HLFS hours worked series).