A speech appeared on The Treasury’s website the other day. It was, we were told, by Gabs Makhlouf, Secretary to the Treasury, and given as the closing address at a Productivity Hub Workshop last Friday. The Productivity Hub is a grouping of government agencies, hosted at the Productivity Commission

which aims to improve how policy can contribute to the productivity performance of the New Zealand economy and the wellbeing of New Zealanders

It is a laudable aim. I’ve been to a few of their events, and at times they’ve had some interesting and stimulating speakers. Whatever the event was that Makhlouf was speaking at, it has a very low profile – there is nothing about it on the Hub’s homepage, or anywhere else I can see. I’ve lodged a request for the papers and presentations.

I’m all in favour of pro-active release of material by government agencies, but I was a little curious why The Treasury chose to make this speech something on-the-record. Closing addresses usually seek to summarise and draw lessons from what has been heard at the conference/workshop. But in Makhlouf’s speech there is no reference to any of the papers that had been presented, or any of the material discussed at the workshop. Perhaps he just wanted to signal that he, Secretary to the Treasury, treats productivity as something important (on checking, I found that Treasury had also published his brief remarks to a couple of previous Productivity Hub events)?

Whatever the reason, when the Secretary to the Treasury – head of the government’s main economic advisory agency – talks about productivity, it should be worth taking note of. After all, presumably even now Treasury is in the process of pulling together the analysis and advice that will form the basis for their Briefing to the Incoming Minister (BIM) after the election. We might hope they will be (a) pointing out to the Minister of Finance that New Zealand’s productivity performance is woeful, and (b) offering a compelling narrative and set of recommendations for what might reverse that performance and enable New Zealand to deliver for its citizens the sort of standard of living they should reasonably expect. But on the basis of the Secretary’s latest speech, I wouldn’t be holding your breath.

Of course, one can’t expect any sort of fully-developed story in a few pages closing a workshop. But if there is (a) a sense of urgency, and (b) a well-developed set of policy proposals being worked-up, that should be clear in a speech of this sort. Neither is there.

Makhouf recognises that our productivity performance leaves something to be desired, but how is this for minimising the issue?

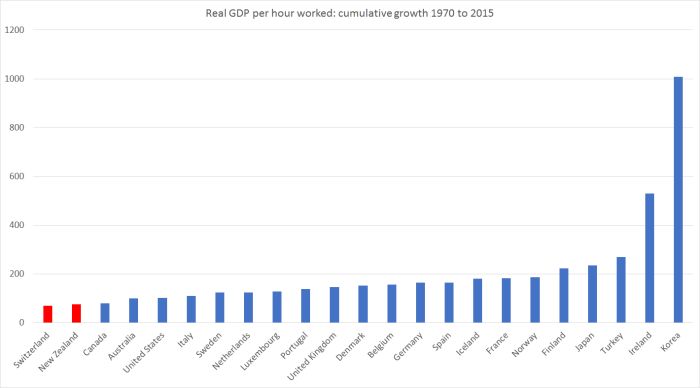

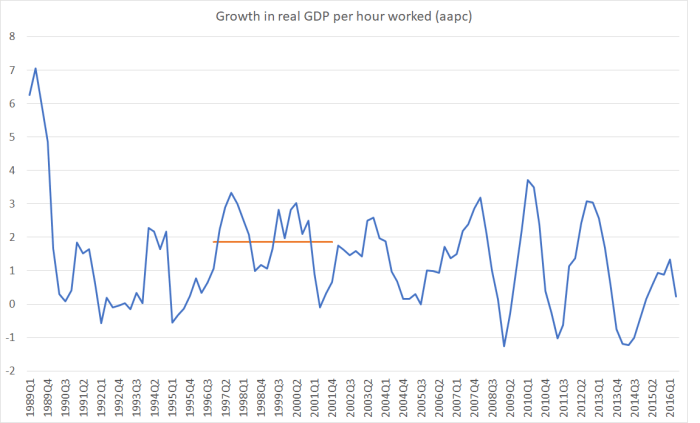

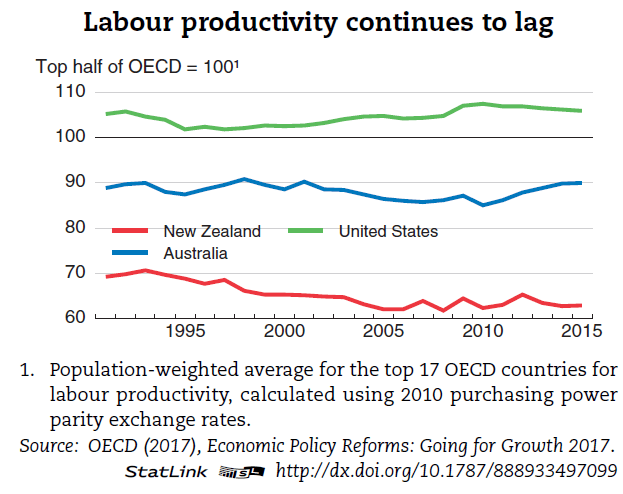

We are middle of the OECD pack at best in the amount of income we derive per hour worked, and we have made little or no headway on lifting our productivity performance rankings over the past 15 years.

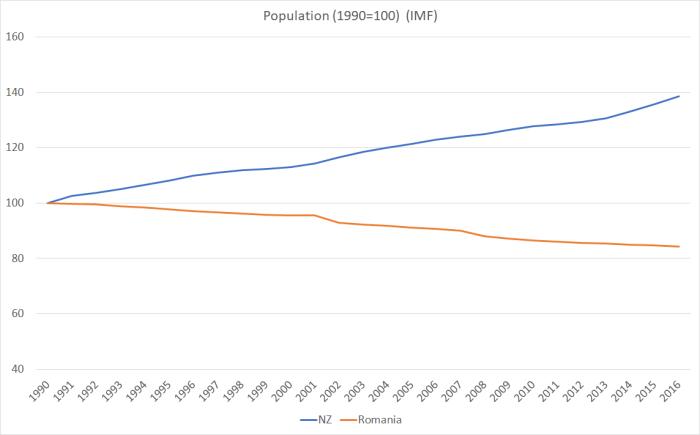

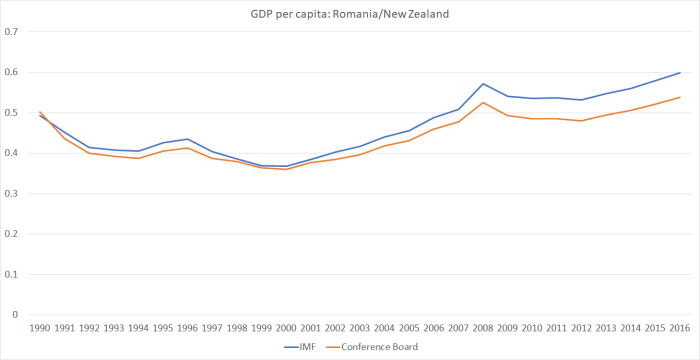

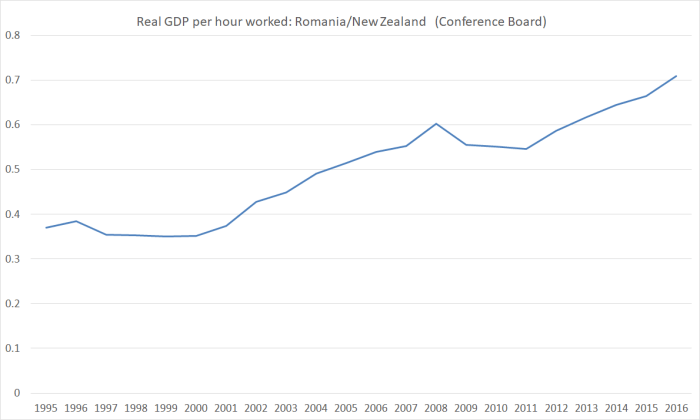

There are 35 OECD countries now, and only 13 had real GDP per hour worked less than New Zealand’s in 2015 (most recent comprehensive data). And the only reason we are even near the middle of the OECD pack is because so many poorer countries have been allowed into the OECD. Every single one of the 11 new members in recent decades was poorer, and less productive than us, when they joined.

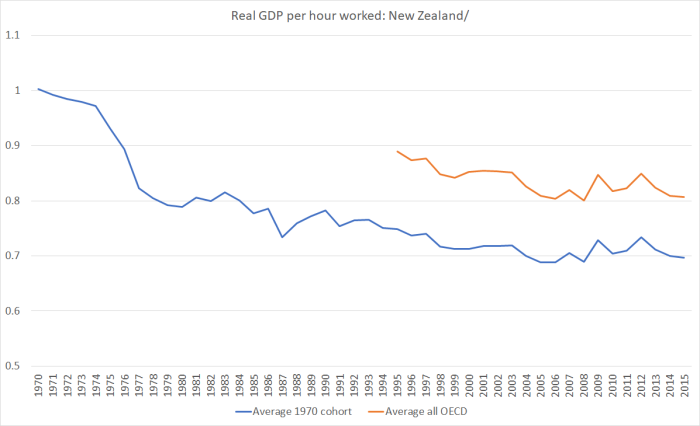

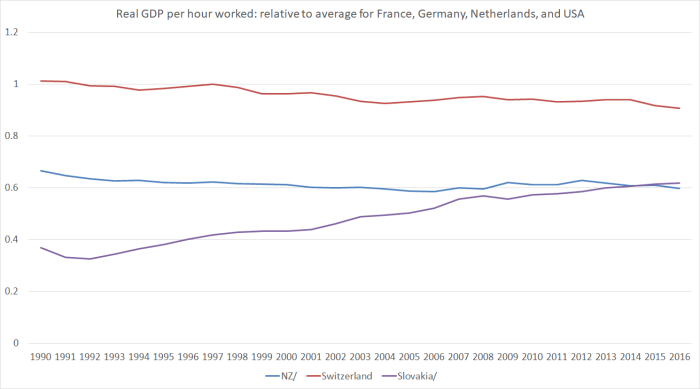

When we joined the OECD in 1973, it was a club of 24 countries. OECD data go back to 1970. And in 1970, our real GDP per hour worked was similar to that in France and Germany. These days, they have productivity 60 per cent higher than ours, and of those 24 countries only Portugal, Turkey, and Greece now have lower real GDP per hour worked than we do. In 1970, Turkey had GDP per hour worked less than half ours, while on the latest estimates it is now almost equal to us.

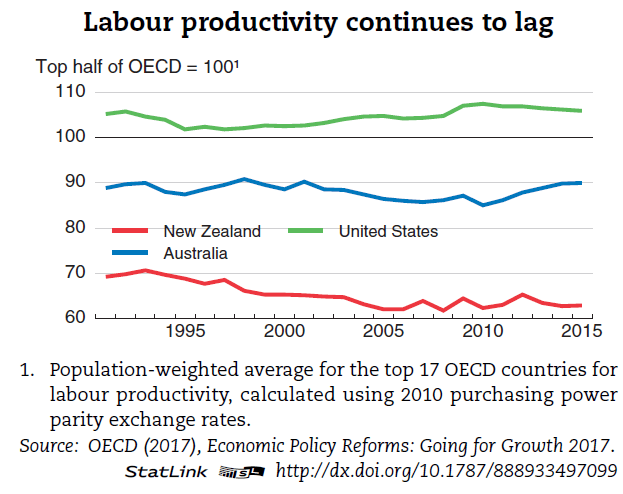

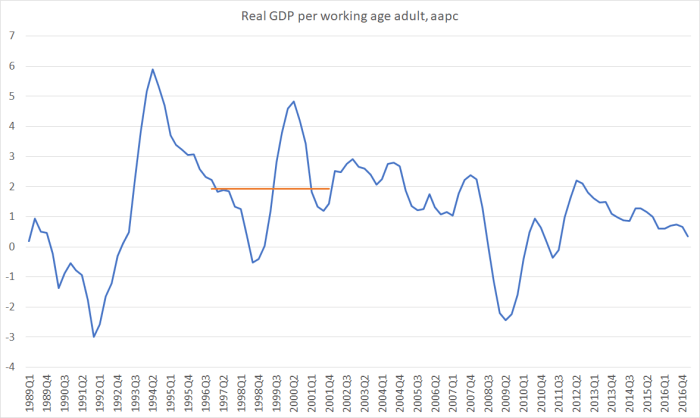

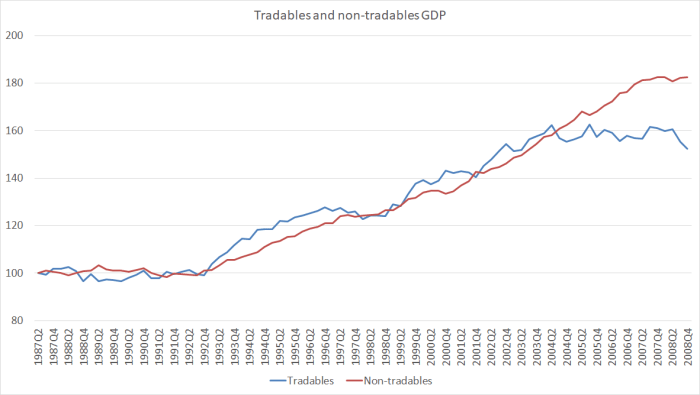

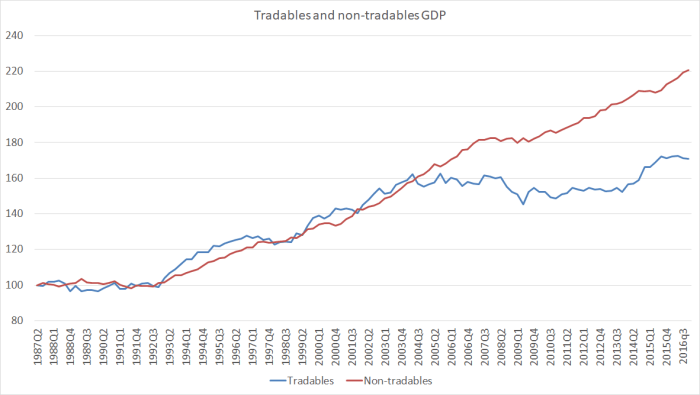

And while it is certainly true that “we have made little or no headway on lifting our productivity performance rankings over the past 15 years”, the story is much worse than that, as even the OECD highlighted last week. Here is their chart

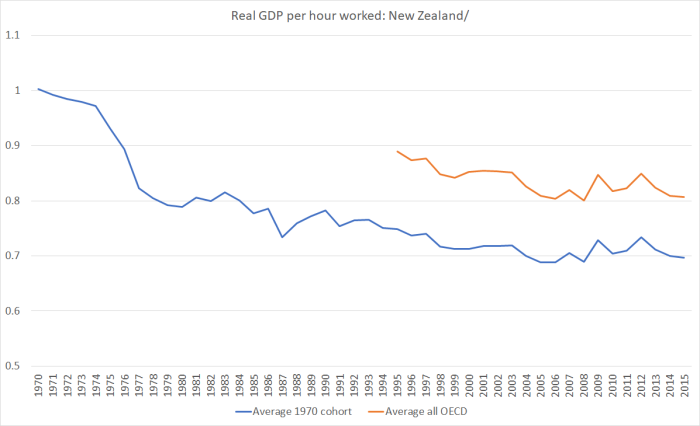

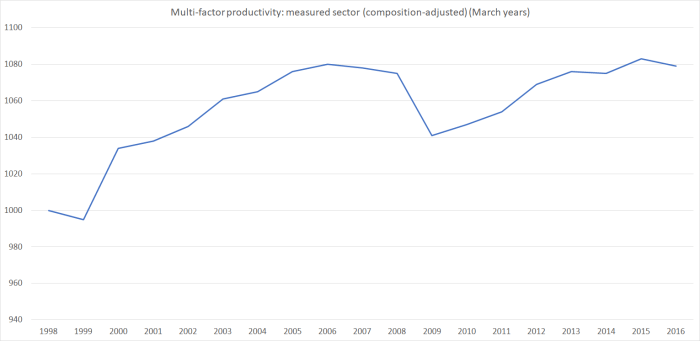

And this is mine, from a post a couple of weeks ago

In 47 years now there has never been a time when New Zealand has succeeded in narrowing the productivity gaps that have opened up between us and other advanced countries. At best, we’ve gone sideways in some periods.

And if Makhouf understates the severity of the problem, he overstates any signs of progress

Our understanding of New Zealand’s productivity performance is improving, thanks to a wealth of information that has recently been released including as a result of the Productivity Commission’s report Achieving New Zealand’s Productivity Potential, the OECD’s New Zealand Country Study and Going for Growth, and the Treasury’s He Tirohanga Mokopuna. (That last one is a cracking read, by the way.)

Really? The Treasury report he refers to was their long-term fiscal report, and I’m genuinely puzzled as to how he thinks that (useful) report advances our understanding of the productivity underperformance. The Productivity Commission piece, which I wrote about here, was an interesting effort, and did represent a step forward in some areas (including the treatment of immigration policy) but it has hardly galvanised the nation – or even, as far as I can tell, official Wellington. As for the OECD’s report, surely Makhlouf was just being diplomatic – the OECD chief economist was at the workshop – rather than seriously suggesting that they have a compelling narrative to explain New Zealand’s underperformance and, thus, a solid model to use in proposing remedies?

Makhlouf goes on

Our challenge now is to keep building the momentum of progress and turning our growing understanding into action that lifts our productivity performance.

But where is the progress at all? Where, specifically, is the evidence that Treasury – or other government agencies – are any closer to credible answers?

Makhlouf set out what might have been an interesting marker

As I mentioned, we have seen little improvement on where we rank among OECD countries for productivity, yet we have been told that we have world-leading settings.

This raises a few questions for me. ….. Or could it in fact be that New Zealand’s world leading economic and policy settings aren’t so world-leading anymore?

I’m not sure who really thinks of New Zealand policies are being “world-leading” these days. In some areas, perhaps they are. In other areas, we score quite badly. But I’d have thought a fair overall description would probably be ‘no worse than the typical OECD country’.

Sadly, Makhouf doesn’t really do much to develop his tantalising question.

‘World-leading’ is always evolving. Looking back through history, Rome, China, India and the United Kingdom have all at times been world leading economies, just as the United States is today. So while some things will continue to hold for productivity and incomes, we need to make sure we are not working towards something that used to be world-leading, but is no longer so. It’s also likely that what’s world-leading will vary by country so it’s not a recipe that we can simply copy.

Surely all this confuses great power status – not unrelated to economic strength typically – with world-leading (economic) policy settings? After all, he could have noted that 100 years ago, New Zealand looked pretty world-leading – not as a “great power” but as one of the very richest and most productive nations on earth. Nor am I really quite sure how “what’s world-leading will vary by country” makes much sense, unless he is saying – in which case I agree – that in thinking about diagnosing New Zealand’s problems and offering remedies to policymakers we need to think hard about the specifics of New Zealand’s situation. It isn’t clear that the OECD (at least) has really done that.

But it isn’t clear that Treasury is really doing so either. Because Makhlouf devotes the rest of his remarks to

five factors that the Treasury believes always matter: skills, connections, markets, resources and rules.

Any micro-focused policy agency almost anywhere in world could trot out that list

Of skills

The Treasury believes that opportunities remain to lift skills and resilience in the workforce, and it’s important that those opportunities are pursued.

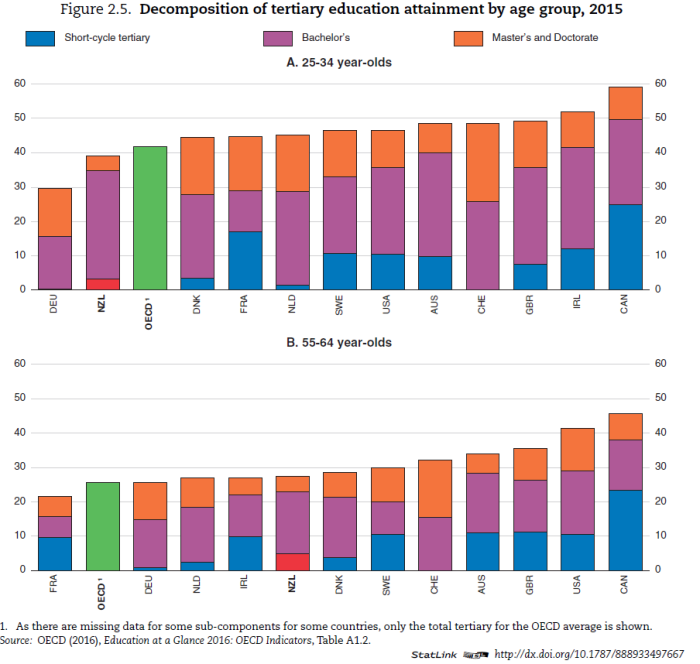

No doubt, but it doesn’t seem particularly persuasive that gaps here are big part of the 45 year story of underperformance, when the OECD adult skills data suggests New Zealand workers already have among the highest skills of any in the OECD.

Of connections

Connections matter, in particular people-to-people connections. And as Asia continues to dominate economic activity, perhaps those types of connections – ie, relationships – matter more than ever. Improving connections can help to improve the flow of people, capital, trade and ideas that contribute to productivity. Strong people-to-people relationships build confidence and understanding and promote learning. They help our businesses to identify capabilities that will help them improve their productivity and ultimately compete and succeed in both domestic and global markets.

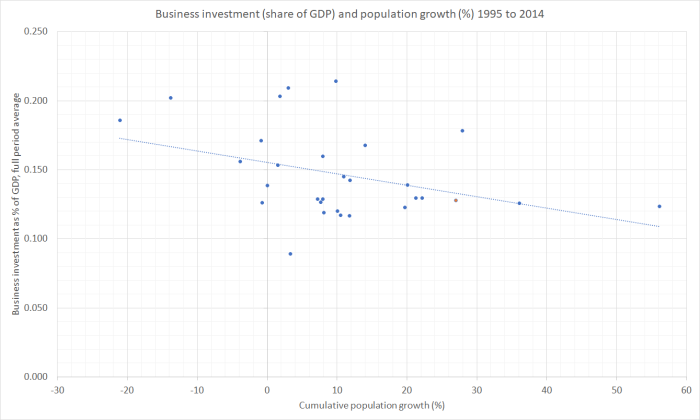

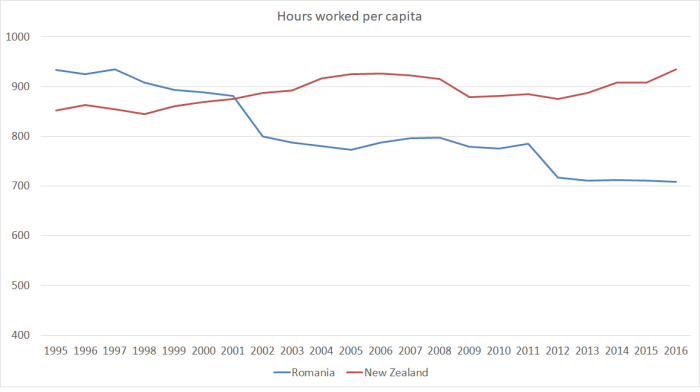

I suspect this is some sort of code for “keep on having lots of immigration”, but it isn’t terribly specific. And as a reminder, with rare exceptions, Asia isn’t the home to the richest or most productive economies. But again, with hugely high (by international standards) rates of non-citizen immigration, did Makhlouf and Treasury have anything remotely specific in mind?

He gets a little more specific on “markets”

In the Treasury’s view we need to continue to lift the competitive intensity of the New Zealand economy. The pressure of competition pushes firms to be more productive, for example by innovation to improve quality or cut costs. We need to ensure our markets are as competitive as possible by reducing the barriers to entry, including for imports (whether in goods or services), or by regulating the price and quality of goods and services in markets where there is little or no competition, such as in our telecommunications and electricity markets. And we need to maintain the effectiveness of competition laws and institutions. If we want competitive markets and the productivity gains they bring, we have to ask ourselves: what are the regulatory barriers preventing competition and what can we do about them? How bold do we want to be to invite competition?

It isn’t really my area, but if there is useful stuff to be done in this area how plausible is it that it can materially explain 45 years of relative economic decline? Say what you like about competition in New Zealand now, but in almost all areas there is a great deal more than there used to be.

Then he moves onto natural and physical resources. Here he includes housing.

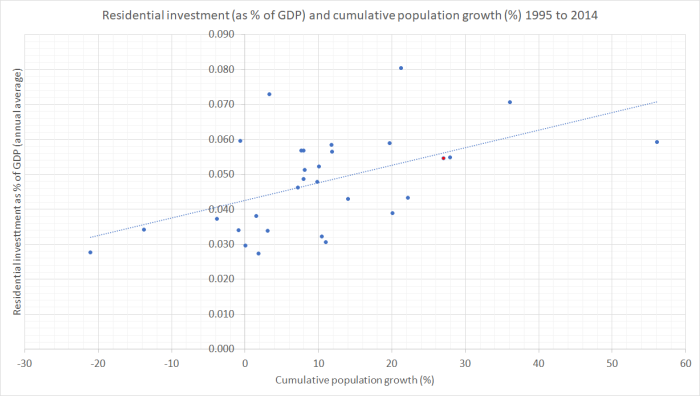

Our natural and physical resources are next. One of the most high profile issues we’re examining in New Zealand – housing – illustrates how these resources are a significant factor in productivity. We are all aware of issues in house price growth in Auckland and the inefficiencies in our use of land which are proving to be a bottleneck in New Zealand’s growth and productivity.

I’m not sure there is really any evidence for this proposition. If there is, in a New Zealand context, perhaps The Treasury could publish it. Dreadful as our housing policies are, when the city that is worst affected by them has (a) had very rapid population growth, and (b) has a very small margin by which productivity exceeds that in the rest of country, it suggests that overseas studies – on places like San Francisco and New York (which have had little population growth, and very high productivity margins) – may not be of much direct relevance here.

Still on housing

the degree of its affordability or unaffordability is a product of our entire urban development chain and of multiple interacting areas of policy. We’re considering these issues holistically, as well as particularly how land owners capture the economic rents and potentially magnify the problems. We see the concept of competitive land markets as an important part of the way forward.

Surely if there is something there, it could have been written a great deal more simply? And portentous words about “the concept of competitive land markets as an important part of the way forward” almost make a mockery of people priced out of home ownership right now.

In some areas, I’m not sure Makhlouf really knows what he is saying

At the moment, it can be argued that too much of our natural resource use is determined by incumbency rather than most efficient use.

Does inumbency here mean “the person who owns it”? But, surely, land is our greatest natural resource. Mostly, it is pretty freely tradable. Anyone with a better, more profitable use, in mind can surely make an offer? Or (but surely not) is the Secretary perhaps a bit worried about private land ownership?

Actually, despite what he said, he seemed to be mostly talking about water rights and pollution. What he says on water sounds sensible

To use water as an example, the ‘first-in first-served’ approach to water allocation means it may not always be allocated to the highest value use, and the current system lacks sufficient incentives for use to move to a higher value one. The Freshwater Allocation Work Programme is considering options that could be more appropriate to ensure that we are getting the best use of our water resources.

And I’m sure there are some real issues around pollution too. But when he says

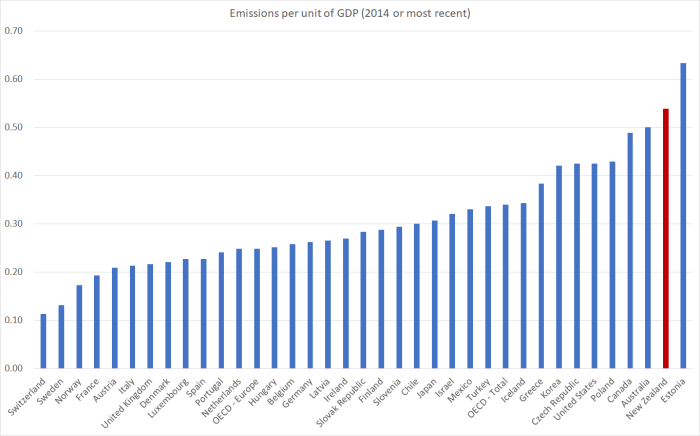

Better rules around use and around pricing externalities such as pollution are critical to making best use of resources and are likely to be key to promoting significant diversification of the economy and contributing to an improvement in productivity.

I think he makes it sound all too easy. For example, it is all very well to talk of water pollution arising from more intensive dairying, or indeed of the implications for carbon emissions, but without a great supporting analysis it sounds a lot like feel-good rhetoric to suggest that restricting such industries is likely to be significant in lifting overall productivity in the economy. What channels, one wonders, does the Secretary have in mind?

His final category was rules

The making of rules and regulations – whether by central or local government or even by self-regulated occupational groups – has an impact on productivity. All rule-makers help shape the environment in which investment, enterprise, and job creation is either promoted or limited. Rule-makers in the public sphere have a double responsibility: to ensure effectiveness in public spending and decision-making, and to provide the best possible regulatory and policy settings.

Hard to disagree really. But is this really the best the Secretary to the Treasury – an agency with key responsibility for regulatory review policy – can do on the contribution of New Zealand regulation to productivity? There isn’t even an attempt to draw some of his points together, and note that (for example) well-intentioned but flawed rules help explain the absence of a well-functioning market in urban and peripheral land.

Overall, there is no sense of urgency, and no hint of any fresh insights either.

Makhlouf ended his speech this way

We need to continue to test our assumptions about what does and doesn’t work, and to apply new things where they make sense. I know there’s a lot of willpower and brain power here to ask questions, find solutions and take actions to raise New Zealand’s productivity.

Of course, it is elected politicians, not officials, who would get to “take actions to raise New Zealand’s productivity”. Sadly, despite the approaching election, there is little sign among any of them – or those competing to take their place – of much will to change, or much interest in attempts at serious answers to decades of decline.

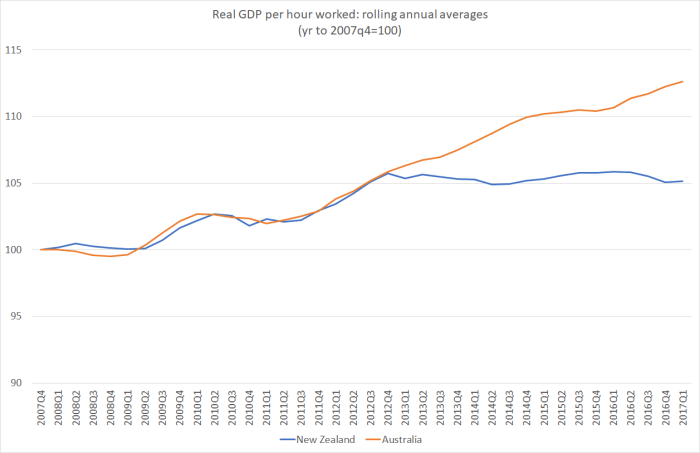

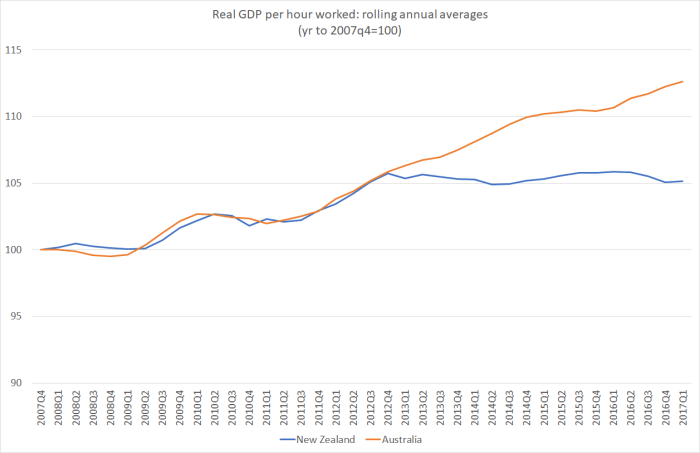

Should there be more urgency? I’d have thought so. There has been plenty of talk in the last few years of New Zealand and Australia relative economic performance. Australia is our biggest trade and investment partner, and of course historically an outlet for New Zealanders pursuing the far higher incomes typically on offer there. It is certainly true that the Australian labour market has been cyclically weak in recent years, even more so than ours. But here is the latest update of labour productivity in the two countries (in NZ, using an average of the two GDP measures, and an adjustment to hours worked for the break in the series last June). The chart is indexed to 2007q4, just prior to the recession, but remember that even then we were well behind Australia (incomes and productivity levels)

As it happens, Makhlouf’s appointment as Secretary to the Treasury was announced on 28 June 2011. We’ve had barely any productivity growth since then (none for the last five years). That, of course, isn’t directly his fault, but one does have to ask whether The Treasury under his stewardship has even once put forward a compelling set of policy proposals to end even this multi-year drought, let alone to reverse the 45 years and more or relative decline. On the basis of this latest speech, we shouldn’t be very hopeful of what they might have to offer a government formed later this year.

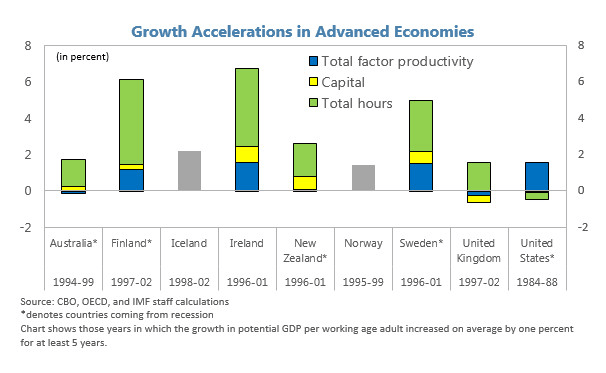

There isn’t anything startling about 1996 itself, but at least on these measures potential output growth in the late 1990s was estimated to have been stronger than before or since.

There isn’t anything startling about 1996 itself, but at least on these measures potential output growth in the late 1990s was estimated to have been stronger than before or since.

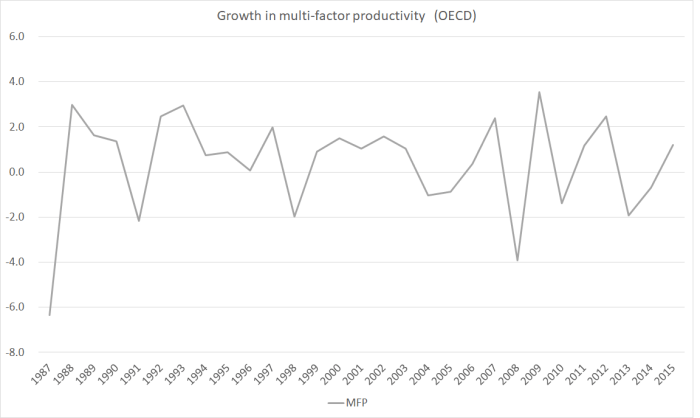

MFP measures are quite cyclical – if plant lies idle in a recession measured MFP will fall – but unfortunately the latest observations are only around the same levels reached a decade ago. There was no MFP growth late in the previous boom. There has been none since.

MFP measures are quite cyclical – if plant lies idle in a recession measured MFP will fall – but unfortunately the latest observations are only around the same levels reached a decade ago. There was no MFP growth late in the previous boom. There has been none since.

(You will recall that New Zealand has been going

(You will recall that New Zealand has been going