A couple of pieces I saw yesterday got me thinking again about New Zealand’s services exports and our economic performance.

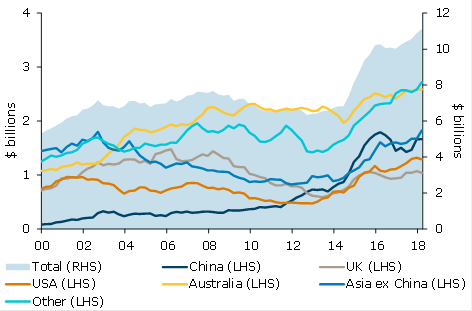

On the one hand, there was an interesting ANZ report on tourism, which included this chart.

Chart of the week

Spending by international visitors has seen impressive growth in recent years.

International visitor spend by country

Source: MBIE

And then there was speech on the MFAT website by Catherine Graham, their Economic Divisional Manager. MFAT doesn’t publish many speeches, so it was interesting to see a bit of an economics angle, even if it was infected with the government of the day’s propaganda. Perhaps that was inevitable to some degree in a speech by a public servant, but gratuitous endorsement of the Provincial Growth Fund didn’t seem strictly required in a speech notionally on “small state diplomacy”.

There was a certain breathlessness to the speech

All countries and regions face technological mega trends that are consequential to businesses and governments and affect decisions. Digitalisation, artificial intelligence and automation will increasingly affect wage and employment levels, in developing as well as developed countries. The key difference from the past is that the change – driven by computing power – will occur at an exponential, rather than linear, rate.

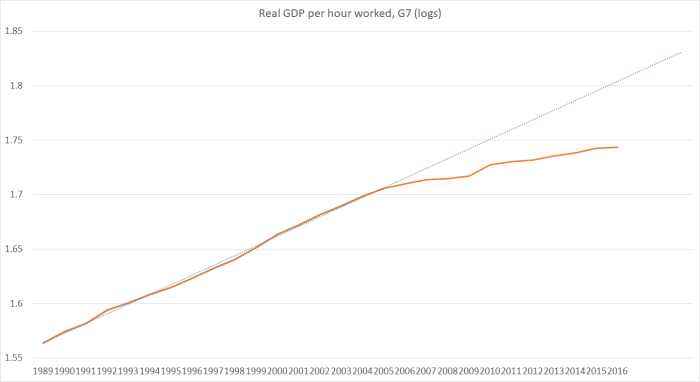

Maybe, although the best guess remains that people who want to work will continue to be able to do so. Markets adjust like that. And global productivity growth shows no sign of such a dramatic transformation (for the better).

Also from the breathless side was this

Non-state actors such as the major e-commerce platforms (think Amazon and Alibaba) and the social media giants (think Facebook, Instagram and Google) are each on their own much bigger economically than New Zealand (and many other countries’ economies). How do we navigate our relationships with them as a nation state?

This seems mostly (a) meaningless or (b) wrong. For example, on checking I learned that the market capitalisation of Facebook was US$390 billion, and its annual revenues were less than US$50 billion. On no meaningful metric is it bigger than New Zealand, but even if it was there is a fundamental difference between a company and a nation state. For better or worse, Facebook could be regulated out of existence almost overnight.

But the line that caught my eye, and prompted this post, was a couple of paragraphs later

Continuing to create and leverage smart ideas will be essential for New Zealand’s agricultural sector to keep delivering value to the economy and address broader societal and environmental challenges. Elsewhere in the economy, New Zealand’s success in weightless exports – such as software development, services embedded and embodied in physical products, and the creative arts – are growing apace. It is likely that this trend will be supported by ongoing technological advances.

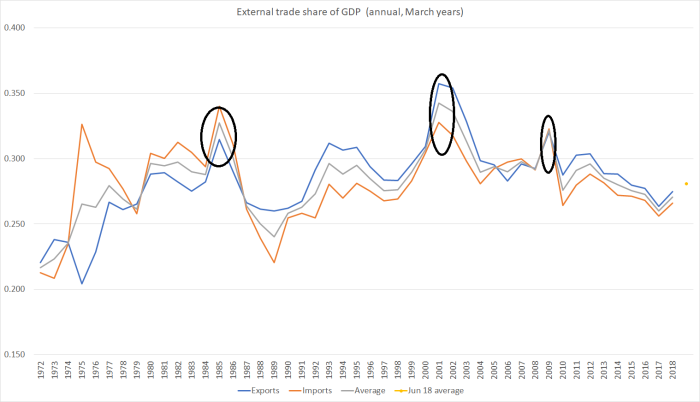

You’d have thought that a senior economics person in our foreign affairs and trade ministry might have thought it worth mentioning that exports as a share of GDP peaked (in modern times) 18 years ago, or that there has been no growth in the real per capita output of the tradables sector in the same period.

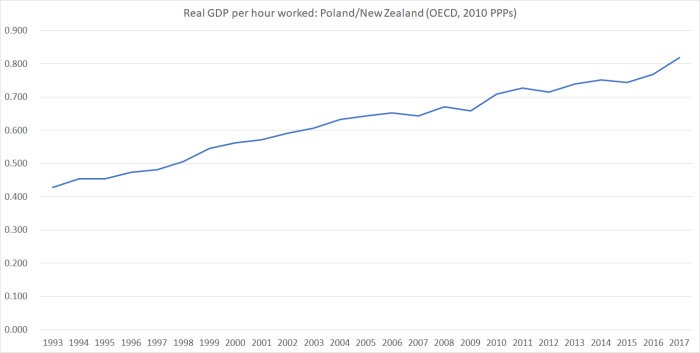

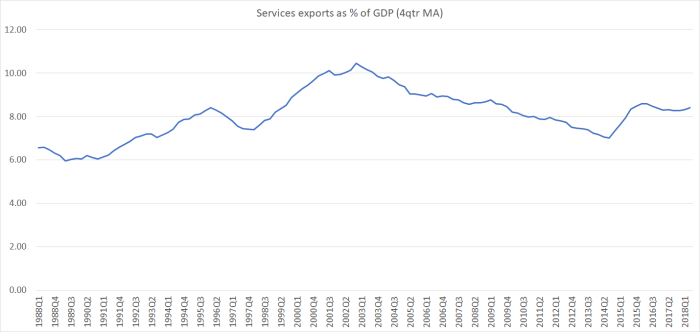

But what about those “weightless exports” specifically? Here is the time series of New Zealand’s services exports for the last 30 years.

The 1990s looked quite good, indeed the peak wasn’t even until as late as 2003, but since then it has mostly been downhill. There was a bit of a pick-up a couple of years ago, but even that doesn’t look to be going anywhere in particular. The services export share of GDP is currently at a level first reached in 1996. This is success?

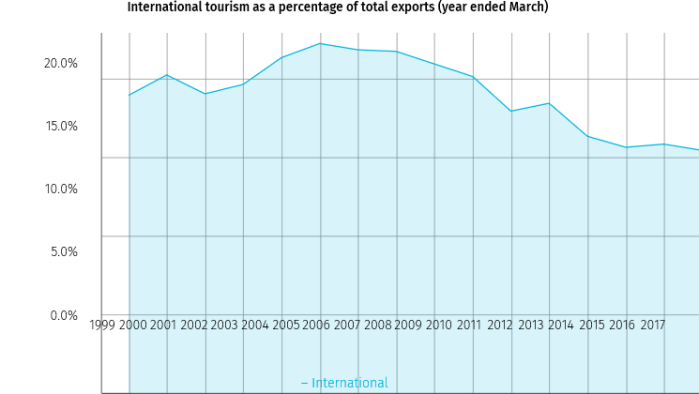

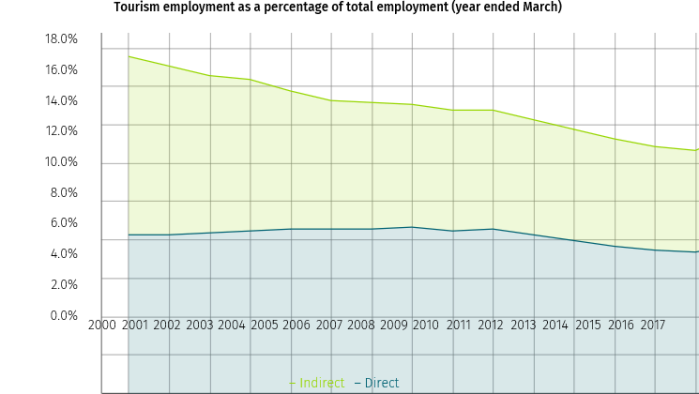

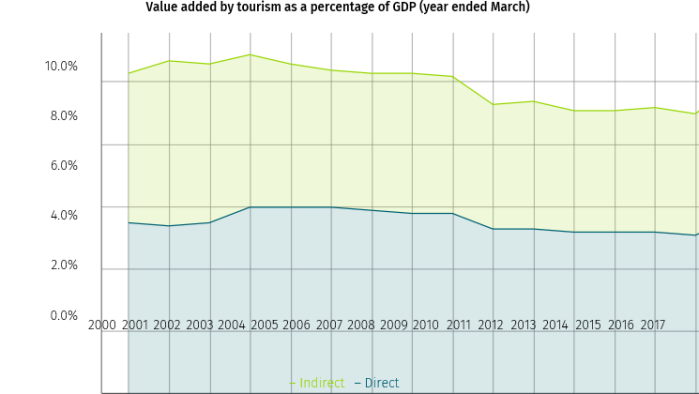

That ANZ chart I started the post with looked quite impressive. Nominal series over long periods of time often do. But MBIE now has a nice tourism data dashboard (there is a migration data one coming), with some useful summary charts. Here are a few of them

and, as a share of GDP – direct and (estimated) indirect contributions

(UPDATE: A careful reader points out that these charts, which I directly downloaded from the dashboard, have not translated correctly. Anyone wanting the correct pictures should go to dashboard itself (link above) and click on the “Overview” menu and then “Economic Contribution”. As represented above the charts don’t capture the pick-up in tourism in the last couple of years.)

And tourism is by far the largest component of our “weightless exports”. We all know there are specific services firms doing well, either selling abroad directly or (as Ms Graham notes) with their services embedded in other goods exports, and on the other hand we have the film industry (kept alive on massive direct public subsidies) and the export education industry (aided by substantial implicit subsidies, bundling immigration and work access provisions to the sale of educational services). The bits that are doing very well, standing on their own feet, just have to be very small relative to the size of the economy, and to the scale of the New Zealand economic challenge (closing those huge productivity gaps).

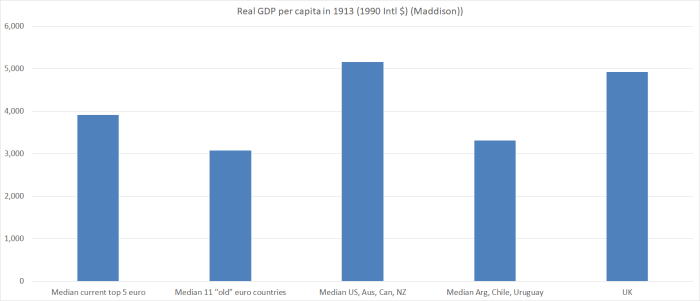

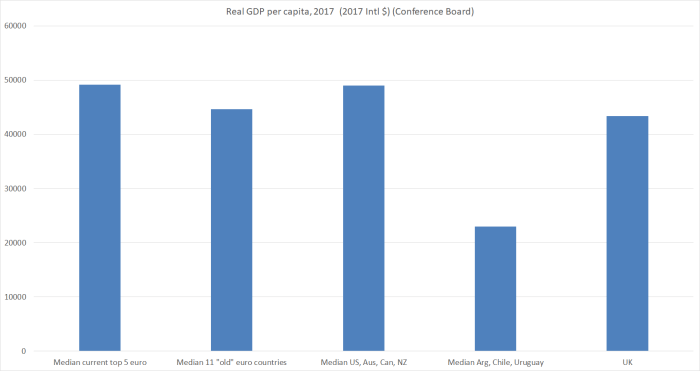

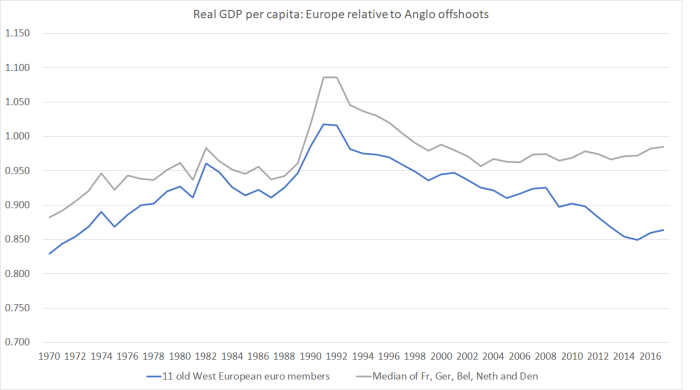

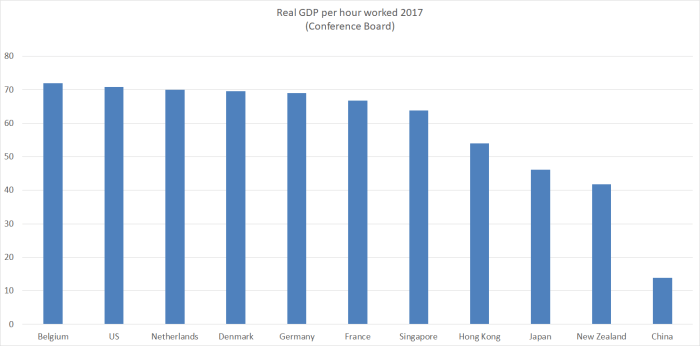

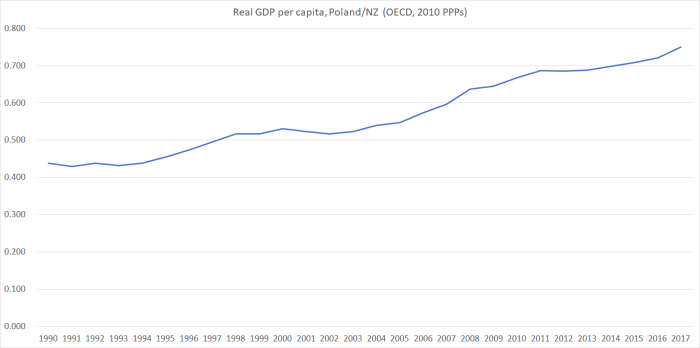

How do we do by international comparison?

Here are exports of services as a share of GDP for the small OECD countries (I’ve left Ireland and Luxembourg off the chart, but – for various reasons – their services export shares are “off the charts” high). Small countries is the relevant comparator here, as countries with large populations naturally tend to have rather lower foreign trade shares.

Services exports from New Zealand have been shrinking as a share of GDP, and our services export share of GDP was low to start with. This century to date, only three of these small OECD countries have had more of a fall in the services exports share of GDP than New Zealand has. And all three of them – Czech Republic, Slovakia and Estonia – have in any case managed much faster productivity growth than New Zealand over that period.

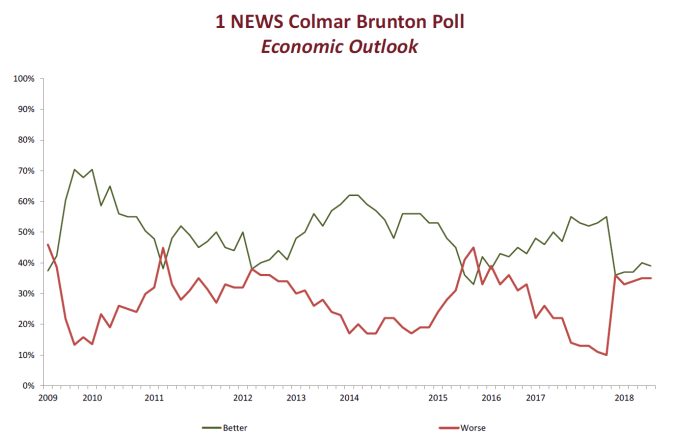

Our economy isn’t doing well, no matter how much bureaucrats and politicians like to pretend otherwise, and regardless of whether one focuses on the “weightless” bit of the economy or the rest of it. We do quite well at employing our people, but then wage rates and productivity are now so modest by advanced country standards – gaps that simply aren’t closing – that more people feel the need to work.

And strangely, it seems that MFAT’s Economic Divisional Manager has some inkling of this as she ends this particular part of her speech thus

I strongly believe that earth will never be “flat”, as Thomas Friedman claimed, and that geography remains, to a greater or lesser extent, destiny. Digitalisation is not causing the end of geography as a key determinant of prosperity. Industry clusters, international connections and trade, knowledge exchange and IP transfer are all positively correlated with geographical proximity as well as prosperity – in other words, they are much easier for large countries and countries with land borders to achieve. The catch-22 for small, isolated countries is that they are also the very conditions essential to overcoming the disadvantage of geographical distance. This is a huge challenge for New Zealand, both in terms of international policy but also domestically – currently we see the government tackling this challenge through regional policies such as the Provincial Growth Fund.

Except that it isn’t some sort of “catch-22”. It is a constraint that New Zealand officials and politicians need to finally get real about. If – natural resource based opportunities aside – the best opportunities in the world arise from being in close proximity to lots of other people (as markets, skills networks or whatever), then trying to grow New Zealand’s population as a matter of policy – lots more people in an unpropitious location – looks crazy. Many of the people who come would have been better off to have gone somewhere else (if they could). And the challenge facing the typical longstanding citizen (native or otherwise) – to manage top-tier global incomes and living standards – is simply made tougher with each new person our governments bring in. That is not because of access to jobs (that is a straw man non-argument – you observe full employment in poor, rich and middling countries) but precisely for the sorts of reasons that Ms Graham of MFAT identifies (even if she apparently has not thought fully through the implications of her observation).