(This is a long post. The short answer is “no”.)

Yesterday I showed that the gap between New Zealand real and nominal interest rates and those in other advanced economies has been large for a long time..

There is quite a bit of debate about why. I want to deal quite quickly with several stories that have been run at times:

- Some argued that high interest rates are mostly down to monetary policy. But even if monetary policy is a bit tight right now, over the last 25 years as a whole inflation has averaged a bit above the midpoint of the successive inflation target ranges. And if the early inflation target was low by international standards, at least since 2002 a target centred on 2 per cent has been very internationally conventional. Monetary policy isn’t the answer. .

- Some have argued that a small country would almost inevitably have higher interest rates (all else equal) than countries with lots of public debt on issue (eg the US, Germany, Japan, or Italy). Perhaps, but in the data any effect of this sort looks to be very small – Sweden has borrowed at much the same rates as the United States, and New Zealand’s bond yields have also been well above those of the typical small, floating exchange rate, advanced country.

- For a while it was suggested that our nominal bond yields were higher than those abroad because people were less confident that low inflation would last than they were in other countries. But there is no external evidence to support the idea. And although we don’t have long time series of inflation indexed bond yields, what data there are suggest that real interest rates here have been well above those in other advanced economies.

These days the main debate is between a story (which I think the Reserve Bank generally agrees with) in which domestic resource pressures explain our interest rates, and one in which high New Zealand interest rates reflect the high level of net international liabilities owed by New Zealand resident entities. Today I want to explain why I find the latter story unpersuasive.

The story goes that international investors look at the stock of debt, worry about the risk that it poses, and charge New Zealand (dollar) borrowers higher interest rates accordingly. There are number of possible lines of argument:

- The direct one just mentioned: high debt means high risk, and lenders charge a premium (just as a bank might charge more to a highly leveraged borrower)

- A story based on incomplete mobility of capital. According to this story, we can borrow a great deal of money at “the world interest rate”, but our high NIIP means we run up against the limits of the number of investors who might be interested in having New Zealand exposures, and the net effect is a higher cost of credit at the margin.

- A story based around exchange rate crisis risk. In this story, it isn’t the debt itself that is necessarily risky (and the evidence is that highly rated NZ USD borrowers haven’t typically paid much more for debt than similar US USD borrowers) but rather NZD-denominated debt, because of the exchange rate risk. Specifically, even if the New Zealand dollar trades pretty normally in normal times, a country with lots of foreign debt is exposed to considerable rollover risk. In times of crisis, the exchange rate could fall a very long way. To compensate themselves for this risk of a NZD foreign exchange crisis, investors demand a higher return on NZD assets than they would on comparable assets issued in the currency of a less indebted country.

In the abstract, these can sound like plausible stories. And there certainly have been cases of countries with very high levels of debt where yields have sky-rocketed, or who have even been cut out of funding markets altogether. The risk of being cut off by funding markets played on the minds of New Zealand policymakers for decades, dating back to the 19th century.

But I don’t think these risk premia stories (which is how I will collectively describe them) can really explain what has gone on in New Zealand in recent decades.

Is there, for example, any sign that investors and offshore lenders have been particularly concerned about New Zealand’s international investment position?

The short answer is “not really”. And that shouldn’t really be surprising. By international standards, the net international investment position of New Zealand is quite large, at around 70 per cent of annual GDP. Historically, it has swung through huge ranges – probably nearer 200 per cent at peak in the late 19th century, and perhaps only around 5-10 per cent of GDP in the early 1970s. The net external liabilities ran up rapidly in the late 1970s and early-mid 1980s. That mostly reflected the very substantial increase in public debt that occurred at the same time. New Zealand’s historical statistics aren’t good, but the points in the previous two sentences aren’t really contentious.

But what is sometimes forgotten is that the net international investment position (as a share of GDP) has now been basically flat for 25 years. Here is the chart, with data as far back as the official SNZ series goes. The NIIP wobbles around a bit, and is a bit lower than usual at present on account of all the reinsurance claims that crystallised following the Canterbury earthquakes, but has not gone anywhere for 25 years.

In itself, that is interesting, because public debt has changed a lot. In the late 1980s, net public debt was large, and one could think of the NIIP position as being largely accounted for by the government’s debt (large operating deficits over too many years, and the Think Big debacle). Foreign lenders might have been a bit worried, and there were some signs of that: the threat of a double downgrade, and Ruth Richardson’s hasty trip to New York to fend off that threat.

But government debt subsequently fell steadily for 15 years, and one year the government even had slightly positive net assets (this is data from the Treasury’s long-term tables). Debt has certainly increased a little over the last few years, but there is no sign from anyone (investors, rating agencies etc) that our public debt is a concern. It isn’t the lowest in the advanced world, but it is towards the lower end of the range.

But as government debt shrank, private borrowing moved in to take its place. By contrast, in Canada when the government got on top of its fiscal problems – impelled in part by a crisis of investor concerns around Quebec – in the mid 1990s, the reduction in public debt was matched by a significant reduction in Canada’s (then) large net international investment liabilities.

The fact that our net international investment position has stayed large and negative, even as the government finances have been put into pretty good shape is one straw in the wind suggest that our interest rates aren’t high because of worried foreign investors. When lenders got worried about the financial health of borrowers, and increase the cost of finance accordingly, rational borrowers tend to wind back their debt. Corporates do it. Households do it. Governments do it. New Zealand didn’t.

The other straw in the wind is that the exchange rate has stayed persistently high. To be sure, it has gone through quite large cycles, and people can debate whether it is “overvalued” or not, but I’m pretty sure I’ve not heard anyone argue that the NZD has been consistently undervalued over the last 25 years. The much more common line has been to note how high the exchange rate has been, and to think that it really needs to go down. That has been a line from the IMF and from domestic officials. And it shows up in things like Cline and Williamson’s fundamental exchange rate estimates, which have consistently suggested that the NZD has been one of the most overvalued currencies in the world.

Academic papers often model the effect of investor concerns by adding a term (a “risk premium”)to the interest rate. They do so largely for reasons for analytical tractability. In fact, overseas investors have no way of adding a premium to New Zealand’s short-term interest rates. The Reserve Bank sets the OCR, based on domestic pressures on local resources. Foreign lenders getting concerned about the level of debt New Zealand entities have doesn’t increase resource pressures. If anything, such concerns might diminish resource pressures a little (eg a bit less greenfields foreign investment).

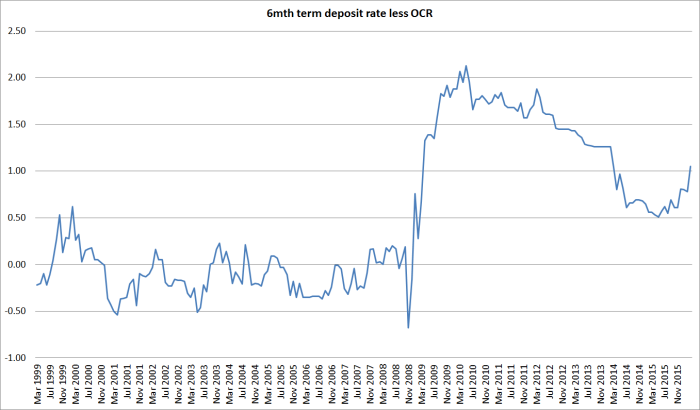

Long-term bond yields are freely traded. We saw that yesterday in the spike in the yields some of the European crisis countries faced in 2011 and 2012. But over 25 years, the gap between New Zealand and foreign long-term interest rates has been less than gap between New Zealand and foreign short-term rates. Again, it doesn’t suggest some unusual risk premium related to the high level of NZ’s external debt.

Of course, the interest rate is not the whole of the foreign investor’s return. A foreign lender buying a New Zealand government bond outright has to think about two factors: the interest rate on the bond, but also the change in the exchange rate between when he purchases the bond and when he finally sells it and repatriates his money. The investor doesn’t know how much the exchange rate will change, but he needs to form an expectation (actual or implicit).

Long-term interest rates are largely determined by expected short-term interest rates, and short-term interest rates are largely determined by domestic pressures on resources. But nothing of that sort anchors the level of the spot exchange rate. Foreign lenders don’t need to purchase, or hold, New Zealand dollar bonds. If they were ever to become particularly concerned about New Zealand they might look to sell, or reduce their purchases, of New Zealand dollar assets. That selling might raise domestic bond yields a little, but it would certainly be expected to lower the exchange rate. In an economy with heightened investor concerns and a floating exchange rate, the exchange rate would be expected to fall to the point where the combination of the interest rate on the domestic bond and the expected future appreciation in the exchange rate together provide sufficient return to cover the investor’s perception of risk[1].

If this all seems a little odd to readers, think of a parallel with equity markets. If investors become concerned about the risks on an individual share or on the market as a whole, they will want a higher return to compensate themselves for that risk. The typical response is not to demand higher dividends (which could be thought of as parallel to a higher interest rate on a debt instrument). Even if corporate boards agreed, higher dividends would be only likely to further weaken the companies’ financial positions. The operating businesses can’t readily usually quickly generate more cash-flow – indeed, if they could the concerns probably would not have arisen in the first place. Instead, what typically happens is that the share price falls (the “equity risk premium” is said to rise). How far do share prices fall? Well ,they need to fall far enough that in combination the dividends and the expected future increase in the share price together provide enough return to investors for them to be comfortable continuing to own the shares.

In a similar way, a country which lenders regarded as having too much debt for comfort, and from which they wanted a higher return, would tend to be a country with a weak exchange rate not a strong one.

As I put it in a paper a couple of years ago:

If sustained heightened external investor concerns about the New Zealand NIIP position had ever developed they would, most probably, have been reflected in a sustained period of exchange rate weakness. And an adjustment of this sort would have been an example of self-stabilising properties of the economy at work. A fall in the exchange rate provides the signal that shifts resources away from meeting domestic demand, towards (net) production for exports. That shift of resources in turn and over time reduces the build-up of net external liabilities, lowering the NIIP/GDP ratio back towards some more comfortable/sustainable/normal level. As the NIIP ratio returns to a more comfortable level, foreign investor concerns should ease expected required returns would fall, and the exchange rate might be expected to recover some ground.

We have seen no sign of that sort of pressure on any sustained basis at any time since at least the early 1990s. If anything, the concern at times was around over-exuberant capital inflows. There is no sign that external investor concerns have driven our interest rate differentials. Instead, it is the domestic pressures on resources, generated by firms, households and governments savings and investment choices that explain most of it.

Of course, persistently high New Zealand interest rates don’t mean there is a free lunch on offer to foreign investors. Recall that an investor’s total return is the interest rate on the New Zealand dollar asset, and the change in the exchange rate. When interest rates here look particularly attractive to foreign investors, the exchange rate tends to rise to the point where the expected future depreciation just offsets the additional returns on the NZD security. The critical word in that sentence is “expected”. Expectations drive behaviour. In New Zealand’s case, a lot of expectations have been consistently misplaced. Over a long period, investors have expected the gap between New Zealand and foreign yields to close. And it hasn’t – not on any sustained basis anyway. And when our interest rates got particularly high, investors have usually expected the exchange rate to depreciate before too long, and invested accordingly. Ex post, people buying and holding New Zealand dollar assets look to received windfall high returns, but in fact they took a great deal of risk to secure them. Had the market’s expectations about interest rate convergence come right, they would have ended up not consistently better off than if they had kept their money at home.

So my argument is that New Zealand interest rates have averaged so much higher than those abroad because of domestic resource pressures. Those on-going pressures have helped keep the NIIP position large (unlike Canada). The nature of those pressures is not that well understood (probably why markets have been persistently surprised). Before too long, I’ll do a post or two looking at some of the factors that might lie behind those surprisingly strong pressures.

In the meantime, I covered this material on pages 42 and 43 of this paper (which also has the references to various papers that make the risk premium case). The paper itself outlines the resource pressure arguments more fully.

But the key point to take away is that stories about investor concerns imply a low exchange rate, perhaps puzzlingly low from a New Zealand perspective, not a high one. Don’t take my word for it – as Charles Engel, one of the leading scholars in the field. put it “a currency whose assets are perceived to be risky….should be weaker ceteris paribus”.

Perhaps we would have seen that sort of pressure in the late 1970s and early 1980s if we had had an open capital account and a floating exchange rate. But we’ve seen nothing of the sort, for any prolonged period, in the last 25 years.

[1] It is different in a fixed exchange rate country (such as the eurozone countries in the 2011/12 crisis) where the pressure must go into domestic interest rates. But New Zealand has long had a floating exchange rate.