The ever-ebullient Minister of Economic Development (and a great deal else beside) Steven Joyce was interviewed on TVNZ’s Q&A programme yesterday, defending the government’s economic record. Despite the efforts of the interviewer to pin him down – including on the rising degree of unease even among some of those one might think of as “elites” about immigration policy – Joyce put up a pretty forceful defence, often citing the Prime Minister’s mantra that if New Zealand has challenges they are ‘quality problems” or “side-effects of success”. If one didn’t have access to the facts, it might even have sounded persuasive.

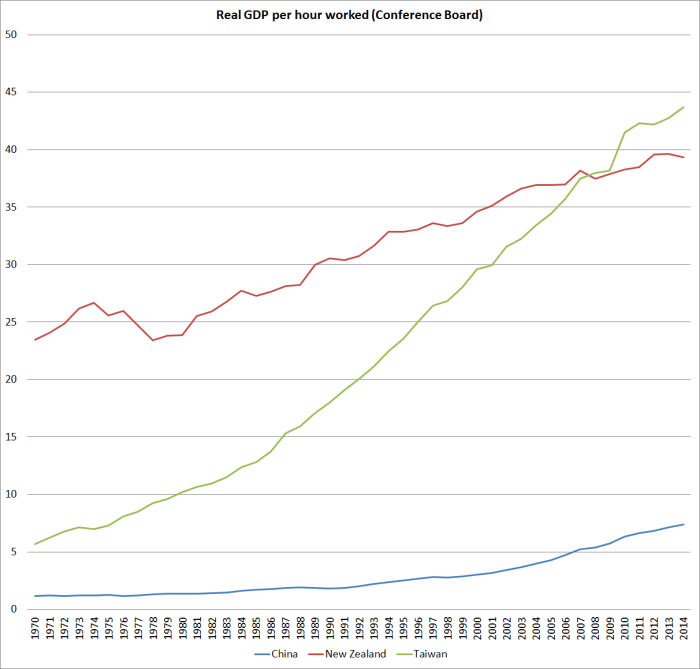

I was tempted to devote a lengthy post to the Minister’s claims, but I have other stuff I really have to finish today. So apart from noting in passing New Zealand’s continuing lousy productivity performance (see the chart in this post), I wanted to focus on just two of the areas the Minister covered.

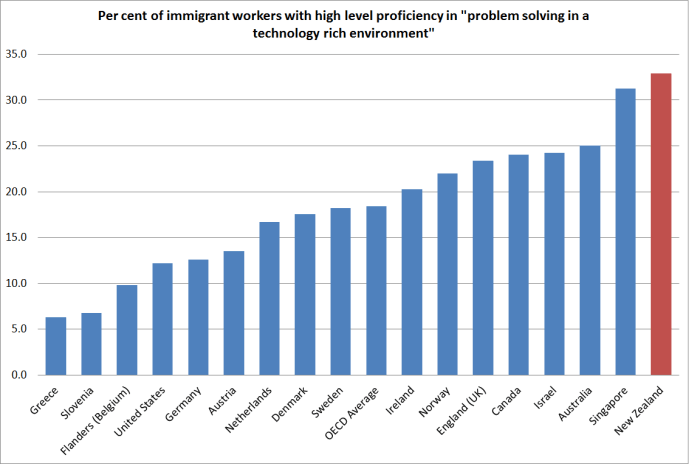

The first was around the skills of immigrants. In June the OECD released the results of a fascinating multi-country study of the skills level of workers. It suggested that the skill levels of New Zealand workers – over several dimensions – were pretty high. I wrote about it at the time, and summarized the high-level findings this way

Looking across the three measures, by my reckoning only Finland, Japan, and perhaps Sweden do better than New Zealand. Perhaps there is something very wrong with the way the survey is done, and it is badly mis-measuring things, but those aren’t usually the OECD’s vices. For the time being, I think we can take it as reasonably solid data.

As I also noted, the survey also looked at the skill levels of non-native born workers. In almost every country, including New Zealand, the skill levels of immigrants were below that of natives. Of course, in every country there will be many very able immigrants, but these are averages across the full samples of native born workers and immigrants. As I pointed out, if your country (New Zealand) already had among the very highest skill levels in the world, and immigrants had less good skills, it didn’t lend much support to the idea that we needed lots and lots of immigration to lift the productivity of New Zealand workers, and make up for deficient skill levels at home.

But none of that stopped Steven Joyce introducing this same report in support of the government’s immigration policy. How did he manage that? Well, he correctly pointed out that New Zealand’s immigration policy is more skills-focused than those of most countries. Unlike most countries, we have almost complete control over who we let in – there isn’t a material illegal immigration problem – and unlike, say, the United States (where legal immigration is mostly family-focused) we have an explicit economic/skills focus. We may not do it well – my argument – but we are less bad, on that score, than most.

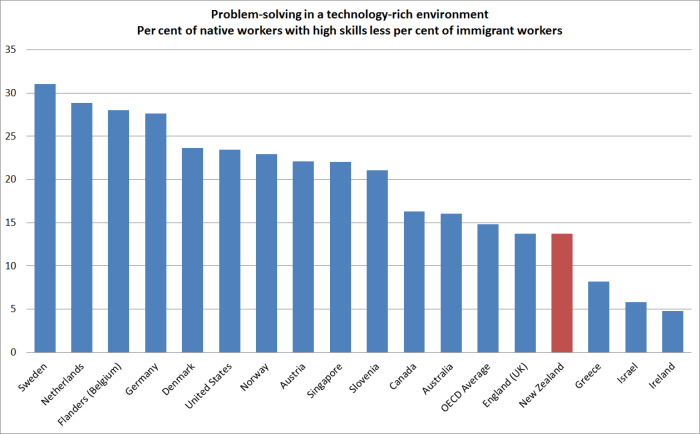

One might reasonably expect literacy skills of immigrant workers to lag behind those of natives – after all, for many/most English isn’t their native language. But the OECD survey also reports results for “problem solving proficiency in a technology-rich environment” (Figure 3.15 of the OECD report). There are 28 countries/regions in the OECD study, but there is only data on the skill levels of immigrant workers for 17 of them (many of the other simply don’t have much immigration).

Here is the proportion of foreign-born workers with what the OECD calls relatively high level skills in this (problem-solving) area.

New Zealand scores well here. Our (really large scale) immigration programme seems to have done better in attracting people with these sorts of skills (and keeping out others) than most other countries have.

But remember that our overall workforce – mostly native-born – also has among the very highest level of skills of any of these countries. On this particular measure, we were top equal with Sweden.

So here is the gap between the skill level of natives and the skill levels of immigrants (again, on this problem solving proficiency measure).

New Zealand doesn’t do too badly – although Israel and Ireland stand out as clearly better – but in every single one of these countries the skill levels of the average immigrant worker are less than those of the average native worker. And this in an area – the use of technology – where the Minister often likes to stress the importance of immigration. We don’t have the problems of Sweden or the Netherlands, but these OECD data – which the Minister himself quoted in support of his policy – just do not support the claim that our immigration programmes have been boosting overall skill levels in New Zealand. If anything, those programmes have been a net drag. As I’ve repeated many times, I’m not suggesting immigration never could boost skill levels – or that there are not many highly-skilled individual immigrants (as there are many highly skilled natives) – but our skills-focused programme, on the scale the government continues to stick to, just isn’t achieving that goal. Perhaps with annual target of 10000 to 15000 non-citizen migrants (per capita, the same sort of rate as the US has) we might do so.

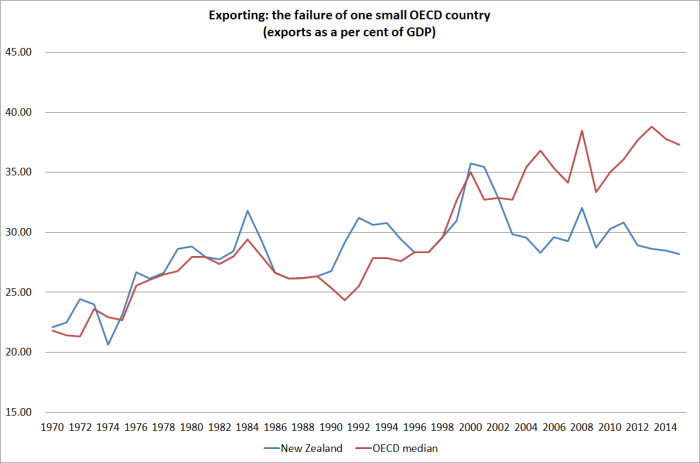

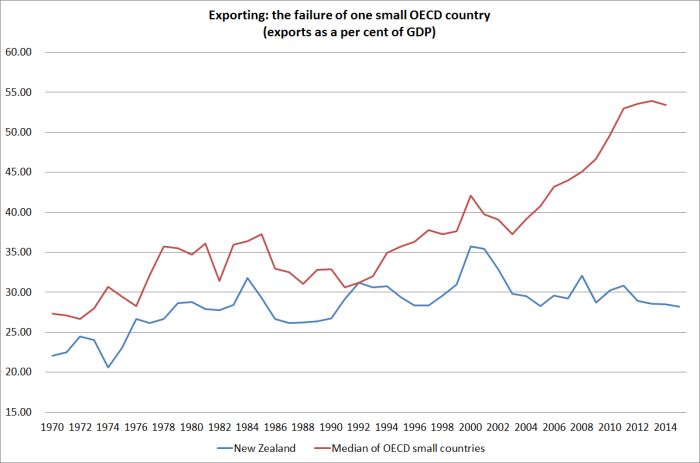

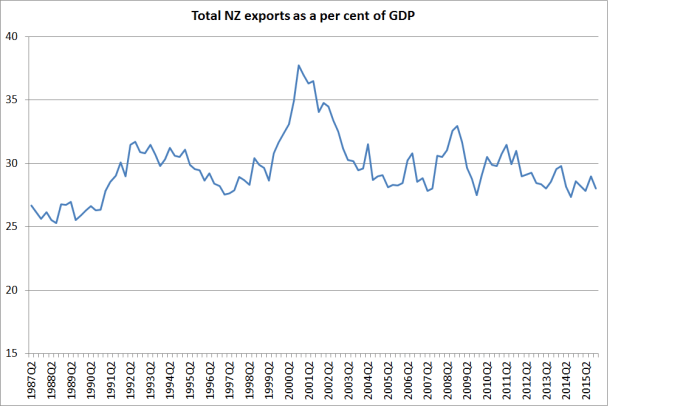

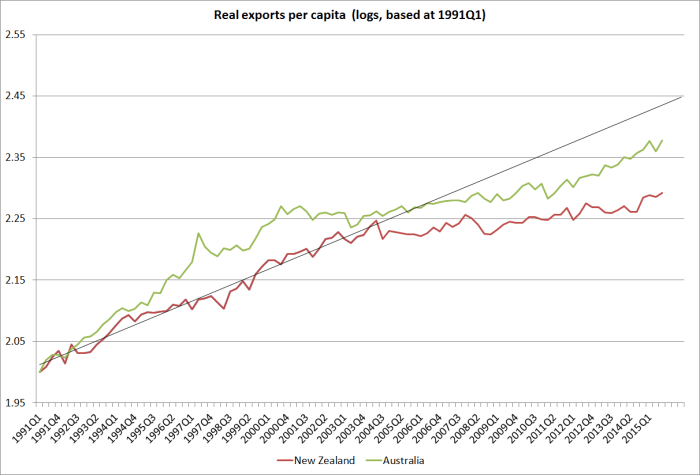

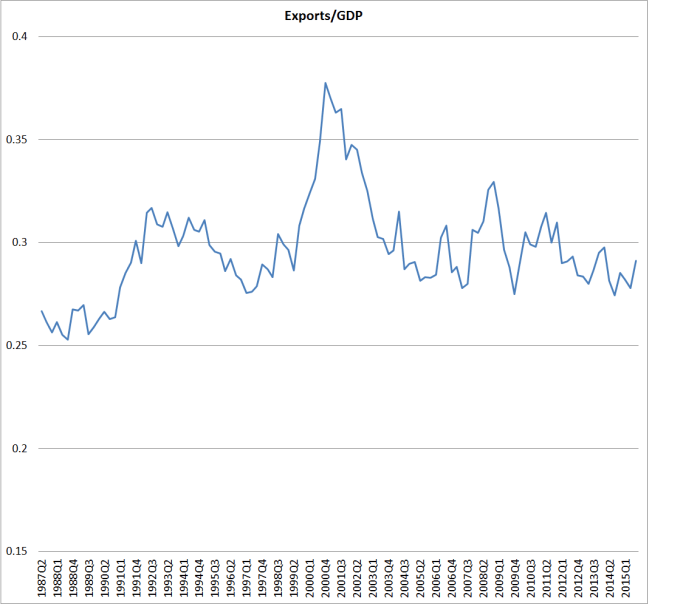

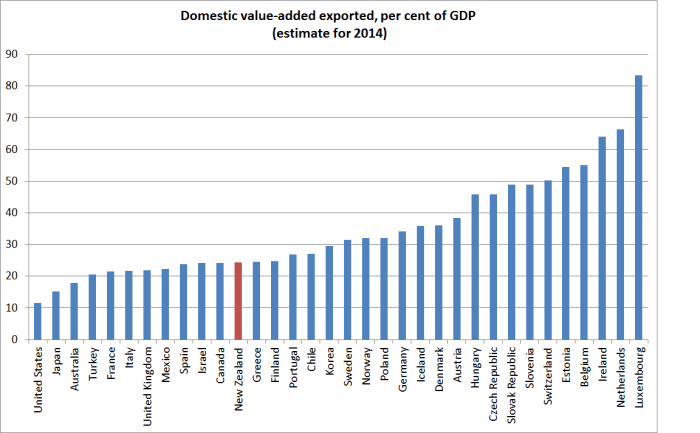

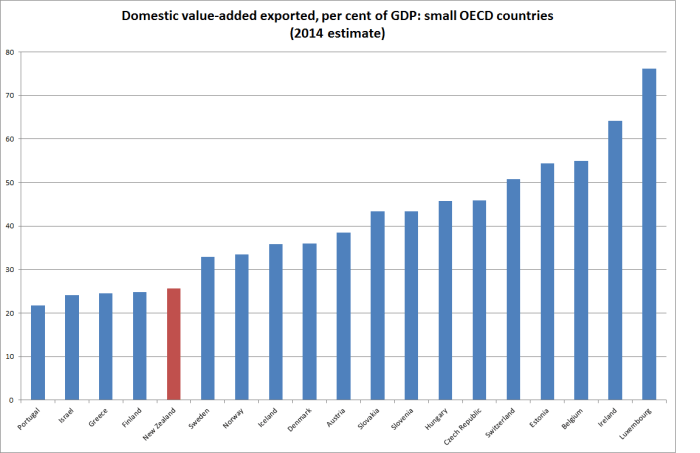

The interviewer also attempted to push the Minister onto the back foot over the government’s target for the share of exports in GDP. The goal, announced several years ago, was to lift exports as a share of GDP from around 30 per cent to around 40 per cent by 2025. I thought the formal target was daft and dangerous, even while sympathizing with the intuition that motivated it – small countries get and stay successful by selling lots of stuff, competitively, in the rest of the world.

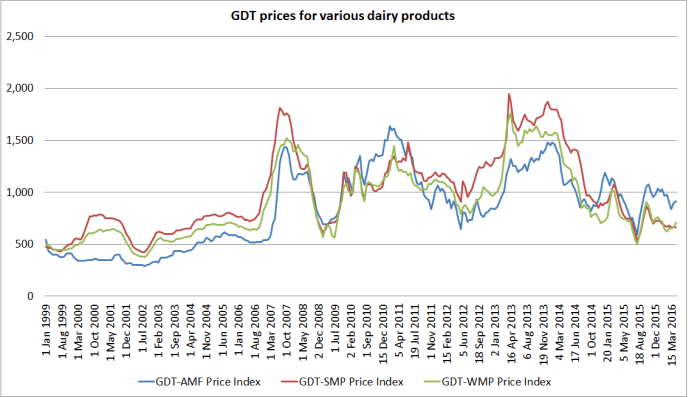

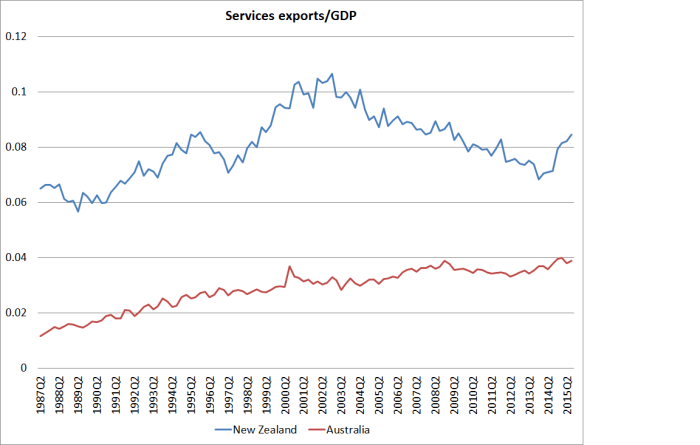

As the Minister fairly noted, the base level of exports got revised in one of SNZ’s long-term national accounts revisions. But that does not change the fact that exports as a share of GDP have been going nowhere. It is all very well to blame low dairy prices – as Mr Joyce sought to – but on other occasions he’d be telling us just how well tourism and export education sectors were doing right now.

Here is chart of exports to GDP, going back to the start of the quarterly national accounts data in 1987. This time, I’ve also shown the average export share for each of the last three governments.

Plenty of things cause fluctuations in the series, and not many of them are under the direct control of governments. Nonetheless, the average export share of GDP is materially lower under this government than it was under the previous government, and the latest observations are below even that average. Since the start of 2009, exports have averaged 27.7 per cent of GDP. Under the previous National government – one that first took office more than 25 years ago, that average was 27.5 per cent. The government’s goal was to lift the export share by 10 full percentage points, and there is now only nine years left until the target date. On performance to date – and policy to date – we might be waiting several more centuries to achieve that sort of goal.

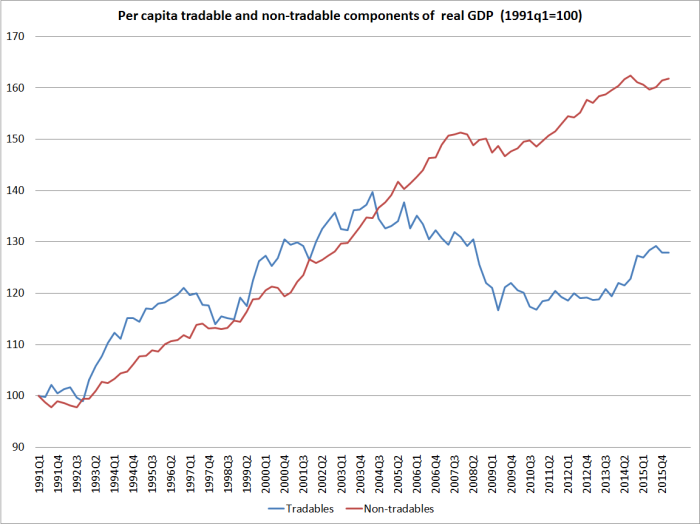

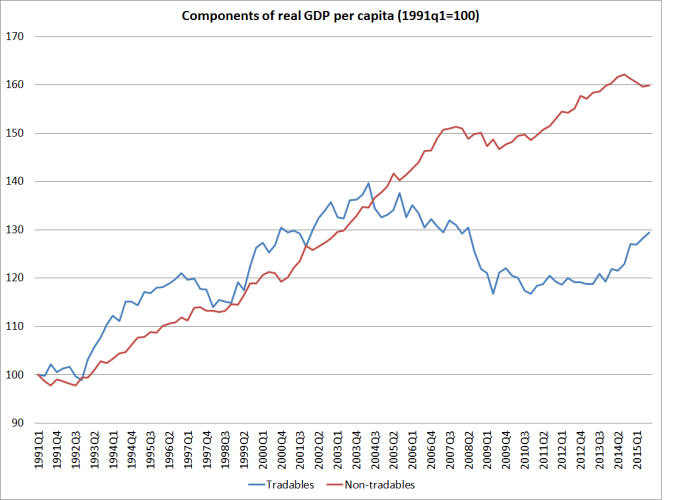

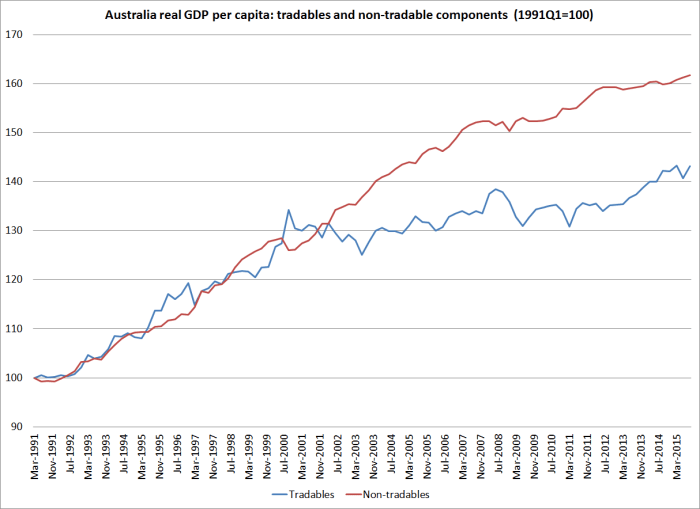

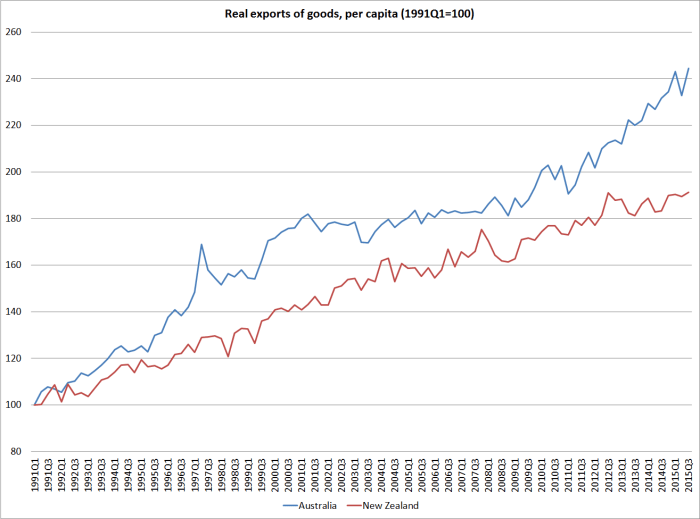

It is time Mr Joyce and his colleagues faced the fact that they are simply failing on this count. A rather different approach is needed – one which permits/facilitates a sustainably lower real exchange rate, orienting the economy more strongly towards investment in the tradables sector, and enabling more able firms to grow (and locate here doing so) by successfully selling to the rest of the world. As I’ve noted before, per capita output in that vital outward-oriented part of the economy hasn’t increased at all for 15 years now. It seems unlikely that that sort of reorientation will occur, all else equal, while we continue to bring in, as a matter of policy, so many not-overly-highly-skilled non-citizen migrants each year.

And finally, the interviewer introduced my name to the discussion as one of those skeptical of some of the government’s claims. Mr Joyce suggested that I was among those who had predicted a large balance of payments blowout, thus apparently undermining the credibility of my arguments. Of course, economists are pretty hopeless forecasters, so when an economist offers a prediction about the future one should (a) always take it with a considerable pinch of salt, and (b) wonder if the economist recognizes his/her own unwarranted over-confidence. But in this particular case, I didn’t even recognize the forecast. Since I’ve spent the last four years – both inside and outside the Reserve Bank – arguing against interest rate increases and for interest rate cuts, it would be surprising if I had been worrying about the current account deficit blowing out. Demand has been consistently weaker than it should have been – inflation has been below target, and unemployment has lingered above the NAIRU. Whatever I’ve warned about, I’m pretty sure it hasn’t been the current account of the balance of payments.

(UPDATE: And, as a reader notes, as banks’ dairy losses mount there will be an almost one-for-one temporary reduction in (mostly foreign-owned) banks’ profits, and thus in the current account deficit. That won’t be a sign of economic success either.)