But that is not what the FTAlphaville blog would have its international readers believe.

It is always interesting when serious foreign media write about New Zealand. Sometimes there are useful perspectives we just don’t see. Then again, when they get things wrong about things you know about, it leaves me wondering about the coverage of things I don’t know so much about.

Yesterday, the Financial Times’s Alphaville blog ran a piece by Matthew Klein headed “What’s bad for Australia is good for New Zealand”. Klein seems interested in New Zealand and has written a few other posts in recent months. In this one he draws on a recent speech by Reserve Bank Assistant Governor, John McDermott, but what is wrong with this post is almost entirely the author’s own work.

He begins with this Reserve Bank chart of the Bank’s estimate of the rate of potential output growth for the last 15 years or so.

Potential output estimates have changed quite a bit as we have moved through time (and actual past estimates have been revised to some extent). The Bank published a useful paper on estimating potential output and the “output gap” a couple of years ago. The biggest single factor explaining fluctuations in potential output growth over time has been swings in population growth – very strong around 2003, very strong over the last year or two, and much more subdued in between. Changes in trend productivity growth also matter, but they are harder to detect. But that slowdown has been real – population growth in the last year or two has been at least as fast as it was in the early 2000s and the Bank’s estimate of potential output growth is much lower than it was then. And as Paul Krugman helpfully reminds if, if productivity isn’t everything, in the long run it is almost everything.

But Matthew Klein seems impressed by those 2.6 per cent potential output growth rates – much stronger than they were a few years ago – and seems unbothered whether that is the result of more people, or of more productive use of people (and other resources). The difference matters.

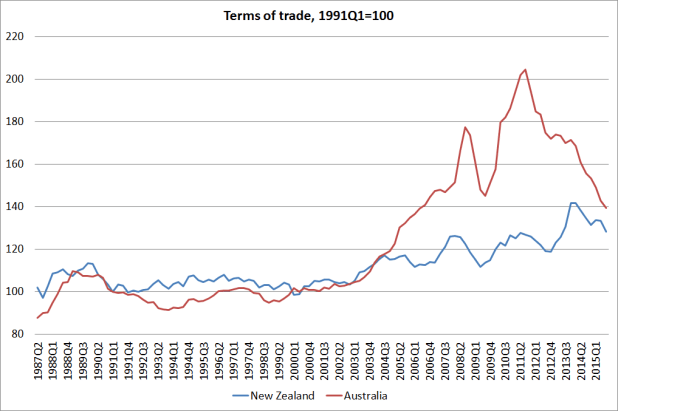

Klein’s story is that the Chinese (demand-driven) hard commodity boom was a terrible thing for New Zealand, and we are now reaping a windfall from the end of that boom.

China’s changing investment strategy has produced a windfall for New Zealand — through the unexpected channel of clobbering the Australian mining sector.

Now I suppose there could be some channels through which the end of that commodity boom might have helped New Zealand and New Zealanders. We import some of those hard commodities too (although of course, we do export some and look what became of Solid Energy). To the extent that slowing Chinese growth might have contributed to lower oil prices, we benefit from that. But these aren’t at all the channels Klein has in mind. On his telling, we have done well because Australia has done badly. And that seems inherently unlikely given that Australia is the largest trading partner for New Zealand businesses, and the largest source of foreign investment in New Zealand.

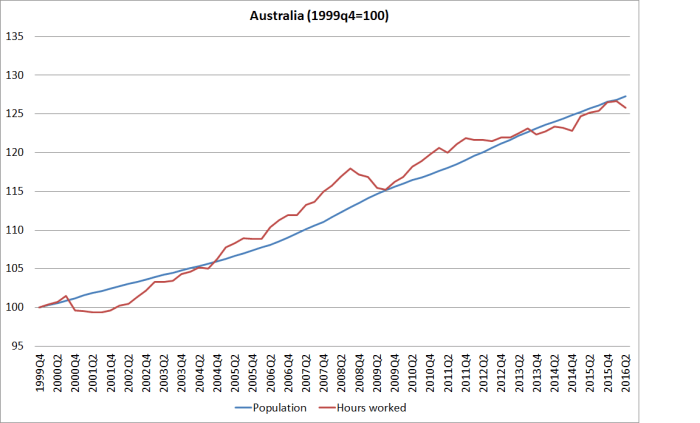

But Klein’s story is one in which New Zealanders fled for greener pastures in Australia when commodity prices boomed, and stopped doing so when commodity prices fell. He runs this chart.

Note that (a) it shows only the flow of New Zealanders to Australia, not the net trans-Tasman flow, and (b) it shows only Australian commodity prices, not the relative Australia/New Zealand prices.

Here is a longer-term chart showing the relationship between the net trans-Tasman migration flow (NZ and Australian citizens) and the relative terms of trade (Australia’s divided by New Zealand’s).

Over decades there have been big cyclical fluctuations in the net migration flow across the Tasman. Allowing for the fact that our population is much larger now than it was, say, 25 years ago, the peaks and troughs don’t seem to have become larger than they were. And most of the time, there haven’t been big changes in relative commodity prices to explain the migration fluctuations.

Generally, a better story explaining the trans-Tasman flows over recent decades would seem to be:

- in typical years there is a fairly large net outflow from New Zealand to Australia (material living standards are simply higher there),

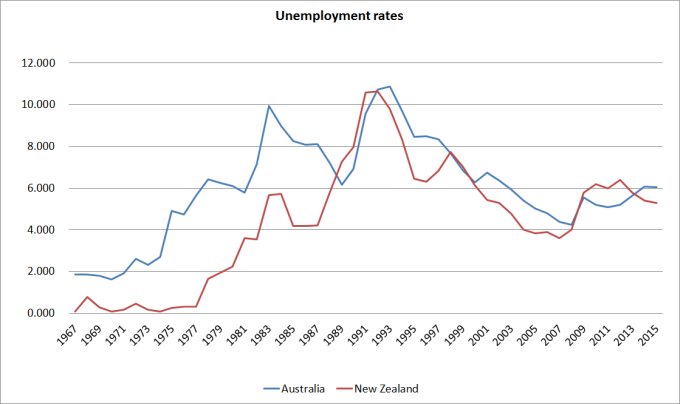

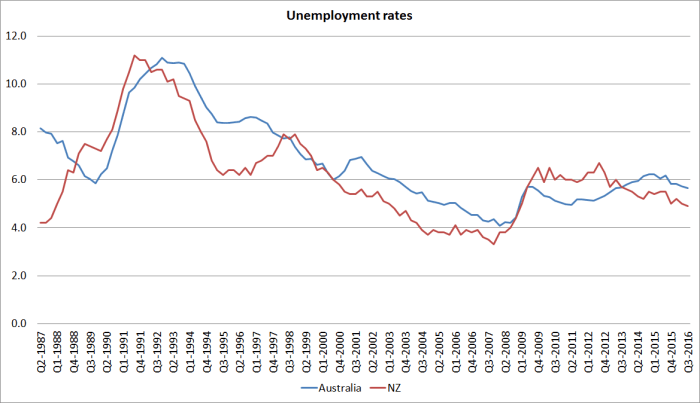

- when unemployment rates in Australia are very low, the outflow is higher than usual, even if unemployment is low here (job search across the Tasman is easier than usual, and those wages are higher). In 2007/08, for example, the unemployment rate in Australia was the lowest in decades, as it was in New Zealand, and New Zealanders still seized their opportunities,

- when unemployment rates in Australia is very high that net flow dries up – people are reluctant to leave existing jobs when the job search across the Tasman is likely to be longer and costlier (as we saw in 1991),

- and when Australia’s unemployment rate is lower than New Zealand’s – which doesn’t happen often – it again makes it very attractive for New Zealanders to go, especially if New Zealand’s unemployment rate is still on the high side. The largest such gap in the last couple of decades was 2010 to 2012, which saw large scale outflows of New Zealanders resume.

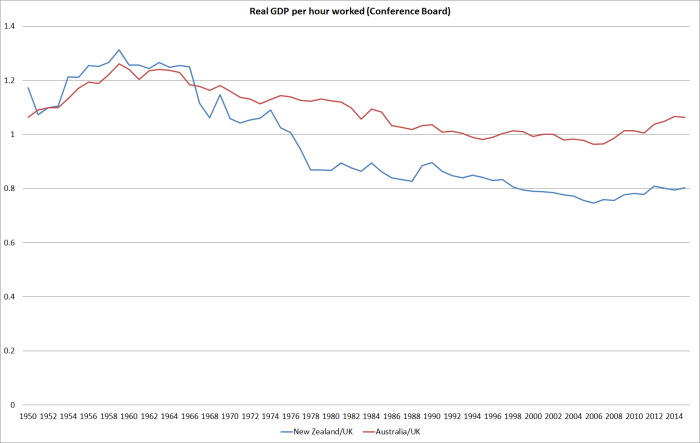

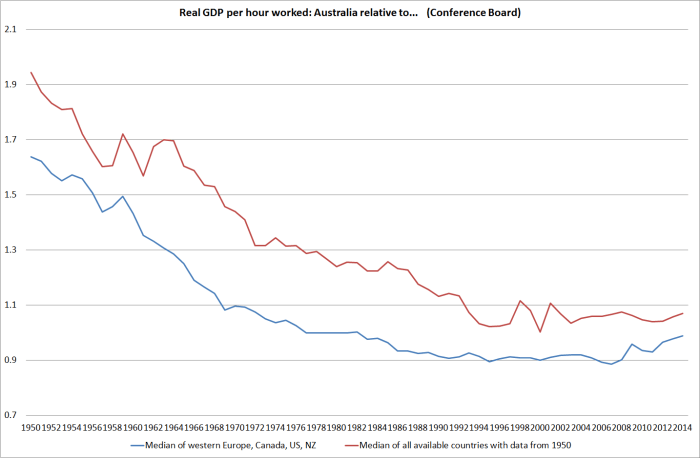

Since then, of course, the unemployment rate in Australia has risen, and that in New Zealand has fallen. In both countries, unemployment is uncomfortably high, and above the respective estimated NAIRUs. Perhaps it is a little surprising that the net outflow of New Zealanders has, for now, come back to around zero, but there has also been a lot more publicity in recent years about the relatively insecure position New Zealanders can find themselves in in Australia if things don’t go well. But it would still be surprising if when both countries have unemployment rates are back at the respective NAIRUs there wasn’t typically a large net outflow of New Zealanders resuming. After all, there has been no progress at all in closing the productivity gaps.

No doubt the hard commodity boom, and associated domestic investment boom, did contribute to the relatively low unemployment rate in Australia over 2010 to 2012. But macro policy (especially monetary policy) also plays a big part in deviations of the unemployment rate from the level the underlying regulatory settings might deliver (the NAIRU). In New Zealand, for example, the inflation outcomes quite clearly illustrate the monetary policy was tighter than it needed to be over that period. Some of that was only clear in hindsight, and the earthquakes also muddied the water, but we didn’t simply have to live with such a high unemployment rate for so many years (which reinforced the incentive for New Zealanders to leave).

But, to stand back, perhaps the more important question to ask is why Klein thinks New Zealand is better off simply because the net outflow to Australia has temporarily ended.

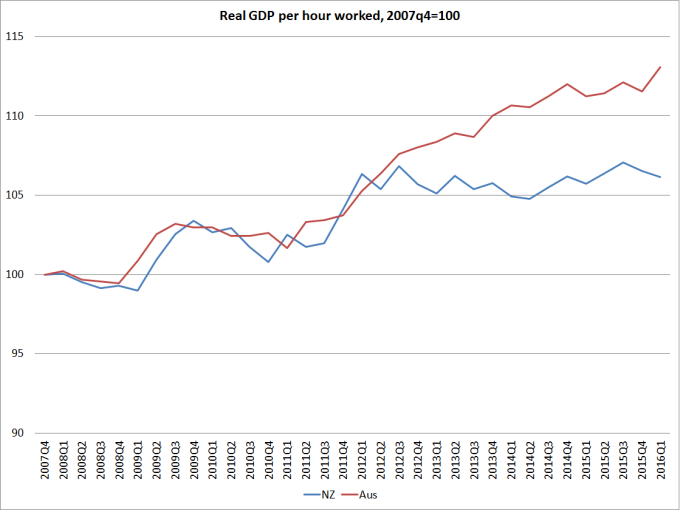

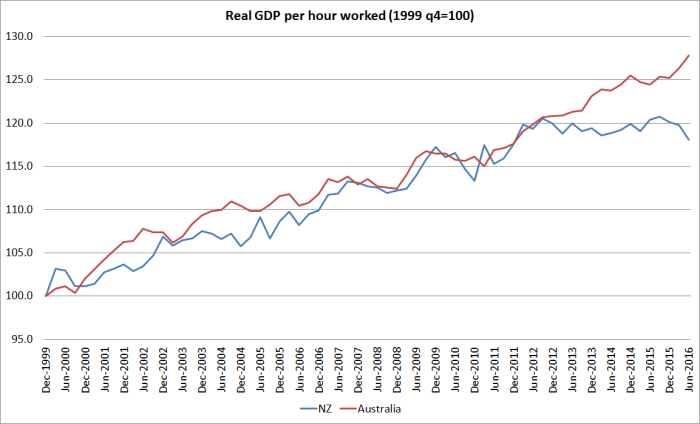

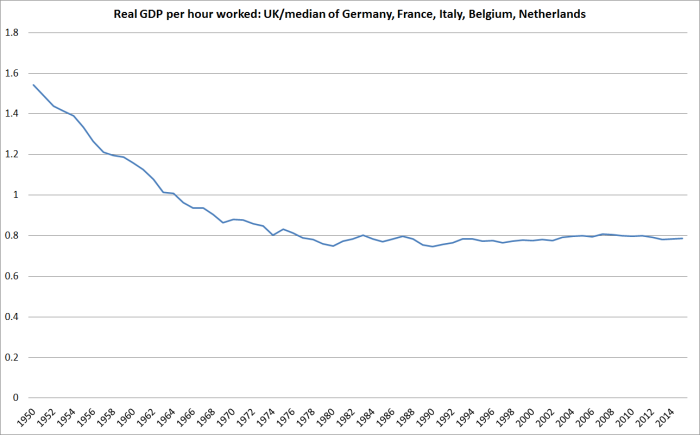

After all, New Zealanders going to Australia presumably do so because they think the opportunities are better there (and most objective measures of material living standards suggest they are right). If opportunities deteriorate in Australia – cyclically or structurally – that isn’t a gain for New Zealanders, but a loss. Fewer of them are, for now, able to take advantage of the opportunities across the Tasman. It would be different if there were New Zealand specific positive productivity or terms of trade shocks that meant that prospects here were improving faster than they had been previously. But there is just no sign of that: as just one indicator, there has been no growth at all in real GDP per hour worked in New Zealand for around four years.

Of course, it might count as a gain if there was some sort of community goal to simply increase New Zealand’s population as fast as possible. One sees those sorts of arguments in various countries from time to time – there was a particularly daft Canadian example the other day – but unless New Zealand is gearing up to defend itself from a military invasion from Antartica, the only good case for pursuing a larger population is if doing so makes us economically better off (higher productivity and all that). And there is simply no evidence it has, or does – whether in past decades, or in the latest population surge.

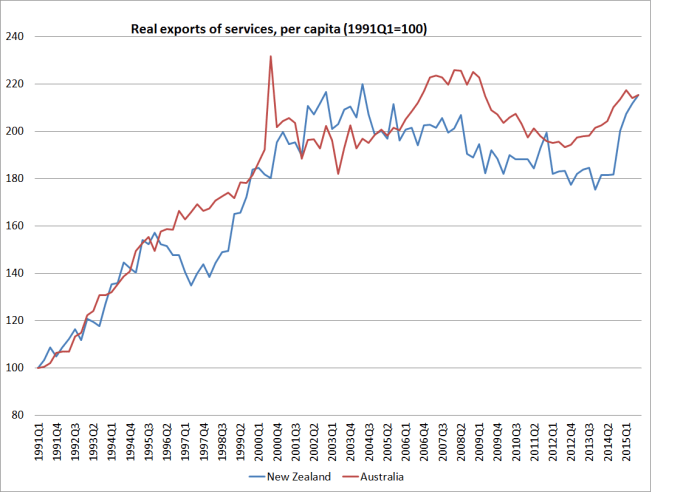

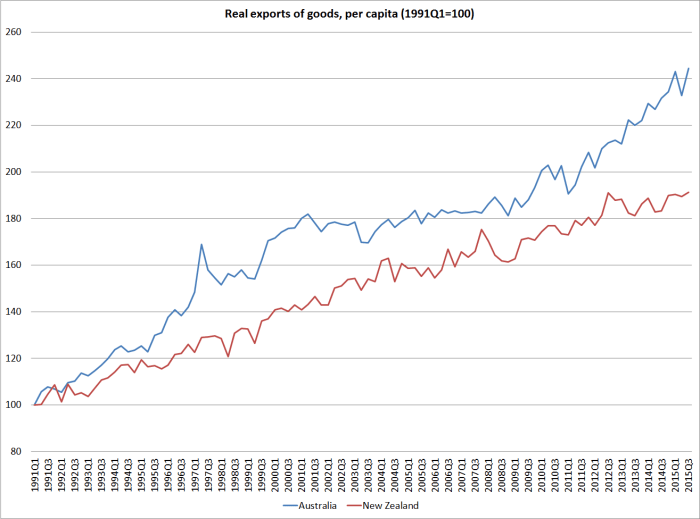

And all this is before reverting to the point that New Zealand firms trade more with Australian firms and households than they do with those in any other country. Australia is New Zealand’s biggest export market. And so when Australian income growth tails off rapidly, as it has in the last few years, it isn’t very propitious for New Zealand firms hoping to increase their sales in Australia. Weaker income growth in target markets is generally thought to be bad for the sellers (and their country) not good.

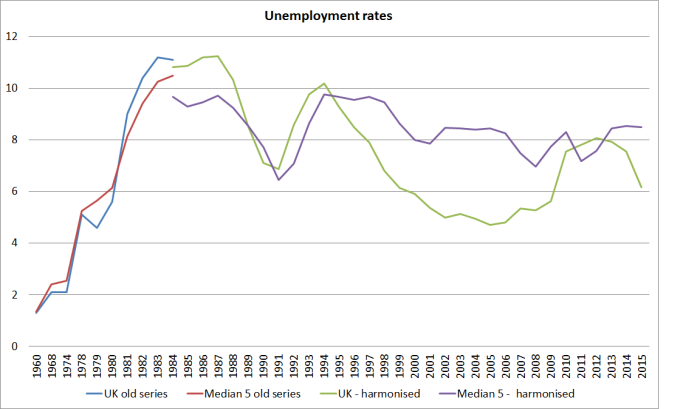

Here is a chart showing the net migration outflows for a longer period.

I’ve shown a variety of measures of trans-Tasman flows, and one of all NZ citizen flows everywhere. They are all highly-correlated, as trans-Tasman flows almost always dominate the overall movements of New Zealand citizens. There have been three times in the nearly 40 years for which the citizenship data have been available when the net outflow of New Zealanders has temporarily abated:

- around 1983, when Australia was in recession and its unemployment rate was over 10 per cent,

- in 1991, when both countries had a severe recession and both countries’ unemployment rates peaked around 11 per cent,

- and in the last couple of years. It is unusual in that neither country has been in recession, but both countries have had unemployment rates above the respective NAIRUs, in both countries income growth is much weaker than it was (particularly so in Australia) and in both countries (as in much of the advanced world) productivity growth has disappointed (most especially in New Zealand).

Not one of those occasions could be considered good news stories for New Zealand or New Zealanders. Over the last 40 years, net outflows of New Zealanders to Australia have been something of a release valve – Australia gave them opportunities New Zealand could no longer provide. Unless and until New Zealand really begins to turn itself around structurally, anything that disrupts that outflow is more likely to be bad for New Zealanders than good.

Klein concludes his piece thus

As long as New Zealand is capable of boosting domestic spending without relying too much on household borrowing, admittedly a nontrivial challenge, this puts the country in an enviable position compared to much of the rest of the rich world. Policymakers should enjoy it while they can.

Given that household credit has been growing at almost 9 per cent in the last year, mostly reflecting very rapid increases in already high house prices, and that there has been no productivity growth for years, all while the unemployment rate has lingered above the NAIRU, I’m not at all sure what Klein thinks policymakers should be enjoying. Perhaps write-ups like his – while they last – but there doesn’t seem to have been much in the story for New Zealanders in recent years.

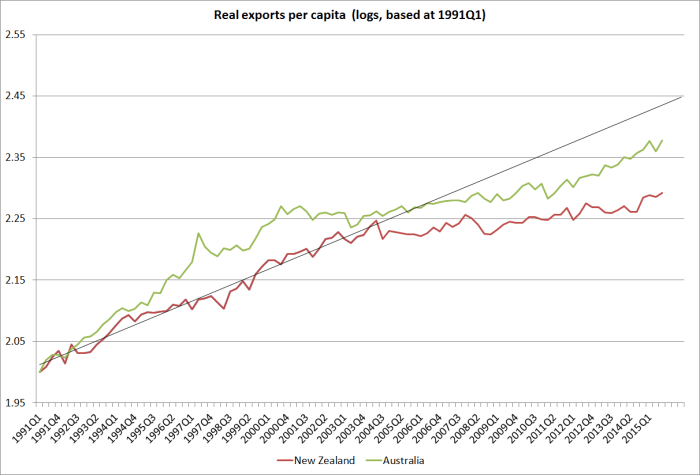

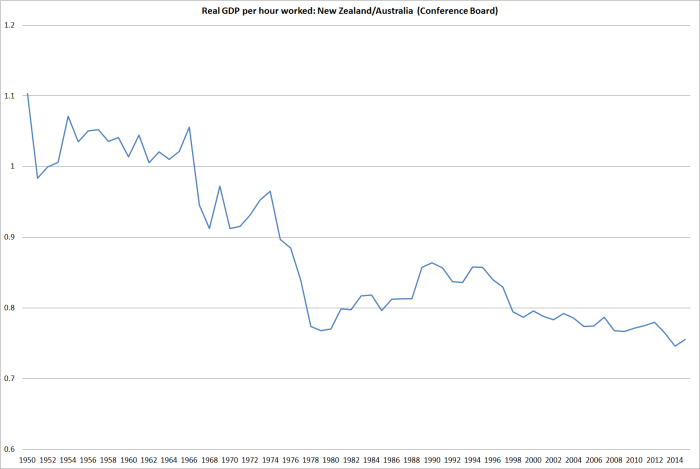

Here is the productivity growth comparison with Australia. If anything, the latest relative deterioration seems to coincide with the end of the Australian commodities boom. I doubt that relationship is really causal, but it certainly doesn’t seem to help Klein’s story.

In general, what is good for the economy of our largest trade and investment partner will, almost always, be good for New Zealanders too. That is how trade, and open markets, work.

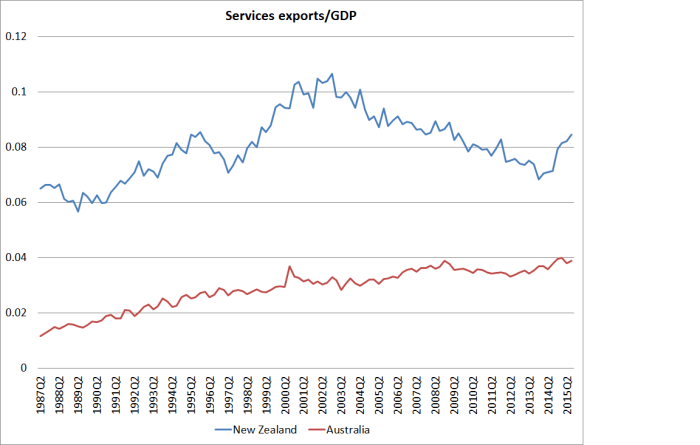

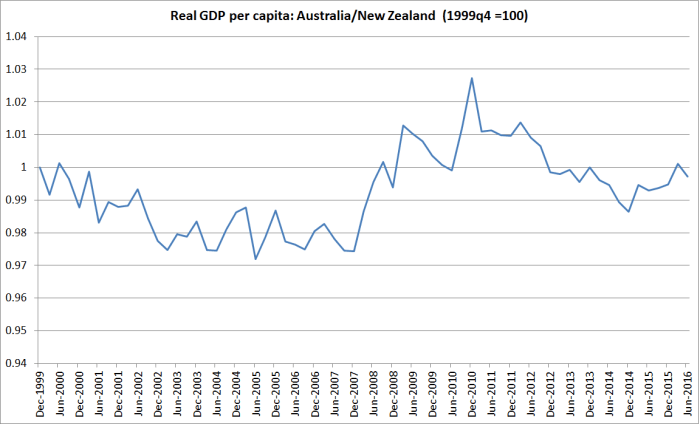

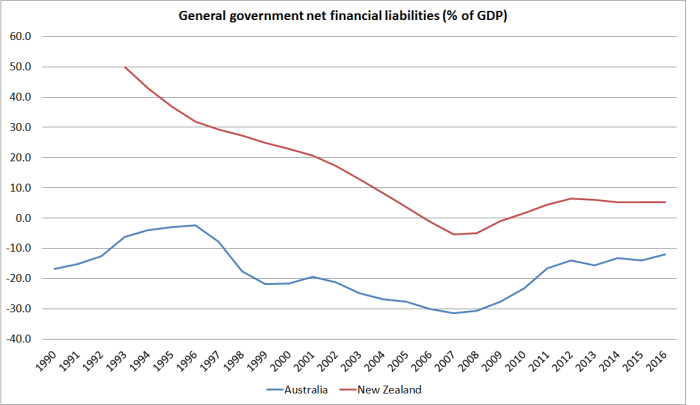

Almost indistinguishable not just now, but over most of the last 20 years. I’m not sure I’m totally convinced, but that is the OECD’s read. Again, nothing that particularly stands out to the credit of English/Key relative to Australia.

Almost indistinguishable not just now, but over most of the last 20 years. I’m not sure I’m totally convinced, but that is the OECD’s read. Again, nothing that particularly stands out to the credit of English/Key relative to Australia.

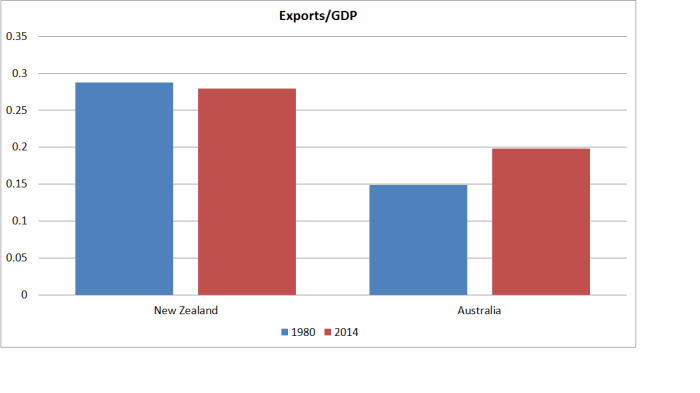

New Zealand’s export share of GDP hasn’t changed in 35 years.

New Zealand’s export share of GDP hasn’t changed in 35 years.