This coming Sunday will be the 40th anniversary of the 1984 election, which ushered in a decade of radical economic reform in New Zealand. The Listener magazine has a cover story (or set of them) on “Rogernomics and how it continues to shape our lives”. The first article is by Danyl McLauchlan (and isn’t bad in itself, even if it could have done with some economic policy fact-checking in a few places), which the contents page introduced with the description that the accelerated reform programme was a “momentous shift in direction for a country on the brink of bankruptcy”. The only problem with that story is that it simply wasn’t so. For decades, people from left and right have run the line, seemingly in need of a foundation myth (on the left for why their beloved Labour did so much dreadful stuff, and on the right to accentuate the case for the far-reaching reform programme, often with a subtext of “see, there really was no alternative”), but the apparent felt need for such a myth doesn’t change the underlying facts. Neither the New Zealand government, nor wider New Zealand (whatever that might mean in this context) was anywhere near the “brink of bankruptcy” in July 1984.

There was, incidentally, a time when the New Zealand government could fairly be described as having been “on the brink of bankruptcy”. The New Zealand government went into the Great Depression with government debt of around 160 per cent of GDP, the subsequent sharp fall in real and nominal GDP drove that ratio well over 200 per cent at peak, and in 1933 there was a default (most countries defaulted in those years, simply never repaying some of their prior legal debt commitments). One could argue that, for different reasons, the New Zealand government was also in deep financial strife in 1939. But it wasn’t in mid 1984.

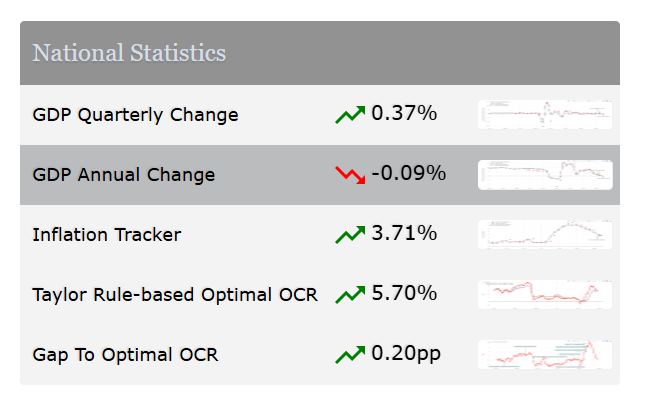

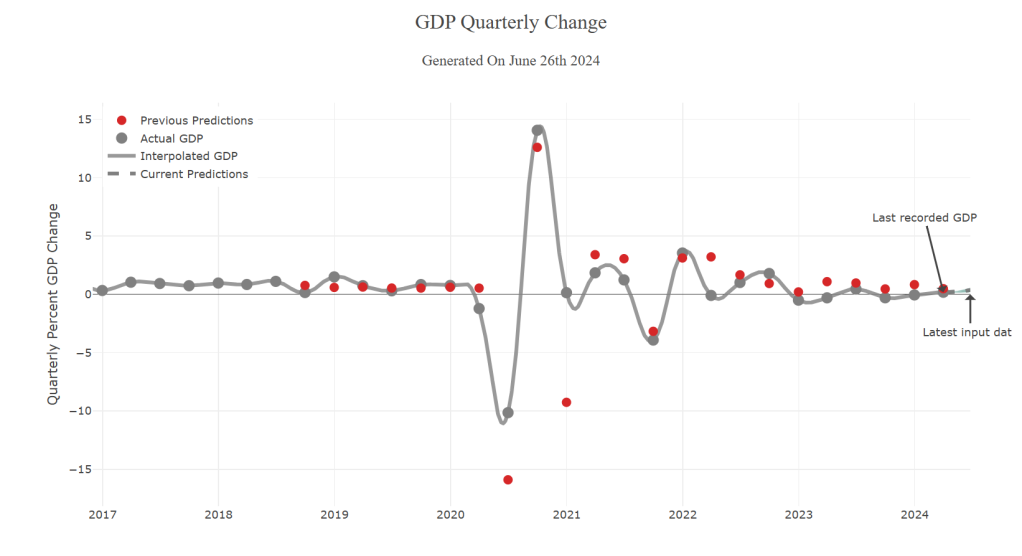

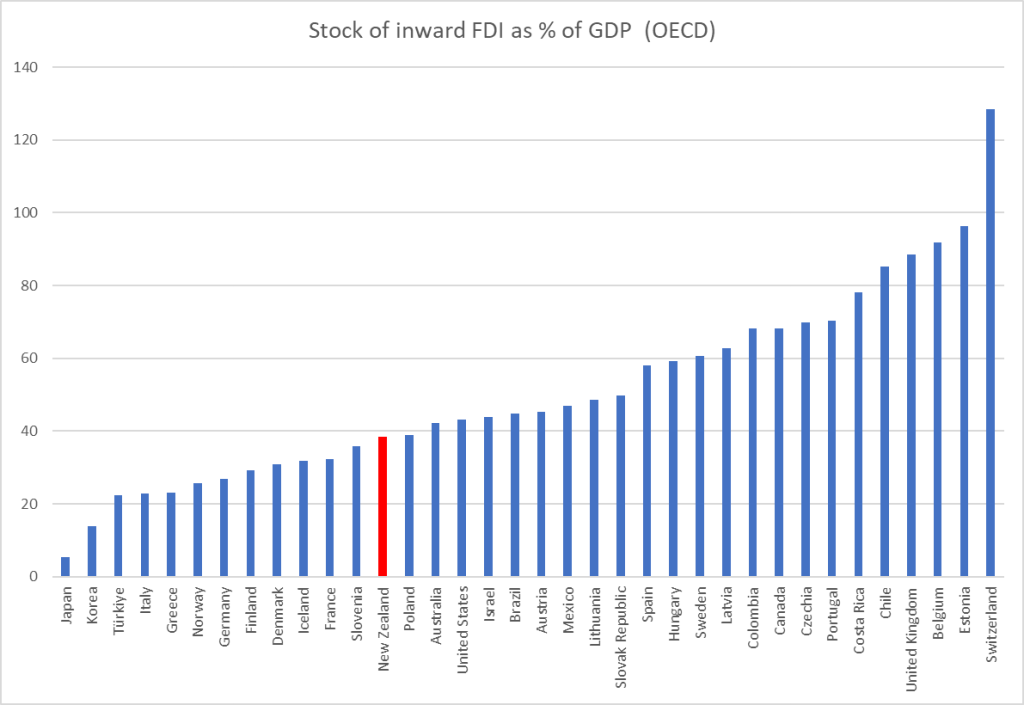

The long-term Treasury fiscal tables only go back as far as the year to March 1972. Even then, changes in accounting practices etc mean the data aren’t fully consistent over time. But this chart captures what there is, up to the current (24/25) financial year forecasts.

As at 31 March 1984 net debt was 29.6 per cent of GDP. On the current preferred measure (including NZSF assets), central government net debt is projected to be 23.1 per cent of GDP at the end of the 24/25 financial year (and lest there be any doubt the New Zealand government is also now not on the “brink of bankruptcy”). Had the debt been increasing quite a bit over the decade running up to 1984? Certainly it had, but nowhere near as fast as many vaguely familiar with the fiscal situation then might have supposed because of the combination of inflation and financial repression (holding interest rates artificially low). Things were a mess, but solvency simply wasn’t the issue.

Finding comparable data for other advanced countries back that far is a challenge, but looking at the OECD’s patchy tables three countries showed up with much higher net debt than New Zealand back then: Belgium, Italy, and Israel (which also happen to be the three I remember being commented on most often back in the 80s). Italy was the least bad of those three back then, but with net debt ratios twice those of New Zealand.

Now, it is fair to add that the official debt numbers back in the mid 1980s didn’t necessarily capture everything. The Think Big projects were being put in place, and if the government wasn’t always a direct financier, protective barriers accomplished similar effects. The reforming Labour government eventually took a lot of that project debt back onto the Crown balance sheet, but as you can see from the chart above even at peak several years later, after a post-liberalisation financial crisis and several years of difficult economic adjustment net debt still peaked at not much more than 50 per cent of GDP. Not good (at all) but simply not then “on the brink of bankruptcy” either (about half of the advanced countries today have net debt in excess of 50 per cent of GDP – IMF data).

Things were certainly in something of a mess in mid-1984. We were just emerging from the wage and price freeze (the price freeze had been lifted earlier that year) and the big uncertainty was how things were going to unfold: would inflation stay moderately low (even the IMF noted at the time that the freeze had gone better than expected) or race back up to 15 per cent? And both the headline fiscal and balance of payments current account deficits were large.

Then again, some context is in order. Inflation really messes up the interpretation of some of these flow balance measures (something the Reserve Bank was publishing a lot of work on at the time), because a big chunk of nominal interest payments are inflation compensation and really, in economic effect, principal repayments. And when international observers really worry about countries’ fiscal policies they often pay a lot of attention to the primary balance (ie excluding finance costs). If a country is running primary surpluses, no matter how small, the debt (and debt to GDP ratios) are most unlikely to explode (in ways that really would raise real solvency/”brink of bankruptcy” issues).

So what do those long-term Treasury tables show? Coming all the way up to the current (24/25) year, we have 54 years of data. In 14 of those years (including 24/25 and the five previous years) the government is/was running a primary deficit. Only three of those years were in the 20th century. One was the year to March 1984, when the primary deficit looks to have been about 0.6 per cent of GDP. Not good (at all), but then this year’s primary deficit is projected to be a touch under 1 per cent of GDP.

The New Zealand was not then (and is not now) on “the brink of bankruptcy”. Here it is perhaps worth noting the IMF’s 1984 Article IV review report on New Zealand, which was finalised in February 1984. In those days, IMF reports were not published and were much more free and frank (this one was leaked to the New Zealand media just prior to the 1984 election, presumably by someone in the RB or Treasury): remarkably, although there is a great of angst about flow fiscal deficits (although with no sense of “brink if bankruptcy” debt stock stuff), there was no discussion of primary deficits at all.

Was the New Zealand economy performing well in 1984? No, of course it wasn’t. It was a mess in many respects, with a great deal of uncertainty, significant imbalances, and lousy productivity growth. But it also wasn’t as if nothing had changed for decades. Liberalisation had been proceeding, at times fitfully and with reversals but the direction was still pretty clear (something recognised in both IMF and OECD reports at the time). The CER agreement with Australia had come into effect just the previous year, formal current account convertibility for foreign exchange transactions had been adopted in 1982, and just a few months earlier auctioning of government bonds (rather than administratively set rates) had commenced (even if it too proceeded in fits and starts). The exchange rate had been fixed since mid 1982, although adjusted once in 1983 when Australia devalued, and the 1984 IMF report notes that it was thought most likely that the crawling peg adjustment model would resume as New Zealand emerged from the freeze. There was a strong sense among advisers of a really overdue need for better macro-stabilisation policies and microeconomic liberalisation policies but no imminent sense of crisis.

There was strong sense (including explicitly by the IMF in that February 1984 report) that the real exchange rate was probably overvalued (not only were there large current account deficits and a really adverse terms of trade, but fixing the nominal exchange rate over the previous couple of years was tending to appreciate the real exchange rate. But it had been a case argued for years.

What changed was when Sir Robert Muldoon called the election and market participants were convinced that (a) there was a high probability of Labour winning, and (b) that if they did win, it was highly likely that Labour would devalue. Roger Douglas was understood to be in favour of a devaluation, and documents that found their way into the public domain only reinforced that sense (as did rumours that a senior Labour MP had told – or strongly implied to – one significant lobby group that Labour would devalue). It was, after all, conventional economic wisdom, not in itself particularly radical.

Intense pressure on New Zealand’s fairly modest liquid foreign exchange reserves began almost instantly (and here the word “liquid” has salience, as some of the funds notionally held as foreign exchange reserves were actually kept by The Treasury in rather illiquid form). These were the days before open and unrestricted short-term capital flows, but even without that possibility, any rational exporter would seek to hold proceeds offshore for as long as possible, while any rational importer would look to make payments as soon as possible. Even just those timing effects, and there were some capital flows too, were enough to create huge pressure. The immediate cash-flow pressure was eased by the Reserve Bank offering (relatively cheap) forward cover, but that didn’t change the basic pressure.

Runs on fixed exchange rates are very hard to stop. They usually don’t start out of the blue, as this one didn’t, and can usually only be stopped if there is a universal commitment – very strongly shared across elite and political circles – not to adjust the rate. Of course, limitless reserves help a lot – including in reducing the chances of runs starting – but in those decades few countries with fixed exchange rates held very high levels of foreign reserves. Interest rate adjustments can help, at least in principle. If liquidity conditions tighten sharply and interest rates rise a lot as a run gets underway it can prompt some people to rethink. In June/July 1984 the Reserve Bank and Treasury advised Muldoon to lift the wholesale interest rates controls and allow some of those effects to work. But even had he been so minded it probably wouldn’t have worked, simply reinforcing a mood that something had to give, and soon, and that that something would be the exchange rate. It wasn’t as if runs on advanced country fixed exchange rates were that uncommon: in 1992 for example, both the UK and Sweden tried to face down runs, allowing interest rates to adjust. In Sweden short-term interest rates got briefly to 500 per cent. But both countries devalued (if you are pretty sure a 20 per cent depreciation is coming within weeks even an interest rate of 10 per cent per month won’t stop you selling). And that was, more or less, the story. It would have been cheaper if Muldoon had accepted official advice and devalued in the middle of the election campaign but……you can understand why any politician would have resisted what would have looked like a mid-campaign concession of failure.

It was an expensive mess (the reserves were eventually – very quickly – bought back at a much higher price) but it was a liquidity issue, in the context of a strongly held official view that the rate needed to be lower, not a solvency one. The country was simply not on “the brink of bankruptcy”. The devaluation itself didn’t force any of the rest of what followed – as I noted, the reserves flowed back pretty quickly once the RB was no longer compelled to defend a rather arbitrary market price that people had lost confidence in. The IMF and external creditors forced nothing either. It was all just New Zealand policymakers’ own doing. And it wasn’t even all very consistent: in fact, the devaluation was followed – in a rather panicky move by Douglas – by the reimposition of a price freeze for several more months. But the atmosphere of crisis, exacerbated by the political shenanigans in the day or two after the election (NZ not having immediate transitions like the UK) made for a great foundation myth. (And curiously there was another run on the currency seven months later, in the days leading up to floating the exchange rate. The market consensus was that a floating exchange rate would fall, perhaps a lot. They were wrong. In fact, if one looks at a graph of the real exchange rate over decades, one could argue that the official view in mid 1984 (very strongly held, and repeated internally in the months following the devaluation) was also – with hindsight – wrong.)

I’ve marked the devaluation low. It was hardly ever revisited once the exchange rate was floated. But the beliefs in 1984 were widely held, in official and private circles here, as well as abroad (eg IMF). Devaluation itself was pretty inevitable against that backdrop.

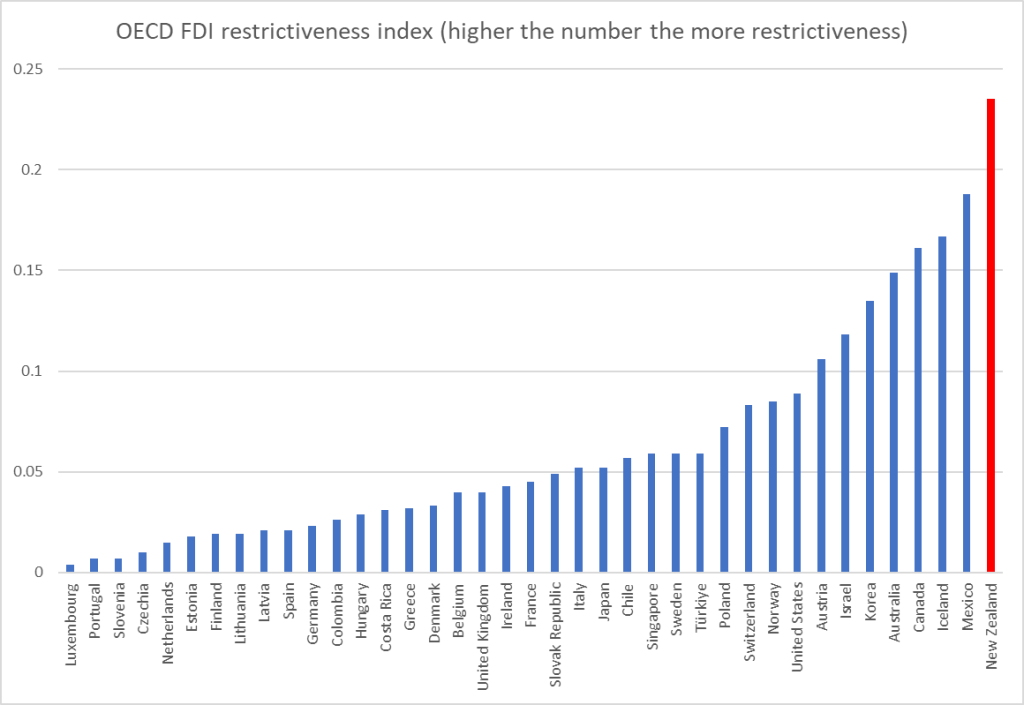

Six months ago today I wrote a post looking back at the economic outcomes that followed the far-reaching reform programme put in place over the following years. Since some of my right wing friends looked askance at the post, suggesting I was offering aid and comfort to the left, I should add that (a) I don’t hunt in a pack, and b) at the time I supported most of what was done, and c) still think a lot of it was the right thing to have done (and that much would have happened anyway, if in a more gradual and less rigorous fashion – the counterfactual was never one of no change). But it is also impossible to just look past the failure of New Zealand to reconverge with the OECD productivity leaders over the subsequent decades (we’ve dropped further behind almost all of them), or to ignore the utter disaster that has been New Zealand house prices, land use law etc. Again, we cannot know the counterfactual with any certainty. And we also cannot overlook very real gains (eg substantial trade liberalisation and much lower cost of imports etc). But it simply hasn’t been an unalloyed success story. If it were otherwise, New Zealand today would be a quite different – and better – place.

And if perhaps there are some signs that the political system is finally taking seriously the house price disaster – I’m reluctant to go further than that just yet – there is no sign at all that either side of politics much cares about the productivity failure.