I’ve written a few posts in the last few months about the strange approach that the Reserve Bank has been taking to thinking and talking about the impact of fiscal policy on demand since May’s Budget. Background to the material in this post is here (second half, from July), here (mid-section, commenting on the August MPS), and here (September, in the wake of PREFU.

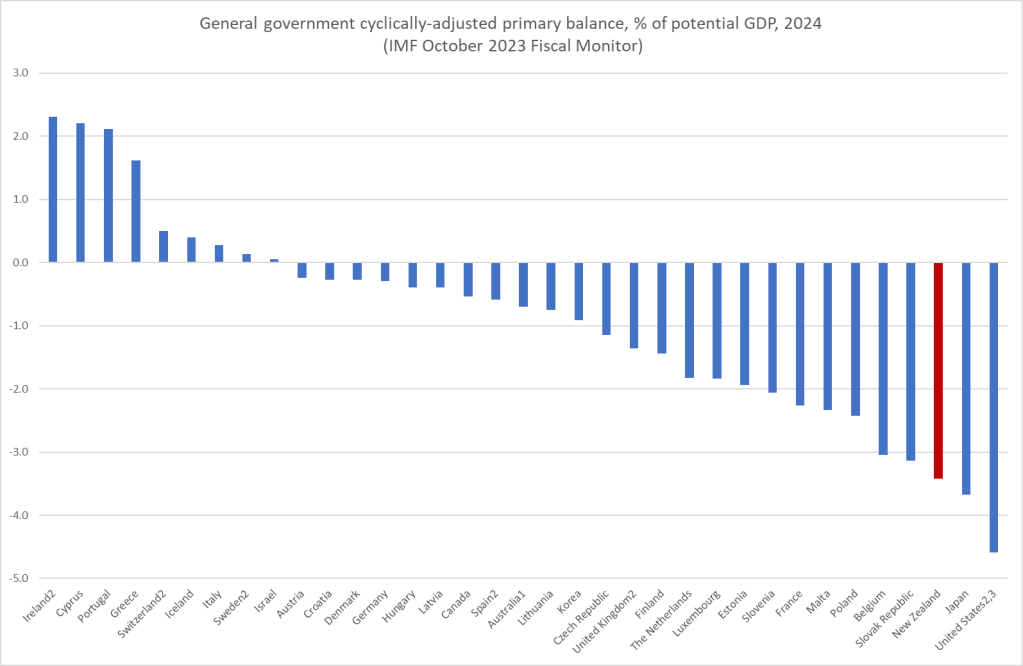

Up to and including the February MPS the Reserve Bank’s approach to fiscal issues was pretty much entirely conventional. What mattered mostly for them – and for the outlook for pressure on demand and inflation – was not the level of spending or the level of revenue or the makeup of either spending or revenue, but discretionary changes in the overall fiscal balance. Adjust the headline numbers for purely cyclical effects (eg tax revenue falls in economic downturns) and from the change in the resulting cyclically-adjusted surplus/deficit from one year to the next you get a “fiscal impulse”. That is/was an estimate of the pressure discretionary fiscal choices were putting on demand and inflation. For a long time, The Treasury routinely reported fiscal impulse estimates – and estimates they always are – along these lines, and had developed the indicator specifically for Reserve Bank purposes twenty years ago.

If the cyclically-adjusted deficit (surplus) is much the same from year to year the fiscal impulse will be roughly zero. A central bank typically isn’t interested that much in whether the budget is in surplus or deficit, simply in those discretionary changes. Back in the day, for example, we upset Michael Cullen late in his term when he was still running surpluses, but shrinking ones, when we pointed out that the resulting fiscal impulse (from discretionarily reducing the surplus) was putting additional pressure on demand and inflation, at a time when inflation was at or above the top of the target range. Whether or not what he was doing made sense as fiscal policy, it nonetheless had implications for the extent of monetary policy pressure required, and it was natural for us to point this out (as with any other major source of demand pressure).

Among mainstream economists none of this is or was contentious. International agencies, for example, routinely produce estimates of cyclically-adjusted fiscal balances, partly to help readers see the direction of discretionary fiscal policy choices. Plenty of past Reserve Bank documents will have enunciated this sort of approach.

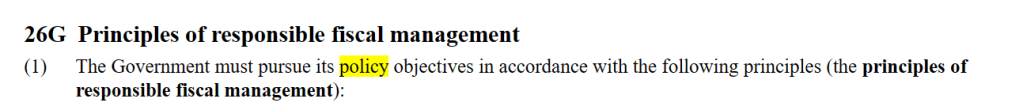

It was also this sort of thinking that led to an amendment to the Public Finance Act in 2013

(NB: The Treasury has made analysis of this sort harder in recent years, as in 2021 they changed the way they calculate and report the fiscal impulse, in ways that make little sense and reduce (but don’t eliminate) the usefulness of the measure as they report it. These changes further undermined the usefulness of New Zealand official fiscal indicators – already generally not internationally comparable – but do not change the fundamental economics, which is the focus in this post.)

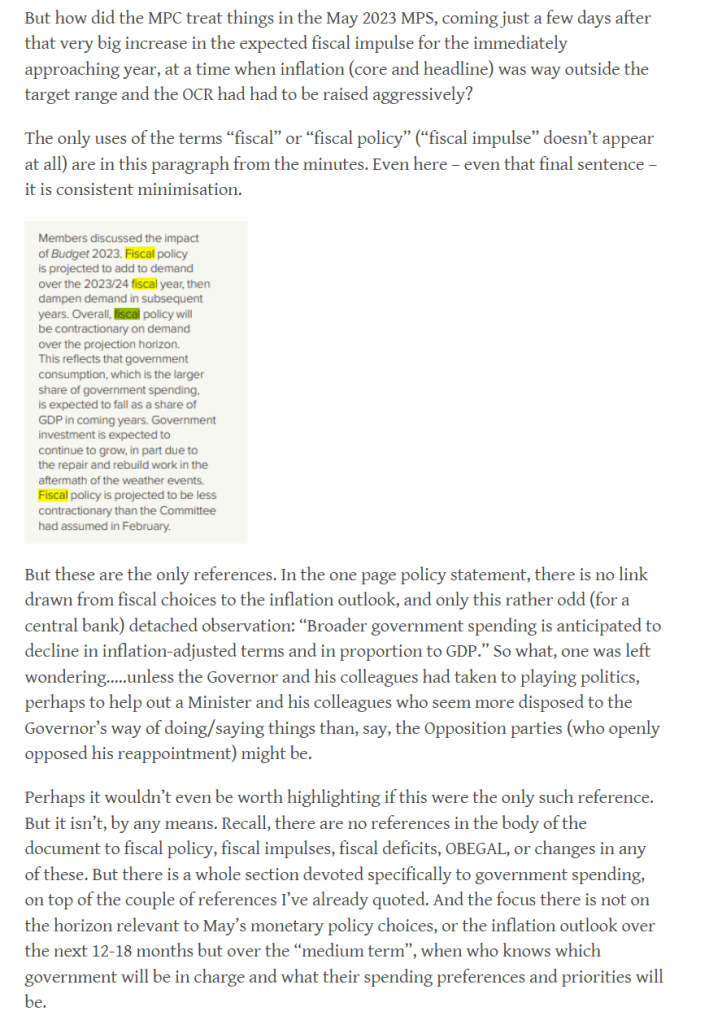

But suddenly, in the May Monetary Policy Statement – a document released just a few days after the government’s election-year Budget – there was a really major change in the approach the Bank and the MPC were taking to fiscal policy.

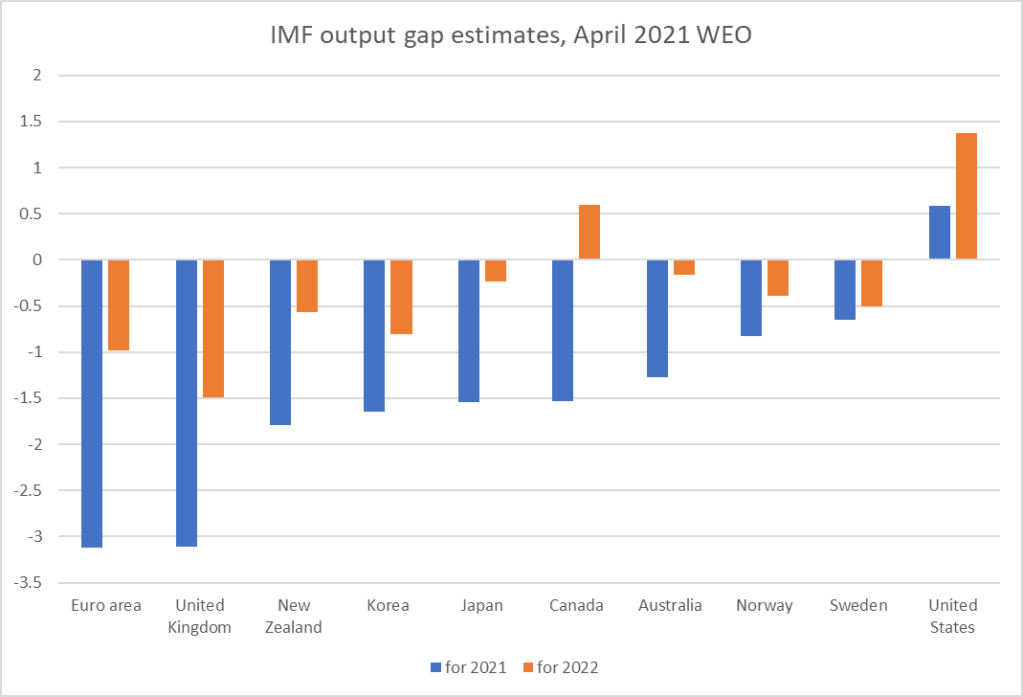

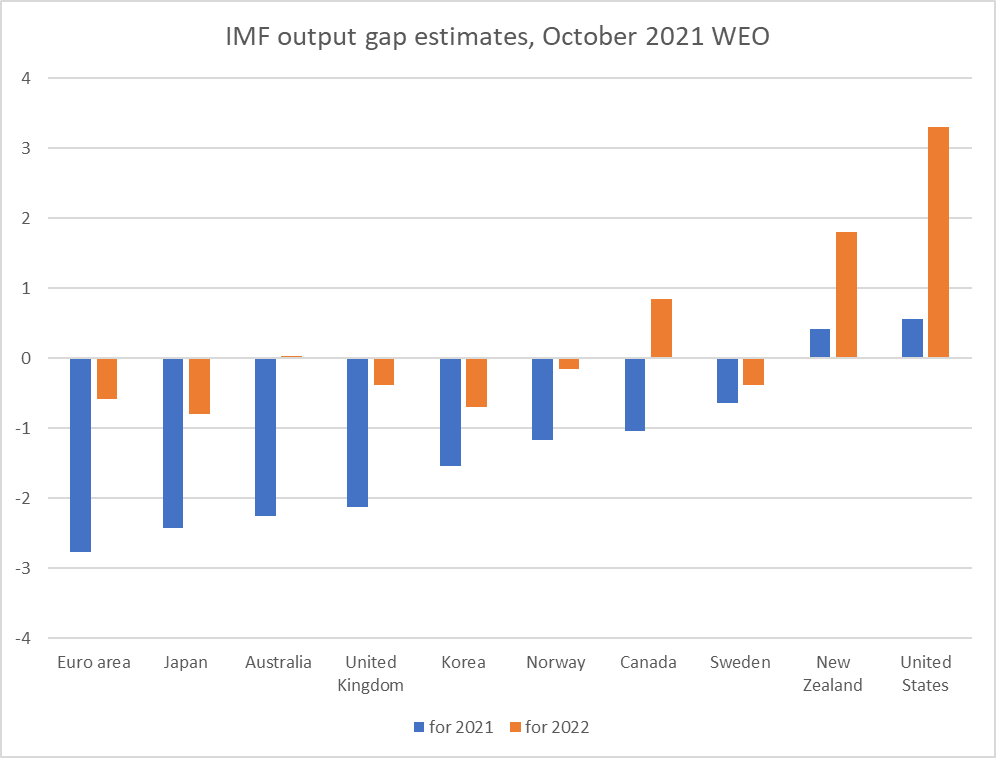

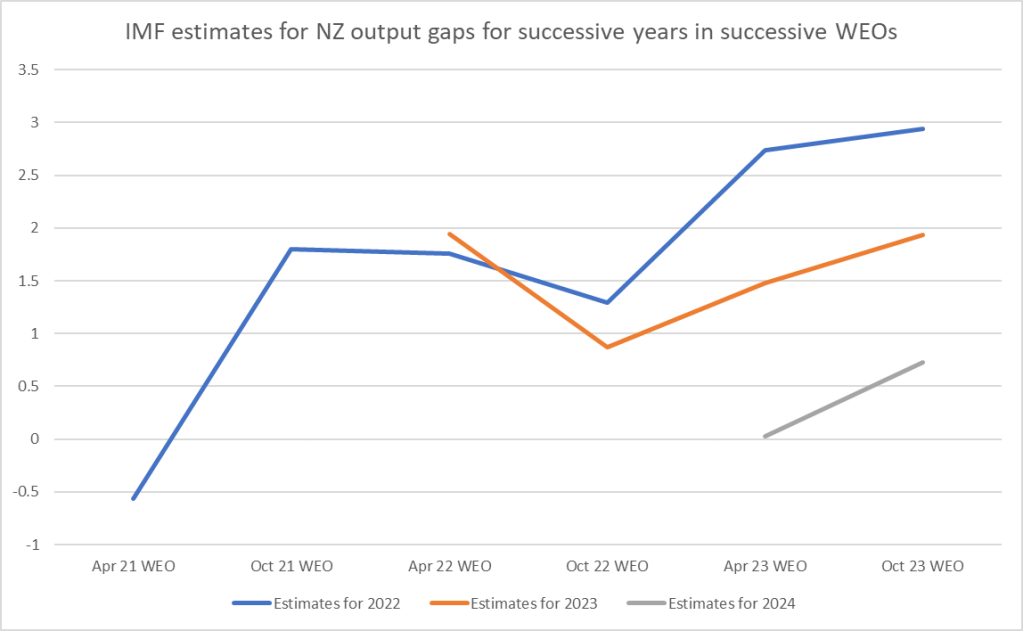

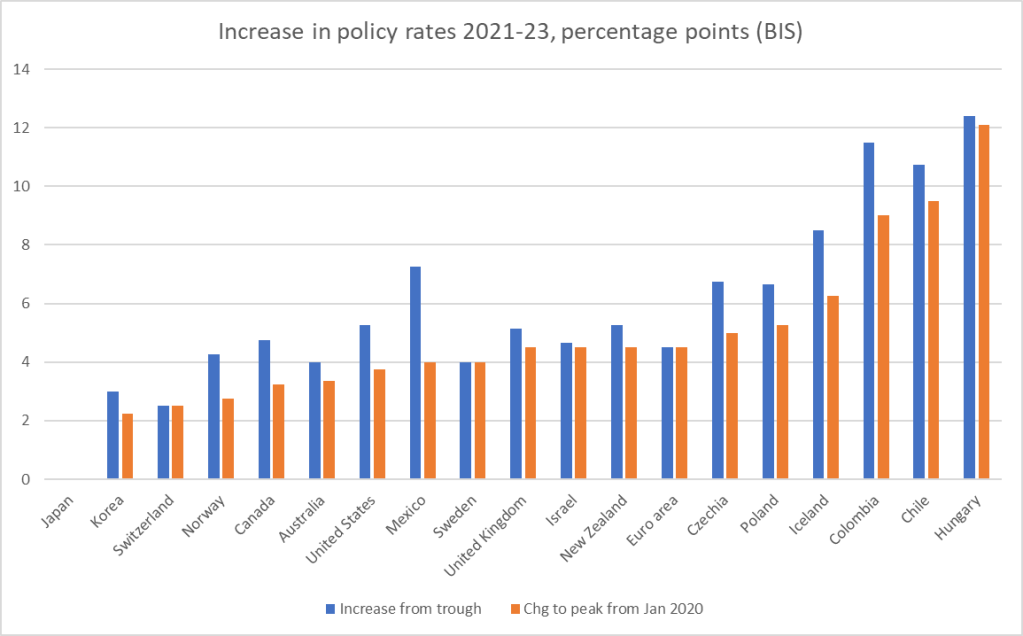

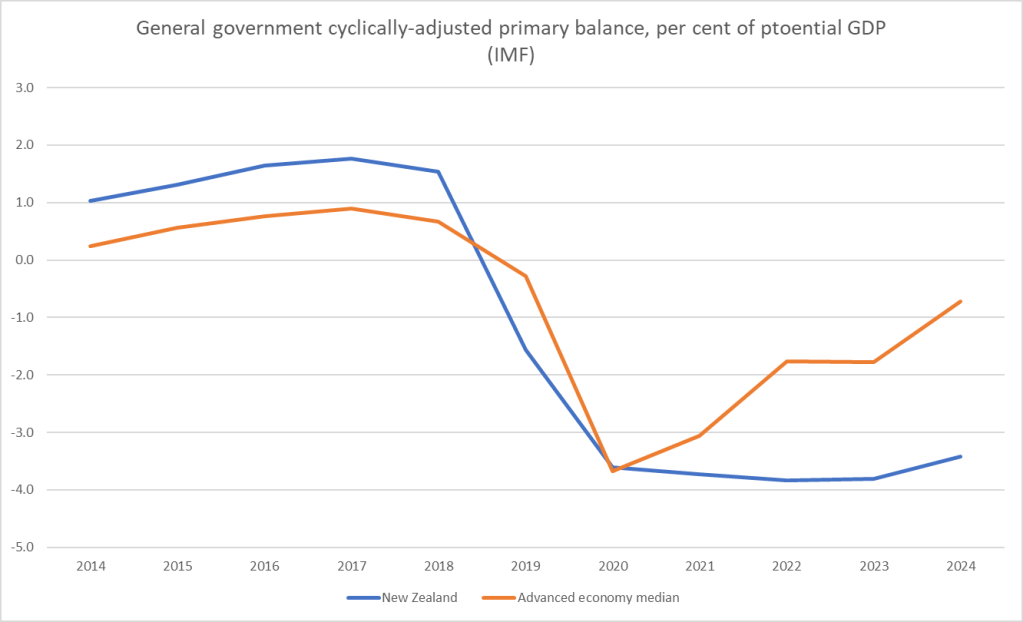

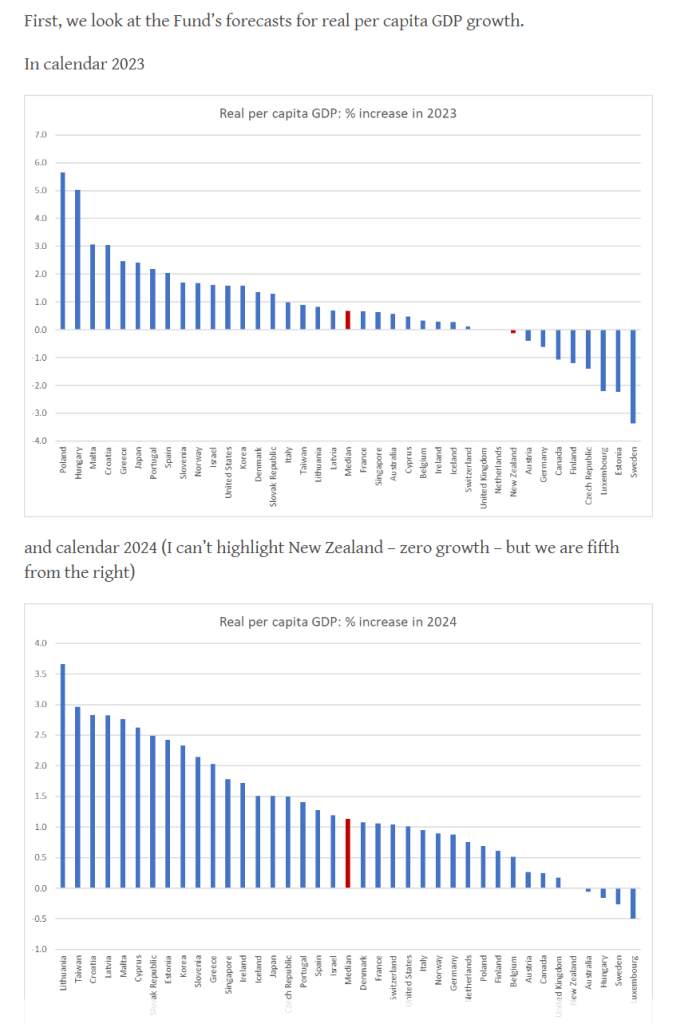

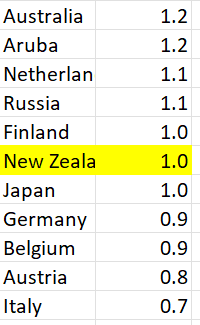

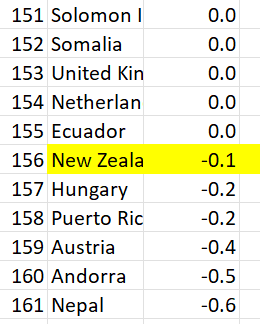

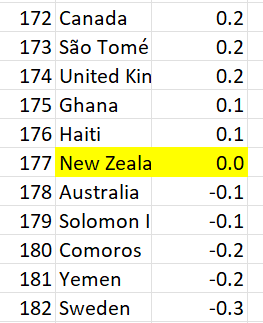

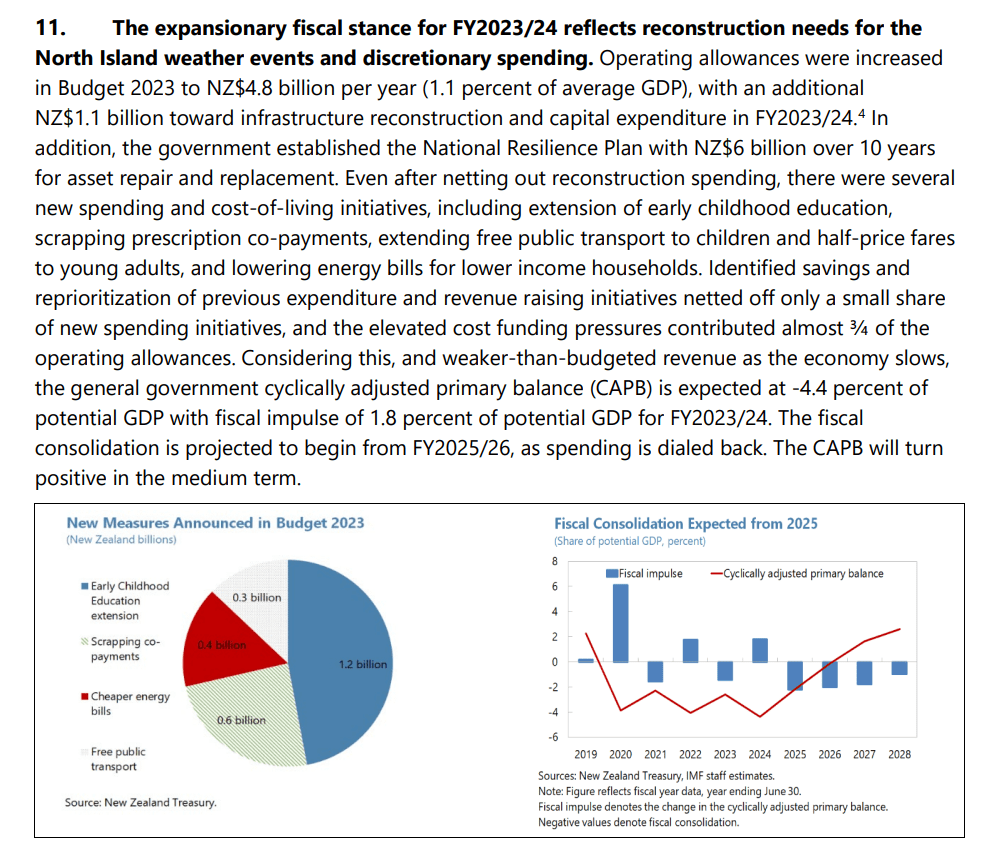

No one much doubts that the Budget was expansionary. Here, for example, was the IMF’s take in their Article IV review of New Zealand, published in August but finalised just 6-8 weeks after the Budget

There also wasn’t much doubt that the Budget (and thus demand pressures over the following 12-18 months – typically the focus of monetary policy interest) was more expansionary than had been flagged in the HYEFU at the end of last year. As I’d noted in the first post linked to above

For the key year – the one for which this Budget directly related – the estimated fiscal impulse had shifted from something moderately negative [in HYEFU] to something reasonably materially positive [in the Budget]. The difference is exactly 2.5 percentage points of GDP. That is a big shift in an important influence on the inflation outlook – which in turn should influence the monetary policy outlook – concentrated right in the policy window.

But how did the Reserve Bank treat the issue?

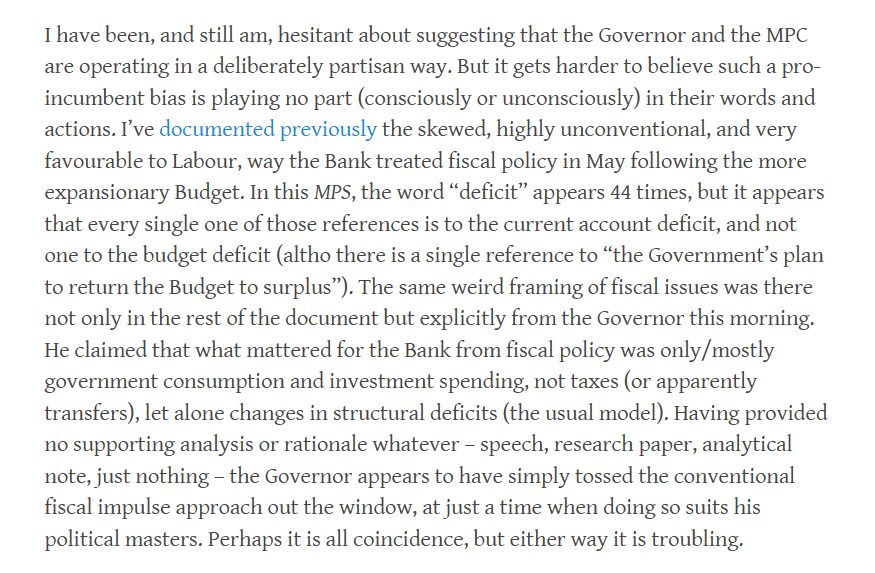

They were at it again in the August MPS, and in the next day’s appearance at FEC.

These sorts of lines – including one of the Governor’s favourites that fiscal policy was being “more friend than foe” – helped provide cover for the Minister of Finance, who was fond of suggesting to reporters that after all the Reserve Bank wasn’t raising any issues.

Some mix mystified and frustrated, I lodged an OIA request with the Bank seeking

If they really did have a thoughtful and well-researched new approach to thinking about fiscal policy and the impact on demand pressures, surely they’d be keen to get it out there. It didn’t seem likely there was anything – there were no footnoted references to forthcoming research papers etc – but….you never know.

But we do now. The Bank responded last month (I was away, and then distracted by election things so only came back to it last week). Their full response is here

RBNZ Sept 23 response to OIA re fiscal policy impact on demand and inflation

They withheld in full the relevant sections of the forecast papers that go to the MPC prior to each OCR review. This is a point of principle with the Bank whereby they assert that to release any forecast papers from recent history would “prejudice the substantial economic interests of New Zealand” (I did once get them to release to me 10 year old papers, from my side as point of principle too). It is a preposterous claim – and needs to be fought again with the Ombudsman (or perhaps a Minister of Finance seriously committed to an open and accountable central bank) – in respect of documents that are many months old, but for now it is what it is.

That said, it would be very surprising if there was anything at all enlightening on the Governor’s change of tack in those withheld papers. The Bank’s economic forecasters rarely did fiscal analysis very well and those sections of the forecast papers were often fairly perfunctory (recall that the Bank takes fiscal policy as conveyed to them by the Treasury, just adjusting the bottom line deficit/surplus numbers for differences in macroeconomic forecasts (eg affecting expected revenue for any given set of tax rates)). More importantly, in the documents released there is nothing else from prior to this change of official approach in May – no internal discussion papers, no draft research papers, no market commentaries circulated approvingly, no overseas academic pieces, just nothing.

In fact, the first document dates from 31 July this year, a 14 page note from analysts from a couple of teams in the Economics Department with the heading “Fiscal policy – seeking a common understanding”. Had there been a serious analytically-grounded push for a new approach, you might have expected such a paper to have been prepared and presented to internal groups and to the MPC well before such a change featured in the MPS. But that change was in May…..and the document dates from the end of July (may have been prepared with the then-forthcoming August MPS in mind). It has a distinct back-filling feel to it.

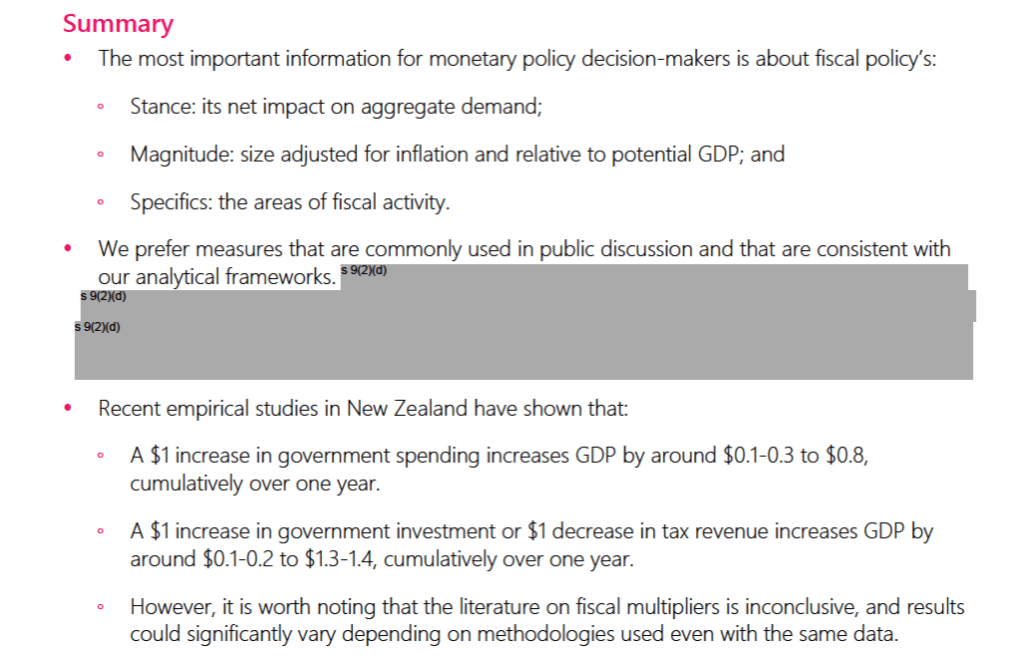

Here is the paper’s summary

You notice that again they are invoking alleged potential jeopardy to New Zealand “substantial economic interests” to tell us which fiscal indicators these two analysts favour – rather weirdly given that the Governor has already told us (in MPSs) and told Parliament’s FEC which ones he thinks matter most.

But that withholding quibble aside, there isn’t anything really to argue about in that summary. I’m not entirely convinced that a fiscal multipliers approach is the best way of tackling the issue, but having done so they report nothing – not a thing – suggesting that what matters for monetary policy is primarily government consumption and investment spending (as distinct from transfers, taxes, or overall fiscal balances). It is an entirely orthodox position, but quite at odds with the line the Governor and the MPSs had been spinning.

(The paper does have a short box noting in the Bank’s economic model – NZSIM – government consumption and investment are identified separately, while the model itself does not have explicit components for tax rates or transfers but – sensibly enough – this gets no further comment in the paper, and does not mean that changes in tax or transfer policy make no difference to the projections the MPC is considering).

There isn’t very much in the paper on the interaction with monetary policy, but there is this

which is all fine and shouldn’t be at all contentious, but none of its suggest that changes in fiscal deficits don’t matter for the extent of monetary policy pressure and that – as the Governor took to claiming in the wake of the expansionary Budget – that all that mattered was government consumption and investment.

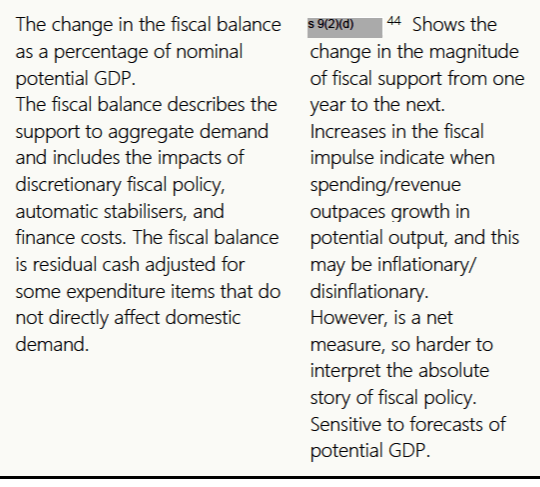

At the back of the paper there is a five page Appendix on all the Treasury measures of fiscal policy. Each appears to have been scored for “usefulness for monetary policy purposes” and while the comments have been released they appear to have withheld – jeopardising those substantial economic interests again apparently – scores or rankings of each item.

They do have items for Government Consumption and Government Investment. Under “usefulness for monetary policy purposes” the comment – on both – is simply “Government consumption [investment] provides information about the type and size of government activity”. Quite so, but…..not really about monetary policy.

But then we come to the item “Total Fiscal Impulse”. Here is what they say

These analysts from the Bank’s Economics Department are entirely orthodox. I would qualify their comments slightly because – as alluded to above – this new “Total Fiscal Impulse” measure is clearly inferior for purpose than the previous Fiscal Impulse, but they are clearly on the right track. They recognise that changes in fiscal balances can affect the outlook for demand and inflation (and hence monetary policy pressure). They go on to briefly note that the impulse was estimated to be strongly positive in the 2023/24 fiscal year (the primary focus for monetary policy at the time).

It isn’t a startlingly insightful paper, but that is fine. It is largely rehearsing long-established conventional perspectives, and if it was at odds with anyone……well, it was only with the Governor and the MPC. And I guess one can’t really expect junior analysts to take on the powers that be. But it is still just a little surprising perhaps that this 31 July paper contains no reference – not one – to the strange new Orr model that had suddenly overtaken the MPS. One might, for example, have hoped that the Chief Economist might have provided a lead, and even perhaps affixed his name to the paper…..but then he is an Orr-appointee and must have signed up to the weird MPS approach too.

There is one more document in what the Bank has released to me. It is undated, has no identified author, and is headed “Fiscal policy in the August 2023 MPS”, suggesting that there is a reasonable chance it was written specifically for the purposes of responding to my OIA.

There are two parts to this 1.5 page document. The first page lists four statements on matters fiscal from the August MPS and outlines “supporting evidence”. Of those, three are simply irrelevant: there has never been any dispute about the fact that in the 2023 Budget real government consumption and investment was expected to fall as a share of GDP over the next few years (although note that for setting monetary policy in mid 2023, what might or might not happen to some components of the budget in 2026 is simply irrelevant – monetary policy lags are shorter than that).

The fourth is “interesting”

You might have supposed that this statement had appeared in the August MPS. It doesn’t. “Fiscal policy” hardly appears at all (and nothing about what it will be doing over the period monetary policy is focused on) and “discretionary fiscal policy” doesn’t appear at all.

But beyond that it is still just spin. What happens by 2027 is (again) irrelevant to today’s monetary policy, and even if the cyclically-adjusted deficit is still forecast to narrow in the shorter-term the extent of that narrowing by Budget 2023 was materially less than what had been envisaged – and included in the RB forecasts – at HYEFU 2022. Fiscal policy is putting more pressure on inflation and demand than had been envisaged at the end of last year, exacerbating pressures on monetary policy. That was – and apparently is – the point the Governor still prefers to avoid acknowledging…..something Robertson was probably grateful for.

The second half of this little note is headed “Why haven’t we referred to other measures of fiscal policy?”

Of the four bullets, again there is no real argument with three of them

To which one can mostly only say “indeed”, but then no one suggested the central bank should look at either of the allowances – which in any case are only on the spending side of the balance. As for the operating balance, I’m not going to disagree, but……mentioning it would be typically less bad than the highly political mention of only one bit of the overall fiscal balance (direct government consumption and investment).

What of the fourth?

That is just weird. Take that penultimate sentence: it is a change measure that you want when it is monetary policy and inflation you are responsible for. The change is what changes the outlook for demand and inflation. But then there is the rank dishonesty of the final sentence. They prefer to “supplement the total fiscal impulse” do they? But there was no reference to it – or to words/idea cognate to it – in either the May or August MPS. And the claim that they can somehow sensibly supplement as fiscal balance based measure – which already includes taxes, transfers, and real spending – with “real government spending” is, it seems, simply plucked from thin air. It doesn’t describe what they’ve actually done these last two MPSs, it isn’t an approach even mentioned in the Economics Department’s July note (see above), and as far as I can see it has no theoretical or practical basis whatever.

It is just making stuff up.

We’ve had several previous attempts by Orr to actively mislead (Parliament or public) or make claims that prove to have no factual analytical foundations. There was the claim to FEC that the Bank had done its own research on climate change threats to financial stability, claims trying to minimise the extent of turnover of senior managers, claims regarding the impact of this year’s storms on inflation, claims that inflation was mostly other people’s fault (notably Vladimir Putin). Each of these has been unpicked in one way or another – the first via the OIA, the second via a leak, the third via one of his own staff piping up to correct things in FEC, the fourth simply be patiently setting down the numbers and timing. There have also been entirely tendentious claims around the LSAP, including his attempt – repeated in the recent Annual Report – to assert that the LSAP made money for taxpayers, despite the simplest review of the exercise he used in support of this claim showing that it simply didn’t provide any serious support for his view.

Every single one of those was bad, and should have been considered unacceptable, by both the Minister of Finance and the Bank’s Board. A decent and honourable Governor would simply never have done them. But bad as they were, those were self-serving misrepresentations.

What has gone on around fiscal policy this election year seems materially worse. We make central banks operationally independent in the hope that they will do their job without fear or favour, and without even hint of partisan interest. But faced with a Budget that complicated the task of getting inflation down, that was materially more expansionary than had been envisaged just a few months previously, Orr (and his MPC colleagues, reluctantly or otherwise) chose to completely upend the traditional approach to thinking about fiscal impacts on demand and inflation pressures, and tell a story – and a story it was – that tried to gloss over what the Minister of Finance had done, ignoring what mattered in favour of what was at best peripheral. Whether that was for overt partisan purposes is probably unknowable from any documents likely to exist, but it is hard to think of any other good explanation for what was done, espeically when – as this release shows – it was all based on no supporting analysis or research whatever.

The Official Information Act plays a vital role in helping expose events like this. It was never likely there was anything of substance behind Orr’s fiscal spin. But now we know.

(As to the attitudes of other MPC members, who clearly all went along since not a hint of a conventional perspective is in the minutes of the meetings around either MPS, there is a tantalising bit that was also withheld

Only one of the three relevant MPC meetings during this period, but the most recent. Was there some gentle unease from perhaps one member? We may never know, but at least this withholding appears to confirm that there are fuller minutes of MPC meeting, not just the bland summary published with each OCR announcement.)

PS. It is perhaps no surprise that the Reserve Bank has chosen not to put this OIA release out on their OIA releases page, even though that page was updated just a couple of weeks ago. It does not put the Bank in a good light.