I suppose all Prime Ministers these days feel the need to spin.

Ours was at it again yesterday. She was talking over breakfast – a vegetarian one the Herald account tells us – to the Trans-Tasman Business Circle. Her topic?

The topic I have been given for today – ‘The Future of Work and how the government is preparing for the economic challenges of the future’

It is pretty much downhill from there.

Countries the world over are currently grappling with digital transformation, and transitioning their economies, and New Zealand is no different in that regard.

Even if you pardon that abuse of the language (“transitioning”), does anyone have any idea what this means. Individuals and firms are getting on with their lives, looking for opportunities, as it long has been and no doubt long will be. Are technologies different than they were fifteen years ago? Of course. But is our economy that different than it was fifteen ago? Sadly, probably less so than one would hope.

That isn’t the prime ministerial spin though

Where we are different, I believe, is in the way we are responding to those challenges, turning many of them into opportunities.

The country with weak productivity growth, drifting further behind the rest of the advanced world, and with declining shares of GDP accounted for by trade with the rest of the world.

As it happens, the annual national accounts were released later yesterday morning. I was playing around with the data and might use it for various posts in the next few days, but since the PM was talking about “digital transformation” I thought this chart was interesting.

Now not all of these, by any means, are about the narrow “digital transformation”, but if such a thing were happening on a large scale, in which new world-beating opportunities were being developed and seized, these indicators are among those where we might expect to see it. As it is, over the last few years things to have been more or less going sideways.

The PM went on to first offer some context

Firstly, the NZ economy is in good heart amid the global challenges and what many believe are new economic normals,

Well, okay, believe that if you want. But most respondents to surveys don’t share your positivity, and in general they are less likely to be motivated reasoners than a PM. And

Secondly, the Government and Reserve Bank are doing their bit to ensure that fitness endures and it’s important business continues to work with us too – after all, we mustn’t talk ourselves into a funk

We are right, you are wrong. Get with the message. Or at least that seemed to be what she was suggesting. Just a shame the data don’t tend to support her. I’m still not sure what the Reserve Bank has to do with “that fitness” (whatever it is) – presumably she hasn’t had it schooled into her that the OCR is typically cut (in an economy without big positive productivity shocks) because demand is weak and things aren’t going that well. Oh, and is she perhaps aware of those big new capital requirements the Governor is wanting to impose on banks, and hence on the availability of credit to the economy? If she is embracing those, that would be an interesting call – her Finance Minister has been very careful to disown all responsibility.

Anyway, she gets into her stride in a section headed “It’s the economy”.

All of you in this room will know that this Government’s approach to the economy is that it is not an end it itself but, rather, a means to an end.

Which might be news if, just perhaps, she could point us to any government in history, or even just New Zealand history, for whom that was ever not so.

That of course means building strong economic foundations. And on that front we’re doing pretty damn well actually, especially amid global uncertainty.

The argument must be weak so lower the tone of the language. No one is going to dispute that successive New Zealand governments have successfully focused on budget balance and a modest level of debt. What about her other claims?

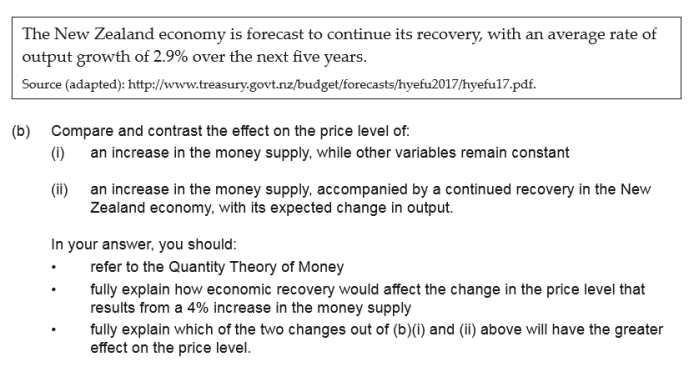

So far our policies have delivered growth of 0.5 percent in the June quarter and average growth of 2.4 percent in the year ending June. That shows that the New Zealand economy continues to outperform those of Australia, Canada, the Euro area, the UK, and the OECD average – basically those we compare ourselves to.

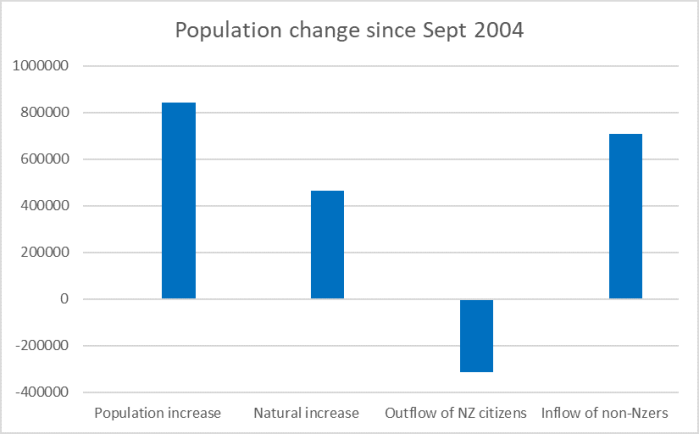

That tired old line so beloved of whoever is in office, right or left, and their champions. Never mind that we have substantially faster population growth than all of those countries except Australia and that any reasonable and honest use of GDP statistics in a a discussion about success, wellbeing or whatever, starts from a discussion of GDP per capita. On that score, there is nothing impressive about even our recent record, let alone the longer-run picture.

Also, recent data shows New Zealand’s manufacturing and services sectors are both expanding.

Well, yes that is probably so, but…..when your population is growing by 1.5+ per cent per annum if those sectors (ie the bulk of the economy) were actually contracting it would be really quite alarming.

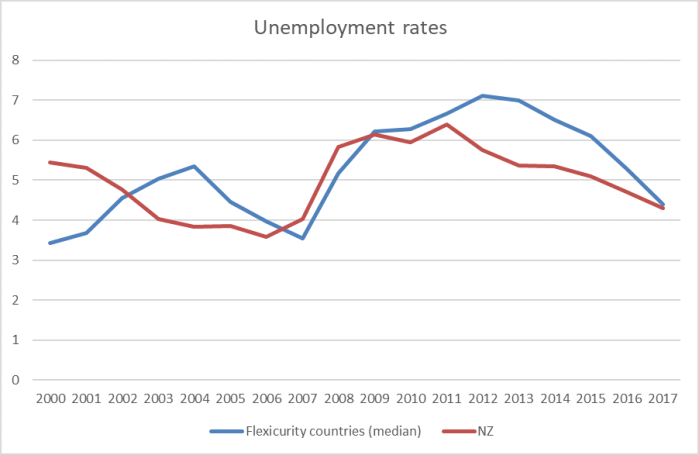

We have record low unemployment and annual wage growth is at its highest level since the 2008 financial crisis. Average wages have increased by 4.2% in the last year alone.

Yes, relatively low average unemployment – consistent with the typical person being unemployed for “only” two years in a working life – is one of the successes of the New Zealand policy framework. But the current rate is nowhere near a “record low” – not even during the 30+ years of the HLFS (that was just prior to the last recession), let alone the post-war decades prior to the quarterly survey getting going.

New Zealand continues to be a good place to do business, topping the World Bank’s 2019 Ease of Doing Business index. Our globally competitive economy is underpinned with stable political and regulatory systems, an innovative well-educated population and our proximity to 60 percent of the world’s population. We are a safe place to invest.

Such a great place to do business in fact that (a) business investment remains persistently weak, especially given the surge in the population, (b) our economy is becoming more inward-focused (trade shares have been falling) and (c) another tired old line – we are close to 60 per cent of the world’s population – that bears just no relation to reality whatever. Yes, we are closer to the centre of gravity of world economic activity than we were 100 years ago – when we traded mostly with the then-dominant power the UK – but these days the UK is still closer to India and as close to China as we are. In both cases, far away. Oh, and we are also a long way from those leading productivity economies in Europe and North America.

And last on this list

And you’ll note that when the Reserve Bank announced its decision to hold the Official Cash Rate at 1 percent last week, its analysis confirmed the economy is in good shape, amid global economic headwinds. The Bank pointed out that employment is pretty much at its maximum sustainable level, residential investment is increasing and that economic growth is expected to rise next year, due to the Government’s investments. While the RBNZ noted that global headwinds have impacted business confidence in New Zealand, it also said that our investments are forecast to support and grow the economy next year.

When the Prime Minister says “investments” here she really just means more government spending, most of it consumption or transfers. Probably she didn’t read the Reserve Bank’s statement, but she will have had a personal briefing from the Governor. He too is inclined to spin, but his document had a rather lot on the downside risks – in fact they explicitly noted, and formed policy on the basis of, the balance of risks being to the downside. And while the Bank had rather upbeat growth forecasts, few private economists shared their optimism.

I am not wanting to suggest things are disastrously bad, at least in a short-term cyclical sense in New Zealand, but at very very least the PM is gilding the lily. Perhaps you might think that is her job, and on a bad day I could share the cynicism, but we really should expect something better from people who hold office as leaders.

But her own summary is this

Ultimately, we have a positive story to tell, including to investors, and one of my consistent messages is that we are a stable, reliable investment option, with plenty of success stories. Now, domestically, we all need to act like it.

I’m right, you are wrong, get with the message. Or so it seems. And, yes, we do have a fair measure of political stability – no Brexits, no civil wars etc, no impeachment hearings (just the ongoing stench of the political donations scandals) – but that doesn’t markus out from most advanced countries, those that have been performing pretty strongly – actually securing the productivity gains on which so much else rests – and those, like New Zealand, that haven’t.

The next section is headed “Govt doing its bit”. Here there is a lot about capital investment

It won’t surprise you to hear me say – infrastructure, infrastructure and infrastructure. There’s no question that we have a range of deep policy issues to address as a nation, but unless we get the basics right of providing decent housing, transport and health and education services, we’ll only compound those more complex issues. That’s why the Government’s Economic Plan, which you will have heard many Ministers talk about, is designed to build an economy that protects and improves the living standards and wellbeing of all New Zealanders through ensuring we get those most basic fundamentals right.

That’s why we are investing record amounts in hospital and school building programmes – including the fact that in our first two Budgets we’ve invested $2.45b into upgrading and building new hospital and health facilities- that’s twice as much as the previous government managed in nine Budgets – alongside large investments in transport safety, regional roads, and public transport, and we’ve done that while maintaining a responsible budget surplus.

“The Government’s Economic Plan“: that’s a good line. I hope it got a laugh. But perhaps the audience were more polite than that. Infrastructure? Well, shame about the roads that aren’t getting built, even as the population grows rapidly. And here is another chart from the annual national accounts, showing general government investment spending as a share of GDP.

Nothing startling about spending in the first full year of this government. But perhaps it will be different in years to come.

And then the empty boasts about housing

Not to mention our comprehensive plan to fix the housing crisis which includes delivery of: more state houses than any Government since the 1970s, banning offshore speculators, expanding Housing First to end homelessness, a $400 million package for a progressive home ownership scheme, and making saving for a house deposit easier by lowering the deposit required for a Government-backed mortgage or first home grant from 10 per cent to five per cent. These are real, tangible, things that will help New Zealanders and their families.

“Comprehensive plan” and yet not a mention of the only thing that would make a durable, substantial and sustainable difference, lowering prics of houses and urban land, land use reform. Allowing people to borrow 95 per cent LVR loans – even as her Reserve Bank keeps on LVR restrictions on private credit – is at best papering over the cracks of the failures, chosen, of successive governments, including her own. But give her credit for consistency: Labour leaders (whether Little or Ardern) have never been willing to champion serious land use liberalisation.

A little further one and we get this recapitulation

Ultimately, this [Infrastructure Commission report] should all be sending two really strong signals. That we are planning for the future and that now is the time to invest. New Zealand is doing well and there are enormous opportunities if we act now. The best thing for the NZ economy at the moment is optimism, planning and investment action. We’re doing some pretty heavy lifting to shore that up in terms of spending and infrastructure investment, the RBNZ is doing its bit with record low interest rates – the private sector needs to ensure it’s on board too.

But, our economy (a) isn’t doing that well (see above) (b) and firms – people with shareholders’ money on the line clearly aren’t seeing “enormous opportunities” to invest, either now or (in fact) for decaders past. If it were otherwise now then, all else equal, interest rates just wouldn’t be this low – as a macro 101 reminder to the PM, interest rates are low because demand for resources at any higher interest rates would be even weaker.

But the PM enjoins us to “only believe”, to join some sort of cheerleading squad building castles in the air.

In fact, one of my staff members asked an economist earlier this week to sum up the economy in one sentence and was told – “it’s ready for lift-off”. I could not agree more.

Perhaps there is such an economist. Perhaps he/she doesn’t even work in DPMC/PMO. Perhaps there even will be a bit of a recovery next year. But just nothing suggests this economy is “ready for lift-off”. The basic imbalances and severe structural problems haven’t been addressed, haven’t changed.

She goes on. There is the claim

we have laid out a clear agenda. Yes, it includes change, but by now you’ll all know what that agenda entails and how we’ll deliver it.

Somehow, I suspect the farmers angsting about the current water proposals don’t see it that way. And the government might have passed a Zero Carbon Bill, but (whatever its merits) it involves almost no substantive certainty about anything affecting business. Do we know what is happening about Fair Pay Agreements? And so on.

The speech goes on into a variety of other areas. The last I wanted to comment on was this – something to look forward to next week

Today I am also able to provide you with some insight into an upcoming announcement for the Forum. On November 25 the Forum will publish its Strategic Assessment of Future of Work Priorities. This presents four initiatives as priorities:

- The first is Industry Transformation Plans which will ensure we add value to key sectors of our economy and leverage new opportunities. These plans – for the food and beverage, digital technology, forestry and wood processing, and construction and agritech sectors will describe an agreed vision for the future of each sector, and set out actions required to realise this vision.

(So actually, some of the “clear agenda” isn’t laid out yet, but will be next week?)

Presumably the Prime Minister takes this stuff seriously, but really who supposes that a bunch of central planners, bureaucrats and their corporate equivalents, are really likely to come up with anything useful in these “industry transformation plans”. Haven’t we had numerous such plans before, stretching back many decades, and precisely what useful has come of them? Market economies just don’t succeed with “agreed visions” across government and the upper tiers of existing industry players, but by competition, trial and error, creative destruction, unexpected discoveries…..all supported perhaps by governments willing to do what it takes to put a supportive overall policy environment in place. Our goverment, much like its predecessors, is all too fond of the status quo, and unwilling to – probably uninterested in – getting to the bottom of why that continues to produce such mediocre economic results.

As a hint, the real exchange rate – a key relative price that never seems to make it to the PM’s upbeat economic speeches – remains well out of line with what you might expect for a country with such a disappointing long-run trade and productivity record. It might be consistent with that performance, but simply isn’t consistent with delivering something much better, that “productive and sustainable” mantra ministers always keep reciting, while never doing anything much to bring about.

I guess Prime Ministers feel the need to spin, perhaps especially those who aren’t willing to do much substantial. But it is a shame there isn’t a lot more honesty about the underwhelming state of the New Zealand economy and the reluctance of our policymakers and their advisers to do anything much about changing it. Sheer spin might get a good headline in the next day’s newspaper, but longer-term it just feeds the growing cynicism about politicians and the political process. It is cheap, has some short-term sugar-high effect, but is pretty deeply corrosive. Why take seriously anything they say?

Or perhaps the MPC is back to thinking that credit conditions really don’t matter at all? Surely, either way it would be reasonable to explain their perspective. Instead they seem to have simply ignored the issue (or tried to pretend the Governor’s whim wasn’t an issue – I heard Hawkesby on the radio this morning saying they had in fact taken account of credit conditions issues, in which case the OCR decision is still more mystifying, and the absence of any reference in the official documents looks even worse).

Or perhaps the MPC is back to thinking that credit conditions really don’t matter at all? Surely, either way it would be reasonable to explain their perspective. Instead they seem to have simply ignored the issue (or tried to pretend the Governor’s whim wasn’t an issue – I heard Hawkesby on the radio this morning saying they had in fact taken account of credit conditions issues, in which case the OCR decision is still more mystifying, and the absence of any reference in the official documents looks even worse).