Five and a half months into his Governorship, we’ve not had a single on-the-record speech from Adrian Orr about stuff that he is actually directly responsible for. There hasn’t been a single speech about monetary policy – still, by law, the Bank’s “primary function“. There hasn’t been one either about banking regulation and supervision, financial stability more generally, let alone about the regulation of insurers and non-bank deposit-takers. That is the stuff New Zealanders’ hard-earned taxes are paying him for, the job in which he is handed a great deal of discretionary policy power. It is almost as if – despite all the talk, all the cartoons – he has set himself the goal of being less open, less transparent, about stuff he should be accountable for than his ill-starred predecessor Graeme Wheeler.

Because even though Orr avoids talking about what he is responsible for, he talks a great deal – but rather loosely – about almost everything else (almost all from the liberal agenda) under the sun. There has been infrastructure, agriculture, climate change, bank conduct – which you might think was the Bank’s business, but isn’t (it is, by law, a prudential regulator, not a conduct one) – and so on. Off-the-record at a recent event he has reportedly threatened a Royal Commission on banking conduct. It is almost as if he thinks of himself as a politician. On the record, his only speech until recently was championing some big corporate buddies and their exercise in climate change virtue-signalling, assiduously keeping on side with the new government.

Perhaps there is a gap in the market on the left-wing side of politics, where effective and capable leadership seems to be sorely lacking (come to think of it, that is probably so on the right-wing (so-called) side of politics too). But if Orr is pursuing the bigger prizes he simply shouldn’t be doing it from the office of Reserve Bank Governor. It matters, or should do, that people across the political spectrum (and with no interest in politics at all) can be confident that the Governor is using his office solely for the statutory purposes, and not to advance and champion personal political agendas. I was no great fan of Graeme Wheeler’s, but I did believe that about him – for all his faults, he was a self-effacing public servant. Orr gives us no reason to have that confidence in him. That degrades the institution.

The fact that most of Orr’s publicly-championed political preferences probably chime quite well with those of the current left-wing government shouldn’t make it any more acceptable than if he were championing causes favoured by, say, ACT or the Conservative Party (although at least in that case we’d be sure he was acting independently, not shilling for his mates or his personal ideologies, or in pursuit perhaps of victories in the various turf battles around the structures and responsibilities of the Bank). It simply shouldn’t be happening. It is an abuse of office, and the Minister of Finance and the Bank’s (supine) Board should be calling him out and insisting on a change in behaviour.

Last Friday we had another (very long) on-the-record speech from the Governor. This one was under the heading “Geopolitics, New Zealand and the winds of change”. It was odd from the start. When the advisory came round telling us the speech – to a Workplace Savings conference – was forthcoming, I wondered if any incumbent central bank Governor had ever given a speech with “geopolitics” in the title. It didn’t seem very likely. Most largely try to stay moderately close to their knitting – the core responsibilities of their office. And then, on reading the speech, it was odd to find that (notwithstanding the title) there was no references to geopolitics at all – the word or the thing. That was a relief. But what happened I wonder? Did his senior advisers, the Minister of Finance, or MFAT prevail on him at the last minute to remove some material?

The Governor started his speech counter-punching

I know many people will be thinking, ‘what has the Reserve Bank Governor got to say about anything long-term? Doesn’t the Bank just sit and watch for outbreaks of inflation – shifting the official interest rate on a needs-be basis? Some will even comment publicly, ‘How dare the Governor speak outside of their 1 to 3 percent inflation mandate!’

I guess that was people like me. No one has suggested that the Governor talk only about monetary policy – although it would be a nice change if he did talk about it (say, preparing for the next recession) – and, after all, the Bank has extensive financial regulatory responsibilities. No one would think it amiss if the Governor gave us a thoughtful analysis of just what is going on in the New Zealand economy at present, and how that fits with inflation prospects or financial risks. But we’ve heard nothing like that. And the Governor isn’t the Minister of Finance, he isn’t head of a think-tank, he isn’t an academic: instead he is a public servant, supposed to be politically neutral, operating within a specific legislative mandate. If the Chief Justice or the Commissioner of Police were giving speeches like Orr’s it would be at least as inappropriate.

The Governor goes on

I hope to convince you we have a strong vested interest in, and influence on, the long-term economic wellbeing of New Zealand.

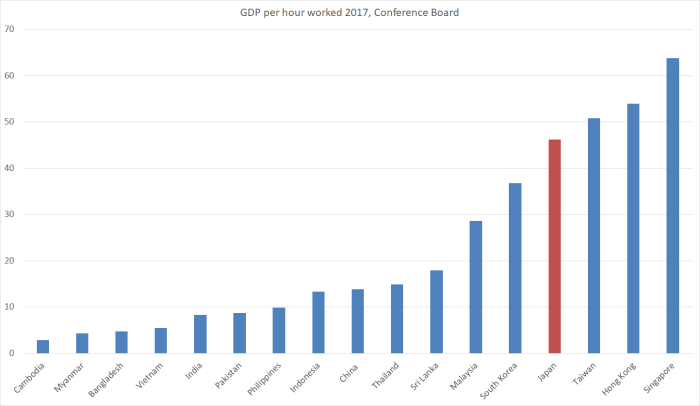

“We” here being the Reserve Bank. But this is just wrong-headed (and inconsistent with the lines run by all his modern predecessors). A country can have low and stable inflation and be poor or just underperforming (the latter the New Zealand story for decades), and it could have quite high inflation and still do rather well (see, for example, Turkey where labour productivity had almost caught up with that in New Zealand). Discretionary monetary policy is, almost of its nature, about shorter-term economic stabilisation – which matters a lot, but is just a quite different set of issues than those about longer-term prosperity. Much the same goes for banking (and related) regulation – to the extent it has a useful place, it is mostly about avoiding or limiting the short-term (but multi year) disruption that can accompany financial crises. But, as the US amply demonstrates, financial crises – nasty and disruptive, and even expensive, as they can be (and often having their roots in policy choices by regulators and their masters) – aren’t inconsistent with long-term prosperity. Oh, and relatively poor or underperforming economies can still have a high degree of financial stability – see, for example, New Zealand.

But Orr doesn’t make a contrary case, or demonstrate his proposition. He just asserts the connection between what he wants to say and the job he is paid to do. And then moves on to six pages of (single-spaced) text on

I summarise the key plague on economic society as ‘short-termism’. This is the overt focus on the next day, week, or reporting cycle. In contrast, by long-term, I mean anything that ranges from ‘outcomes’ over the next few years, through to an ‘idealised vision’ that could last inter-generationally.

Remarkably, he advances not a shred of evidence, or sustained analysis, in support of his proposition. Not that that is new, of course, A few months ago he told the Finance and Expenditure Committee that banks and their customers had too much of a short-term focus, and thus he – presumably blessed with an “appropriate” long-term perspective – needed to step in. But when I asked about any work the Bank had done to support such propositions, it turned out that there was none. It was just off the top of his head.

It probably sounds good – especially to senior bureaucrats not much given to introspection or historical reflection – to claim that there is too much short-term thinking in the world. If only, if only, (they probably think) people would defer to people like them, the world would be a much better place.

Someone pointed out to me yesterday that Orr’s speech was strongly reminiscent of (the great US economist) Thomas Sowell’s description of the “conceit of the anointed” in his 1995 book. I haven’t read the book, but as I dug some reviews and extracts, I was struck by how apt the comparison seemed to be. There was this quote for example

“In their haste to be wiser and nobler than others, the anointed have misconceived two basic issues. They seem to assume: 1) that they have more knowledge than the average member of the benighted, and 2) that this is the relevant comparison. The real comparison, however, is not between the knowledge possessed by the average member of the educated elite versus the average member of the general public, but rather the total direct knowledge brought to bear through social processes (the competition of the marketplace, social sorting, etc.), involving millions of people, versus the secondhand knowledge of generalities possessed by a smaller elite group.

It is the knowledge problem all over again. But Orr, of course, never touches on it. His implicit model assumes a great deal of knowledge – known with a great deal of certainty – and it ignores the repeated failures of governments and bureaucrats even (or perhaps especially) when they were trying to take “the long view”). The real world is one in which we know – as individuals, even very able ones – remarkably little. And where frequent monitoring – what might in some abstract full-information world feel like “short-termism” – helps ensure appropriate course corrections, incorporating what we are learning. We have to build institutions around those realities – human societies have done so, over millennia. None of this features in the Governor’s world, even as he celebrates the vast lift in living standards over recent centuries, little of it down to wise and far-seeing bureaucrats.

After all, plenty of well-intentioned politicians and bureaucrats have thought they were looking to the long-term. The insulationist economic strategies adopted in New Zealand for decades after 1938 were conceived exactly that way, and didn’t end well. Think Big strategies in the early 1980s were certainly conceived with a long-term view in mind: they were an utter disaster all round. The idealists who passed the Resource Management Act thought they were consciously taking a long view. Globally, the Club of Rome people in the early 1970s were extremely well-intentioned and, for most practical purposes, totally wrong. And that is before we get to the wildly more extreme cases of those who thought they were building the “new Jerusalem” (so to speak) in revolutions and Communist takeovers in Russia and China. Hitler, arguably, had the long-term in mind and it would have better for everyone if he’d settled for fixing the short-term challenges Germany faced in 1933.

But Orr acknowledges none of this as he airily asserts that the biggest problem the world economy faces in “short-termism”. Arguably, one of the problems the New Zealand economy faced in the last decade was a Reserve Bank that wasn’t short-term enough in its focus – convinced it knew where interest rates “needed” to head back to one day, they quite unnecessarily left tens of thousands of people involuntarily in the ranks of the unemployed. And yet the Governor has praised their stewardship through that period.

It is a long speech and I’m not going to try to unpick every paragraph, but I did think it was worth picking up a few excerpts to highlight the shallow and reactive leftish thinking on display from one of our top public servants. Among his list of “challenges”

Environmental degradation, with climate change now well accepted as a significant impact on economies worldwide. The impacts are physical through nature, and financial through changes in consumer and investor preferences, and regulation.

Perhaps the Governor hasn’t noticed that in most advanced countries air pollution, and often water pollution is (a) far less than it was 100 years ago, and (b) is far less than it is in emerging economies (notably China and India)? And if he thinks climate change is having a “significant impact on economies worldwide” it might have been nice to have suggested a source. Recall that the OECD – about as centre-left technocratic a group as they came – suggest a modest impact over even the next 40 or 50 years.

Ageing populations are also dominating the outlook for the next 30-plus years, with Japan being the canary for us all to watch. Their population is on the decline due to their demographic profile weighted so much to the elderly. Savings and consumption patterns are changing simply due to this population swing. The older have the savings and are demanding less in goods, but more in services, especially human contact. Loneliness is a significant and growing disease. Yet the owners of capital are struggling to create careers out of caring for the elderly, at least at incomes that attract and retain the people needed. The same could be said for tourism in New Zealand.

Has “loneliness” ever featured in a central bank Governor’s speech before (it appears twice in this one)? If not, it would be for a good reason – central banks have nothing to say on the subject. Is there any substance to a sentence suggesting that a fall in the population is “due to” their demographic profile. And what on earth do the last two sentences mean? When willing labour is scarce surely (a) prices tend to rise, and (b) there is a substitution in favour of more physical capital?

And then there is inequality — the great cause of the left.

What do I mean by inequality? Well, even if the economic ‘pie’ has grown in total, the rewards are always skewed one way or another. Over recent decades, the rewards to the owners of capital (profits) have outstripped the owners of labour (wages) more than throughout economic history.

What does the Governor mean here by “skewed”? He doesn’t tell us. But he claims, or so it seems, that the labour share of income is somehow doing worse (levels or changes) that at any time in history. Even if it were true, we might expect a more careful analysis of why, and the implications of such a change. But here is chart I ran last year using OECD data of the labour share of GDP.

It is a remarkably variegated experience. And if one were take a more recent period, the labour share of income here has increased a bit since about 2001 (not entirely surprising given that (a) employment has been quite strong and investment weak, and (b) that wage increases have increasingly run ahead of near non-existent productivity growth.

Or one could add, in a New Zealand specific context, that to the extent that inequality has widened much at all in recent decades, much of it is down to housing costs, in turn the direct result of choices (ostensibly long-term in nature) of officials and politicians. Consumption inequality seems to actually be less than it was (chart in this link).

You might expect a senior New Zealand public servant opining openly, from his taxpayer-funded pulpit, about what is wrong with the world to actually know, and address, some of this stuff.

After all, in what is clearly a theme of elite official opinion in New Zealand at present, we should, Orr thinks, lead the world.

But, we do have opportunities to lead the globe in positive change if we can become more long-term in our economic activity.

Or

The great news is we are small, young of nation, lightly populated, green, kaitiaki (caretaking) of spirit, not dependent on the export of fossil fuels, and have a strong rule of law and sound moral compass. Significant and bold leadership is in our grasp.

This from the little country whose leaders have let it fall so far behind the rest of the advanced world in productivity – what opens up so many other options and choices – in recent decades? (And, re those fossil fuels, personally I’d swap Norway’s economy for ours any day).

But that isn’t a problem for Orr. He reckons the productivity failure is easy to overcome

The reasoning behind the low productivity is well understood but, apparently, difficult to combat in a coordinated, persistent, manner.

So with problem identification and solutions outlined, wouldn’t we just move on to resolution? Short-termism challenges us always and everywhere.

Appparently everyone agrees on (a) the analysis, and (b) the answers. All we need is to abandon short-termism. The superficiality of all this, the detachedness from reality – hasn’t he noticed that there is no agreement at all on what the nature of the problem is, reflected in quite varying policy prescriptions – almost beggars belief.

There is more glib stuff later (amid some odd Maori mythology) about how long-termisn will be our saviour

If company boards and managers have a long-enough horizon, then there are no externalities – all issues are endogenous to their actions (eg, pollution, employment, inclusion, and sustainable profit).

This is simply nonsense. Externalities don’t arise because people – in this case the agents of company owners – don’t have a long enough horizon, but (largely) because property rights and interests aren’t always clearly or properly assigned. And you can have as a long a horizon as you like and still often, probably repeatedly, be wrong. And if you want to worry about the long-term, I’m really glad that no one much 100 or 200 years ago worried very much about notions of global warming etc. Had they done so our current global prosperity would simply not be. Here is a nice line from a recent speech by the (greenish) chair of the Productivity Commission

British Economist Dimitri Zenghelis draws attention to the astonishing lift in global living standards since the onset of the industrial revolution (Zenghelis, 2016). The combustion of fossil fuels has been integral to that transformation and, in his words, “capitalism was founded on carbon”.

And we should be thankful for that, even as there may now be adjustment challenges.

I wanted to conclude with a couple of examples of Orr’s thinking on matters a bit closer to his core areas of responsibilities. There was this, for example,

We can also be unpopular with wider New Zealand, as shifting interest rates and/or implementing and altering the loan-to-value ratio that banks are allowed to lend at, are often not immediate vote winners. These activities directly cut across our human instinct for instant gratification, despite in the long-run maintaining a stable financial system and reducing the scale of financial volatility and/or crises.

And yet neither Orr, nor Wheeler before him, has shown any evidence at all that New Zealand banks were lending inappropriately, or borrowers were borrowing unwisely when five years ago the Reserve Bank intervened in a functioning housing finance market – where the banks had just come through a nasty recession unscathed – to stop willing borrowers and willing lenders getting together to assist people into a house. It was well-intentioned I’m sure – so many things are – but mostly what it looks as though it achieved was to keep ordinary New Zealanders out of houses a bit longer than otherwise, in favour of cashed-up buyers who got slightly cheaper entry levels. Ah, but Orr (and Wheeler) know better what is good for you and me.

And then this from the second to last paragraph

We still concentrate most of our investment in housing equity – rather than productive equity – relying on leverage from offshore borrowing. This is not a formula that will create ‘capital deepening’ in our economic efforts.

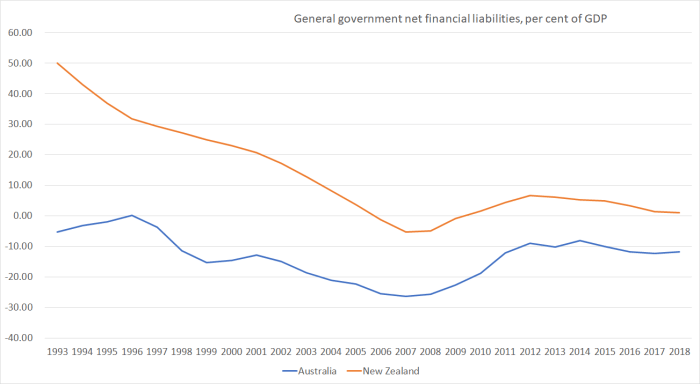

It is a popular line (echoed often by the Minister of Finance), but no less incoherent as a result. A Governor of the Reserve Bank really should know better. What is implicit in what he said there is that there is too much housing in New Zealand (“we concentrate most of our investment in housing equity”). And yet most people think that, given our population growth, too few houses have been built, perhaps for decades. Given our population growth, more real resources probably should have been devoted to building houses. I imagine his defence will be something around the price of houses, but high prices of existing houses don’t divert any real resources anywhere (they mostly just shift wealth from younger people to older people – each new loan creating a new deposit. As the Governor will be well aware through the latest surge in property prices over the last five years, New Zealand net international investment position (loosely, borrowing from the rest of world) has been shrinking as a share of GDP.

We deserve much better from our central bank, and particularly from an individual entrusted with so much (specific) power as the Governor. He should stick to his knitting – and actually get on and talk about pressing issues he is actuallly responsible for – he should stop championing personal political causes (even, or perhaps especially, if they happen to be music to the ears of the current government), and he should invest some time in thinking hard and rigorously about the claims and arguments he so readily tosses into the wind. Failing to do so will risk diminishing him, but (considerably more importantly) it will diminish the standing of the Reserve Bank, and mark another step in the decline of effective policy leadership from New Zealand government agencies.

Not everyone will agree though. I noticed a Letter to the Editor in this morning’s Dominion-Post from one Dave Smith of Tawa praising the Governor’s speeches (including this specific one) as a departure from the past pattern of “bland and uninspiring speeches”. But central banks are supposed to be about as exciting as the crash fire brigade at the airport. Leave the soaring rhetoric and the wider political vision to the politicians. Apart from anything else, we have some choice over them. We have none with Orr.

He is abusing, and degrading, his office.

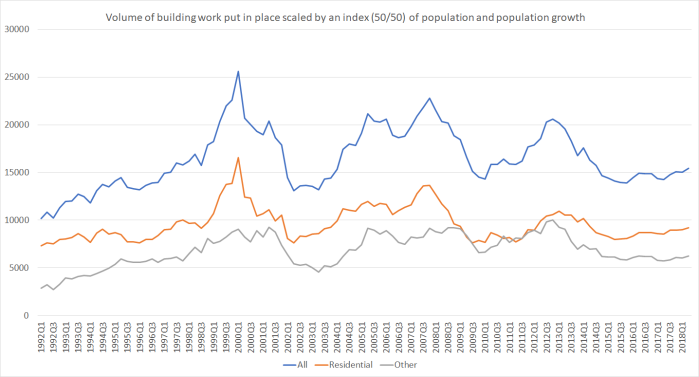

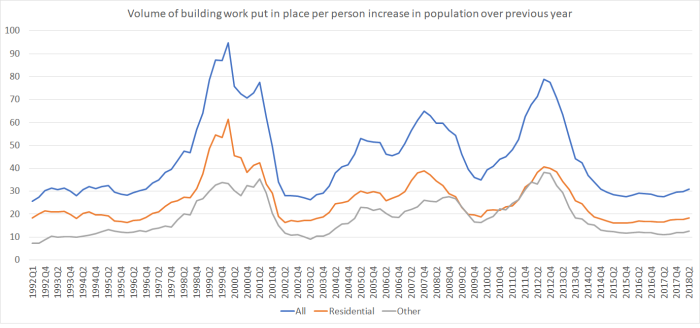

The peaks on this measure happen when population growth is at its cyclical troughs – unsurprisingly, since the normal base level of replacement and improvement work is still going on.

The peaks on this measure happen when population growth is at its cyclical troughs – unsurprisingly, since the normal base level of replacement and improvement work is still going on.