For small countries in particular, foreign trade is a key element in economic prosperity. Firms in your country develop products and services that people abroad want, and that enables your citizens to consume from the wider range of products and services the rest of the world has to offer. It isn’t just final products, but trade in intermediate goods and services (inputs to other production) also enables specialisation and the general gains from trade.

Foreign trade wasn’t always important in the islands of New Zealand. For the centuries after first settlement there was none. And (although not solely for that reason) the people – Maori – were poor. In modern New Zealand, foreign trade has been critical: 100 years ago there was a widely cited claim that New Zealand did more foreign trade per capita than any other country. Hand in hand with that, we were among the countries with the highest incomes per capita.

But no longer, on either count.

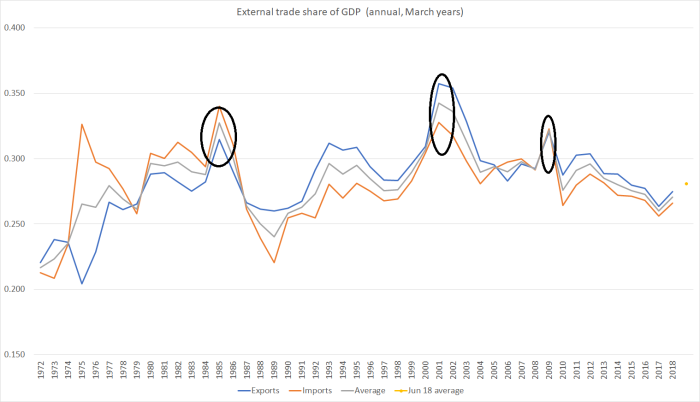

The latest quarterly numbers out last week did show an uptick in both exports and imports as a share of GDP. But here is the chart back to 1972 – annual data, plus the latest quarterly observation.

The foreign trade share has been, at best, static for almost 40 years (in most countries they’ve been increasing). The last few years have seen the trade share the weakest for almost 30 years (and the late 80s construction boom). I’ve highlighted the only three occasions when exports and imports have averaged 30 per cent or more of GDP: the year to March 1985, the years to March 2000 to 2002, and the year to March 2009. What was the common feature of those years? It wasn’t the stellar success of outward-oriented businesses. It was the (unexpected) severe weakness in the exchange rate: the devaluation of 1984, the period around the end of the dot-com boom when US interest rates were high, and New Zealand (and Australian) dollars were unattractive, and the international financial crisis (and extreme risk aversion) of 2008/09. Based on the rest of the set of New Zealand policies, those low exchange rates weren’t sustainable, and there was a relatively quick rebound.

What of other advanced countries?

Big countries tend to do less foreign trade (share of GDP) than small countries. That is no surprise, as there are many more markets and opportunities for specialisation (gains from trading) close to home. Here are the OECD countries that in 2016 (last year with complete data) had exports and imports averaging less than 30 per cent of GDP.

| Australia | 21.0 |

| Chile | 27.8 |

| Italy | 29.0 |

| Israel | 28.2 |

| Japan | 15.6 |

| Turkey | 23.4 |

| UK | 29.1 |

| USA | 13.3 |

Of them, Italy, Japan, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States are big countries and big economies. You’d expect to find them on this table, and if anything the anomaly is Germany, with a foreign trade share now in excess of 40 per cent of GDP.

Of the remaining countries, there are

- Australia, with five times our population,

- Chile, with more than three times our population, and with the second lowest labour productivity in the OECD (beating only Mexico), and

- Israel, which isn’t much larger than New Zealand but which – as I’ve highlighted here previously – has a similarly lousy productivity growth record.

And all, in one form or another, with severe disadvantages of distance.

There has been a tendency in some circles to excuse New Zealand’s low foreign trade shares by citing distance, but simultaneously a reluctance to take seriously what is implied by that limitation. If the opportunities for foreign trade from this remote location don’t look particularly good, isn’t there something deeply illogical (or worse) about continuing to use policy (as successive governments have done for last 25 years) to drive up our population – more people in an unpropitious location? All the more so when adopting that policy approach also involves driving the real exchange rate up, away from where it would likely settle otherwise. Not all New Zealanders suffer in the process – if you run a business geared, in effect, solely towards population growth you may well flourish – but New Zealanders as a whole have.

For all the occasional talk about rebalancing the economy (from both main parties, at least when they first take office) none of it seems to take any serious account of this constraint. Which is only set to become more seriously as – relative to other countries – the opportunities here shrink with the apparent determination to pursue net-zero emissions targets. Planting (lots more) is unlikely to be a path to sustained prosperity or higher productivity.

These days, New Zealand’s per capita foreign trade will among the lowest in the advanced world. Among the rich countries, only (very big) Japan and the United States will be materially lower than us. It isn’t a mark of a successful economy. But neither government nor opposition have any real strategy – or interest? – in turning things around.