On the Herald website yesterday morning, I noticed a headine “As an immigrant, I’m terrified of Winston Peters”. I ignored it, as clickbait. But it was still there last night, so out of curiosity I opened the story. The Herald is, after all, one of the main media outlets in the country, sometimes still approximating a serious newspaper, and immigration policy is one of the issues that, in a New Zealand context, I’ve given a lot of thought to.

With such a florid, emotionally overwrought, headline, I had low expectations of the article. But I still wasn’t prepared for what I found. The author, Ben Mack, is described as a “lifestyle columnist” for the Herald. His previous columns include a, borderline offensive, piece on “18 reasons why New Zealand is like North Korea”.

He’s an American citizen, and despite the headline isn’t really an immigrant at all. He is apparently here on a temporary work visa, having previously been here on a student visa. Quite how the economic prospects of New Zealanders would have been impaired by an apparent shortage of New Zeaaland “lifestyle columnists” isn’t clear, but set that to one side for the moment. Apparently he has hopes of eventually being granted New Zealand residency and staying on. Many do, but it isn’t an entitlement. When you go to a country to work on a temporary visa, you might well have to go home again – I know, I’ve done it three times. It is up to New Zealanders, and the New Zealand government, to decide how many people, and who, it allows to settle permanently among us. That’s not unusual. It is how pretty much every country in the world operates. I suspect Barack Obama might have been too conservative to Mr Mack’s tastes and preferences, but under the Obama Administration – as under the present US government – the United States grants one-third as many residence visas, per capita, as New Zealand does.

But, as a temporary resident in New Zealand, Mr Mack is apparently “terrified” by Winston Peters – a long-serving democratically elected member of a long-established Parliament. Why? Well, that isn’t really clear.

His article begins

Winston Peters is gaslighting the entire country. Sound extreme? If anything, I think it’s an understatement, actually.

The Oxford Dictionary defines “gaslighting” as to “manipulate (someone) by psychological means into doubting their own sanity.”

That’s exactly what Mr Peters is doing. And it’s long past time we did something about it.

I’m glad he provided a dictionary definition because I’d never heard of “gaslighting” myself. I still can’t say I recognise the phenomenon, And as for “it’s long past time we did something about it”, surely (a) it is called democracy, freedom of expression etc etc – all that stuff they don’t have in North Korea, and (b) the relevant “we” here is New Zealand citizens and voters (the latter category, even under our unusually liberal law, not including people on temporary work visas).

I get that Winston Peters isn’t everyone’s cup of tea (he isn’t really mine). In fact, only 7.2 per cent of voters opted for his party. 92.8 per cent didn’t. That’s almost as many as the 93.7 per cent of voters who didn’t opt for the Green Party. But, you know, it is democracy. I’m sure MMP is a strange concept to visiting Americans – and I’m not a fan of it myself – but it was the freely chosen system adopted by New Zealand voters. If you get 5 per cent of the vote, your party gets seats in Parliament. Personally, I think the threshold should be lower, but again the rules are the rules and one shouldn’t tamper with them lightly. New Zealand First has now been around for almost 25 years, and the high point of its electoral support was 1996, when the party got 13.4 per cent of the vote. And in a proportional representation system – and such systems are pretty common – it is rare for a single party to win a majority of seats in Parliament, and in the absence of a taste for “grand coalitions” – arrangements that undermine the potency of political opposition, a vital part of a parliamentary democracy – that means that at times smallish parties that could readily work with either main party can get to exercise quite a bit of clout.

But – and here is where a bit of perspective and experience of New Zealand might have come in handy to Mr Mack – not usually that much at all. New Zealand First was in coalition with National in the mid 1990s – Winston Peters as Deputy Prime Minister and Treasurer – and it was in partnership with Labour for a few years from 2005 – Winston Peters serving a Foreign Minister, and generally accepted as having done a reasonable job. And what changed? 1996 is a while ago now, but I can recall:

- a small increase in the inflation target, never subsequently reversed,

- free doctor’s visits for kids under six, never subsequently reversed, and

- a referendum on reform of New Zealand Superannuation, in which the cause Peters was advocating lost decisively.

Oh, and I think there was a Population Conference.

The 2005 to 2008 term was even less memorable, unless you were a Ministry of Foreign Affairs bureaucrat: their Minister secured them a great deal of additional money and the prospect of various new embassies.

I’m sure there was other stuff, but none of it was transformative.

Whether New Zealand First never made much difference because of Peters’ own limitation as a government politician or because he was always a minority party and legislation actually requires 61 votes, or some combination of the two, or other reasons altogether is an interesting question. But even if the opposition bark was in some way genuinely “terrifying”, the track record in office has been such as to not leave much trace.

Mack continues

Let me get this out of the way: I have zero respect for a man who, for decades, has made populist xenophobia his stock-and-trade, and who seems to delight in causing misery for entire groups of people (his abuse of the press – people simply doing their jobs like everyone else – is unacceptable enough).

I’m sure in journalism school they do – or did – encourage people to use words carefully. And when young journalists didn’t, grizzled sub-editors did it for them. But perhaps that discipline no longer exists? The Oxford dictionary – Mack’s own source – defines “xenophobia” as a ‘deep-rooted fear of foreigners’. Perhaps Peters does have that fear – I’ve never met the man – but I doubt Mack could produce any serious evidence for it. Instead, as with many pro-immigration people – be it the Greens, or the New Zealand Initiative – “xenophobia” has become a substitute for “thinking that, just possibly, one of the highest rates of immigration in the world might not always be benefiting New Zealanders”.

And I can’t say I have much time for how Peters handles the media but…..it is a free country.

Mack continues

What’s worse is his red herring that he’s “looking out for New Zealanders”, trotting out all kinds of nonsense about how us immigrants are supposedly pushing this great nation to breaking point.

He’s ignoring that it’s immigrants who have helped build this country. It’s thanks to immigrants New Zealand punches far above its weight on the international stage than a nation with fewer people than most big cities has a right to.

Actually, I suspect “breaking point” is Mack putting words in Peters’ mouth. But I really hope that all the politicians we elect – and those who sought office but missed out – could comfortably put their hand on their heart (although I guess that is more of an American idiom) and declare that they are, first and foremost, “looking out for New Zealanders”. A pretty basic expectation surely? Reasonable – and unreasonable – people might differ on what is in our best interests. That’s the stuff of politics. But I’m only interested in voting for parties that are interested in pursuing our best interests. I suspect all of them fit that bill, even if none align very well with what I personally think of as our best interests.

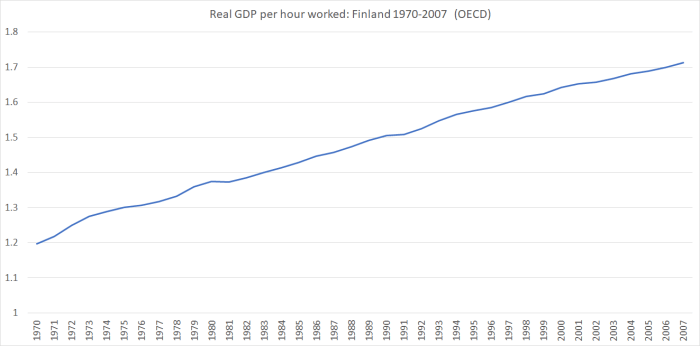

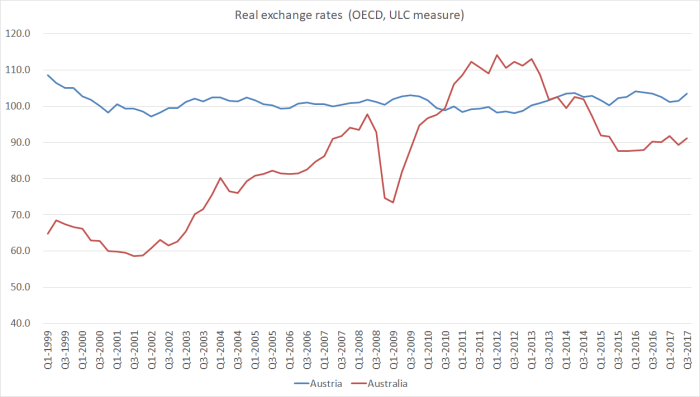

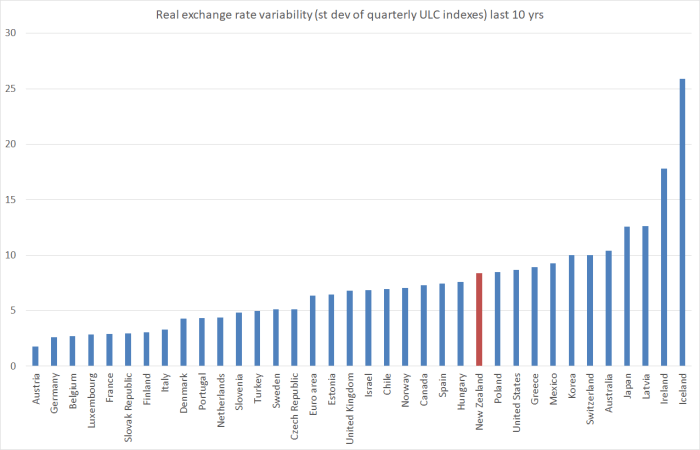

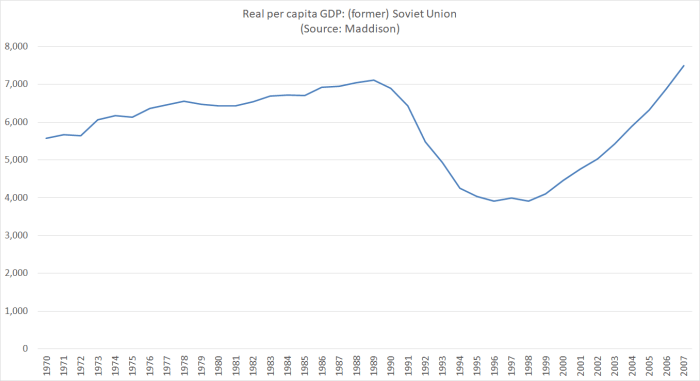

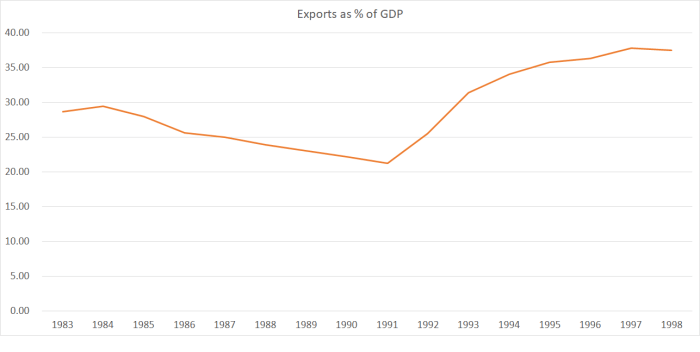

As for the second paragraph in that little excerpt, I have no idea what he’s talking about. I’m sure that some of those who’ve immigrated to New Zealand in the last 25 years or so – the current wave of large scale non-citizen migration – have made a great contribution. Most will have done well for themselves (if they hadn’t presumably they’d have gone home again), but in what way does Mr Mack think we now “punch above our weight” more than we were doing in 1990 (say)? In economic terms, we’ve slipped a bit further down the international league tables in that time. Hundreds of thousands more New Zealanders have left for the better opportunities they find abroad. Are our universities better ranked internationally? Our media more influential? Mostly, what has happened is that our population has grown rapidly and that, compounded with our crazy land use laws, have made housing ever more unaffordable. And New Zealand firms have found it ever harder to compete internationally.

It’s absolutely gaslighting when you look around and have no idea who is infected with New Zealand First’s noxious anti-immigrant extremism: Co-workers, classmates, friends, family, fellow shoppers at the supermarket, the clerk at the post office, the teller at the bank, the bus driver, the usher at the movie theatre …

Oh, no…..ordinary New Zealanders might share some unease about the rate of immigration in New Zealand. How unacceptable. Some economists do too. And here I’m not just talking about myself. Gareth Morgan- who seemed to draw his votes mostly from pretty left-liberal places and professional people – was expressing some unease too.

When you’re an immigrant like I am, you start to get a bit paranoid, wondering who might secretly want to see you forcibly removed from the country you now call home. Believe me, always having to be suspicious is incredibly damaging to your health and quality of life.

When you come on a temporary visa, you have no entitlement to stay. I quite get that worrying that the rules might change could be unsettling. But elections are like that, not just in respect of immigration but, for example, pension ages, water rights, taxation of capital assets and so on. Countries – their citizens and voters – get to make choices, and every choice has people on the other side of it.

And then the rhetoric rises to new levels of absurdity

It’s even more frightening when people with influence – like Duncan Garner recently – spout the same extremist views as Peters, then bizarrely claim it’s not xenophobic to say things like “immigration is great, but I’m not sure our traditional standard of living is enhanced by it”.

Yeah, nah bro. That’s dog-whistle politics 101. It’s the same kind of thing Hitler and the Nazis said during their rise to power. It’s the same thing the likes of Richard Spencer, Marine Le Pen, Alternative für Deutschland, Alex Jones, Milo Yiannopoulos and others spout with sickening regularity. It’s the kind of hateful rhetoric that has caused real harm.

It’s the kind of hate speech that can get people killed because it can inspire folks to physically attack immigrants.

Lets just state it simply: to prefer a low rate of immigration is not an illegitimate position. You might think, as I do, that a high rate of immigration to New Zealand has been quite economically damaging to New Zealanders. You might prefer social cohesion rather than ever-increasing cultural diversity. You might just prefer to live in a small, sparsely-settled country. Or you might just fear that politicians will never sort out of the housing market and the only way your kids will get a foothold, under say age 60, is if the population pressures (all policy-induced) are ended. They are all arguable views – some about evidence, some just about preferences. They are conversations societies need to be able to have among themselves, in a mutally respectful way. As a reminder, there is only one OECD country that actively aspires to take more immigrants than New Zealand does – and that is Israel, where the door is open to all (but only those) who share the Jewish faith and ancestry. The New Zealand status quo is exceptional, not normal. Perhaps it benefits most New Zealanders – I doubt it – but that is the issue that should be able to be debated.

Mack continues

You’ve heard it before, but it’s worth repeating again: many immigrants sacrifice literally everything to come to New Zealand for a better life. I am one of them. In coming here, I gave up a well-paying job with serious potential for career advancement at one of the largest news organisations in Europe (an organisation which took a chance on hiring me when I had a woefully skint resume and didn’t speak a word of German at the time).

I had a nice apartment in Berlin, enjoyed the luxuries of living on a continent where I could take a one-hour flight for as little as $30 to experience a completely new culture, and had close friendships with people I’ll never forget (all the more important when you’re like me and struggle with making friends).

To which my reaction is mostly “And……?” Yes, moving continents on a temporary work visas is a risk. Plenty of things in life are. And if you find it difficult to make new friends, sometimes staying at home makes sense. Recall, that Mack comes from a far richer country than New Zealand, and if by some chance he doesn’t end up getting residence – something he has no entitlement to – it isn’t clear why that is our problem.

What truly makes my blood run cold is now Peters has power. Make no mistake: Peters being “kingmaker” is the worst thing to happen to this country in modern times.

I am not exaggerating.

Yes you are. See 1996 and 2008. (And personally, I worry a lot more about politicians of all parties who for 25 years, after each election, have done nothing to reverse our slow relative economic decline.)

And he ends – after rants at the unfitness of office of the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition

A change in mindset is well overdue. When we watched the 2016 US presidential election with open-mouthed shock, many felt that such a thing could never happen here, that at least a dangerous figure like Trump could never gain power in the Land of the Long White Cloud. Guess what: it’s happened.

We need to galvanise our outrage and fear into action. As much as we might like to, we can’t ignore someone like Peters. His Trumpian style of bigoted nationalism is here, now. Instead, he must be repudiated at every turn. On panels. At press conferences. At political gatherings. At workplaces. At schools. Around dinner tables. Online. Everywhere.

If New Zealand wants to have a prosperous, less hateful future, it’s time to step up, now.

The lives of thousands of people truly depend on it.

The question is: what side of history do you want to be on?

I guess he’s new to the country, a temporary resident at this stage, but has he encountered the difference between a single decision-maker system (all executive authority in the US is vested in the President) and a system of Cabinet government? In whichever government emerges in the next week or so, members of the National Party or the Labour Party will hold either a majority of the positions, or all the positions. Perhaps Mr Mack could devote his political energies to securing change in his own country, where he is presumably entitled to vote.

What isn’t clear in any of this is what, specifically, in New Zealand First immigration policy Mr Mack objects to. I’ve written about it previously, drawing attention to the lack of any real specificity, and the lack of any real change to immigration policy when New Zealand First was part of government. Personally, I count that as a flaw, but it might be a reason for Mr Mack to consider toning down his hyperventilated rhetoric. At best – from the perspective of someone who thinks our immigration policy is much too liberal, whether the immigrants come from Ontario, Oregon, Bangalore, Beijing, Buenos Aires or Birmingham – we might end up with a system that reduced the average inflow to around the per capita rates Barack Obama was presiding over, in turn more liberal than the systems of many other advanced countries. But I doubt anything like that will happen, and New Zealand will continue its slow relative decline. Probably it will always be a nice place to live – if very remote. And while I’m not a fan of “what side of history do you want to be on” arguments, I’d prefer to vote for someone – if there were such a candidate – who was going to offer a serious prospect of reversing 70 years of relative economic decline for New Zealanders, and on building on the strengths that once made New Zealand one of the very richest and most successful nations on earth.

You might wonder why I bothered devoting so much space to Mr Mack. His views aren’t, in themselves, very important or, apparently, grounded in much understanding of New Zealand economic history or cross-country comparative experiences. But his column was published by one of our leading media outlets – supposedly more than just a portal for any view anyone wants to express. And it is inconceivable that the same outlet would publish anything so overwrought from someone on the other side of the issue ( and nor would I encourage them to do so). It is just the sort of contribution the New Zealand debate doesn’t need. But, of course, the strong suggestion in Mr Mack’s column is that he isn’t interested in debate, or dialogue…..instead disagreement, in his view, should invite ostracism.

There was a much better piece on The Spinoff last week from Jess Berentson-Shaw of the Morgan Foundation, encouraging serious debate and dialogue on immigration policy issues. I don’t agree with all of what she has to say – indeed, I suspect that when we got to the details of specific policies we might not agree on much at all – but it is a much more constructive, eirenic, approach to thinking about how a civilised society can grapple with complex and multi-dimensional issues, in this case immigration. She was prompted by the faux furore over Duncan Garner’s recent column

Discussing what we value and what matters in immigration will help. Having a decent framework for the issues that matter is a really good start, so let’s continue along this constructive track. I want to buy my undercrackers in a tolerant society that can talk more reasonably about this stuff.

I might come back to some of his specifics, and her links to a brief paper by Peter Wilson and Julie Fry on a possible framework for evaluating immigration policy.

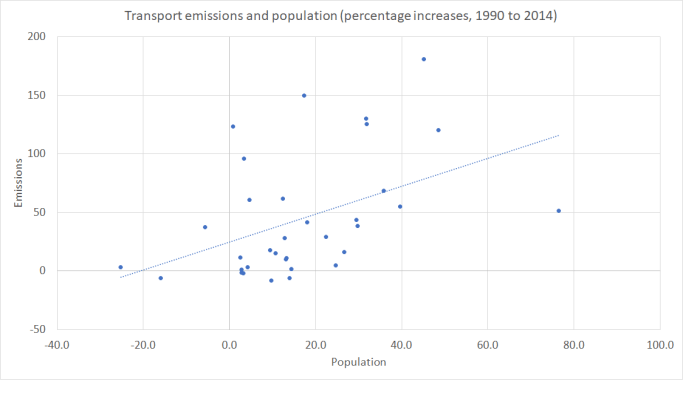

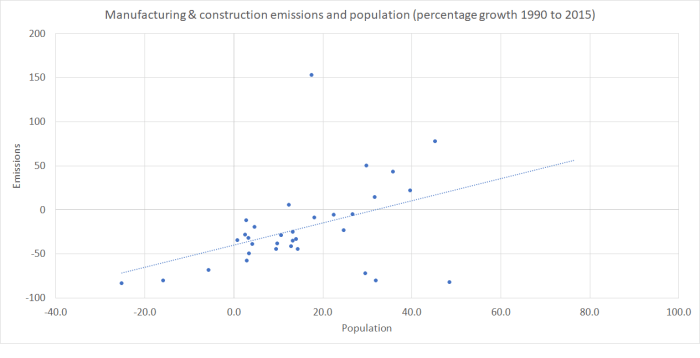

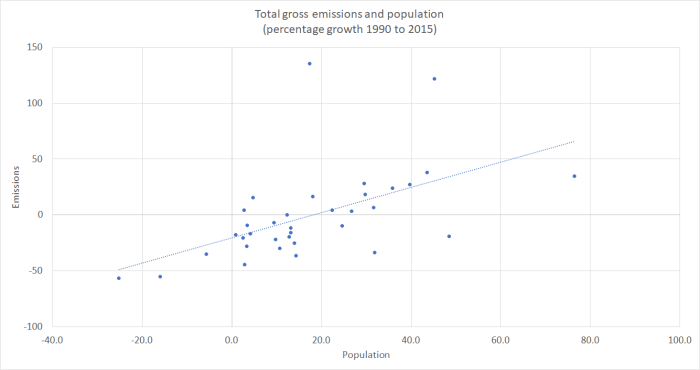

And finally, when I was responding to David Hall last week – who objected to any suggestion immigration policy and emissions reduction policy should be linked in New Zealand – I went back to read his introduction in the BWB Texts book Fair Borders. Having read that introduction several times, I’m still not quite clear what specific immigration policy he would favour for New Zealand. But I was struck by this brief comment

To echo an argument by migration scholar Alan Gamlen, if we cannot justify our migration policy while looking into the eyes of those it affects, we need to think again.

And, actually, I agree totally. But I wonder who doesn’t? (And actually the same comment could be made for all areas of policy.) There are many people who are at least emotionally sympathetic to an open borders approach who seem unable to conceive that there might be reasoned, moral, and defensible arguments for – following the practice of all states – and putting limits on who might come and settle among us. But I also suspect that in Hall’s quite “the eyes of those it affects” doesn’t include the New Zealanders who are already here. Economic prosperity and stable ordered societies aren’t mostly a matter of luck, but of consistent discipline and hard work over centuries. Successful societies need to guard what they’ve built – not in some in insular sense, closed to outside ideas, or even in some sense of “our wealth is at the expense of your poverty” (it just isn’t) – but because what is hard- and painstakingly built can be too easily corroded, put at risk, and eventually destroyed. They are particularly important economic considerations for an extremely remote nation with few obvious economic opportunities, which has already been in relative economic decline for 70 years.

And consistent with a story I’ve run here in

And consistent with a story I’ve run here in