There is plenty of talk about weak wage inflation, here and abroad.

Mostly, I have tried not to put too much weight on New Zealand wages data. I’m not always consistent, and higher nominal wage inflation is probably one of things we should normally be expecting to see if core inflation was really heading back to 2 per cent. But, one can’t really bang on about how there has been no labour productivity growth (reported by SNZ) for almost five years now, and expect much in the way of wage inflation. And I’m not one of those who thinks that immigration surprises tend to dampen wages (relative to GDP per capita, or productivity, that is): they may do so in certain specific occupational areas where there is a particular large presence of migrants, but generally – as New Zealand economists have believed for decades – immigration surprises add more to demand (including demand for labour) than they do to supply, at least over the first few years following a migration influx. With the unemployment rate still somewhat above most estimates of the NAIRU, one probably shouldn’t really expect much acceleration of wage inflation, but there isn’t any obvious reason why workers should be doing particularly poorly relative to the rest of the economy. Overall, of course, the economy isn’t doing that well; weak per capita GDP growth, and no productivity growth.

But listening to Steven Joyce talking about wages on Morning Report this morning prompted me to dig out and play with some relevant data.

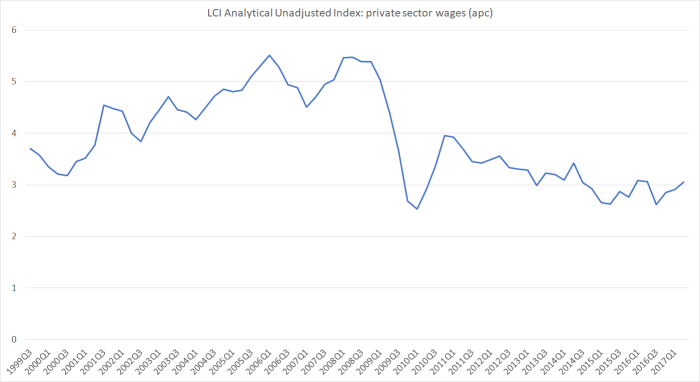

My preferred measure of wage inflation is taken from the Labour Cost Index. The LCI series that get lots of coverage purport to adjust for changes in productivity etc. I don’t have a great deal of confidence in the adjustment (mostly because it is a bit of a black box to outsiders), and so I prefer to use the Analytical Unadjusted Index of private sector wages (ie the data before the productivity adjustments).

It is a relatively smooth series. Wage inflation picked up a lot during the 2000s boom, slumped in the recession and after an initial recovery seems to have been tailing off somewhat since then.

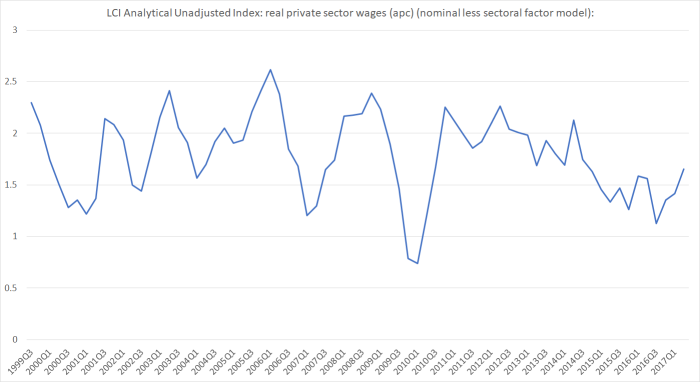

But this is a measure of nominal wages. And inflation is a lot lower than it was. Here is the same series adjusted for the Reserve Bank’s sectoral core factor model measure of inflation.

It is a noisier series (suggesting that perhaps parties bargain in nominal terms, rather than having reals in mind), although it is pretty unmistakeable that the average rate of real wage increases has been lower in recent years than in most of the earlier period. I could have done that chart with some smoothed moving average of CPI inflation but (a) lots of the short-term fluctuations in the CPI aren’t things that should affect wages (eg changes in ACC levies or tobacco taxes) and (b) doing so would actually only make the gap shown in the next chart larger and more striking.

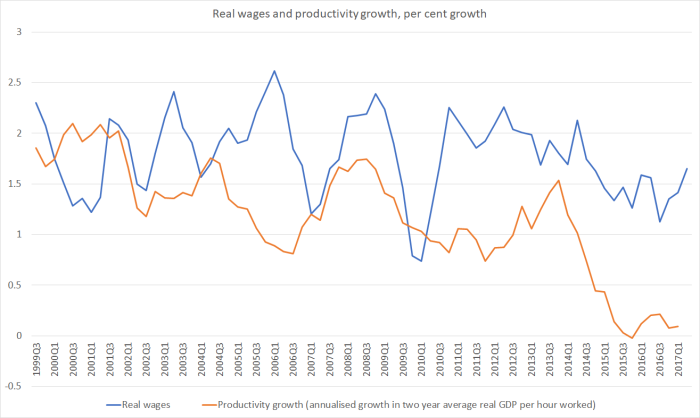

Over time, one might expect real wage inflation to roughly equal the rate of growth in labour productivity. Productivity growth is, by and large, the way living standards improve, and for most people real wages rates are an important element in their potential living standards.

One wouldn’t expect those relationships to hold in the very short-term. There are measurement problems in each of the series (wages, inflation, and productivity). There is also a great of short-term volat5ility in the published series that are used to generate the productivity estimates. And if labour is particularly scarce, or abundant, bargaining outcomes can easily differ for a time from what a productivity growth benchmark might suggest. Finally, a sustained lift in the terms of trade can also lead to real wages rising faster than real productivity measures.

In this chart I’ve shown real wages (same measure as above) and smoothed growth in labour productivity (real GDP per hour worked). I’ve taken the quarterly observations for the last two years, compared them to the quarterly observations for the previous two years (and so on) and then converted the result back into an annualised growth rate. There are plenty of other ways of smoothing the series, but none is going to change the fact that we have had no (reported) productivity growth for a number of years now. My particular measure provides a reasonably smooth series for productivity growth, consistent with my prior that to the extent inflation and productivity affect wage bargaining they are likely to do so in a smoothed or trend sense. Anyway, here is the resulting chart.

It hasn’t been a particularly close relationship over the (relatively short) history of the data. On average, real wage inflation (on this measure, although it is also true using a smoothed CPI measure of inflation) has grown faster than measured productivity over much of the period, perhaps consistent with the step up in the terms of trade from around 2004. (The remaining small upward biases in the CPI work in the other direction, understating real wage growth).

But the gap between the two lines at the end of the period is strikingly large and seems to have become quite persistent. Real wage inflation – although quite a bit slower than it was – still appears to be running much faster than productivity growth in recent years looks able to have supported.

If so, that represents a real exchange rate appreciation, representing a deterioration in the competitiveness of many of our producers. Looking ahead, and since we can’t count on the terms of trade appreciating for ever (for all their ups and downs, over 100 years they’ve been basically flat) we need to see some material acceleration in productivity growth or we are likely to see real wage growth falling away further still. For all the talk of moderate wage inflation in countries such as the US, not many countries (and certainly not the US and Australia) have had no productivity growth at all in the last five years. The puzzle in other countries may be why real wage inflation is so low, but here the focus should probably be on why it is still so high.