I was settling in for an afternoon of watching the gripping UK election results, when someone sent me a copy of a job advert that had appeared in Australia this morning. The advert was for the job of Governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. (It is also on the Reserve Bank’s website.)

It seems pretty extraordinary for the Reserve Bank’s Board to be proceeding with this process now. They were just getting underway with the search late last year, seemingly oblivious to the election, when the Minister of Finance told them to stop, and to nominate someone as an acting Governor. One of the conventions under which our system of government operates is that major appointments are not made close to an election. As the Minister of Finance noted, in announcing the acting Governor appointment

This will give the next Government time to make a decision on the appointment of a permanent Governor for the next five year term.

Since then we’ve learned that the current government has commissioned a report on possible statutory changes to the governance of the Bank. And the main oppositions parties have also confirmed that they favour changes, both to the governance and to the mandate of the Reserve Bank. Who knows which side will win, and what changes they would each make if they did.

But, clearly champing at the bit, the Board is already out with its advert. In fact, applications close on 8 July, which is a whole 10 or 11 weeks before the election. So the people who are brave or ambitious enough to apply actually have relatively little idea what they will be applying for. Will they be the single decisionmaker – a key dimension of the current model/job – or not? And even if not, will they just be presiding over a group of people they appoint, or something more Bank of England-like. Will they be charged with low unemployment or not? And so on.

Of course recruitment processes take time. But with an acting Governor appointed through to late March next year, it isn’t obvious why the Board couldn’t have put their advert out in late August, looking for applications or expressions of interest by the end of September. At least people considering applying might have a bit more a sense of quite what the role, as one part of overall New Zealand economic and financial management, might be.

The Board holds the whip-hand in the appointment process. The Minister of Finance can only appoint as Governor someone the Board has recommended (a candidate the Board proposes can be rejected, but then it is up to the Board to find another candidate). That is a very unusual model. In most advanced countries, the Governor is appointed directly by the Minister of Finance or the Cabinet. They can take advice from anyone they like, but aren’t bound by any recommendations. It is the way things work in Australia and the United Kingdom for example. In the US, the President nominates, and the Senate confirms (or not). In those countries, such mechanisms provide a high level of democratic control over an appointment which is hugely influential, over the short to medium term performance of the economy, and over the financial system. In New Zealand, the Governor is even more powerful – single legal decisionmaker – but there is very little democratic control over who wields that power. (The situation is even worse here if the government changes – the current Board were all appointed by the current government, and on average will tend to reflect that government’s interests/preferences/biases).

And so I’ve argued that the Opposition should quite simply state that one of the first pieces of legislation they would pass would be a short amendment to the Reserve Bank Act to remove the formal role of the Board in the process of appointing a Governor. It might be hard for them to do so – it could look like a power grab – but when our model is so out of line with international practice, any competent Opposition should easily be able to make the case. Promise to consult and take advice, for sure, but we should ensure that the elected Minister of Finance (and Cabinet) can do as their overseas peers can, and appoint as Governor someone in whom they have full confidence, not just someone the company directors appointed by the previous government wheel up.

What about substance of the Board’s advert? No doubt a person who fitted the profile might well be a good Governor, but there is a “walk on water” feel to it. Perhaps that isn’t uncommon with job adverts. What are they after?

- The ideal candidate will be a person of outstanding intellectual ability,

- who is a leader in the national and international financial community.

- The person will have substantial and proven organisational leadership skills in a high-performing entity,

- a proven ability to manage governance relationships,

- a sound understanding of public policy decision-making regimes, and

- the ability to make decisions in the context of complex and sensitive environments.

- Personal style will be consistent with the national importance and gravitas of the role.

- The successful candidate will also demonstrate an appreciation of the significance of the Bank’s independence and the behaviours required for ensuring long-term sustainability of that independence.

It is hard to argue too much with any of the individual items, although if I did I might wonder about:

- the emphasis on “outstanding intellectual ability”, but no mention at all of character or judgement. In tough times, and crises – a big part of what we have a Reserve Bank for – the latter seem likely to be more important than the former.

- they have clearly chosen to emphasise financial experience/standing rather than policy experience. It isn’t clear why an ideal candidate for this role – a New Zealand public policy and communications role – really would be a “leader in the international financial community”. That was, after all, what they thought they were getting last time.

- The explicit comment about personal style and gravitas was interesting. Are they suggesting that the new Governor might be more open to scrutiny and debate? If so, that would be welcome.

I was inclined to agree with the comment made by the person who sent me the advert that it wasn’t clear that any of the various names mentioned as potential candidates really fitted this description. Geoff Bascand, for example, would get a significant mark against him if they really want “a leader in the national and international financial community”. There would be other marks against Adrian Orr, David Archer, Murray Sherwin. Perhaps they are, after all, looking for an experienced banker? One thing that is striking is that there is nothing in the profile stressing knowledge of, understanding of, or relationships in, the New Zealand economy or financial system. That looks like quite a gap – and I reiterate my view that an overseas appointment, of a non New Zealander, would be untenable especially while the single decisionmaker system remains.

The final item on the profile list was particularly interesting.

The successful candidate will also demonstrate an appreciation of the significance of the Bank’s independence and the behaviours required for ensuring long-term sustainability of that independence.

It sparked my interest on several counts:

- first, I’ve never seen wording like it previously in an advert for the Governor’s position,

- second, it sounds really quite embattled as if the Board think that the Bank’s independence might soon be under threat, but

- third, and most importantly, just how appropriate is this? Parliament decides how independent or otherwise, in some or all areas of its responsibility, and it is the role of the Governor, and the Board for that matter, to work within the parameters that Parliament lays down. It isn’t the role of the Board to be seeking a chief executive who will advocate for a particular model of how the Bank should be run. After all, even if everyone agreed (as most do) that the Bank should have operational independence around monetary policy, and on the detailed implementation of prudential policy, there is a lot of room in between, where views and international practices differ. Should fx intervention be decided by the Governor? In some countries it is, and others not. Should regulatory policy parameters (eg DTI limits) be set by the Governor, or the Bank, or by the Minister? Again, practices differ, and so can reasonable people. It is quite inappropriate for the Board to looking to employ someone to defend all the powers Parliament happens for the time being to have assigned to the Bank.

- we should also be a little cautious about that wording “the behaviours required for ensuring the long-term sustainability of that independence”. Not only can the Governor or the Board not “ensure” that independence at all, but a variety of different types of behaviour – not all desirable – can be deployed contribute to that end. Not making life difficult for the Minister (of whichever party) is a well-known bureaucratic survival strategy. It won’t necessarily be the behaviour that would in the wider public interest. At the (perhaps absurd) extreme – but it is an FBI day today – J Edgar Hoover sustained his independence for the long-term in ways that were highly unseemly and not generally regarded as in the public interest.

Perhaps they just worded the advert badly, but it does rather betray a sense of a group of people who really aren’t suited for the role they’ve been given. They might be okay at monitoring the routine performance of the Governor. But you shouldn’t have control of the appointment to such a very powerful position in such hands at all – and, even while it is, they should have delayed this process rather than rushing so far ahead before the looming election.

UPDATE: For future reference (since the advert will be taken down when applications close) this is the advert

Governor

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (“the Bank”) is New Zealand’s central bank. It is responsible for monetary policy, promoting financial stability and issuing New Zealand’s currency. The current Governor is stepping down at the end of his term in 2017 and, accordingly, the Board is now seeking candidates to fill this vital and unique leadership role in the New Zealand economy. The Governor is appointed by the Minister of Finance on the recommendation of the Board.

The Governor is the Chief Executive of the Bank and a member of the Bank’s Board of Directors, and has the duty to ensure the Bank carries out the functions conferred on it by statutes, including The Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act 1989.

KEY RESPONSIBILITIES

The Governor is responsible for the strategic direction of the Bank and for ensuring that strategy is consistent with the Bank’s key accountabilities in relation to: price stability, the soundness and efficiency of the financial system (including prudential regulation and oversight, supervision of banks, non-bank deposit-takers and insurance companies, and anti-money laundering), the supply of currency, and the operation of payment and settlement systems. As Chief Executive, the Governor is required to lead a high-performance culture and ensure that the Bank operates effectively and efficiently across its wide range of policy, operational and communication functions.

CANDIDATE PROFILE

The ideal candidate will be a person of outstanding intellectual ability, who is a leader in the national and international financial community. The person will have substantial and proven organisational leadership skills in a high-performing entity, a proven ability to manage governance relationships, a sound understanding of public policy decision-making regimes, and the ability to make decisions in the context of complex and sensitive environments. Personal style will be consistent with the national importance and gravitas of the role. The successful candidate will also demonstrate an appreciation of the significance of the Bank’s independence and the behaviours required for ensuring long-term sustainability of that independence.

The role is based in New Zealand’s capital city, Wellington. Remuneration is commensurate with the seniority of the role and the New Zealand public sector.

Interested candidates may phone Carrie Hobson or Stephen Leavy for a confidential discussion on +64 9 379 2224, or forward a current CV to Lina Vanifatova before 8 July 2017 at lina@hobsonleavy.com

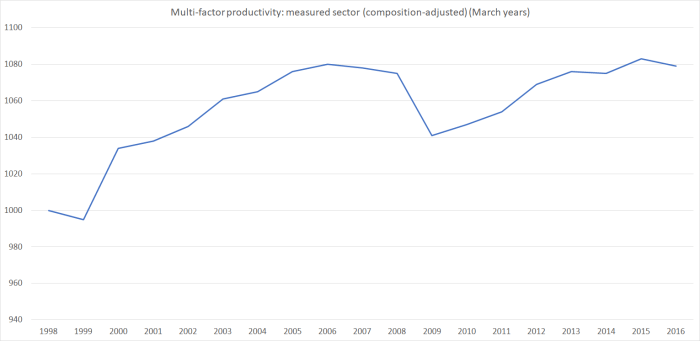

MFP measures are quite cyclical – if plant lies idle in a recession measured MFP will fall – but unfortunately the latest observations are only around the same levels reached a decade ago. There was no MFP growth late in the previous boom. There has been none since.

MFP measures are quite cyclical – if plant lies idle in a recession measured MFP will fall – but unfortunately the latest observations are only around the same levels reached a decade ago. There was no MFP growth late in the previous boom. There has been none since.

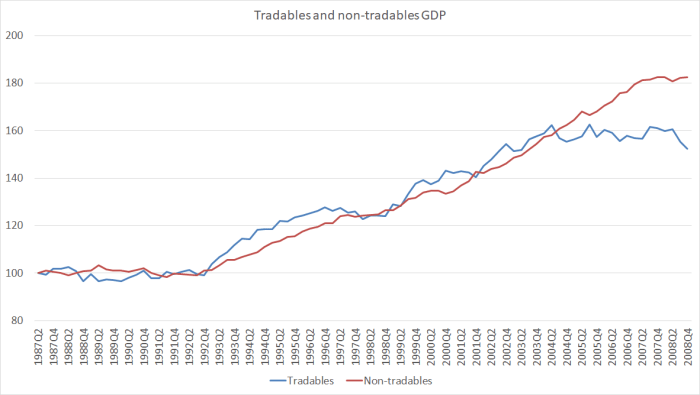

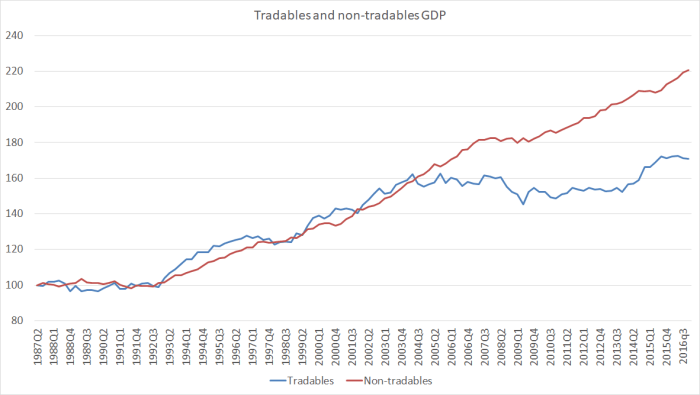

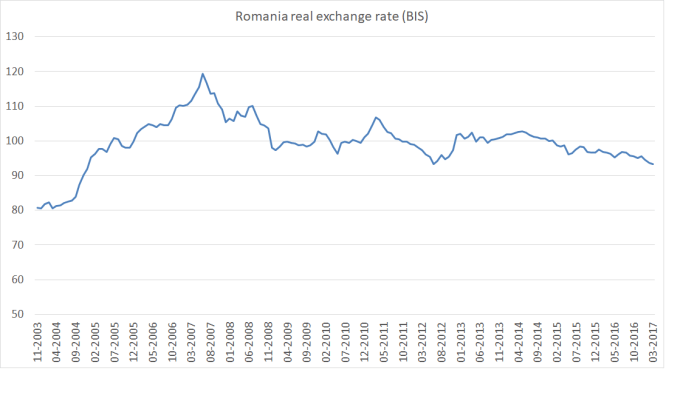

Real exchange rates aren’t things that ministers or governors directly control. They reflect the balance of (tradables vs non-tradables) forces in the economy. That balance here – still – makes it hard to manage much export volume growth from New Zealand.

Real exchange rates aren’t things that ministers or governors directly control. They reflect the balance of (tradables vs non-tradables) forces in the economy. That balance here – still – makes it hard to manage much export volume growth from New Zealand.

(You will recall that New Zealand has been going

(You will recall that New Zealand has been going