I’ve been a bit behind with my reading since I got back from holiday, but today was the first day of my son’s cricket season, and an opportunity for some concentrated reading on the sidelines.

The Productivity Commission released its final report Using land for housing last week. It is a long report (400 pages or so), and I’ve only read so far the 35 page summary version, and the first few chapters of the body of the report. From what I’ve read there are some useful specific findings and recommendations. But they come in a document that – as the Commission (with its rather Stakhanovite-sounding name) documents often do – puts altogether too much faith in government – the good intentions, knowledge, and capacity to execute of central government in particular. It was enough to prompt me to pull The Road to Serfdom off the shelf when I got home, as a bit of a counter to the over-confidence.

I haven’t read the whole report, and may want to come back with some more detailed observations later, but I suppose my overarching impression was of a report that was largely lacking in a sense of a positive role for markets, for the price mechanism as a reconciling and coordinating device, or indeed for the value of individual preferences. Markets work, and typically meet the needs of citizens when allowed to do so. Government planners not so much.

In its defence, the Commission would no doubt observe that they were asked not to undertake a fundamental review of the Resource Management Act (or, no doubt, the other relevant pieces of legislation). But I don’t find that sort of response particularly persuasive. The Commission shows no signs of unease with the concept of urban planning, and indeed seems to treat as wholly legitimate the choices of local councils to pursue particular visions of urban form (especially compact ones). It is simply those pesky voters who stand in the way of councils realising their visions. And perhaps worse, the ill-defined concept of “national interest” provides an overarching framework to the report. It is certainly true that local authority powers all flow from central government – ours is not a federal system – but the Commission seems to provide no basis to believe that central government will consistently establish better policy than local government. Is the track record any better? I’m not convinced. All sorts of governments – here and abroad – have defined all sorts of questionable things as being in “the national interest”. As I recall, it was an argument for the Clyde Dam. In some senses, this report was reminiscent of a report some worthy body might have written 50 years ago on making import licensing and exchange control work better – not entirely unworthy goals in their own right, but not really the point.

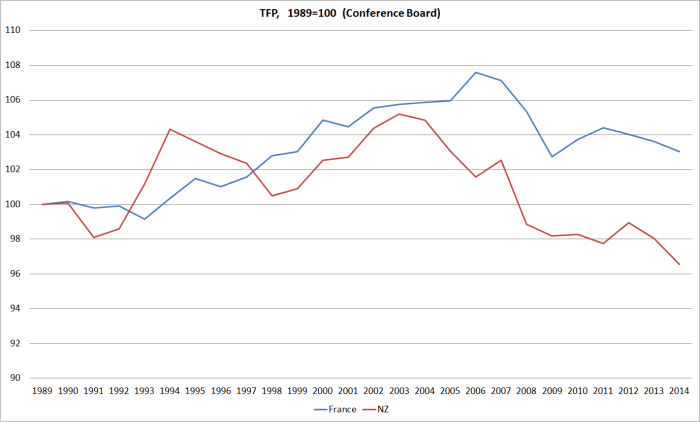

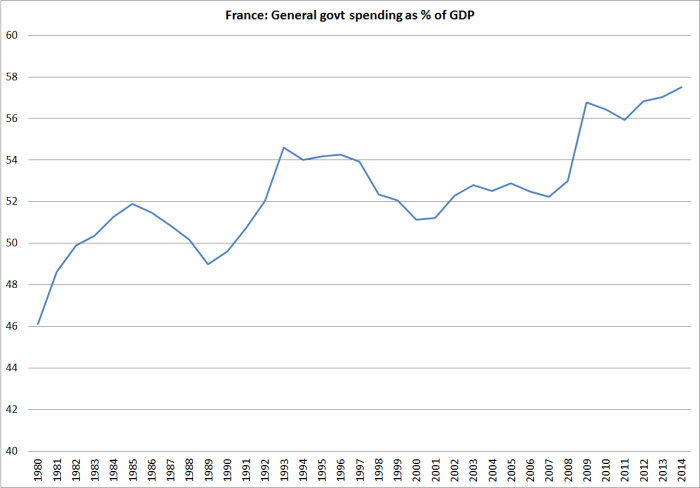

Part of this “national interest” story involves the Commission signing on all too easily to the idea that Auckland should get even bigger even faster than it already has. They do cite a single recent journal article about some modelling work done on several cities in the US (none of which makes up even 10 per cent of the population of the United States). Auckland, by contrast, already makes up a third of the total population of New Zealand, and since World War Two has grown faster than the largest cities in almost any other OECD country (Tel Aviv is an exception, and Israel’s economic performance has been about as bad as New Zealand’s). Scandalous as Auckland house prices are, is it really credible that the failure of Auckland to have grown even faster is – as the Commission strongly suggests – one of the largest conceivable explanations for New Zealand’s long-term underperformance?

And in neither its general tone nor in its recommendations is the Commission a friend of property rights, even though the land supply issues arise in the first place because central and local governments have severely restricted the ability of landowners to do as they like with their land. The Commission, for example, proposes legislation to time-limit covenants put in place between willing buyers and willing sellers in private residential developments. To what end? And, worse, they endorse the extension of compulsory acquisition powers to allow local authority Urban Development Authorities to take private land (at less than the value to the owner – by definition) for housing purposes. Again, wasn’t it central and local governments that created the problem in the first place? And now they want to further undermine the security of people’s interest in their own land, to enable Councils to pursue “their visions”. Even if such an approach were likely to prove helpful on the immediate issue (lowering urban land prices) in the short-term, how does the political economy of powerful urban development agencies look in the longer-run? Is it likely to be a model of good governance? Or is it more likely to be a channel through which vested interests (public and private) operate to benefit themselves, to the disadvantage of the public. In general, the report’s sense of political economy seems rather naïve. They are very taken with the idea that Councils operate at the behest of voters, who are disproportionately older and home-owning, but never really analyse alternative perspectives. Home-owners, for example, typically have children, but there is little sense of an intergenerational perspective in what I have read so far. And it has never been clear to me why the Commission thinks that middle-aged home-owners would have any problem with their Councils facilitating new housing developments on the fringes of cities provided that those developments covered the true marginal costs to the Council of such development.

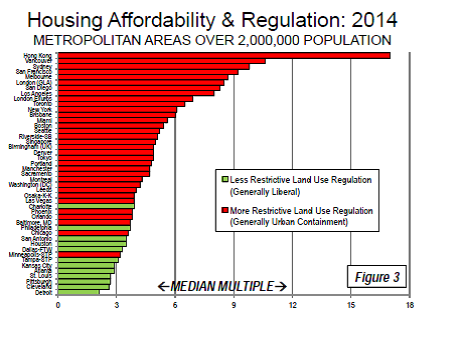

Finally, I was interested in the Commission’s description of the overseas visits they had undertaken. There were visits to Australia, and to the United Kingdom, but aren’t these the two countries with the most similar problems to those in New Zealand (at least as indicated by the Demographia price to income data)? No doubt there are interesting insights to be found in Australia and the United Kingdom, but the evidence suggests they have not gotten round to actually solving the problems. I was quite genuinely surprised that the Commission had not visited the United States and looked at the models that operate in many large and growing cities there, where house and land prices remain highly affordable (medians often under US$200000). It all seems to reinforce a sense that the Commission sees New Zealand’s urban planning not just as an unfortunate and costly feature we might be stuck with for now, but as something positively useful and appropriate. Doing so might be politically opportune in the short-term, but it is hard to see that it really deals with the longer-term issues in a durable and sustainable manner.

I may have cause to revise these comments when I’ve read the rest of the report, but based on the front window the Commission itself has put it up, I’m not optimistic of being able to do so. And that is a shame.