According to a new poll out this week, 93 per cent of New Zealanders want “financial literacy” to be a compulsory subject taught in all schools. The details of the poll don’t seem to be available, but we can probably assume that the questions were phrased in such a way as to encourage a positive answer. No doubt even a more balanced question might have drawn a positive response. To many it sounds like a “good thing”. I’m sceptical.

I’m sceptical at a variety of levels. First, and perhaps most practically, these surveys (and the reported views of advocates) never ask what people would prefer schools to stop teaching. There are only so many hours in the day/year. I’d face the same question as what should the schools stop teaching, but given a choice, personally I’d rather that schools were required to teach a sustained course in New Zealand and British/European history than that they teach so-called financial literacy. Kids are exposed every day to their parents’ attitudes to, and practices with, money and things. They aren’t directly exposed, to anything like the same extent, to maths, science, history, or foreign languages.

Second, as far as I can see, the evidence is pretty mixed as to whether teaching “financial literacy” makes any difference to anything that matters. Are countries with higher “financial literacy” scores richer as a result, more stable, happier? And a recent report (page 32) for our own government agency that deals with this stuff actually showed that, for what it is worth, the “financial literacy” of New Zealanders scored quite well in international comparisons. What is the nature of the problem?

Third, why would we expect that the government, and its representatives, would be good people to teach children about money? Perhaps we should judge people by their track record. The current Retirement Commissioner, as captured in this profile, does not exactly inspire confidence on that front (unless perhaps “do as she doesn’t kids”). And at a bigger picture level, in one way or another governments are the source of most financial crises – Spain, Ireland, Argentina, the United States, China. Governments are more prone than most to undertaking projects that they know provide low or negative economic rates of return. Governments face fewer market disciplines than citizens. And governments don’t have to live with the consequences of their mistakes. So perhaps I could support a civics programme that included a section on critically evaluating election promises and government policy announcements.

Fourth, much of the discussion in this area is quite strongly value-laden. And no doubt it has always been so. I recall the day when our 6th form economics class was visited by a banker, to try to promote savings etc. He brought along a hundred dollar note – this was 1978, and it was probably the first time any of us had seen one. Trying to set up a discussion about the merits of bank deposits (probably with negative real interest rates at the time), he asked us all what we’d do with the $100 if we had it. Various class mates rattled off their spending wishes, but the banker was totally flummoxed when one of my friends, a strong Christian, told him that what she’d do was to give it away. .

And where, for example, in all the discussion of financial literacy is there any reference to the findings that one of the best routes to financial security is to get married and to stay married? Finding the right spouse, and learning what is required to make a lifelong commitment work, is almost certainly a more (financially) valuable lesson that knowing that when interest rates fall bond prices rise. But it is not one we are likely to hear from the powers that be.

And fourth, this becomes an excuse for yet more bureaucratic/political bumf, reinforcing a sense that governments should have “strategies” about everything and anything. I was somewhat surprised to learn that our government has a financial capability strategy. Why?

Building the financial capability of New Zealanders is a priority for the Government. It will help us improve the wellbeing of our families and communities, reduce hardship, increase investment, and grow the economy.

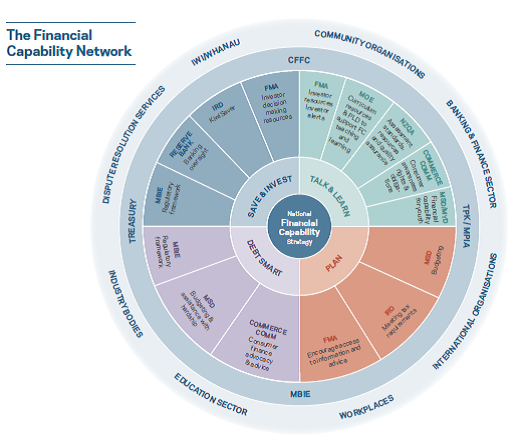

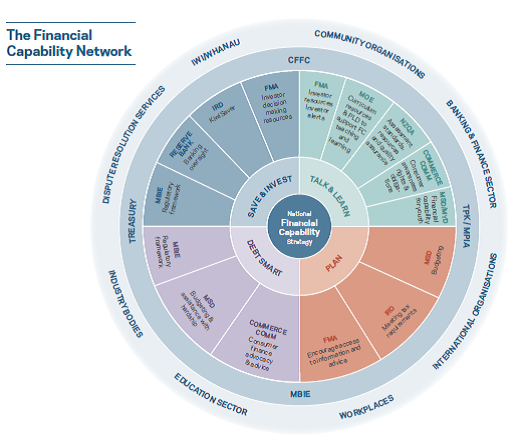

The National Strategy for Financial Capability led by the Commission for Financial Capability provides a framework for building financial capability. It has five key streams:

- Talk: a cultural shift where it’s easy to talk about money

- Learn: effective financial learning throughout life

- Plan: everyone has a current financial plan and is prepared for the unexpected

- Debt-smart: people make smart use of debt

- Save and invest: everyone saving and investing

On this measure, might we assume that “debt-smart” would mean taking as much interest-free student debt as possible and paying it off as slowly as possible? Not an approach I will be encouraging in my children.

More generally, I’m not sure that any of these items represent areas where we should expect governments to bring much of value to the table. One might marvel that human beings had got to our current state of material prosperity and security without the aid of government financial literacy/capability strategies. And since when has a traditional Anglo reticence about matters of money been something for governments to try to change? Better perhaps might be a focus on improving the financial capability of governments.

The Commission’s own research (p 26) shows what one might expect, people develop more “financial literacy” as they need it. So-called “literacy” is low among young people (18% of 18-24 year old males are “high knowledge”), who don’t need it much. It rises strongly during the working (child-rearing, mortgage etc) years (53% of 55-64 males are “high knowledge”), and then looks to tail off a little in retirement. All of which is unsurprising, and (to me) unconcerning.

I know the so-called Commission for Financial Capability doesn’t cost that much money, but as I’m sure they would point out, every little counts. The money they fritter away on national strategies and capabilities is money that New Zealanders don’t have to spend, or save, for themselves. In fact, this graphic, from the government’s policy statement, might suggest a few other government agencies that could be a trimmed back. Governments need to do well what only governments can do. So-called “financial literacy” isn’t obviously one of those things.

As an easy way into this, consider this US-government funded online quiz, a shop window for a US project on better understanding financial literacy. I imagine that most readers of this blog will score 5/5, while the average American scores 2.9. But then stand back and ask yourself why the average American (or New Zealander) needs to know the answers to these questions, phrased rather in the manner of a school economics exam. People who read blogs like this take for granted a knowledge of the answers, but in what way has that knowledge made your life, or mine, better?