If you have long since lost interest in my series of posts as to how Christchurch company director Rodger Finlay came to be appointed by the government as a director of the Reserve Bank (in its new governance model where the powers, including bank regulatory ones, rest with the Board) while, it was envisaged, he would keep on as chair of NZ Post, the majority owner of a bank (Kiwibank) the Reserve Bank prudentially regulates and supervises, and the spin around it, feel free to stop here. The title of the post was due warning. But sometimes you have to see things through to the end.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote here about (and excerpted) The Treasury’s incident report about the Finlay affair, and specifically the events that led to the Secretary to the Treasury providing a written apology to the Minister of Finance for the failure of her staff and organisation to explicitly draw to the attention of ministers the conflict of interest issues around Finlay’s appointments, either when he was being appointed to the Reserve Bank Board a year ago, or when Cabinet was agreeing to his reappointment as chair of NZ Post in June this year.

Yesterday I had two more OIA responses. Appointments to SOE boards are on the joint recommendation of the Minister of Finance and the Minister of State-owned Enterprises, and I had asked both ministers for material relevant to Finlay’s NZ Post reappointment (and withdrawal from that post) in June. Megan Woods had been the SOE minister responsible, but she apparently declared a potential conflict of interest, around her personal and professional relationships with Finlay, and so formal responsibility was shifted to Kris Faafoi (as it turned out, by the end of this he was in his last few days in office). Faafoi having left office, his papers on the issue are coming only slowly (early next year I’m told) but The Treasury did yesterday release the papers they had relevant to the appointment process Faafoi was involved in.

Treasury OIA response re acting Minister of SOEs and reappointment of Rodger Finlay as NZ Post chair Oct 2022

and Grant Robertson also provided his response to a similar request, but which also covered contacts with journalists on the Finlay appointments.

MoF OIA response re Rodger Finlay and the NZ Post board Oct 2022

In total there is about 50 pages of material

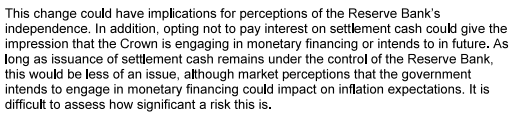

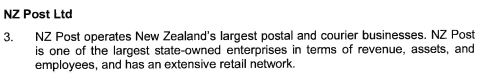

Taking the Treasury response first, there isn’t a great deal that is new. The relevant paper to the Cabinet Appointment and Honours (APH) Committee is included in full. It doesn’t note any conflict of interest issues (but we knew that from the Secretary to the Treasury’s apology and their report) but their description of NZ Post itself is a little surprising.

with no mention that NZ Post is also the majority owner of the 5th largest bank in the country.

I was slightly amused by what was, and wasn’t, kept secret about Finlay’s personal details

and the fussing around in the paper about whether the board was going to be suitably “representative”

But perhaps the point of substance was an email to Treasury officials from Faafoi’s private secretary on 8 June after the APH meeting noting that “Finlay’s reappointment went through APH today with no issues”.

While The Treasury had clearly been remiss in not including the conflict of interest issue in the papers, quite where were ministers (whether those proposing to make the appointment – and especially Robertson – or those deliberating on it)? Did it not occur to any of these people – either then, or when the RB Board appointment was made – to question whether it was really quite right to have someone responsible for bank regulation also chairing the majority owner of a bank. It is hardly as if Kiwibank’s ownership was a secret, and the APH paper does note that Finlay had been appointed as a Reserve Bank Board member (and from the Robertson bundle of documents we find talking points The Treasury had prepared for Faafoi, one (of a handful) of which explicitly states that he has been appointed to the Reserve Bank Board)? Or do conflicts of interest, real or apparent, just not matter to this government?

Most of the interest in the Robertson bundle is in the exchanges by members of his staff with various journalists about the Finlay issue.

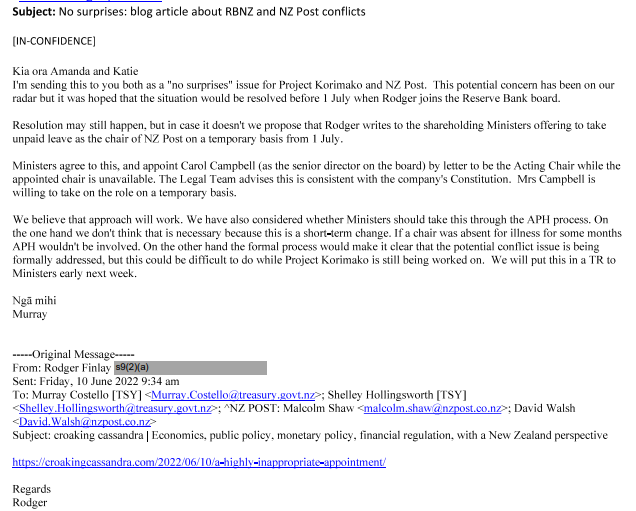

But there is also an email exchange on 10 June, the day my first post on the Finlay issue appeared. We know from The Treasury’s incident report that prior to 8 June (the day of the APH meeting) Finlay had approached Treasury suggesting that he could take leave of absence from the NZ Post role until the (then not known to the public) reshuffle of Kiwibank ownership went through – it had initially been planned, so the documents show, to have had this reshuffle wrapped up by 30 June).

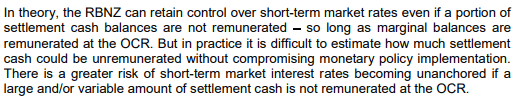

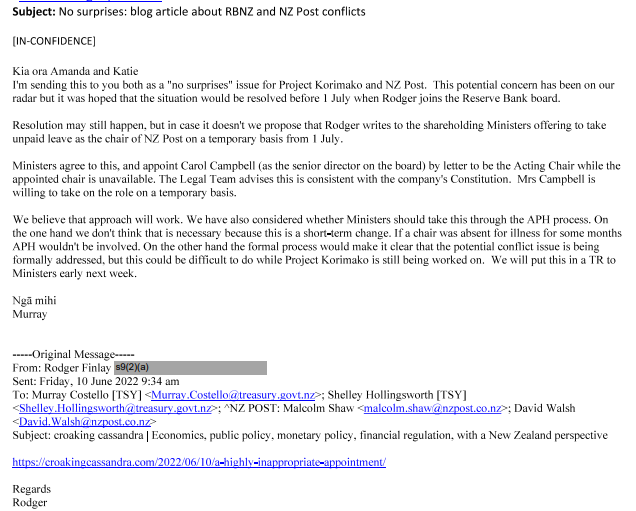

Anyway, on 10 June my post went out at about 8:30am (it is in my email inbox at 8:32) and at 9.34am Finlay himself sent a link to the post, without further comment, to four Treasury and NZ Post addressees. At 3:21pm, Treasury is emailing people in the relevant ministers’ offices, cc’ing the NZ Post people

I found it interesting that the official states “This potential concern has been on our radar” – what, just waiting for someone (whether me or another observer) to notice the egregious conflict involved in having the chair of the majority owner of a bank sitting on the governance board of the bank regulator? And so they suggest rolling out what Finlay himself had proposed – that he temporarily step aside from the NZ Post role – and had gone far enough to get the agreement of another director to act in Finlay’s place if ministers were to go with this option.

But that didn’t happen. The Treasury report says Finlay himself called the Minister of Finance, and the Minister took the view that as the potential conflict had been considered when the initial (RB) appointment was made and nothing had changed, there was no reason for Finlay to stand aside. Except, of course, that we know that the advice to Ministers and Cabinet in late 2021 had not mentioned the conflict, and neither had the advice to other political parties when, as the RB Act requires, they were consulted on Finlay’s RB appointment.

It is also pretty extraordinary – and this isn’t picked up in Treasury’s report – that there was no sign that these Treasury officials (or perhaps Finlay) really recognised the character of the Finlay conflict. He could have temporarily stepped aside as NZ Post chair and would still be responsible for bank regulation and supervision around Kiwibank during that period, and almost all regulatory decisions have effects longer than a few months standdown might imply. To address the conflict by means of temporary stand-down it would have to have been the Reserve Bank Board he stood down from, but the Reserve Bank role isn’t even mentioned here, and nor were Reserve Bank officials copied on the emails from either Finlay or Treasury.

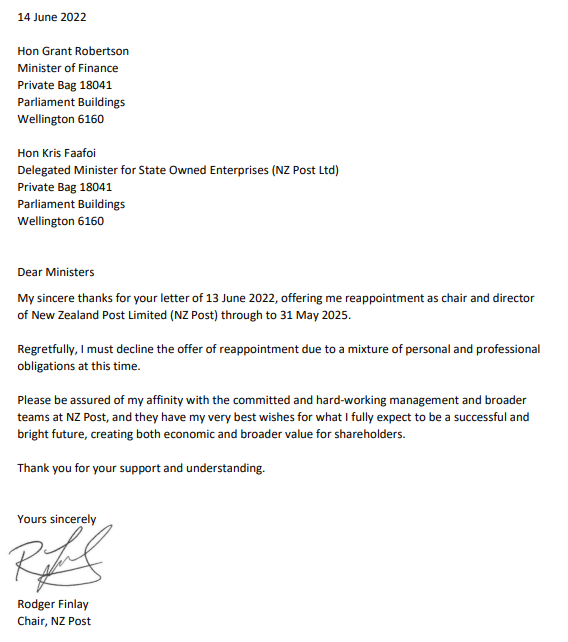

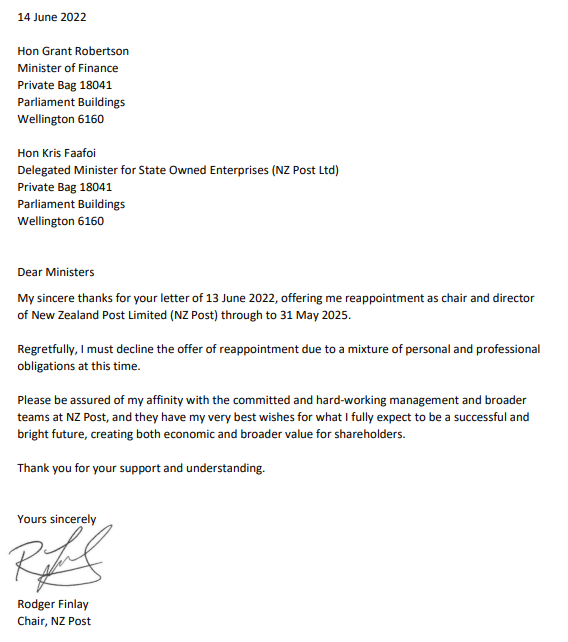

And so Cabinet went ahead and on 13 June reappointed Finlay for three years. And on 14 June Finlay wrote declining the appointment.

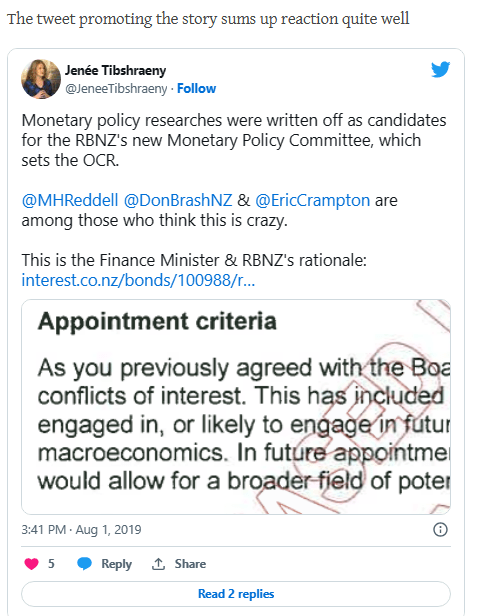

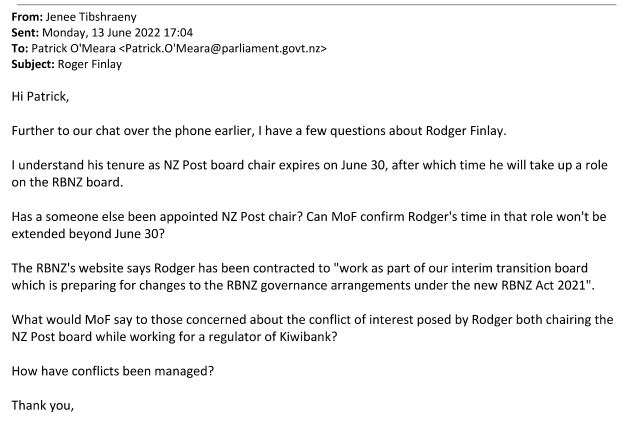

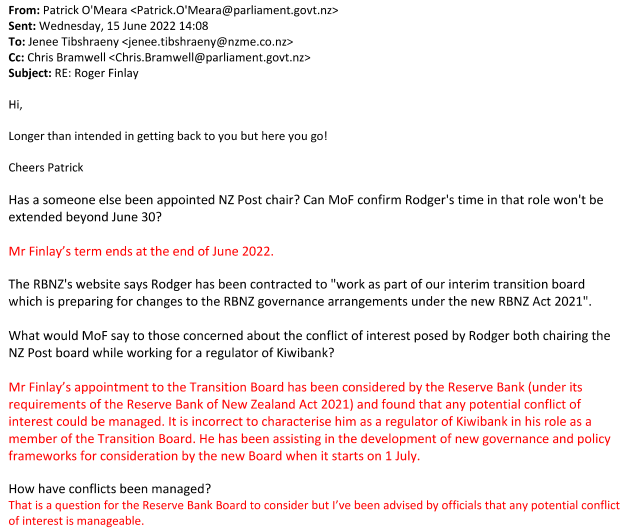

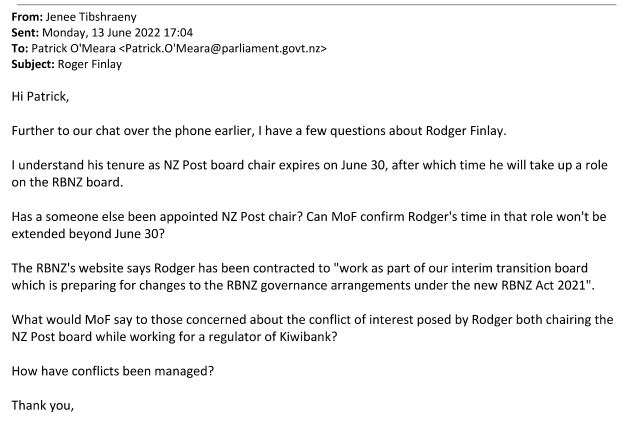

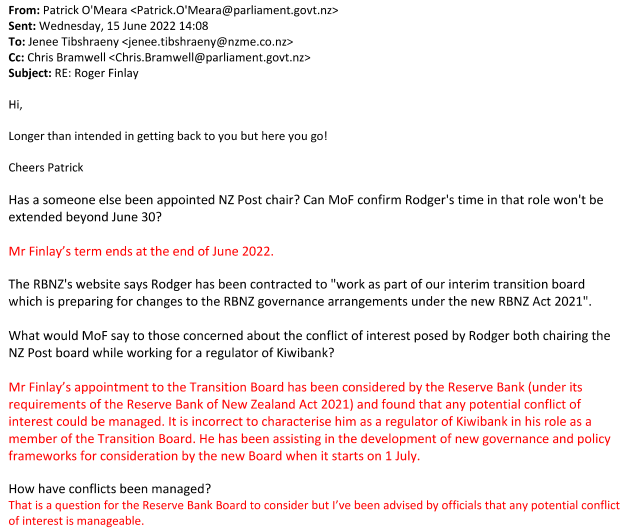

The first journalist to have asked Robertson anything about the Finlay issue was the Herald’s Jenee Tibshraeny.

At the time of this phone call and email, it was full steam ahead. Cabinet had approved Finlay’s reappointment and the letter of offer was going out.

It took the best part of two days, and multiple reminders, to get an answer out of Robertson.

The delay was convenient as by this time – and against the wishes of the Minister – Finlay had stepped aside, and finally personally resolved the conflict issue. Against that backdrop, the Minister’s answer to the Herald was pretty much active and deliberate disinformation.

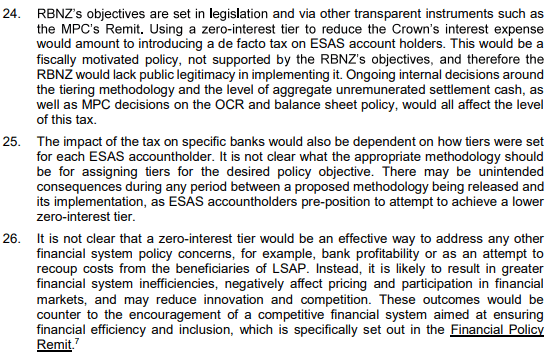

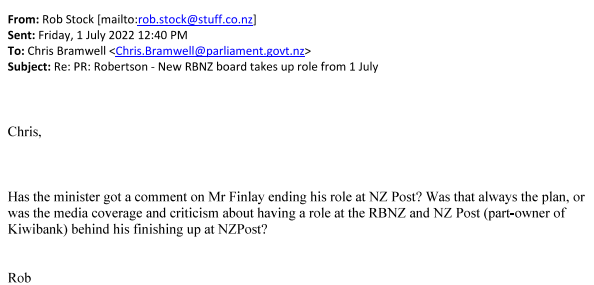

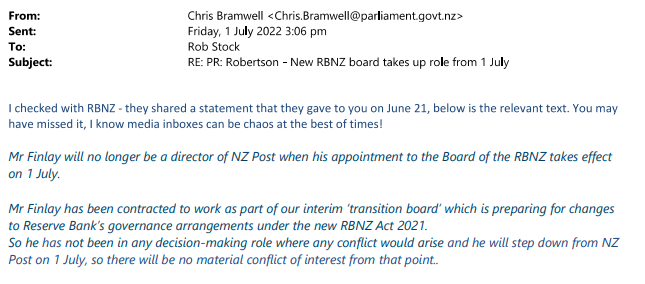

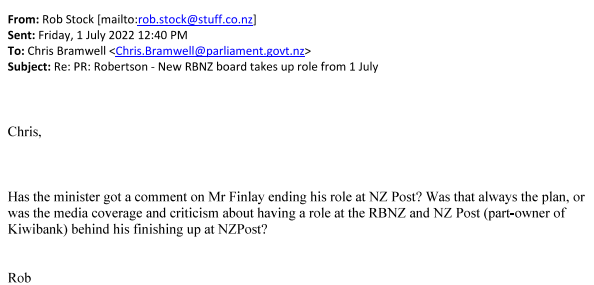

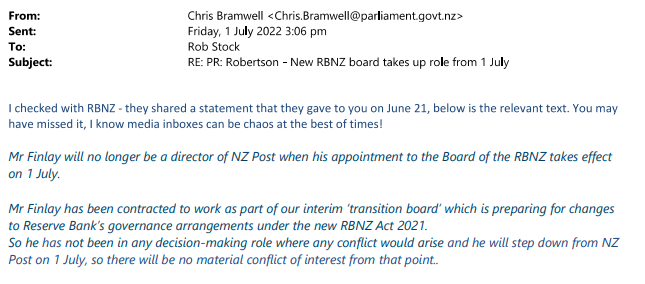

The next lot of media inquiries worth mentioning was on 1 July (the day after the rest of the new Reserve Bank Board was announced, including reference to Finlay as “previously” chairing NZ Post. Stuff’s Rob Stock asks Robertson’s senior press secretary

Who, in a series of email exchanges also engages in an active attempt to put the journalist off the trail (pretty sure the government would call this “disinformation” if anyone else was doing it).

First, the Minister was sick and couldn’t comment, but there was no news because Finlay’s term was due to end on 30 June. Stock responds that he didn’t recall either the RB, the Minister or Finlay “mentioning this was the plan for managing the conflict”, to which Bramwell responds disingenuously “I’m not sure if it was the ‘plan’…..you’d have to talk to Mr Finlay about that – or perhaps the RBNZ?”. Stock immediately responds (presumably of attempts to get others to comments) “No comment, not available, talk to Minister”. Whereupon Bramwell (for the Minister) again avoids answering the actual question with this response

Stock must have given up at that point. But if Bramwell’s last response was a non answer, it was nonetheless interesting since (a) it points us to Reserve Bank involvement in the political spin, and b) tells us that the Bank concedes that there may well have been “material conflicts of interest” from 1 July had the government gone ahead with its plans and Finlay not, at the end, done the decent thing.

There is a final rounds of exchanges between Tibshraeny and Robertson’s office at the end of August. These requests came after some earlier OIAs had begun to shed more light. You can read the exchange for yourself. On Finlay, the key question is “How was it ever ok for Rodger to be NZ Post chair and on the new RBNZ Board at the same time? [as the government deisred and intended]. Even [if] this would’ve been within the law [which it was] it surely would not have been within the spirit of the law”. There is never a straight answer from the Minister, just a deflection to the Reserve Bank who, she was told, concluded that “any conflict of interest…could be managed”.

Tibshraeny’s final question is about an issue I was not aware of until she identified it: that Finlay is a director of Ngai Tahu which now owns a 24.94% stake in Fidelity Life Assurance, an insurance company regulated by the Reserve Bank. That deal was not settled until early 2022 but had been agreed on before Finlay was appointed to the Board (and “transitional board”) late last year. That appears not to have been disclosed or discussed when his appointment was made. In Tibshraeny’s final email she notes “So, not great…..”

There have been so many issues to keep track of – including the other new director who when appointed was also on the board of an insurance company that for some reason was not regulated by the Reserve Bank (before there was a belated rethink and he resigned from the insurance company board) – and the Fidelity stake isn’t controlling so that on its own I can’t get too excited about it. But it does tend to speak to a pattern – running across all those involved here – that all that matters is the letter of the law, and nothing at all about the appearances, and the potential for actual or apparent conflicts. Finlay should, right upfront, have identified both the Kiwibank and Fidelity stakes as potential conflicts – and should never have put himself forward if he intended to stay on at NZ Post. In combination, they should have been disqualifying – to The Treasury and to Ministers.

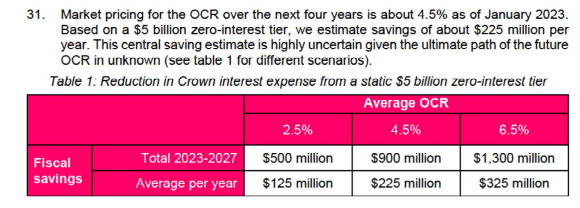

As far as I can see no one emerges very well from this whole saga, with some slight brownie points to Finlay who did after all finally step aside. The Treasury did poorly, perhaps so too did their recruitment consultants, the Brian Roche interview panel (for the RB roles) did really poorly (and that includes the head of APRA who sat on the panel), ministers did poorly (Grant Robertson most of all). No one called stop at any point, and all seemed to be focused (if at all) on the letter of the law rather than the substantive issues that mean it would not be acceptable anywhere to have as director of the bank regulator the chair of a majority owner of a bank.

But if any of these people or groups of people should have stood up and called a halt (before Finlay finally did), so too (and perhaps above all) so should the Governor of the Reserve Bank. the chair of the Reserve Bank Board, and all their attendant senior managers and Board colleagues. Every one of them should have known the conflict was untenable and unacceptable (it was the immediate reaction of a whole bunch of former central bankers after my first post appeared), and quite damaging to the credibility of the institution.

But if you have been following this story since June, you may have noticed that there have been OIA responses, fairly timely ones, from the Minister and from The Treasury, and nothing at all from the Bank (just references to them and their involvement in some of the other documents). It isn’t for want of trying.

On 1 July, the day after the full Board was appointed, I lodged with the Reserve Bank a request for

…copies of all material relating to appointments to the new Reserve Bank Board, including all material relating to appointments to the “transition board”.

Without limitation, this request includes all papers and other material generated within the Bank (other than of a purely administrative nature), any advice to/from or discussions with The Treasury, and any advice to and interaction with the Minister of Finance or his office on these issues.

It was directly parallel to similar requests lodged with the Minister and with The Treasury (both of whom responded substantively).

On 13 July, one of the many communications staffers got in touch to tell me

We have transferred your request to the Treasury as the information is believed to be more closely connected with the functions of the Treasury. In these circumstances, we are required by section 14 of the OIA to transfer your request.

You will hear further from the Treasury concerning your request.

I rolled my eyes – it was evidently a ploy (note I explicitly asked about material generated within the Bank, which other agencies would not necessarily be expected to have) and no doubt the Bank knew by then of my other requests – but did nothing more while I waited for responses from the Minister and The Treasury.

Having received those responses, on 3 September I went back to the Bank to renew my request (all on the same email chain, so there was no ambiguity about what the request was)

I am writing to renew my request. You transferred the request to The Treasury, but (as I’m sure you know) their release provided nothing on anything the Bank, its staff or management, Board or “transitional board” members said, wrote or did. I now know from the responses to similar OIAs to The Treasury and to the Minister of Finance, that the Board chair was involved in the selection of new board and transitional board members, Rodger Finlay (then a “transitional board” member) served on the interview panel for the second round of Board appointees, that RB legal staff had discussed issues around potential conflicts of interest for Rodger Findlay. Against that backdrop (and the media coverage of the Findlay situation in late June), it is inconceivable that there were no papers, emails or the like on any matters relating to the selection and appointment of Board members, whether or not such material was conveyed to The Treasury or to Minister.

That was almost two months ago. It was only yesterday I thought to check up on it and have sent them a note pointing out that I did not yet appear to have had a response. It increasingly appears as though the request will have to be referred to the Ombudsman.

But no doubt the Governor and his colleagues will keep on with the spin about being a highly transparent central bank. At this point, you really wonder what they can have left to hide, but perhaps the secrecy and obstructiveness is just some point of unprincipled principle?

UPDATE: About 40 minutes after this post went out I had an email from the Reserve Bank offering what appears to be a fairly abject apology for allowing this request to have fallen through the cracks, promising process improvements etc. Accidents happen, system aren’t foolproof (even with 20 comms staff), so I am inclined to take them at their word, but I guess it means I might finally get a response by Christmas.