I wrote earlier in the week about the as-yet unfilled vacancy in the office of Governor of the Reserve Bank. But there is also another significant vacancy that needs to be filled in the coming weeks, as the oft-extended MPC term of Bob Buckle finally comes to an end.

Buckle appears to be older than Donald Trump and has been on the MPC since it began 6.5 years ago. That means he’s been fully part of all the very costly bad calls ($11 billion of taxpayers losses when the MPC authorised the Bank to punt big in the bond market, and the worst outbreak of inflation in many decades, the consequences of which – notably in the labour market – we are still living with). And in his 6.5 years on the committee we’ve learned nothing at all of any distinctive contribution he may have made, we’ve heard nothing of his views (was he cheerleader, did he ever express any doubts etc?), there have been no speeches or interviews, he’s never apologised for or even acknowledged the bad calls (and their consequences) he’s been fully part of. And yet he has twice had his term extended (first reappointed by Robertson and was then extended again by Willis). He isn’t uniquely bad, and of the three externals first appointed back in 2019, when active expertise was deliberately excluded by Quigley and Orr, he was the least unqualified. But he is representative of all that is unsatisfactory with the Reserve Bank monetary policy governance reforms put in place in 2019. There is no accountability whatever, despite exercising huge amounts of delegated power.

Thinking about the vacancy, and the fact that it is now just over a year since Willis appointed two new, and apparently more capable, external MPC members prompted me to dig out the paper (“The Governance of Monetary Policy – Process, Structure, and International Experience”) that one of those new MPC members, (Prasanna Gai an academic at the University of Auckland but who’d spent a lot of time earlier in his career at the Bank of England), wrote in January 2023 as a consultant to the external panel reviewing the Reserve Bank of Australia. That review process that led to amended legislation and the creation this year of a distinct RBA Monetary Policy Board. It is a useful paper, easy to read and not long (28 pages), surveying experiences in a number of countries (including a quite sceptical treatment of the New Zealand MPC experience) and concluding with a couple of pages headed “Towards an ideal set-up” with six specific recommendations for the design of an MPC.

These were the recommendations

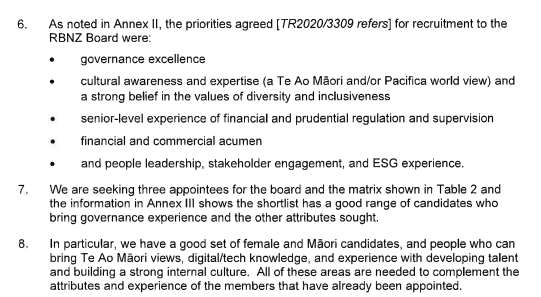

Recommendation 1: External members should be appointed through a merit based competitive process run at “double arms-length”, by a bi-partisan hiring committee appointed by the Treasurer that is diverse, experienced, and representative of society. Treasury Officials should be excluded from the MPC.

Recommendation 2: The threshold for economic expertise and policy acumen should be high. Members should be professional economists, with backgrounds in macroeconomics and financial economics, or offer broader experiences relevant to monetary policy. Gender, ethnicity, and industry diversity should be

important considerations in deciding the MPC make-up. Membership should be part-time with a commitment of around 3 days per week on average. Overseas members should be considered, subject to this time commitment.

Recommendation 3: The MPC should be relatively small (six). There should be two internal members and four externals. The role of Chair of the committee should rotate periodically and external members should be chosen for their capacity to serve in this regard. Pre-deliberation opinions should be sought, recorded (e.g. “dot plots”), and released to the public at an appropriate time. The chair should speak last and members invited to speak randomly. MPC members should be encouraged to interact with RBA staff between meetings.

Recommendation 4: The term of office be a single, non-renewable term of no more than five years.

Recommendation 5: To optimise information production and processing and to ensure democratic accountability, each member of the committee should “own” their decision and regularly explain their thinking to stakeholders at parliament and other fora. Members should have the freedom to dissent and MPC processes should be designed to diminish cacophony. Transcripts of the deliberation meeting should be released after a suitable lag so that stakeholders have a complete picture of the reasoning and debate behind the policy decision.

Recommendation 6: The MPC should be exposed to a regular schedule of external review by experts in monetary policy at 5-7 year intervals. These experts should be independently commissioned by the Treasury without consultation from the RBA, to avoid claims of partiality. The Treasury should take the lead in ensuring that review recommendations and insights are taken on board by the RBA and MPC.

Interesting food for thought, but anyone with any familiarity with the New Zealand system will recognise that list bears almost no relationship to what we have here (in law or in practice), except perhaps that odd “gender diversity” priority, which is pretty clearly what led Grant Robertson to appoint Caroline Saunders to the initial MPC (OIAed papers support that conclusion) and is probably why Orr appointed the otherwise utterly unqualified Karen Silk as the deputy chief executive responsible for macroeconomics and monetary policy, complete with a voting seat on the MPC. And, to be fair, there are some elements of Gai’s recommendations that I don’t agree with (including rotating the chair, bipartisan selection, and non-renewable terms).

One of the reasons I don’t like the idea of non-renewable terms is that serious accountability (ie with real and personal consequences at stake) is hard enough generally, but that the possibility of non-renewal is the most plausible point at which a monetary policy decisionmaker might face paying a price if they’d done poorly. Under the 1989 Act, the Bank’s Board was transformed into a body designed almost solely to hold the Governor to account, and they could recommend dismissal at any point if they concluded he was doing monetary policy poorly. The Board ended up so close to management (and for long periods was chaired by former senior managers), and had no resources of its own and limited economic expertise, that challenge was difficult. But, in principle, reappointment offered a chance, without too much awkwardness, to suggest that it was time for an incumbent to move on. The current Board still has some such role in respect of non-executive MPC members.

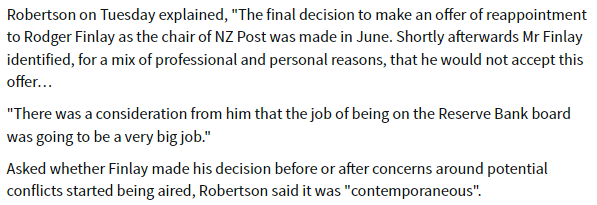

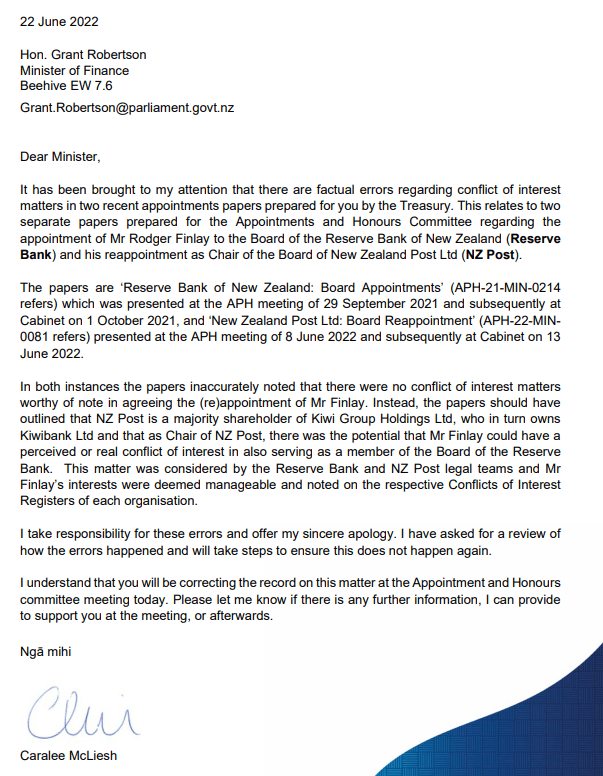

(The system was finally discredited in 2022 when, with all of Orr’s personal and policy failings already on display, the outgoing old board still recommended to their successors that Orr be reappointed, one of the worst public appointment decisions in New Zealand in quite some time, culminating in the engineered exit this year, barely two years into his second term.)

In formulating his recommendations, Prasanna Gai explicitly drew on a 2018 conference paper, (“Robust Design Principles for Monetary Policy Committees”) prepared for an RBA Conference, and written by David Archer (then a senior manager at the BIS) and Andrew Levin, a US academic but former Fed staffer. Archer, of course, had previously been chief economist and head of financial markets at the Reserve Bank until about 2004. It is another fairly accessible not-overly-long (16 pages) piece and they conclude with eleven principles, grouped as seven “governance principles” and four “transparency principles” (although I’m not sure I really buy the distinction). But like the Gai paper, it is very technocratic and rather weak on the place of a powerful central bank in a democratic society.

Reading the two documents together the thing I found most striking was that there was lots of talk (and they seemed to mean it seriously) about the importance of “accountability” (most explicitly in Gai’s recommendation 5 but strongly implicit in 3 and 6 as well). Archer and Levin are very much in the same vein (“Principle 6: Each MPC member should be individually accountable to elected officials and the public”). And yet, none of it seemed to involve any consequences whatever for the individuals. Both favour non-renewable terms so there is no potential discipline there, and Gai never ever seems to mention the possibility of removing an MPC member who had done monetary policy poorly. Archer and Levin are only slightly better, suggesting – in just a very brief reference not elaborated – that there should be “removal only in cases of malfeasance or grossly inadequate performance”.

I was a bit puzzled. One might expect serving central bankers to recite empty mantras about accountability that boil down in substance to not much more than having to publish a few documents and the Governor fronting up every so often to rather soft questioning at a parliamentary committee (in essence, the New Zealand model). But although each of these three authors had been central bankers none were at the time of writing.

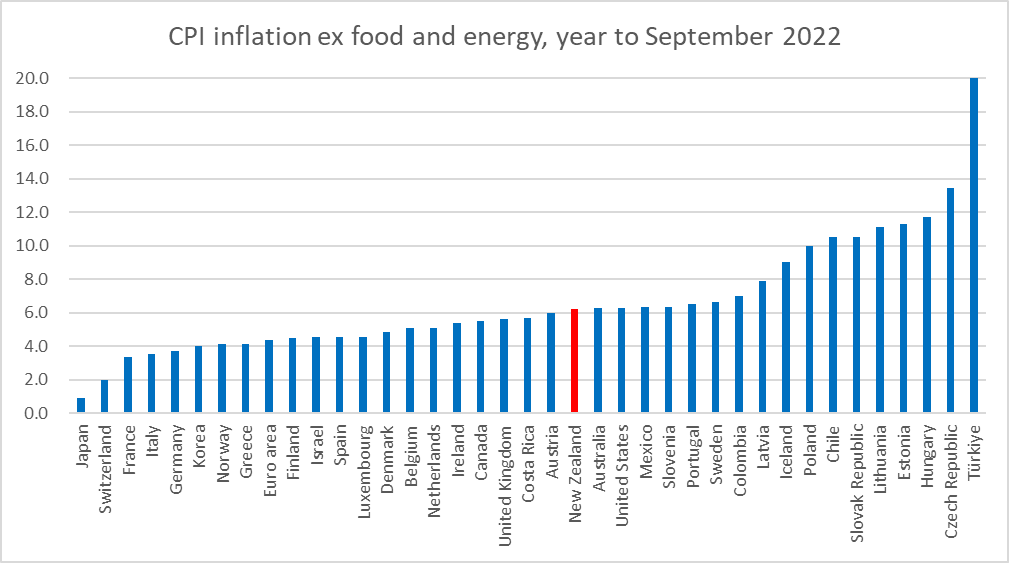

It was, perhaps, particularly surprising in Gai’s case. After all, he was writing in January 2023 when central bankers in a wide range of countries were revealed as having stuffed up badly (no doubt with the best will in the world) and Phil Lowe was under fire in Australia. I wondered if perhaps one factor for Archer and Levin had been that were writing in 2018 when we were several decades into inflation targeting and in most countries if there had been monetary policy errors in the grand scheme of things they were relatively small.

And so I asked David Archer (now retired) why their paper had not dealt in any detail with options for serious personal accountability. He gave me permission to quote from his response (prefaced by a “joint papers are a compromise”)

On making accountability real, I favour the ability to remove for policy failure reasons(a) where it is possible to define the objective with some clarity, and(b) where the procedure and protocols for assessing the bank’s/individual’s contributions to failure are fairly robust and shielded from political intervention.I think (a) is possible, since maintaining medium term price stability — a single objective, able to be stated numerically — is clear enough.I think (b) is more difficult. A previous NZ construction, involving a monitoring group that comprises outsiders who owe their duty to the public but that is able to peer inside the operation — that is, a board with independent chair and no management responsibilities — was a pretty good, though not perfect design. The imperfections were less in the construction than the execution, but the construction could still have been better — eg a requirement for an annual assessment report that requires a ministerial response and FEC examination.It is noteworthy that the ability to remove for policy failures is almost vanishingly rare internationally.

I agree with the spirit although not entirely with the details. In the end, I think that – in a democracy – decisions to appoint or to remove MPC members (executive or not) should be made by people who are elected (ie politicians) and thus themselves directly accountable. But it might be a reasonable balance to say that people could only be removed (for policy failure causes) on the recommendation of an independent assessment panel.

Unlike David, I think the old Reserve Bank Board model (while well-intentioned) was never likely to be an adequate approach. Operating within the Bank, with the Governor as a member, with a senior Bank manager as secretary, with no analytical or consulting resource of their own (to which one could add that they were required to review each MPS and see if it did the statutory job, which made it hard to stand back later and hold the Governor to serious account) it was never likely to succeed. Things got too cosy, the Board was more interested in having the Governor’s back, they held cocktail functions to help spread the Bank’s story, and to the extent there was challenge or questioning it was often on rather technical points rather than seriously attempting accountability. It might have been different if something like the Macroeconomic Advisory Council I used to champion had been set up, fully independent of the Bank and Treasury, and with serious analytical grunt itself.

Central bank monetary policymakers wield a great deal of power. There is no review or appeal process embedded. Being human, the best central bankers will make mistakes (just like the best corporate managers or corporate boards) and there needs to be a personal price to failure, otherwise we have given great power with little or no responsibility. If really big mistakes are not going to lead to those responsible being fired – or not even lead to them being not reappointed – we should rethink whether operational autonomy over monetary policy is appropriate at all. We still need expertise on these issues – as in so many other areas of public life – but there is no necessary reason why the decisionmaking power should be delegated. When politicians wield power we have the satisfaction of being able to toss them out when they do poorly. (And for those who worry about possible pro-inflation biases among politicians, a) for the decade pre-Covid we had the opposite problem (inflation a bit too low relative to target) from central bankers, and b) it is salutary to see how much “cost of living” now features among public concerns, here and elsewhere, even a couple of years after the worst of the inflation.)

To be clear, I am not suggesting that independent MPCs should be able to be second-guessed when they make their initial decisions (even if there had been a consensus in March/April 2020 that the MPC was going astray, Orr and company shouldn’t have been able to be tossed out then). But when outcomes go so badly off track, people should be removable and should not be reappointed. It can’t be a mechanical or formulaic thing – outcomes are always a mixture of specific policy judgements and unforeseeable shocks – but there is nothing particular unique about monetary policy in that (see the ousting of corporate chieftains when things go badly astray; sometimes it is just because there needs to be a scapegoat, somone seen to take the fall). But it does heighten the importance of making people individually responsible – speeches, interviews, proper minutes, attributed votes, FEC hearings and so on. It is hard to dismiss an entire committee – one of the 1989 government’s reasons then for choosing a single decisionmaker – but if a committee is doing its job at all well, some members will inevitably emerge looking better (or worse) than others. (Unlike our experts – above – I think there is a particular responsibility on the Governor, who controls staff analysis etc and is full time, but that isn’t an excuse for free-riding externals).

There is one area where we deliberately make it all but impossible to remove someone for bad substantive decisions: the judiciary. And that is probably as it has to be. But in the case of lower courts there are (layers of) appeal processes, and in higher courts finality is often the point (there may not be objectively right or wrong legal interpretations, but what the courts provide – subject to parliamentary override – is finality. And unlike most central banks, courts are unshamed about having majority and dissenting opinions, the latter often lengthy and thoughtful. There is no good reason for putting our central bankers on such a protected pedestal – mess up badly and face no personal consequences, no matter how much damage those bad choices have done to the country.

But to come back to the mundane, you have to wonder what Prasanna Gai makes of being an MPC member, operating in a model so much at odds with the analysis and recommendations he gave to the RBA review panel not much more than a couple of years ago:

- He was selected last year by a panel, appointed entirely by the previous Labour government, led by Orr and Quigley, who would have spurned his expertise when the MPC was first set up in 2019,

- The Secretary to the Treasury (or his nominee) is a non-voting member of the committee,

- The MPC is numerically dominated by internals, one of whom has no economics background at all,

- Not only is the chair not rotated, but it was held by a domineering personality, long observed to be intolerant of challenge and dissent, whose governorship finally flamed out when he completely lost his cool in meetings with, first, Treasury and then the Minister,

- MPC members have renewable terms (although I guess Gai could decline to seek a second term)

- There is no disclosure of individual member views, either in minutes or subsequently in speeches, interviews, or hearings (and in his paper Gai makes much of the free-rider problem/risk), and

- Despite having been in place for 6.5 years now, through some of the most turbulent times for decades, the only “review process” was run by the Bank itself.

To which, we might add, that Gai himself made a little history recently by actually doing a speech on matters relevant to New Zealand monetary policy to an outside audience. Which was good. Except that no text of that speech was made available, no recording of the question time was made available, and only those who happened to be in Auckland on the day could get one of the limited number of tickets. He and the Bank appear to have allowed the event to be advertised as offering exclusive access. Gai refused to entertain media questions either. Since the MPC Charter actually does allow members to make speeches, which are supposed to be readily available, he cannot even blame those choices on “the rules”. It doesn’t really seem like walking the talk.

It is a shame in someone who appeared to have a lot to offer that he seems to have adapted to the cage Orr. Quigley, and Robertson built, and which so far Willis has done nothing to overhaul. I strongly suspect he adds more value than Peter Harris or Caroline Saunders – and I valued my engagement with him in those pre MPC years – but for the time being they are observationally equivalent. For those who initially talked him up as a potential Governor – and noting slim pickings – it isn’t a great display of leadership in action.

Meanwhile it will be interesting to see what sort of person Quigley and Willis find for the Buckle vacancy. Recall that, like the Governor’s position, the Board proposes, but the Minister of Finance is quite free to knock back a nomination and insist that the Board comes back with someone better.