I’m not one of those inclined to join the new Leader of the Opposition in describing the government’s handling of the coronavirus situation as “impressive”, but sometimes other people are just determined the make the Cabinet and core government departments (notably Health, Treasury, DPMC) look not bad at all.

Transparency is one of those issues. I was critical – and still am – about how slowly the government released key official documents relevant to the crucial decisions taken at various stages in March and April. Difficult decisions made, inevitably, with partial information, and with consequences (either way) that are huge by the standards of any typical government decision should have been accompanied by the near-immediate release of all the significant relevant analysis and advice.

Nonetheless, and to their credit, the government is slowly getting there. There was a big proactive release a couple of weeks ago of all sorts of central government documents (mostly advice to ministers and Cabinet papers) – individually important or not – on the coronavirus situation from the start of the year until mid-April, and there is a promise of another batch presumbly sometime next month. What is done is now done, but the release of those papers – many of them written to very short deadlines and in the fog of war – helps us, as citizens and voters, assess the quality of the central government advice and decisionmaking process. And since Covid hasn’t gone away, it may even help clarify where improvements might be made – even demanded – in government contingency planning against the risks of further problems.

But, of course, there are other public sector agencies operating at arms-length from ministers, exercising a great deal of discretionary power (including through the Covid crisis), and not covered by the government’s own pro-active release. I’m thinking most notably of the Reserve Bank and, these day, the Monetary Policy Committee, a statutory body – members each appointed by the Minister of Finance – charged with the conduct of monetary policy.

Without any great optimism about a positive response, and fully expecting the request would simply be the first step on the path to an appeal to the Ombudsman I lodged an Official Information Act request on 20 April.

I am writing to request copies all papers prepared by or for staff or

management of the Reserve Bank for the Monetary Policy Committee in

2020.I am, of course, well aware of the Bank’s typically obstructive

approach to releasing such official information in normal times.

However, given the scale of the events the Committee has been

grappling with this year, the magnitude and unusual/unprecedented

nature of many of the interventions (and decisions on occasion not to

act), the scale of the economic and financial risks the wider public

and the taxpayers are being exposed to, there is a clear and strong

public interest in the release of these particular papers, without

necessarily creating a precedent for more-general release of MPC

papers. In addition, I would note that the succession of meetings

this year, and the fast-moving nature of events, means that papers

written even a month ago are already likely to have aged beyond the

point of immediate market sensitivity much more quickly than would

normally be the case.Public accountability demands much greater transparency.

“Typically obstructive approach” refers to the Bank’s adamant refusal to release any papers relating to monetary policy decisions, at least unless they are perhaps 10 years old (they did once release a set of those, and I haven’t tested whether the effective threshold is 3, 5, 7 or 10 years past).

“Public interest” is in reference to the provision of the Official Information Act which states that for many of the possible withholding grounds

Where this section applies, good reason for withholding official information exists, for the purpose of section 5, unless, in the circumstances of the particular case, the withholding of that information is outweighed by other considerations which render it desirable, in the public interest, to make that information available.

I had a reply on Thursday. In fairness, at least it was only a day or two beyond the 20 working day deadline, although I doubt it took the Bank any time at all to decide its response. The substance didn’t really surprise me at all, even if it was a disappointing reflection on the continued refusal of the Reserve Bank to accept that the principles of open government, the principles of the Official Information Act, apply to them and to the Monetary Policy Committee as well.

They pointed to the various press releases and Monetary Policy Statements (which, personally, I wouldn’t have thought were in scope, although that is beside the point) and went on

We are withholding all remaining information within scope of your request under the following grounds:

section 9 (2)(d) – in order to “avoid prejudice to the substantial economic interests of New Zealand.”

section 9 (2)(g)(i) – to “maintain the effective conduct of public affairs through the free and frank expression of opinions by…members of an organisation or officers and employees of [an] organisation in the course of their duty.”We have considered your views regarding the need for the information to be released including, the scale of the events the Monetary Policy Committee has been grappling with this year and potentially, strong public interest in the release of these particular papers.

The Reserve Bank is currently conducting monetary policy in an environment of great uncertainty and market volatility. In these circumstances it is especially important that the MPC has the space to assess all the available information, select monetary policy tools, convey clear messaging through its Monetary Policy Statements, and evaluate its actions as it proceeds. The release of such recent MPC papers would be likely to interfere with the effective implementation of monetary policy.

As you are aware the Reserve Bank has a statutory duty to make official information

available unless there is good reason for withholding it. In this instance the Reserve Bank believes that there is good reason for withholding the requested information and that the public interest in releasing it does not outweigh the reasons for withholding we have listed above.

Note that the request was not for every casual email staff and management might have loosely exchanged over the months, it was for the papers prepared for the Monetary Policy Committee, a statutory body that the Governor (who also sits on the Committee) and staff advise and service.

There is a close parallel to the way (a) government departments advise individual ministers, and (b) the way an individual Minister’s Cabinet paper seeks the approval of his/her colleagues. Advice and recommendations and analysis flow to decisionmakers, and decisionmakers decide. Sometimes that advice is poor, sometimes good, sometimes necessarily rushed, sometimes not. But to their credit, the government has released the significant bits of advice/recommendations – whether or not each of those pieces of advice make advisers or decisionmakers look good, whether or not decisionmakers accepted that advice or not, whether or not the advisers might now wish they’d advised something different?

What make the Reserve Bank – the Governor as chief executive, or the statutory MPC he chairs – think it should be exempt from that sort of scrutiny and transparency, through one of the most dramatic periods of modern times (including as regards monetary policy)?

One of the excuses the Bank has sometimes advanced for withholding monetary policy materials is that releasing them might give away information about future strategy. Even if that were true, it is really grounds for selective redaction, not broadbrush refusal, but at present it is a particularly absurd argument. For example, my request encompassed papers relevant to the February MPS – you’ll recall that that was the one in which they played down coronavirus and were rather optimistic about the rest of the year, adopting a very slight tightening bias. Whether or not those were reasonable views at the time, they were long since overtaken by events. Nothing in the advice and analysis provided to the MPC for that MPS has any possible bearing on actions the Bank or market is taking now.

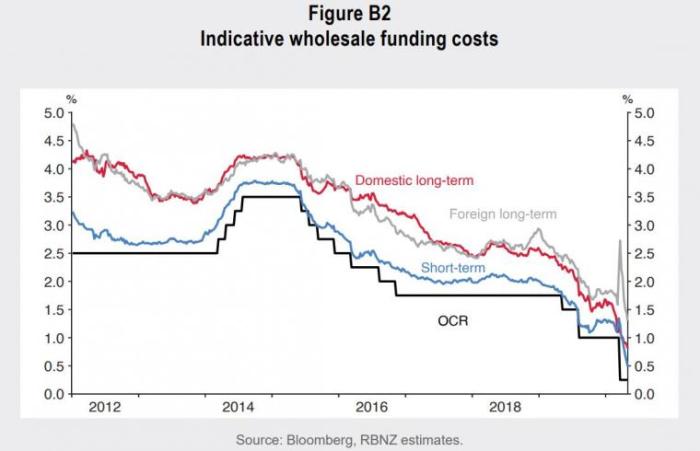

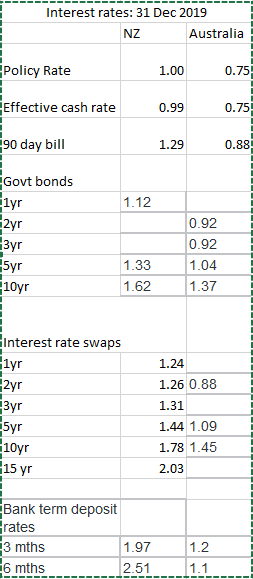

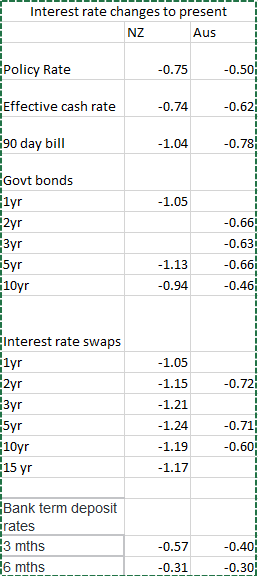

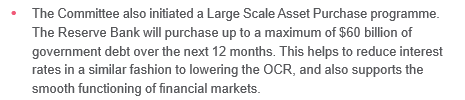

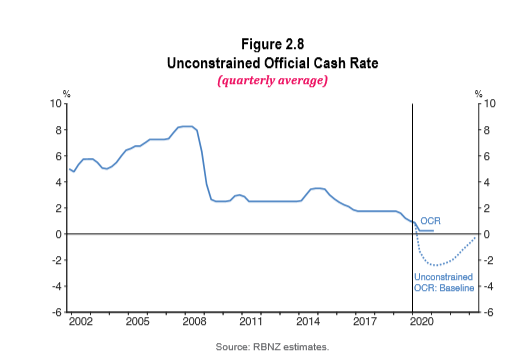

But take more recent events. The MPC issued, and has since reaffirmed, their pledge to not cut the OCR for a year. They provided no supporting argumentation or analysis for that stance, but presumably there must have been some analysis and advice, perhaps around these mysteroius “operational obstacles” that the Governor, as the MPC’s spokesman, keeps referring to.

Or the LSAP programme? Surely there must be staff analysis and advice, provided to MPC under the imprimatur of the Governor, on the likely effects of such a programme? What possible grounds can there be for simply refusing to release any of it (as distinct perhaps from withholding specific paragraphs touching on the implementation plans for example)?

All the excuses about

In these circumstances it is especially important that the MPC has the space to assess all the available information, select monetary policy tools, convey clear messaging through its Monetary Policy Statements, and evaluate its actions as it proceeds. The release of such recent MPC papers would be likely to interfere with the effective implementation of monetary policy.

could no doubt equally be argued by officials in Health and Treasury etc, or by Ministers. But to their credit, ministers have recognised the importance of openness and put the advice out there – rushed and perhaps inadequate, rapidly overtaken by events, as sometimes it inevitably was. And at least Ministers have to face the electorate in September, but the only effective accountability for the Governor and his MPC (many of whom refuse even to be interviewed) is the sort of openness and transparency that the OIA has long envisaged.

The Bank likes to claim that it is very transparent, but solely on its own terms and its own definitions. Transparency does not mean telling people what you want them to hear when you want them to hear it – everyone does that, in their own self-interest. Transparency is about the stuff you sometimes find uncomfortable, even embarrassing, or just very detailed, but which you put out anyway. Had she wanted to the Prime Minister could have run the sorts of excuses the Bank did – claiming that she held a press conference every day and ran full page adverts in newspapers every day telling people what she thought they needed to know then – but to her credit she is better than that, and recognised the very strong public interest in much greater transparency – some of which might put her or her officials in a good light, some not. It is what open government is about.

I’ll be referring this to the Ombudsman, and perhaps seeking from the Bank all material relevant to their consideration of this particular request, but if the government is serious about its commitment to openness and transparency, it is past time for the Minister of FInance to have a word with the Governor and with the others he himself appointed to the MPC, and with the chair of the Bank’s Board – whom he appointed – and strongly urge, come as close to insisting as he can, that extraordinary times, extraordinary monetary experiments, call for a much greater degree of openness that the Bank has, hitherto, been willing to display.

If The Treasury’s advice to the Minster of Finance on these matters is open to scrutiny in these exceptional fast-moving circumstances, why not the Reserve Bank’s advice to their decisionmaking body? As it happens, the Secretary to the Treasury is now a non-voting member of the MPC, so perhaps she might have a word with her colleagues and draw attention to what transparency and accountability are supposed to mean in New Zealand.