A commenter on a recent post left the reasonable question

if the RBNZ is flooding banks with deposits/reserves to pay for its QE, why are the banks still paying 2.5% to raise term deposits from the public ? Surely the banks have more cash than they know what to do with ?

Well might she ask. And her question prompted me to think a bit harder about useful steps that could be taken in response to what looks like quite a glaring anomaly. At present, the Reserve Bank pays 0.25 per cent on settlement balances banks hold at the Reserve Bank, banks are paying much the same rate on (wholesale) 90 day bank bills, but when I checked this morning the average retail rate on offer for a six month term from our five largest banks was about 2.15 per cent.

It wasn’t always so. Here is a chart showing the 90 day bank bill rate and the 6 month term deposit rate (the one the Reserve Bank provides a long time series for) back almost 30 years.

Short-term wholesale rates used to be a bit higher than comparable maturity retail rates. That made sense. The marketing and admin costs associated with one $20 million bank bill are going to be a lot lower than those associated with 400 retail deposits of $50000 each. The margin ebbed and flowed a bit, but it was rare for retail rates to be below wholesale. All that changed at the time of the 2008/09 recession and financial crisis, and the old relationships have never resumed.

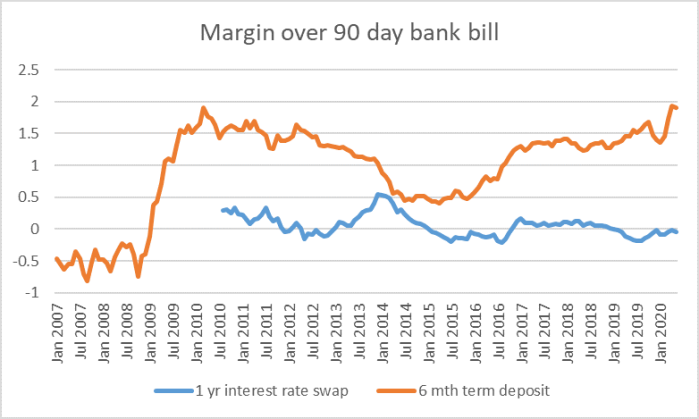

In this chart I’ve taken a shorter period – since the start of 2007 – and have also shown the rate on a 1 year interest rate swap (for which the Bank has only published data since mid 2010).

The maturities differ a bit, but despite that you can see how similar the two wholesale rates have mostly been and how different they’ve been to retail rates. And here, for the same period, are the margins between the 6 month retail rate and the 1 year swap rate respectively and the 90 day bank bill rate (itself usually moving very similarly to the OCR).

The gaps that sometimes open up for a while between the swap and bill rate just reflect the maturity differences – eg in 2013 and 2014 the Bank was strongly expected to raise the OCR so swaps yields rose in anticipation. Over time, the differences have been small and non-persistent. By contrast, the margin between retail and wholesale rates has typically been large and somewhat variable.

What accounts for this weird situation in which Michael Reddell private saver can get, pretty consistently, 150 basis points more for my smaller deposit than Michael Reddell trustee of the Reserve Bank staff pension scheme can get for the much larger amounts of money he (and other trustees) formally own (on behalf of the members)?

(Totally parenthetically, hasn’t policy been pushing people into collective savings vehicles – where they can only get the lower rates – ever since Kiwisaver was set up?)

It has a great deal to do with the 2008/09 crisis conditions, and perceptions and regulatory responses thereto. In New Zealand in the run-up to 2008/09 banks had had a very large share of their funding in the form of very short-term foreign wholesale instruments. That funding was cheap and easy to raise – times were good, money was easy, the mood was exuberant – and banks simply did not believe those markets could ever seize up (I’ve told the story previously of one very senior risk manager of one of the big banks who when we were doing pandemic planning in about 2006 asserted that very strongly). They did. More generally, wholesale runs were the catalyst for the failure of various major institutions abroad.

And so, perhaps understandably, there was a quite a reaction, by banks themselves (scares change behaviour, for a time at least), rating agencies, investors in bank debt, and regulators. In this post I will be focusing on the New Zealand regulatory intervention, but I don’t want to be read as suggesting it was the whole story (in fact, some readers may have memories long enough to recall my arguing 10 years ago that the regulatory effect then was probably small, relative to the private market response in those early post-crisis days).

Prior to 2008/09, the Reserve Bank had never had minimum liquidity requirements for banks. It was talked about from time to time – we used to worry, some more than others, about the macro risks associated with very high levels of short-term foreign debt – but in a small organisation it had never been a top priority, and there was Basle II to implement.

The Reserve Bank, The Treasury, and the banks got a fright in late 2008. It generally wasn’t totally impossible for our banks to borrow abroad but for a time it was very difficult to borrow (including on terms that didn’t send an atrocious signal) for much longer than overnight. Even with their prior fondness for fairly short-term debt, that was troubling for banks. (None of this, of course, was about the health of our banks or their parents; it was all about global markets seizing up.)

There were immediate policy responses to get through that episode – Reserve Bank liquidity provision, Crown guarantees for new wholesale borrowing – but also a fairly quick Reserve Bank policy response to try to reduce or substantiallly eliminate the risk of finding ourselves in that situation again. For a bank with a sound asset base, it is almost a given that a central bank will eventually lend if necessary, but the idea was to put buffers in place that meant we weren’t the port of first resort if things got tough, and (since banks’ board never like relying on central bank funding) to reduce the extent of pro-cyclical shocks to credit availability.

There are a number of strands to Reserve Bank liquidity policy but the bit I want to focus on is the one-year Core Funding Ratio (CFR) requirement: now that “core funding” must equal at least 75 per cent of each bank’s total loans and advances. In practice, as banks do with capital buffers, they typically hold a considerable margin above the regulatory minimum. Here are systemwide numbers since 2013, when the minimum ratio was raised to 75 per cent.

And what counts as “core funding”?

Well, here is the summary from the policy document

Simplifying a bit, core (Tier 1) capital counts, as does all funding with a residual maturity in excess of one year, half of any long-term securities in the period between six months and one year to maturity, and (per the table) “short-term non-market funding”.

There is quite a lot of other detail defining “market funding”, but suffice to say that long-term wholesale (market) funding is attractive for these purposes (sell a 7 year bond, and the bank can count it as core funding fully for six year, and half for six months), but so is money from the little person – you and me. Anything we hold, so long as it less in total than $5 million per bank, counts at 90 per cent as term funding, even if the relevant account is fully liquid and the deposit are withdrawable on demand without question. It isn’t just individuals; corporate cash holdings are treated the same (not on an instrument by instrument basis but based on the total holdings of that firms and all its related parties). And other financial institutions – even small and passive ones (like the Reserve Bank superannuation one) – are explicitly excluded.

It is just great if you are an individual depositor. But it is really rather anomalous, and not based on any terribly-robust analysis.

Now the missing bit in all this is the cost of that long-term wholesale funding, which is more or less as valuable as a retail term deposit for CFR purposes. It is hard for outsiders to get a reliable fix over time on those costs, but from time to time the Reserve Bank includes a chart like this in the MPS, as it did last week.

Quite how they put it together isn’t that clear (and the underlying data aren’t disclosed), but the line to focus on is really the grey one – the estimated all-in cost of long-term foreign funding (issuing the debt in foreign currency and hedging it back into NZD for the term of the loan). The margin between the grey line and the OCR is both large and variable. Much of that typically has to do with the hedging costs – again not something easy for outsiders to track routinely, but which have typically been more adverse, and more variable, over the last decade or so than was typically the case in the years prior to 2007. If the hedging costs were consistently low, the grey line would be a lot closer to the OCR and the cost of domestic wholesale short-term funding, which in turn would mean banks would price term deposits much closer to the OCR/bank bill or to those domestic interest rate swaps.

Perhaps the other relevant consideration here is that the New Zealand economy as a whole is still quite heavily dependent on foreign capital, and in particular on foreign debt intermediated through the banking system. If our net international investment position was different, there would be a larger stock of domestic retail/corporate deposits, and the relevance of the offshore funding costs (including hedging) might be a lot less.

But as it is, the banks are compelled to have – in total – a lot of funding from retail and long-term wholesale sources. A rational bank will price term deposits so that the cost of that form of core funding is typically and roughly equivalent to the cost of equivalently-useful long-term wholesale funding (the latter mostly from abroad).

When the CFR was put in place there was a recognition that core funding would be a bit more expensive that other funding, and that was a price judged worth paying. By the time of the increase in the minimum ratio to 75 per cent, this huge margin between the cost of “core funding” and the cost of other liabilities seems – from the relevant RIS – to have come to be accepted as some sort of new-normal, perhaps even desirable. At the time, the Bank even toyed with the idea of the CFR as a so-called macroprudential tool (it appears in the MOU on such things agreed in 2013), and there was a view afoot that a higher CFR might enable us to tighten overall conditions without pushing up the exchange rate.

But, frankly, it all looks a bit daft at present. The policy is premised on the notion not only that Michael Reddell as personal depositor is less likely to run on his bank than Michael Reddell the super fund trustee and that – even if granted that that was true – that stickiness (possibly not even rational, since I might just be slacker about my finances than about my fiduciary responsibilities) was so valuable from a financial stability perspective to be worth driving such a massive wedge between the rates available on two products with absolutely the same credit risk. More generally, if you were around in 2007/08 you may recall (a) the retail runs on domestic finance companies, and (b) Northern Rock and the queues down the streets in the UK. There probably is some value in encouraging banks to have a reasonable volume of longer-term funding, that can’t be encashed on demand by the holder, but there is little obvious basis for distinguishing deposits of the same maturity held by individuals, by companies, by other small financial institutions and so on. A cost-benefit analysis simply could not support the sorts of – inefficient – wedges we have come to see. I emphasis the “inefficient” because (a) the Governor likes now to refer to efficiency, and (b) more importantly, because the provisions of the Reserve Bank Act governing the exercise of prudential powers still do, as an important constraint on what the Bank does.

From a macroeconomic perspective, none of this much mattered when the Bank was freely able and willing to adjust the OCR as required, to more or less keep inflation towards target. If term deposit rates were going to be a little high, the OCR would be lowered, and although there would still be much the same wedge between retail and wholesale rates, the level of retail lending and borrowing rates could be more or less managed to what the Bank regarded as consistent with the inflation target.

These days, however, the Bank seems to regard itself as bound to an exceptionally rash commitment it made in a hurry on 16 March, not to reduce the OCR further. And the Governor and Deputy Governor are reduced to asking really really nicely (or not so) for the banks to lower lending rates, even as they say they can ‘rationalise’ – in terms of those funding costs – why they don’t. To me the answer is straightforward: if as a central bank you think retail rates need to be lower, consistent with your inflation target, then cut the OCR until retail rates get there. Simple as that.

But if the Governor really does regard himself as honour-bound – like some teenager’s promise to a dying parent that he’d never ever partake of the demon drink – there are still options, and ones that might make a real difference where it matters to depositors/borrowers. Specifically, the CFR.

For example, the Governor – and this is his decision, not the MPC’s – could lower the minimum CFR to, say, 65 per cent (and commit to keep it no higher than that for, say, the next five years). Do that and the pressure would come off term deposit rates very quickly and the relevance of those marginal foreign term funding costs would abate. He could do more complicated things as well – options we looked at a decade ago – of imposing a minimum requirement only on the share of foreign funding that is long-term (recognising that we don’t have largely repo-funded investment banks as they had in the US). I wouldn’t recommend the more complex changes in the short-term – action is what is called for, and not things that take lots of careful drafting and consultation.

You might – perhaps especially if you were a bank supervisor – think it strange to propose such a relaxation in the middle of a very troubled period. But bear in mind several points:

- we aren’t in the exuberant phase of the cycle (unlike, say, 2005 to 2007), where banks are just pursuing whatever is cheapest regardless of rollover risk,

- we’ve already got to the point where the Bank is happy to provide almost limitless funding to the banks. They are running term loan liquidity auctions, and for now getting no takers. And although the wholesale deposits that arise through the bond purchase are technically pretty short-term, I heard the Governor on the radio yesterday stating that he thought the Bank would be holding the bonds to maturity (in which case the funding will also be there for years). None of this funding counts as ‘core funding” for CFR purposes,

- there was no robust cost-benefit analysis of just what was being gained from the CFR, let alone the specific parameter settings (nothing even to match what was done for capital last year). In other words, the current 75 per cent is no less or more ad hoc than a 65 per cent ratio for a few years would be.

- the Bank has already wound back its capital requirements (delayed the start of the increase in required capital), so there would be no particular inconsistency in doing the same for liquidity, given the anomalous pricing the Bank’s rules are producing.

The Reserve Bank was a fairly early adopter of a core funding requirement after the last recession. Many other countries now have something called a net stable funding requirement as part of their bank supervision arrangements. The rules are a bit different, and no doubt each country has its own specific calibrations (and I’m not that familiar with the details of any of them). This post is not an argument for getting rid of a funding requirement rule – although in the end it is the quality of bank assets that matters mostly – but for recognising how large a wedge our specific rules have driven, and the way that now (with the self-imposed OCR floor) contributes to holding our retail lending rates up.

I’ve noted in a couple of posts, including yesterday’s, that even though the New Zealand and Australian policy rates are essentially the same, retail term deposit rates in Australia are much lower than those – offered by the same banking groups – in New Zealand (and by much more than any slight differences in credit quality might explain). As I noted earlier, it isn’t just regulatory provisions that explain the wedge between core and non-core funding of the same term and credit, but it seems likely that the specification of the NZ rules explains the bulk of the difference between New Zealand and Australian term deposit rates.

If the Governor is determined to stick to his crazy OCR promise for now, action on the CFR offers the fastest surest mechanism to materially lower domestic retail interest rates. The Governor says that is a priority for him. This decision is entirely his.

It is fair here to point out that the Governor’s prudential regulatory powers have to be used for prudential regulatory purposes – soundness and efficiency of the financial system – and can’t just be used as a monetary policy tool (any more than LVRs could). But on this occasion that should not act as a constraint: after all, that large wedge between returns on instruments of the same maturity and credit, dependent solely on who holds the instrument, doesn’t look good on any sort of efficiency test, and I’m sure I’ve heard in recent weeks the Governor suggest – quite credibly – that lower retail lending rates were likely to be, at the margin, a positive contribution to financial stability. When efficiency and soundness ends are both served it really should be an easy call. There is a Bank Financial Stability Report due next week, which would be a good opportunity to announce such a change – or for MPs and journalists to grill the Governor on why he would continue to oversee a policy that drives such a wedge into the interest rate structure.

UPDATE: Shows how many initiatives there have been that one can lose track of. A reader draws my attention to the fact that the Reserve Bank had already cut the CFR in late March. I must have read that at the time and then forgotten it. Will have to reflect further then on why term deposit rates are still so high relative to wholesale rates. One possibility might be uncertainty about how long the relief will last.

I think you answered my question in this bit of your commentary Michael viz And although the wholesale deposits that arise through the bond purchase are technically pretty short-term, I heard the Governor on the radio yesterday stating that he thought the Bank would be holding the bonds to maturity (in which case the funding will also be there for years). None of this funding counts as ‘core funding” for CFR purposes

So, even though banks have more cash than they know what to do with – and will have for a long time by the look of it – that funding doesn’t count for CFR purposes, meaning QE has made little difference to banks CFR activities (i.e. still plenty of competition for retail TDs)

I note your suggestion the CFR should be cut to, say, 65%, but wouldn’t another solution be to count some or all of the QE-induced wholesale deposits as CF (that is, if the Governor really believes many of the bonds purchased will be held to maturity)

Alison

LikeLike

Alison

Thanks for prompting me to write the post. Your alternative would be more complex than it sounds because banks don’t know which deposits arise from RB bond purchases, they only see the aggregate effect.

Another commenter has pointed out that the RB has already eased the CFR – in a release i now vaguely recall reading, but that partic point wasn’t in focus at the time

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/news/2020/03/mortgage-holiday-and-business-finance-support-schemes-to-cushion-covid-impacts

As they note, still then a puzzle why it hasn’t flowed thru to retail rates. One possible strand of an answer is uncertainty about how long relief will be provided for – if for only a few months banks would not want to risk losing TD mkt share. Will have to reflect a bit further.

LikeLike

ANZ bank have just dropped 1year fixed loan rates to 2.79%. Interest rates are already falling.

LikeLike

I always enjoy your analysis, though would note the RBNZ quietly reduced the CFR on 24th March to 50%. See link below, halfway down the page.

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/news/2020/03/mortgage-holiday-and-business-finance-support-schemes-to-cushion-covid-impacts

The question now is why is it not flowing through to retail rates?

LikeLike

Oops. I do now remember reading that at the time. Thanks for drawing it to my attention, and i have updated the post.

I wonder if the failure to specify any mimimum period for the relief might be relevant?

LikeLike

I’m a bit puzzled

Cutting TD rates will not induce people to spend

Depositors will see this as an income cut, and will hunker down even more

We are in a world where quite a lot of incentives are perverse

LikeLike

offsetting income and substitution effects at work re depositors, but they work in the same direction for borrowers. In this case, lower TD rates will help lower lending rates.

LikeLike

But interest rate sensitivities on the lending side will also be very muted, or in fact dominated by more fundamental considerations. Rates are already low enough that they are barely part of the equation for most decisionmaking. Lowering them slightly more will change very little.

LikeLike

Empirical question, but many SME lending rates are not very low at all. There was also the ECB research paper I linked to last week suggesting that even as rates moved negative corporates sitting on cash chose to engage in more real investment.

But I’m also interested in the distributional angle: in times like these real returns to depositors “should” be lower and burdens on variable rate borrowers “should “ be lower.

LikeLike

I don’t think those would be my starting points for a distributional analysis

But nor do I think that a distributional analysis would be easy. This crisis has dumped extremely unevenly from those who have benefited to those who have been devastated. Interest rates are mostly a trivial part of those disparities.

LikeLike

Yes, interest rates are often small – compared say to job loss or devastation of a business – but 5% pa on a $500000 Akld mortgage isn’t trivial either.

In general my take would be that the sort of people with lots of deposits haven’t typically been worst affected (typically older, often out of the labour force, and actually the demographic the lockdown was primarily protecting).

But I would rate the macro arguments higher , incl the potential for significant exch rate adjustment if we chose to materially lower the OCR.

LikeLike

We are an SMB with good equity and are still paying 9% on OD, many SME’s are paying more than that. Still room to cut rates.

LikeLike

Yes, in this sort of economic climate, with deflationary risks to the fore, the OCR should probably be -5% and your OD rate perhaps 4%

LikeLike

LOL, negative 5%???

Right…….You realise this will never happen right? It’s looney tunes Michael, let alone totally unproven bordering on unethical. Even Jerome Powell is extremely reluctant to go negative because they know the message that sends to Main St and the Markets is essentially “game over” .

There is no bank without depositors and i sure as hell will be pulling every cent I have in any bank long before zero OCR. I myself luckily have a wide asset portfolio and a zero debt business to full back on.

Alastair & Co don’t need to see a negative OCR to assist his SMB. He needs banks to just play fair. Post Covid19 they must be forced to incentivise actual business loans OVER the private mortgage asset bubble funding model. That failed myopic model assisted by “too lower interest rates for far too long” in the first place going right back to post 9/11 is why we are where we are. Central Bank economists have a great deal to answer for..

RBNZ & Government should not be asking banks (begging almost)…they should be mandating.

LikeLike

Actually I think deeply negative real interest rates probably will happen at some point. But time will tell.

The Governor of the Bank of England was this week moving closer to the possibility of negative rates.

Of course ideally the economy would rebound strongly and v low interest rates wouldn’t be needed for long.

LikeLike