I had a long chat yesterday to a reader who’d read a forward-looking piece I’d written recently and was concerned that in the halls of power there might be insufficient appreciation of just how serious the economic situation is. My caller was just about to lay off a fairly large chunk of the staff in his company.

I was inclined to share his view – although it is hard to know what ministers/officials really think, as distinct from the official happy-talk – and have been uneasy that, for example, official forecasts of the unemployment rate getting to, perhaps 7 or 9 per cent were giving some a sense that really things weren’t so bad, and that more or less enough was being done at a policy level. After all, actual headline unemployment rates are much higher in some other countries (US and Canada), and the unemployment rate here was higher than those forecasts back in 1991/92. Just this morning on RNZ, the Governor of the Reserve Bank seemed to be suggesting that everything was in hand, and not much more needed to be done by policymakers as a whole.

I went straight from that call to a Zoom seminar put on by the Law and Economics Association on economic policy responses to Covid-19. There were three economists speaking, none of whom I would usually associate with calls for a more active and interventionist state – Eric Crampton (New Zealand Initiative), Andreas Heuser (Castalia consultants, and formerly Treasury), and Richard Meade (of Cognitus, also consultants). The slides for all three presentations are here (and I think they said they are planning to put the video up as well). None seemed remotely comfortable with the current situation or content that what needed to be done had been done.

I found it interesting that all three were advocating more-liberal state-sponsored/provided access to interest-free credit.

Heuser’s focus was on business credit, noting the risks (of widespread insolvency) that our more onerous lockdown (relative to Australia) had created and the lack of success of the government’s business loan guarantee scheme (and that the new interest-free scheme is available but offers meaningful amounts only for quite small businesses). He seemed to be arguing for more generous bank-administered schemes (in which, for example, any government credit is more directly subordinated).

Eric Crampton’s focus was mostly on other aspects, but he repeated his enthusiasm for the scheme the Initiative was proposing a couple of months ago, allowing individuals to borrow from the state quite readily. Repayments would then be made over many years through the tax system – akin to the way student loan repayments are done – with borrowings to be interest-free up to a reasonable threshold (linked to your past taxable income) and carrying an interest rate for amounts beyond that.

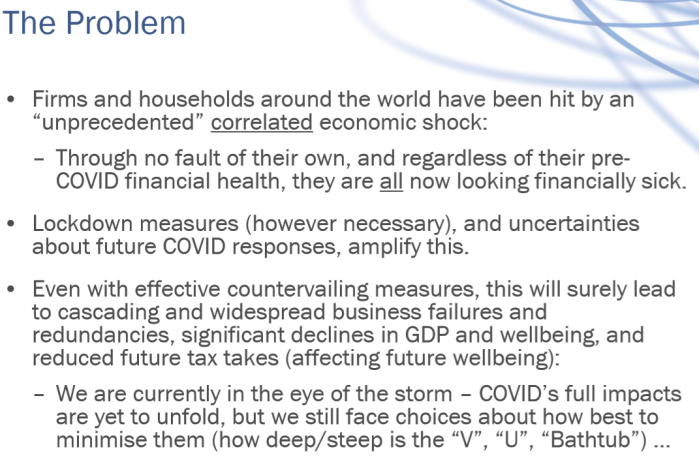

My main interest, though, was in Meade’s proposal, which has apparently been around for a while but which I’d not noticed previously. He starkly puts the problem this way

And goes on to note that both firms and households rely on each other, and (in the large) none could really be confident of their own viability if they cannot be confident of the other’s. He argues that the numerous support measures rolled out since mid-March have been too scatter-gun and selective to provide any widespread confidence or (thus) willingness to spend. And they do this, on his telling, even as they rack up a huge fiscal costs, which will be paid (directly, or through foregone options) by generations to come.

His proposal has these features.

(Note that his second line means big businesses and existing beneficiaries/public servants would not be eligible.)

As Meade notes, in an ideal world, such a framework would have been put in place three months ago, so that as we headed into the worsening Covid downturn everyone would have had much greater clarity about the buffers that would be in place. But not having done so then does not mean, so he argues, that it should not be adopted now.

It is an interesting proposal, and among its features Meade sees these

Importantly, they replace government-imposed qualifying criteria and favoured cost lines with “self-selection criteria” and “self-prioritised cost lines”:

– They are “incentive compatible” in that taking out loans is a choice to personally pay higher taxes, which protects against over-borrowing (likely a lesser evil anyway);

– They otherwise rely on households using their private information to determine how much “income insurance” they need to remain able to pay their priority bills, keep their house(etc), and obviate the need for bluntly targeted subsidies.

Relative to the status quo, what Meade is proposing has some appeal, especially around certainty. If you can’t know what the wider economic environment will look like, at least you can have a sense of what buffers you might have available, and those your customers might have available to them.

But I don’t see what Meade is proposing as viable, in least in the way he proposes (as a substitute for really big additional fiscal outlays).

The first reason is that while he presents it as “ex post income insurance”, it is really nothing of the sort. When you buy income insurance – whether privately or through ACC – you pay your premium along with everyone else and hope you never collect on the policy. If you do have to collect on the policy, the cost is covered a little by your previous premia, but mostly by the premia of the people who will never claim.

By contrast, Meade’s suggestion isn’t income insurance, but simply “liquidity insurance” – as he notes, anti-slavery laws mean you can’t generally borrow secured on your future income, but Meade’s scheme ensures you can borrow if your income takes a sharp hit (his concern here is mostly for people for whom the welfare system provides a very low income replacement rate). But you, and only you, will pay every cent of the amount you borrow – secured, through the tax system, secured against your estate, so really only written off in extremis.

And he wouldn’t even make it available to big companies, even though big companies employ lots of people, make lots of investment choices etc etc.

And although his aim is to support confidence and demand – by giving everyone a sense that everyone else has access to liquidity and, thus, spending power – I don’t think it would have done that very effectively (even relative to the policies the government has adopted), particularly note for households. Lots of people – having just lost their job, or fearing doing so – would be very very reluctant to take on lots of new debt in the middle of a crisis, and instead would choose to cut their spending to the bone – precisely what Meade hoped to avoid. For small and (particularly) medium businesses, what Meade proposes is better than what we have, but still suffers from the weakness that (a) many firms probably won’t be coming back, and there is no particular public interest in them doing so (one motel in Rotorua is much the same as another, and so on) and (b) many businesses simply will not support more debt.

And the political system would just not be willing to stand by and say “well, you are on your own – you had the option to borrow and chose not to do so”. It would intervene with grants as well (as it has done, is doing). That is actually more like (although still not close to) what a risk-pooling insurance scheme looks like – those of us lucky enough not to lose our jobs help fund the support for those who did lose theirs (in, as Meade puts it, an “unprecedented correlated shock” where people find themselves in deep strife (again in his words) “through no fault of their own”. (I could also note that many households – any with significant equity in their house – have significant borrowing capacity anyway, without a new scheme).

I wrote about Meade’s scheme for two reasons.

The first is that I was struck by the fact that all three speakers at yesterday’s seminar favoured interest-free loans, including to businesses. Meade’s was the most developed model presented, and encompassed both households and businesses. The government seems to agree that zero interest is about the right rate at present – that is the rate it is lending at to those SMEs borrowing under its latest facility, and these won’t be the safest conceivable borrowers around. So these market-oriented – perhaps even “right-wing” – economists reckon zero interest makes sense at present, and the centre-left Minister of Finance seems to think so too (his revealed preference). The one person who doesn’t, of course, is the Governor of the Reserve Bank, who was heard on RNZ this morning saying that retail rates were “about right at present”. We all have a pretty good idea of where mortgage rates are at present – nowhere near zero – but check out interest.co.nz’s table of the multiplicity of business lending rates. We are in weird position where, faced with a huge deflationary adverse shock, the central bank’s Monetary Policy Committee is holding interest rates, for existing and new customers, well above where they should be.

The second reason for highlighting Meade’s scheme is that it gives me an opportunity to champion again my own proposal, first outlined in mid-March, which was designed to achieve quite a lot of what Meade was looking for. That was the proposal that the Crown would guarantee 80 per cent of last year’s net income for 2020/21, for individuals and for firms. Unlike Meade’s scheme, it would be quite costly to the Crown – although I believe no more costly than the scattergun approach currently being rolled out will end up costing – but it also offers genuine insurance, in which over time all chip in to cover some of the losses of those who were most severely adversely affected.

The most recent write-up of that proposal was in this post. That was a while ago now. I still reckon the basic framework remains the best option for conceptualising assistance (I saw other assistance as, in effect, credits that would be netted off against the “income insurance entitlement”).

In the spirit of ACC, if I were devising the scheme from scratch now, I might consider capping the payout at 80 per cent of individual incomes of up to $150000, with no compensation for losses on the income above that threshold. I might also consider guaranteeing not 80 per cent of last year’s net income for companies, but guaranteeing company net income at zero (or last year’s reported loss) – in other words, insuring that hitherto profitable companies did not go deeply negative, while recognising that profit variability is a much more natural phenomenon – every business every year – than labour income extreme variability. Each of those refinements would save money, but they would also complexify the system in ways that would have to be carefully considered if any government were to think the broad approach had merit. The broadbrush simplicity and certainty of the scheme – not playing favourites, not distinguishing large and small, simply buying time and providing some certainty – was the appeal of the scheme.

Of course, many of these schemes – and the government’s own interventions – are focused on the immediate situation, stabilising things in the short-term. But a year from now it is most unlikely that the economy – ours, or those in other advanced countries – will be anything like right again. There won’t be huge new fiscal capacity – not because of technical limits, or market constraints, but the realities of public tolerance – and that is where monetary policy should be doing its job. Much lower interest rates now aren’t mostly about boosting demand/activity now (the lags are simply longer than that) but about putting in place the right price signals – cost of domestic credit, returns to domestic depositors, and (perhaps most importantly) the exchange rate – that will support bringing private demand forward, and drawing private demand towards New Zealand producers, to get as back to full employment just as quickly as possible.