I’m not much into the notion of “economic plans” – all too redolent of Communist states, known mostly for their consistently underwhelming economic performance. But at least most of those old “plans” purported only to be five-year plans. By contrast, earlier this week the current New Zealand government – with one year left of its three year term – released a 30-year “Economic Plan”. It was released under the signatures of Grant Robertson, Minister of Finance, who has shown no sign of understanding or caring much about New Zealand’s economic challenges, and Phil Twyford, now Minister for Economic Development, but best known for Kiwibuild.

I guess the government must have known there wasn’t much there. It was, after all, released – to little fanfare – while the media were all concentrating on the Prime Minister’s progess in New York.

It is sold this way

The Government’s Economic Plan is set in the context of our wellbeing agenda and is designed to build a more productive, sustainable and inclusive economy to improve the wellbeing and living standards of all New Zealanders.

All lines and words we’ve heard endlessly now for two years. The introduction goes on

The Plan identifies eight key shifts and policy action related to each shift that will tackle the long-term challenges the New Zealand economy is facing. They signal our goal to balance outcomes across financial, human, natural and social capital, and will act as an overarching guide for government departments designing economic policy [er…don’t elected government’s set economic policy, not government departments?]

These shifts and initiatives will deliver on the four economic priorities in Our Plan: to grow and share New Zealand’s prosperity, support thriving and sustainable regions, transition to a clean, green and carbon neutral New Zealand and deliver responsible governance with a broader measure of success.

New Zealand has a unique opportunity to build on our strengths, and use these to lead the world on standing up to the economic challenges of the next 30 years, turning issues like climate change and the technological revolution into economic opportunities.

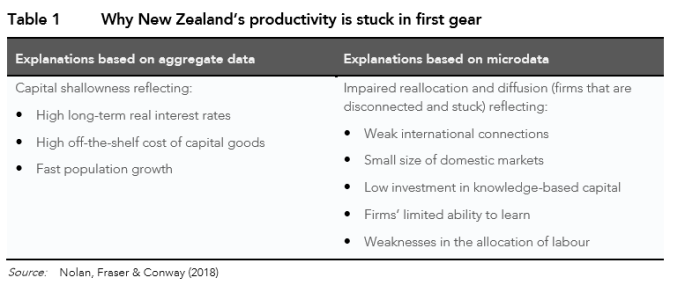

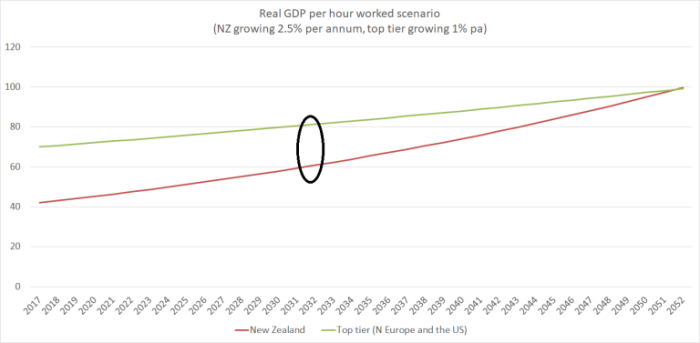

You might have thought that a good place to start would be recognising that we’ve trailed the advanced world for 70 years now, lagging behind on the productivity growth that underpins material standards of living and many other choices, rather than making idle and empty claims about “leading the world” in the next thirty.

Instead, there is the same complacency with which Labour went into the last election

New Zealand is recognised as being one of the best places in the world to live. Wellbeing is high for New Zealanders overall, but the benefits of economic growth have been unevenly distributed.

Nothing wrong with the growth performance really; just a matter of sharing the cake differently.

In fact, they sort of know that isn’t true. Get 10 pages into a glossy 30 page document and you do finally find this

Our productivity challenge is complex and long-standing.

But with no sign that they have any narrative explaining how we found ourselves in this position, or how the grab-bag of initiatives (there were 76 on one table – including Kiwibuild) they list might make a sustained and significant difference. (All governments for decades having had long lists – the previous government’s Business Growth Agenda as only the most recent, ineffectual, example.)

In fact, top of the list of their proposed ways to see economywide productivity lift are yet more plans

Industry Transformation Plans – adding value to key sectors of our economy and leveraging new opportunities.

Substance-lite.

The standard cliches are trotted out among the glossy photos

New Zealand is a trading nation and we want all New Zealanders to benefit from trade. We are building stronger international connections so that Kiwi businesses get greater access to markets around the world – not just for goods, services and investments, but also for people and ideas. At the same time, we are supporting businesses to get the most from trade and grow the value and reach of our exports.

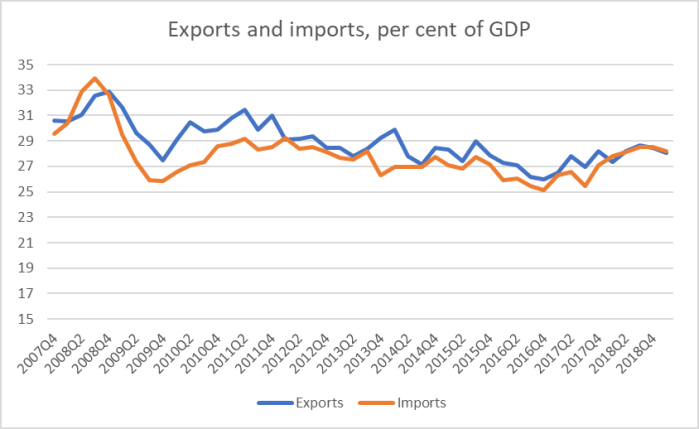

And yet, foreign trade (exports and imports) as a share of GDP is less now than it was at the start of the century, but there is no hint that the government (or its advisers) understand why. No mention of the real exchange rate in the entire document.

And it sort of goes downhill from there. Predictably, corporate welfare – aka the Provincial Growth Fund – tops the list of things that are going to make a favourable long-term difference to regional economies. The top two initiatives that are supposed to “enable a step change for Maori and Pacific economies” (whatever they are) are

Te Arawhiti – Office for Māori Crown Relations – fostering strong, ongoing and effective relationships with Māori across Government.

Government procurement – working to provide opportunities for Māori and Pacific New Zealand businesses to access contracts from the $41 billion we spend each year in Government procurement.

Both might be sensible steps in their own rights, but they simply aren’t commensurate with the challenge.

And there are old, and still silly, lines

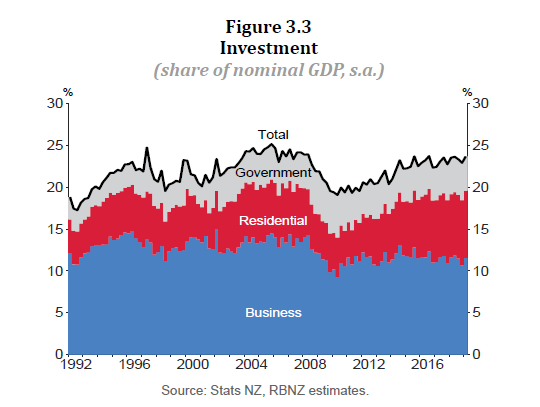

We know that New Zealand’s high house prices have diverted capital into the housing market and away from more productive uses. We need to redirect this capital to help businesses to innovate, invest in new technology and pursue growth opportunities.

I’m not sure how many times one needs to point it out but, given the the population, isn’t the conventional understanding that too few houses have been built, not too many? More real resources – on the government’s own original plans (Kiwibuild anyone?) – were supposed to be encouraged towards house-building. And not a mention of actually getting house prices down again.

In fairness, one might acknowledge that the first item on their housing/productivity page sounds okay

Urban Growth Agenda and RMA reform – working to get our urban markets working so they can respond to growth, improve urban land affordability, and support thriving communities.

The problem is that it sounded good two or three years ago, buried deep in the Labour Party manifesto, and it still does. But there has been almost no action so far, and no indication in market prices (eg of urban land) to suggest anyone much believes the government will act in ways that make a meaningful difference.

And it all ends with three pages of alternative “wellbeing indicators”, continuing to distract attention away from the decades-long failure on productivity.

There just isn’t much there. And nothing at all, for example, about the inevitable tensions (between, say, zero carbon goals and vague aspirations – and that is all they are – to higher sustained productivity growth). But, as ever, MBIE does well with the glossy heartwarming photos (from the family playing cricket on the beach at Sumner onwards).

But the Prime Minister must have wanted to suggest there was something there. The Herald managed to secure an op-ed from her about the plan, as part of their “Mood of the Boardroom” publication. Perhaps she didn’t choose the title but it (“My hope: a rising tide that will lift all boats”) didn’t suggest much agency, or hence much responsibility and accountability.

It was pretty vacuous piece, but as ever with her you get the sense that (a) she is more interested in sharing the pie that creating a climate conducive to rapid growth in the size of the (per capita) pie, and (b) that she has only a very limited understanding of the economic issues. That mightn’t matter much if she had a strong team of senior ministers who did. But there is little or no evidence of that.

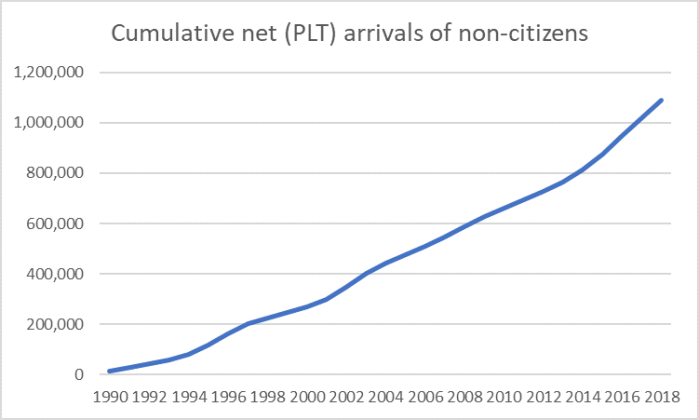

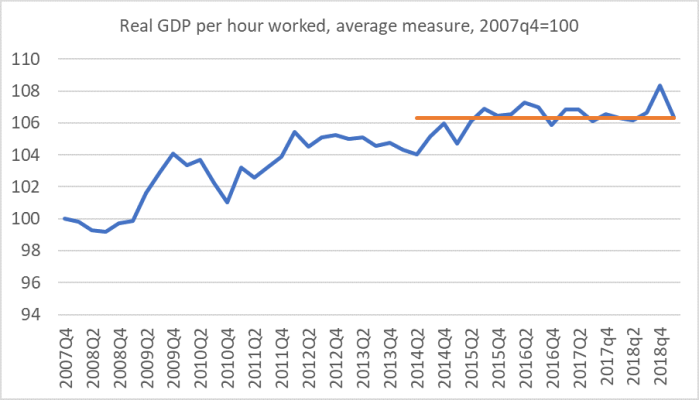

A good chunk of the article was devoted to make-believe stuff about just how well the economy is doing at present. Perhaps, knowing no better, she takes lessons from the creativity around the facts on display from the Governor of the Reserve Bank? She seems unaware that growth has been slowing (from never particularly fast rates), that leading indicators are poor, that productivity growth is almost non-existent, and she continues to parrot lines about how good our growth rates by international standards in ways that simply take no account of the rapid population growth rates here (just this week revealed by SNZ to have been even faster than they previously estimated). For someone focused on “wellbeing”, you might suppose that recognising that per capita GDP growth counts a lot more than the headline number would be a good first step. But I guess not.

The underwhelming text continues

We need to invest in infrastructure, because it’s the springboard for future growth. This Government is investing record amounts in hospital and school building programmes, alongside large investments in transport safety, regional roads and public transport

Perhaps you will agree with her on the first sentence (although it is striking how few of the touted projects seem to pass robust cost-benefit assessments), but whatever the merits of building more hospitals and schools those aren’t the sorts of infrastructures likely to make much difference to our woeful productivity performance (there might be other good reasons for such spending). Same goes for spending on “transport safety” – it isn’t exactly decongesting bottlenecks is it? And if you went for congestion pricing, existing infrastructures could be used much more efficiently.

And so it goes on. What about housing?

We’ll also keep tackling the long-term challenge in housing. Our economy works for everyone only when everyone has a warm, dry home, and a decent standard of living.

Well, no. A strongly-performing economy helps ensure/enable widely-spread decent standards of living. And her policy solutions are all about symptoms not causes

That’s why we’ve stopped the state house sell-off, stopped offshore speculators from driving up house prices, and built over 2000 state houses in the last year.

and

Business leaders agree that growth in New Zealand has been predicated too much on capital returns, and not enough on productive investment. To build an economy that works for all of us, we need to focus on productivity and innovation, especially through small businesses.

“Capital returns” sound like good things – good business make money for their owners – but I’m guessing she was trying to suggest something about capital gains on property. Except that no serious economic analysis really supports that sort of story – consumption as a share of GDP, for example, not having changed much for decades. And where she gets the bit about small businesses being particularly important, goodness only knows. I suppose it sounded good.

The vacuity goes on, limited only by the length of the column. She talks about how “we’ve always been an exporting economy” and having an “ambitious trade policy” but seems to have no idea that exports/imports as a share of GDP are (a) shrinking, and (b) small for a country our size, and somehow thinks that reforming the polytech sector is going to revitalise our services exports. Well, maybe…..

I don’t suppose Prime Ministers write this sort of nonsense themselves, but capable governments, really interested in reversing the decades of underperformance, would have a lot more substance to put in the mouths of their leaders. And capable leaders, with a serious understanding of the issues and imperatives, would simply demand much better.

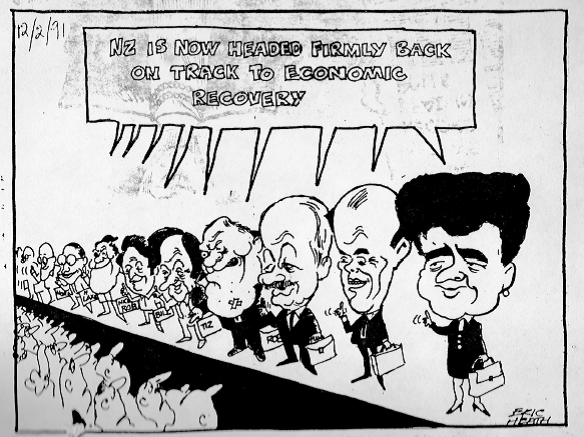

I’ve shown this old cartoon before.

It ran a generation ago now.

For some years, I had it pinned to the wall in my office – the sad procession of successive Ministers of Finance who for decades (this cartoon implies back to the 1950s) had promised that New Zealand’s decline would be reversed (made worse in this case in that Ruth Richardson must have said something along these lines in February 1991, just as the severe recession of that year was taking hold). Since then, we’ve had Bill Birch, Winston Peters, Bill English, Michael Cullen, and Bill English again, and although we’ve had plenty of cyclical ups and downs, never at any time have we looked like successfully or sustainably reversing our relative economic decline. It saddens me every time I look at this cartoon – so many decades, so much failure.

And nothing about Jacinda Ardern or Grant Robertson suggests we’ll manage any better if their policies were adopted than we have for the last 30 or 60 years.