Yesterday I wrote that

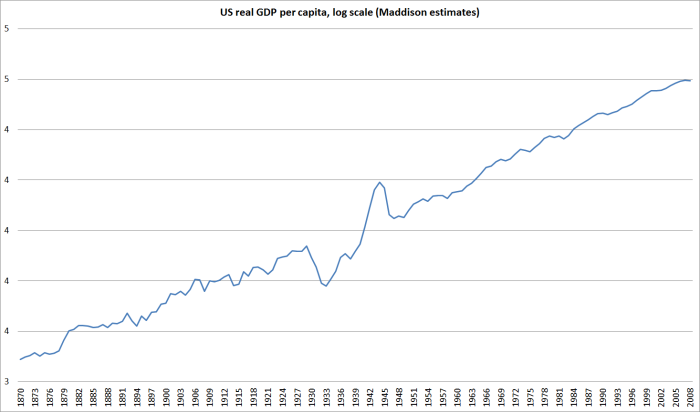

the single economic issue that I care about most is reversing the decline in New Zealand’s relative economic performance that has been going on, in fits and starts, since at least the middle of the twentieth century, if not longer.

A few minutes after posting that I noticed a story about some new work by Arthur Grimes and Sean Hyland of Motu, in which they suggest that perhaps there isn’t a problem at all. One of the authors was also nice enough to get in touch and alert me to it. As they put it

“…New Zealand households have amongst the highest material living standards in the world”

They have quite a long technical working paper, which I have dipped into to answer some specific questions but have not read in full. But the seven page Motu Note, “The Material Wellbeing of New Zealand Households” tells, and illustrates, the story in a very accessible way. It also covers some consumption inequality results which I’m not going to touch on here at all.

Grimes and Hyland attempt to develop a measure of material wellbeing, using as their basis the durable goods held by households that have a fifteen year old in them.

This framework is applied to household level data from the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) surveys, which include questions regarding the presence of household durables in the 15-year-old respondents’ homes, covering 16 consumer goods which range from the inexpensive (books), to expensive consumer durables (cars), whiteware (a dishwasher), utilities (an internet connection), and housing characteristics (the number of bedrooms and bathrooms in the house). This allows us to construct a dataset of household possessions for almost 800,000 households, covering 40 countries in the years 2000, 2009 and 2012.

And here is the picture with the headline-grabbing results. Having had below-average growth for the previous 12 years, these New Zealand households had, on this measure, material living standards in 2012 higher than the PISA-15 year olds households in all the other countries, except Canada and the United States.

I found the exercise (which has been funded by a Marsden Fund grant) an interesting one, and yet I wasn’t really convinced. Here are some of the reasons:

- How confident are the authors that PISA sample schools have been selected on the same basis in each country they look at? PISA isn’t mainly designed to generate wellbeing measures, and any differences there will immediately flow into these durable consumption results. I have read stories previously of strategic national selection of PISA sample schools

- The general thrust of recent literature has been towards measuring some concept of wellbeing broader than GDP (or GNI, or – better still – NNI, the gross income of New Zealanders, less depreciation). It wasn’t clear to me why this particular subset of types of households, and types of consumption, should be thought superior to even traditional measures of consumption.

- It wasn’t clear to me why durables consumption should be considered particularly important (except perhaps that the data are available in this sample).

- Since the authors only look at the possession of these durables, not at the cost of them, they don’t factor in how much the cost of these items might squeeze out other consumption. As a simple example, Amazon books are much more expensive here than in the United States (on account of transport costs). We have a lot of them in our house, and less of other stuff than we otherwise would.

- Perhaps these results might be relevant to child poverty debates, but we are typically more interested in how a country’s economy supports the consumption of all types of households within it.

- Since the birth rate in, say, New Zealand, is much higher than that in, say, Italy, a typical Italian household with a 15 year old probably has 0-1 sibling, while a New Zealand household has 1-2. In what sense are the consumption results then comparable?

- And what about the many other consumption items. For example, clothes, or restaurant meals, or foreign holidays (the latter more costly here than in, say, Belgium). Perhaps access to beaches and mountains is a plus here, but access to good newspapers, and great museums and art galleries certainly weighs in favour of people of most of these countries over New Zealand. And what of health or education spending – actual individual consumption, but often provided by the state?

- While it is reasonable to prioritise consumption over production, we know that savings rate vary quite widely across advanced economies. Today’s savings support tomorrow’s consumption. GNI (or NNI) measures provide a better sense of the consumption possibilities an economy generates than a particular subset of current consumption.

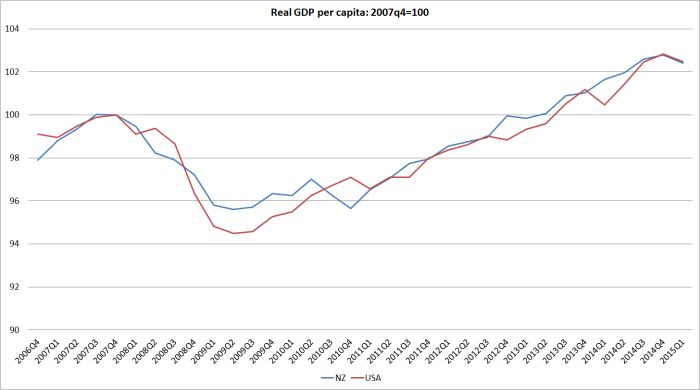

In wrapping up this post, I’m going to leave you with two charts.

The first is from the 2011 World Bank International Comparisons Programme. They have developed a measure of actual individual consumption, across almost all countries, at purchasing power parity values (ie adjusting for the differences in what things cost across countries). Here are the per capita results for the subset of OECD-Eurostat countries (a slightly larger group than Grimes and Hyland use).

Of these 46 countries, New Zealanders’ average consumption – across types of people – falls squarely in the middle of the pack, well behind most of the older OECD countries. Our ranking here looks quite similar to the rankings people are familiar with from GDP per capita, or even NNI per capita, charts. It isn’t a perfect measure, but it is much more comprehensive that the Grimes-Hyland one, and it isn’t obvious why it is misleading us about the material aspects of life in New Zealand relative to other advanced countries.

The final chart is just relevant to the New Zealand vs Australia comparison. On the Grimes-Hyland measure we score very similarly to Australia. Frankly that seems implausible as a representation of relative material living standards. Why? Because for fifty years large numbers of New Zealanders (net) have been leaving New Zealand, overwhelmingly for Australia. Very few Australians have come the other way. There is quite a lot of cyclicality in the flow, but the trend is very clearly in one direction only.

It wasn’t that way when more traditional GDP per capita estimates suggested that New Zealand and Australian economies were level-pegging. I entirely agree with authors who say that GDP per capita (or even NNI per capita) are not the be-all and end-all. People don’t change countries based on national accounts aggregates, or other international agency wellbeing measures. They are presumably changing countries because they believe the new country offers sufficient better material living standards, for them or their children, to offset the loss of the intangibles of home, extended family, and a culture and institutions one knows. The choices people make reveal their preferences, and it is unlikely that over decades they’ve got it systematically wrong (after all, they could have come home again, as many did). None of us knows how much poorer material living standards are here than in Australia, but we can be pretty confident they are now, and have been for some decades, worse.

(Real researchers can stop reading here, but..) I helped the 2025 Taskforce put together their first report, on closing the gap with Australia. The report focused on policy, and as the primary underpinning for the analysis used national accounts measures, but at their request I put together this – purely illustrative – box. I stress the words “purely illustrative”- it was a matter of what I could find quickly. It isn’t comprehensive, but – as the box concludes – that is why we have, and try to improve, national income and expenditure accounts.

Box 1: What do Australians get with their higher incomes?

Digging down to look at what people in the two countries actually consume can give a more tangible sense of the differences between New Zealand and Australian material living standards. Again, what is important in different climates varies, and tastes differ. But comparing living standards in New Zealand and Australia is easier than in most pairs of countries because the tastes and expectations are broadly similar.

These data are sometimes less reliable than the national accounts. Sometimes they are not compiled by national statistical agencies but by industry bodies. Even when statistical agencies are involved, things aren’t always measured exactly the same way in different countries. There is no single decisive fact. This box simply illustrates that across a very wide range of things that different people value or like to consume, the typical New Zealander has less than the typical Australian. Starting with where we live: the average size of a new Australian house or apartment built in 2007 was 212 square metres. In New Zealand, the comparable average was 193 square metres. Or what we drive: Australians have 619 cars per 1000 people, while New Zealanders have 560.

New Zealanders work more to earn our lower incomes: 887 hours a year are worked per head of population, as compared with 864 hours per head in Australia. Australians live longer: 81.1 years, compared with 80.2 years in New Zealand. Fewer people in Australia (111 per 100,000 people) die of heart disease each year than do in

New Zealand (127 per 100,000 people). Many fewer people die on the roads there: 7.8 each year per 100,000 people in Australia, 10.1 each year in New Zealand. Australians have more televisions (505 per 1000 people) than New Zealanders do (477 per 1000 people). And there are more broadband subscribers (10.3 per 100 people, compared with 8.1 per 100 in New Zealand).

There are more cinemas per million people in Australia (92.4) than in New Zealand (82.2). And more mobile phones too (906 per thousand people versus New Zealand’s 861 per thousand). Australians drink more than New Zealanders: both alcohol (9.8 litres per capita versus 8.9 litres) and fruit juice (34.4 litres per capita versus 24.8).

This isn’t comprehensive by any means – that is why we have national income accounts. And there are some measures on which New Zealanders have more than Australians. Australia has 34.9 McDonalds outlets per million people, but New Zealand has 36.9 per million.