I don’t really want to revisit the questions of whether retired politicians and senior public servants should be given honours largely for just turning up and doing a (fairly reasonably remunerated) job, or even whether there are really 15 people per annum in this country deserving of knighthoods. I touched on those issues in a post in January.

But two awards in yesterday’s list caught my eye. The first was the knighthood to former Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Bill English, and in particular the descriptions of Bill English’s contribution.

There was the official citation, the words put out under the name of the Governor-General, but presumably supplied by the current Prime Minister and her department

As Finance Minister from 2008 until 2016, Mr English oversaw one of the fastest-growing economies in the developed world, steering New Zealand through the Global Financial Crisis and the Christchurch earthquakes and ensuring the Crown accounts were in a strong financial position.

And, even more incredibly, a story by Stuff political reporter Stacey Kirk in which she noted that the official citation had been expressed “rather dryly”, as if it didn’t do full justice to the man’s contribution, and going on to observe, without a trace of critical scepticism or irony,

More colourful commentary at the time would globally brand him the man responsible for New Zealand’s “Rockstar Economy” – the envy of government’s worldwide and a textbook example of how to pull a country out of recession.

From a sudden jump yesterday in the number of readers for an old post of mine from 2015 on the emptiness – or worse – of the “rockstar economy” claims, it seemed that at least a few others might have been a bit sceptical of Kirk’s column.

I’m not going to quibble about everything. The Crown accounts were in a strong position when National took office in 2008, and were in a fairly strong position when they left office. Net debt was higher when they left office than when they took office, but the deficits which were emerging in 2008 as the recession took hold – recall that only a few months earlier in the 2008 Budget, Treasury’s best estimate was that the budget was still in (modest) surplus – were gone and the budget was back in surplus when National left office.

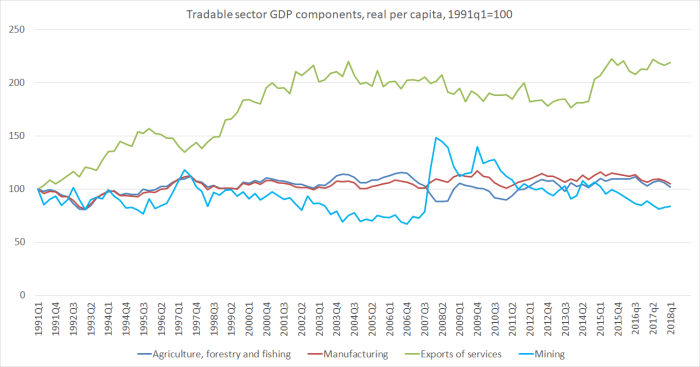

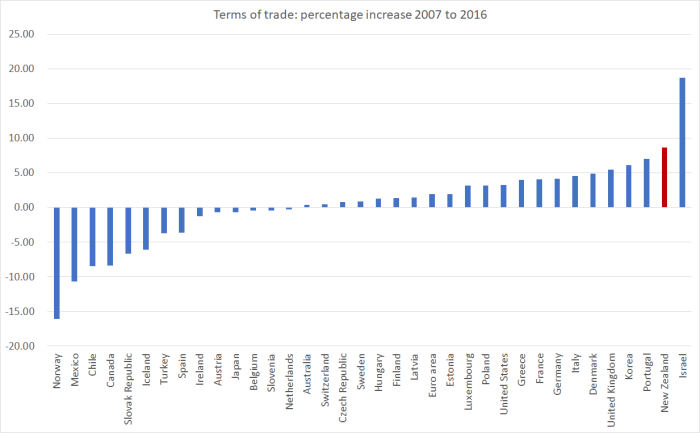

The terms of trade make a big difference to the government’s finances. Here is Treasury’s chart from this year’s Budget, illustrating how much help our unusually high terms of trade have been in recent years.

It is a real gain, but it is an exogenous windfall, not something any government or politician could simply conjure up.

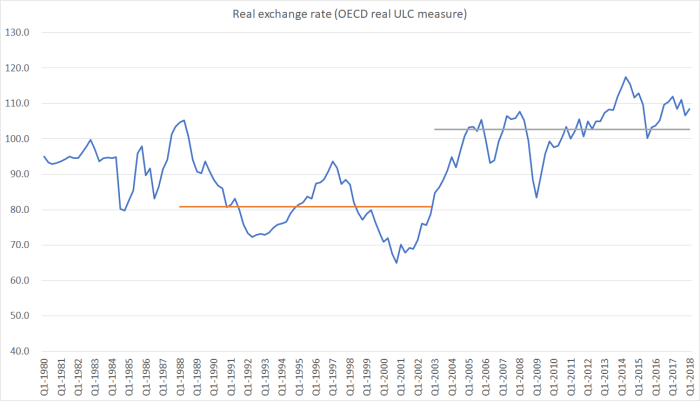

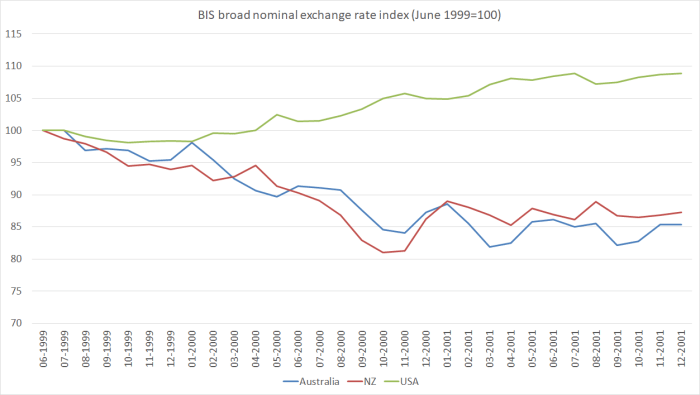

What about the official claim that Bill English was responsible for “steering New Zealand through the Global Financial Crisis”. It has become part of established rhetoric, but it has never been clear to me – and I was working at The Treasury at the time – that there was anything of substance to it. As ever, the biggest single contributors to getting New Zealand through this particular recession were (a) time, and (b) monetary policy. The crisis phase in other countries had been brought to an end by about March 2009 – initially as a result of extensive interventions in those countries (bailouts, fiscal stimulus, lower interest rates, and so on). That took the pressure off the rest of us. And our own, operationally independent, central bank had cut the OCR by 575 basis points by April 2009 (having begun to cut well before National took office in mid-November 2008), and some mix of the sharply lower interest rates, global risk aversion, and lower commodity prices had also lowered the exchange rate a lot. The Reserve Bank also put in place various liquidity assistance measures, at its own initiative.

What role then did New Zealand politicians play in “steering us through”? The previous Minister of Finance had put in place the deposit guarantee scheme, designed to minimise any risk of panicky runs on New Zealand institutions. I happened to think (having been closely involved) that was a good and necessary intervention, even if on important details the Minister departed from official advice, in turn increasing the later fiscal cost. On taking office, the new Minister of Finance, Bill English, made no material changes to the scheme, and took no material steps to rectify its weaknesses. Mr English did approve the (better-designed) wholesale guarantee scheme, designed to assist banks tap international wholesale funding markets in a period when those markets had largely seized up. It didn’t end up being extensively used, but was also the right thing to have done at the time.

What else was there? In the 2009 Budget – delivered after the crisis phase abroad had passed – a couple of rounds of tax cuts, promised in the 2008 election campaign (itself occurring in the midst of the crisis) were cancelled. That was prudent – given other fiscal choices the government had made – but there wasn’t anything extraordinary or particularly courageous about it. There was no discretionary fiscal stimulus undertaken in response to the crisis by either government – or nor was it needed, given the scope monetary policy here had.

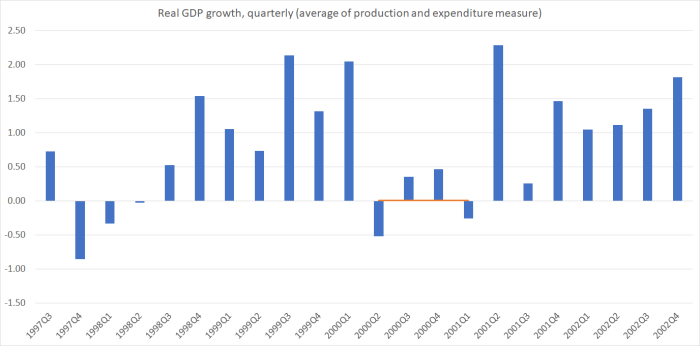

The truth of the international financial crisis of 2008/09 is that the New Zealand was largely an innocent bystander, caught in the backwash. There wasn’t much governments could, or did, do about it, and – to a first approximation – what they (Labour and then National) could do, they did. Both supported an operationally independent Reserve Bank and it, largely, also did what it could do (if, arguably, a bit slow to get off the mark). And then the storm passed and we started to recover, in a pretty faltering sort of way.

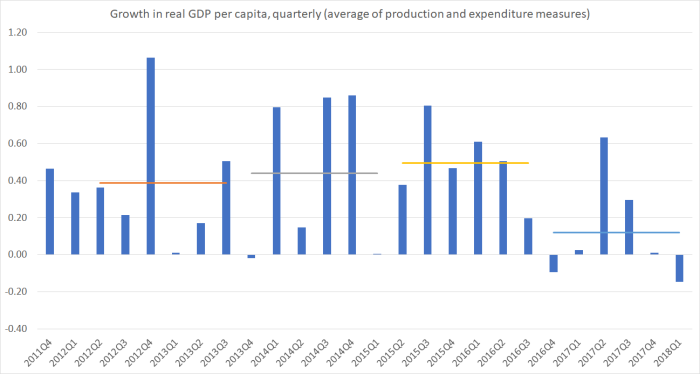

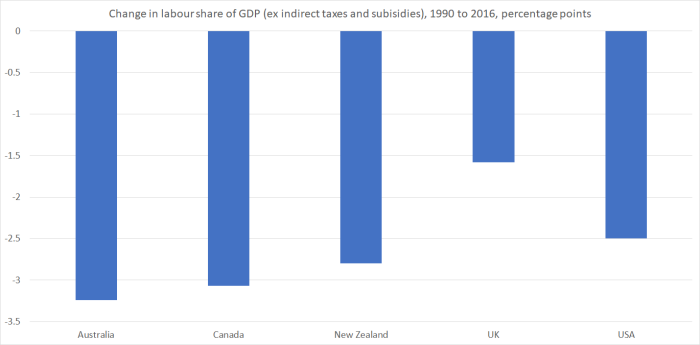

What about the other bit of that official citation, the claim that “as Finance Minister from 2008 until 2016, Mr English oversaw one of the fastest-growing economies in the developed world”? Why does the current Prime Minister continue to buy into this sort of nonsense – the myth (no, sheer falsehood) of the “rockstar economy”? To the extent the claim has any meaning at all, it simply reflects the much faster rate of population growth New Zealand experienced, especially in the last five years or so. Over that five year period (2012 to 2017), New Zealand’s real GDP per capita increased at almost exactly the rate of the median OECD country. Which is okay, I suppose, but nothing to write home about, especially once one remembers that we are poorer than most of these countries, and are supposed to have been trying to catch-up again.

But, one more time, let’s dig a little deeper.

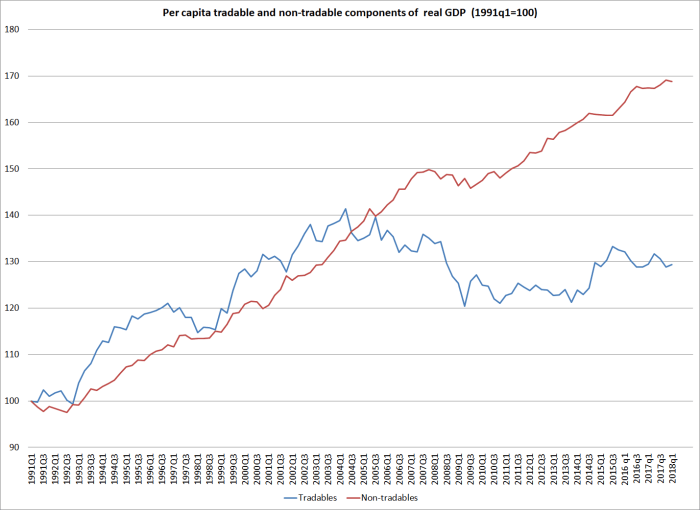

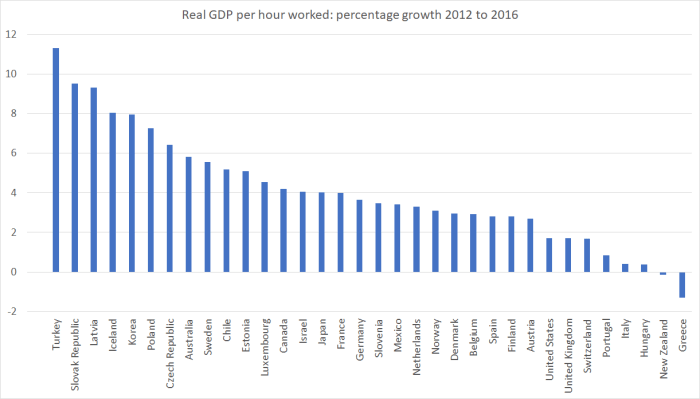

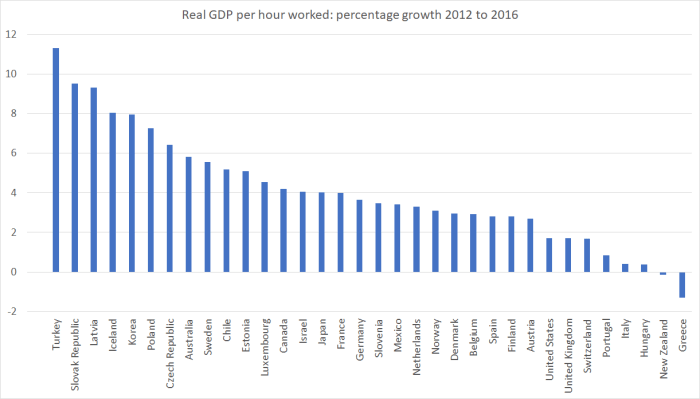

Productivity growth is the only sure foundation for sustained improvements in material living standards. Over the full period 2007 (just prior to the recession) to 2016 (the last year for which there is data for all OECD countries), New Zealand experienced labour productivity growth basically equal to that of the median OECD country. Again, perhaps not too bad, but no sign of any catching up. What about the last four years, the period to which most of the “rockstar economy” claims related?

Spot New Zealand – if you can – down next to Greece. And adding in 2017 – for which we have data, but some other countries don’t yet – would not improve the picture. Our recent productivity record – through the period presided over by Bill English (and John Key and Steven Joyce) – has been really bad.

What that means is that, to the extent that real GDP per capita growth has been middling, it has all been achieved by more inputs (mostly – since business investment is weak – more hours worked), not smarter better ways of doing things, old and new. Perhaps it really is a rockstar economy: a John Rowles or Cliff Richard one, belting out the same 1960s favourites over and over again? Recall that, being a poor OECD country, New Zealanders work more hours per capita than most other advanced countries do.

And despite more hours worked, it isn’t even as if we were particularly good at keeping the economy fully-employed during the English tenure. In this chart, I’ve standardised the unemployment rates of the G7 group of big advanced countries and of New Zealand so that both are equal to 100 in 2007q4, just prior to the recession.

Our unemployment rate went up about as much as the G7 countries (as a group) did, but just haven’t come back down anywhere near as much. For the G7 as a whole – which includes such troubled places as Italy and France, and is mostly made of countries that exhausted conventional monetary policy capacity – the unemployment rate is now lower than it was before the recession. But not in New Zealand.

Politicians don’t directly control the unemployment rate (or most of the other measures in this post), but it is pretty amenable to micro reforms, and (within limits) to monetary policy action. Under Bill English’s oversight, minimum wages kept on being raised, and nothing was done about a Reserve Bank that consistently kept monetary policy too tight (evidenced by the persistent undershoot of the inflation target set by the same Minister of Finance).

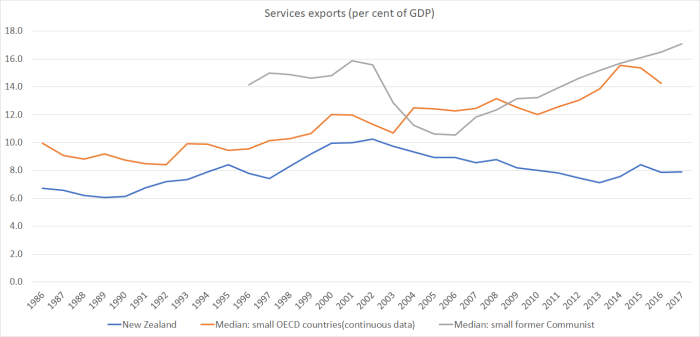

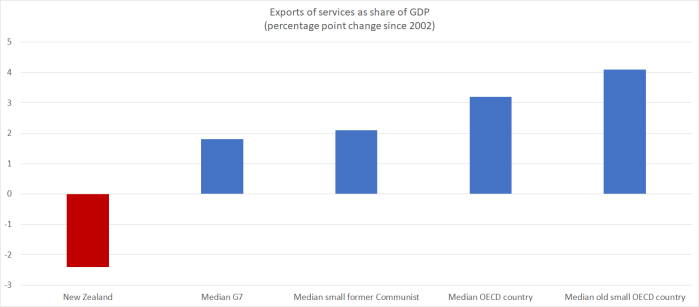

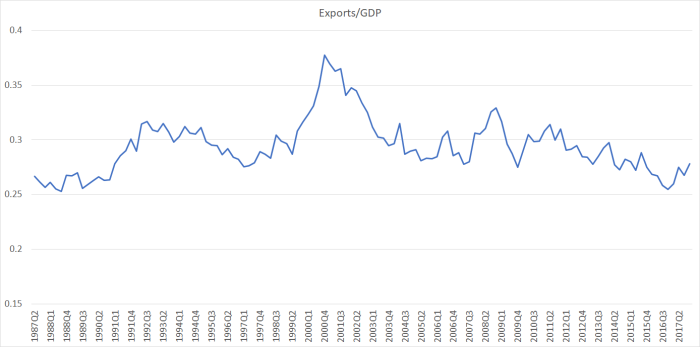

And what about foreign trade as a share of GDP? Successful economies tend, over time, to have a rising share of GDP accounted for by foreign trade (exports and imports). Small countries that succeed tend to have much larger foreign trade shares (since abroad is where the potential markets – and products – mostly are).

| Foreign trade as per cent of GDP |

|

|

2007 |

2016 |

| Exports |

New Zealand |

29.3 |

25.8 |

|

OECD median |

40.5 |

42.3 |

| Imports |

New Zealand |

29.1 |

25.5 |

|

OECD median |

39.2 |

39 |

But from just prior to the recession to 2016 (again the last year for which there is a full set of comparable data), New Zealand’s foreign trade shares shrank, even as those of the median OECD country held steady (imports) or increased (exports). Relative to our advanced country peers, our economy became more inward-focused.

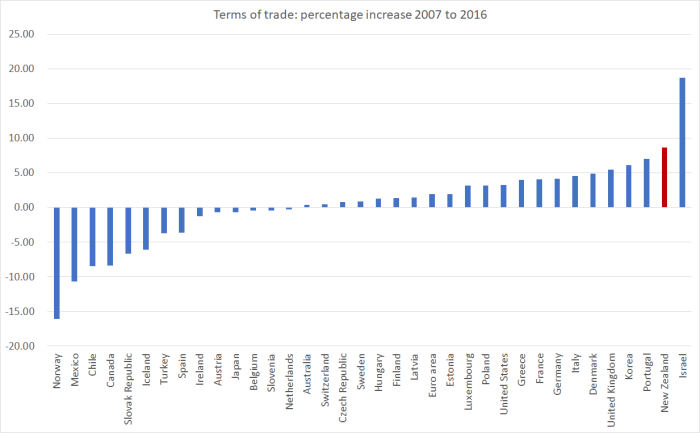

And that is despite the fact that we’ve had the second-largest increase in our terms of trade of any OECD country – very different from the other commodity exporters (Norway, Mexico, Chile, Canada, and even Australia).

Fortune favoured us, and we – our political leaders, the long serving Minister of Finance foremost among them – accomplished little with that good fortune.

Of course, not everything has been in New Zealand’s favour. We didn’t have a material domestic financial crisis, we weren’t locked into a dysfunctional single currency, we went into the lean years with a healthy fiscal position, we had more space to adjust conventional monetary policy than almost any other advanced country, and we’ve enjoyed a strong terms of trade. For enthusiasts for immigration, we’ve continued to draw in large numbers of permanent migrants, and have accelerated the inflow of temporary migrants.

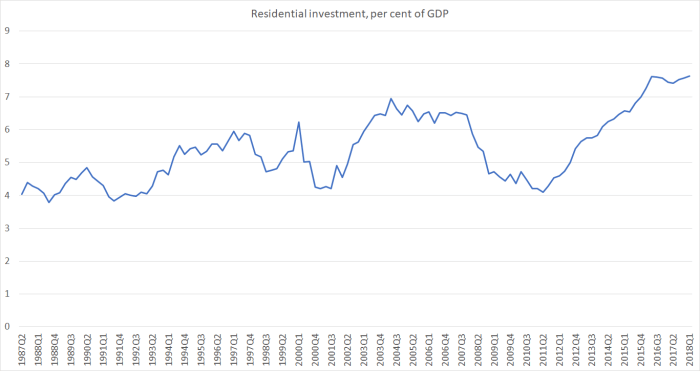

But there were the earthquakes. I’m not about to deny that they have held back economic performance, compelling resources to shift into domestically-oriented sectors, rebuilding (and inevitably/rightly so) rather than doing other things. But even the earthquakes need to be kept in perspective: they were seven years ago now, and in wealth terms were more than paid for by the combination of offshore reinsurance and the lift in the terms of trade. There is still no sign of things turning round now – of higher business investment, or a greater export orientation, of a recovery in productivity growth. It is just, at best, a mediocre story.

And did I mention house prices?

There are, of course, some other black marks against Bill English. There were the questions of integrity around the Todd Barclay affair. There was the willingness to lead his party into an election with a candidate who’d been part of the PRC military intelligence operation, and a member of the Chinese Communist Party, all things hidden from the electorate, and then to go on defending the indefensible as it became clear that important elements of this past had also been withheld from the immigration authorities.

But, even on his own ground – the economy – the record just doesn’t add up to much at all.

Oh, and as for the other top award that caught my eye yesterday, that was this astonishing one. I’ll probably write about that elsewhere. [UPDATE: Here for anyone interested in this non-economics issue.]