Five years ago, the then incoming Governor, Graeme Wheeler, signed a Policy Targets Agreement with the then Minister of Finance. In that document, he committed to run monetary policy with a

focus on keeping future average inflation near the 2 per cent target midpoint.

Earlier this week the CPI was published. It was the last such release that will appear while the Governor is still in office.

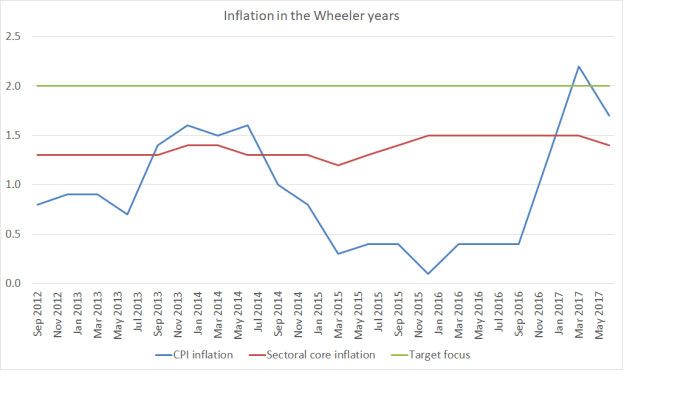

On a chart showing the 2 per cent focal point the Governor willingly committed himself and the Bank to, here are (a) the actual CPI inflation rates and (b) the Governor’s preferred measure of core inflation (the sectoral factor model measure) for the last five years.

Not once in five years has core inflation (on this measure) even come close to 2 per cent. In only a single quarter – one of 20 – did headline CPI inflation get to 2 per cent.

Of course, the Governor can’t really be held to account for inflation outcomes in the first year or so of his term – those outcomes were determined by choices made by Alan Bollard. And for the next year or so, it will be Graeme Wheeler’s policy choices that have the biggest policy influence. Nonetheless, to be so consistently far away from the newly-adopted target isn’t a great legacy. Perhaps (but probably not) the Bank’s Board will reflect on those outcomes in their forthcoming Annual Report?

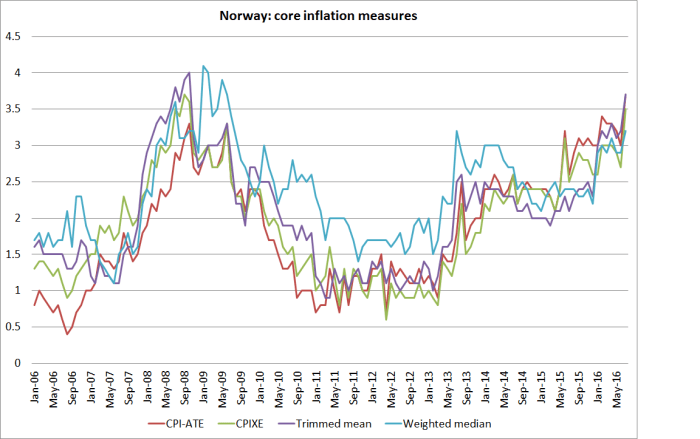

The sectoral factor model is only one measure of core inflation, albeit the most stable of them (and so the dip down in the latest release should be a bit disconcerting). Here is the table I’ve run previously, of six measures of core inflation.

| Core inflation: year to June 2017 | |

| CPI ex petrol | 1.7 |

| Trimmed mean | 1.8 |

| Weighted median | 2.0 |

| Factor model | 1.7 |

| Sectoral factor model | 1.4 |

| CPI ex food and energy | 1.6 |

| Median | 1.70 |

The poor track record on inflation might have been more tolerable if:

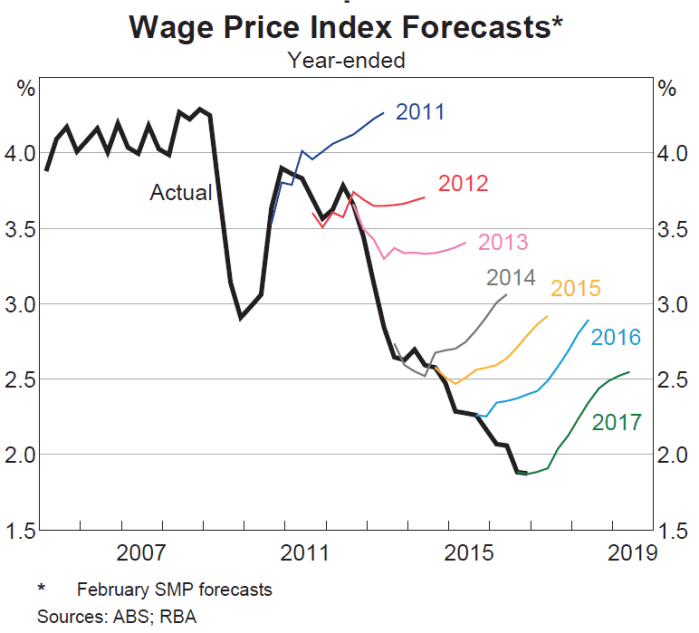

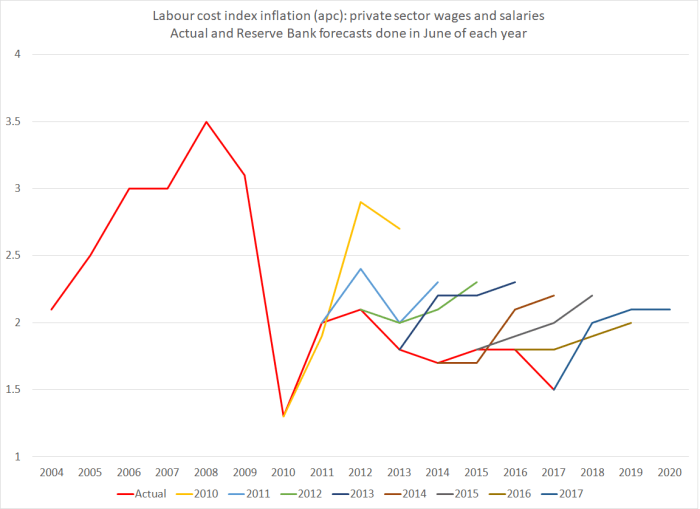

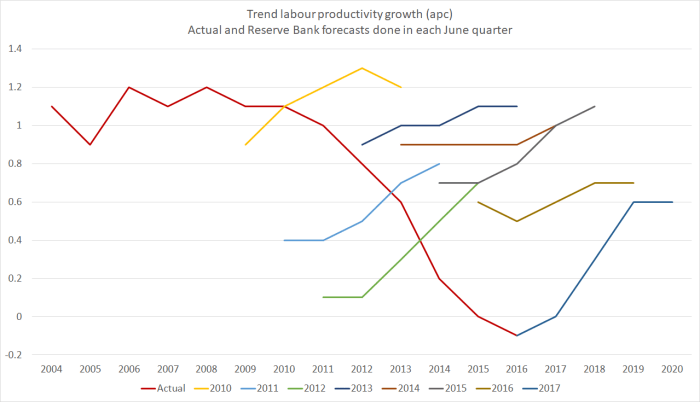

- productivity growth was really strong, driving down costs and prices. But it hasn’t been. In fact, there has been no labour productivity growth at all in the Wheeler years (not the Bank’s fault), or

- if the unemployment rate was exceptionally low. But it hasn’t been. The current unemployment rate (4.9 per cent) is still materially above most estimates of the NAIRU, and well above pre-recessionary levels. For what it is worth, it is also now above the unemployment rates in a couple of Anglo countries with pretty flexible labour markets (the US and the UK), which had to grapple with having reached the limits of conventional monetary policy during the post-recessionary years.

- core inflation was still rising now (mistakes happen, but fixing them promptly makes up for quite a lot). But, for example, the sectoral core measure is back to the same level it was in September 2015, when the Bank was just beginning to unwind its ill-judged 2014 tightenings.

Mostly, monetary policy in the Wheeler years hasn’t been well run. When Graeme Wheeler took office core inflation had fallen quite a bit over the previous year. A sensible response would have been to have cut the OCR. The OCR increases in 2014 were never necessary (I choose the word advisedly – there was plenty of time to wait and see if core inflation was in fact just about to pick up strongly). Those increases were then unwound only rather grudgingly.

Of course, in fairness to the Bank, it did rather less badly for most of the period than most of the market economists whose views are covered in the local media. For most of the time, most (almost all) of them were forecasting higher inflation, and a higher OCR, than the Reserve Bank was delivering. But it isn’t much consolation, since (a) the Reserve Bank has far more analytical resources at its disposal than the private banks, and (b) the Reserve Bank is paid to conduct monetary policy, and market economists aren’t.

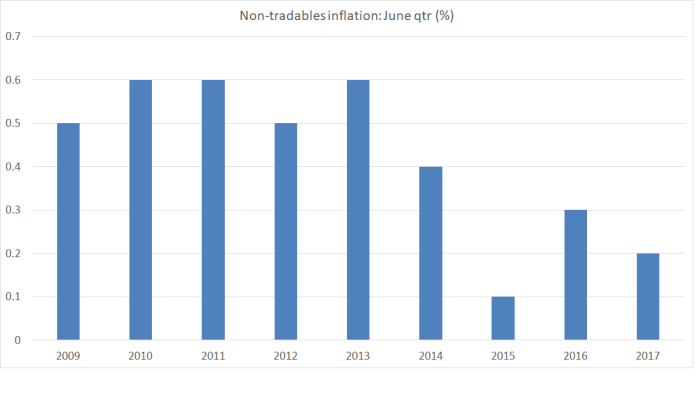

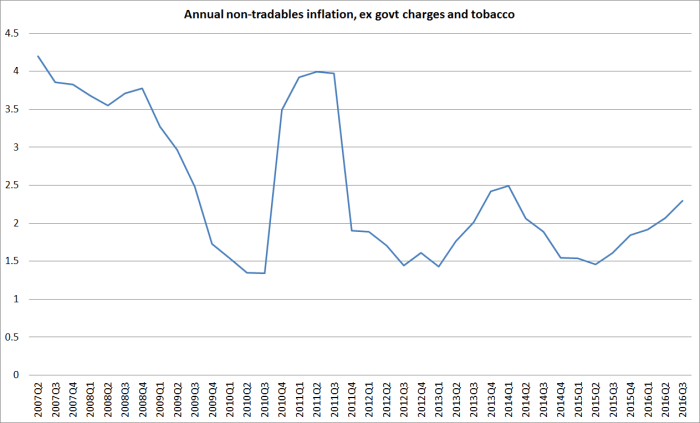

We’ll see next month what the Reserve Bank makes of the latest inflation outcomes. But the data must be quite disconcerting. There are some specific pockets of inflationary pressure – building costs notably (and not that surprisingly, given the population pressures). But here is non-tradables inflation (quarterly) for the June quarters of the last nine years. Non-tradables inflation is what the Reserve Bank has most influence over in the medium-term.

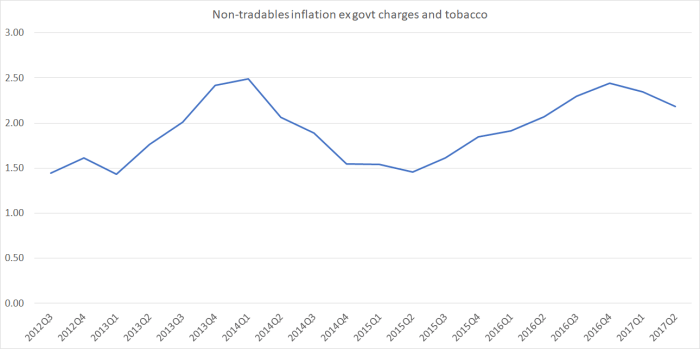

Only in 2015 was June quarter non-tradables inflation lower than it has been this year. Annual non-tradables inflation has dipped slightly to 2.4 per cent. That might not seem too bad – after all the target midpoint is 2 per cent – but as even the typically-hawkish BNZ noted in their commentary the other day one would really expect non-tradables inflation to be quite a lot higher to be consistent with delivering overall CPI inflation near the target midpoint. A simple approach to a core non-tradables inflation rate is the SNZ series that excludes government charges and the cigarettes and tobacco subgroup (where taxes are being raised substantially each year).

An annual inflation rate in this series nearer 3 per cent would be more consistent with core CPI inflation settling around 2 per cent. At present, it is nowhere near 3 per cent, and moving in the wrong direction.

So why is inflation still (a) quite a way from target, and (b) looking to be falling again? Broadly speaking, I reckon the answer is about (a) an economy that continues to run below capacity, and (b) tightening monetary and financial conditions. The Reserve Bank’s latest published estimate was that the output gap is around zero (roughly, a fully-employed economy). I noticed one local bank published an estimate the other day suggesting they thought the output gap was more like +1 per cent of GDP. With the unemployment hovering around 5 per cent – and best estimates of the NAIRU somewhere around 4 per cent, and demographic reasons to think the NAIRU might be falling, that simply seems unlikely. It is much more likely there is still some excess capacity in the system, and demand growth simply hasn’t been strong enough. The job of monetary policy is to manage interest rates in ways that deliver enough demand to keep inflation near target.

The current state of excess capacity is a long-running difference of opinion. But what isn’t really in much doubt is that monetary and financial conditions have been tightening quite substantially in the last few quarters.

The OCR was cut to the current level of 1.75 per cent last November. We might have expected inflation to pick up a little further since. But retail interest rates have been rising:

- the Bank’s measure of SME overdraft rates troughed in January 2017, and had risen by 19 basis points by June,

- the Bank’s measure of floating mortgage rates for new borrowers troughed in October 2016, and has risen 25 basis points since then,

- the Bank’s six month term deposit rate measure troughed in July last year and has risen 15 basis points since then,

- one and two year fixed mortgage interest rates are also up by around 20 basis points

These aren’t large moves, but with inflation having been consistently below target (and the Bank having been repeatedly surprised) there was no good reason for the Reserve Bank to have accommodated such tightenings.

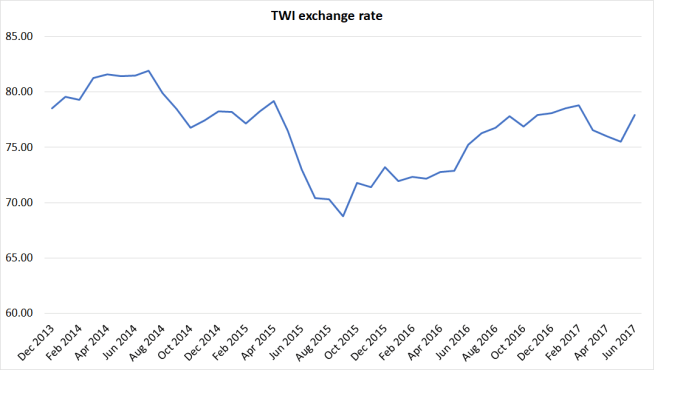

It isn’t just retail interest rates. Here is the trade-weighted exchange rate measure

The exchange rate fell quite a long way in 2015, as dairy prices fell, and the Reserve Bank began cutting the OCR. At the time, the Governor spun tales about how this would help get inflation back to 2 per cent. Exchange rates are somewhat variable, but broadly speaking the trend has been upwards since then. Yes, dairy prices and the terms of trade have improved, but it all adds up to another tightening of monetary conditions when inflation has been persistently below target.

And, of course, credit conditions have also tightened. Some of that is the Reserve Bank’s own doing – last year’s latest iteration of the LVR controls – but much of it isn’t: it is lenders reassessing their own willingness to lend. We don’t have good statistical indicators of credit conditions, but there is little doubt they’ve been tightening.

It all adds up to a picture in which shouldn’t really be very surprising at all: inflation isn’t rising and may well have begun falling again. Of course, some surprises reinforce the more systematic elements. Weaker oil prices (for example) probably will spill over to some extent into core measures of inflation. And unlike the situation in 2010 and 2014, this isn’t a case where the Reserve Bank has gone out actively seeking to tighten monetary conditions – indeed, the Governor has been commendably moderate, especially relative to most local market commentators. But it does look a lot like another case where the Bank (and the Governor personally, as single legal decisionmaker) has been too invested in a story that the economy was strong, inflation was picking up, and would continue to pick up, that it missed the way in which monetary conditions were tightening, and continued to largely (and deliberately) ignore the signals coming from the labour market. Instead of repeatedly talking – as the Governor does – about how accommodative (or even “highly accommodative”) monetary policy is, the Bank would be much better advised to treat the low level of interest rates as normal, for the time being (it has after all been more than 8 years now since they were sustainably higher), and put much more weight on seeing hard evidence that (a) inflation is settling back at around 2 per cent, and (b) unemployment is nearer credible estimates of the NAIRU, before acquiescing in any material tightening in monetary conditions. After getting it so wrong for so long, they should be willing to run the risk of core inflation heading a bit above 2 per cent for a time – after so many years of undershoots, no one is suddenly going to think the Bank is soft on inflation if core inflation is 2.2 or 2.3 per cent for a couple of years.

Looser monetary conditions now would, most likely, be more consistent with the Bank’s mandate. I’m not sure it is good form for the Governor to take the market by surprise with a cut from the blue as he heads out the door. But the case for establishing an easing bias in next month’s Monetary Policy Statement is beginning to strengthen. Hawks will, of course, cite the various business and consumer confidence measures. None is any stronger now than they’ve been over the last couple of years, and over that period inflation simply failed to pick up anything like enough to get back to target. Expecting something different now, when the background conditions haven’t changed, is either just wishful thinking, or something worse – including an inexcusable indifference to the lingering high number of people unemployed.

As we headed into the recession there was a lot of expectation of a strong rebound. Even up to around 2012, respondents expected growth to accelerate. For the last few years they haven’t expected any acceleration, and now the expect it to slow. To be specific, respondents expect 1.6 per cent total growth in the first half of this year, slowing to 1.2 per cent in the second half of this year. We don’t know quite why – perhaps they expect immigration numbers to slow – but it doesn’t speak of a sense that things are getting away on the Reserve Bank. Similarly, two years out respondents expected that the unemployment rate would still be 4.9 per cent.

As we headed into the recession there was a lot of expectation of a strong rebound. Even up to around 2012, respondents expected growth to accelerate. For the last few years they haven’t expected any acceleration, and now the expect it to slow. To be specific, respondents expect 1.6 per cent total growth in the first half of this year, slowing to 1.2 per cent in the second half of this year. We don’t know quite why – perhaps they expect immigration numbers to slow – but it doesn’t speak of a sense that things are getting away on the Reserve Bank. Similarly, two years out respondents expected that the unemployment rate would still be 4.9 per cent.

Perhaps there is some sign of a possible pick-up in the analytical unadjusted series (which doesn’t try to correct – inadequately – for productivity changes) but it is a moderately volatile series, and the most recent rate of increase is still below the peak in the last little apparent pick-up a year or two back.

Perhaps there is some sign of a possible pick-up in the analytical unadjusted series (which doesn’t try to correct – inadequately – for productivity changes) but it is a moderately volatile series, and the most recent rate of increase is still below the peak in the last little apparent pick-up a year or two back.

In both countries the current unemployment rate is around 1.5 to 1.7 percentage points higher than it was in the year or so prior to the global downturn. And neither country was troubled by a domestic financial crisis, nor did they run out of room to use conventional monetary policy. The monetary policy authorities should have been able to do better. If I look across the monetary areas in the OECD (again replacing individual euro area countries with the region as a whole), the only places with a worse record on this score – unemployment rates now compared to the pre-recession levels – are:

In both countries the current unemployment rate is around 1.5 to 1.7 percentage points higher than it was in the year or so prior to the global downturn. And neither country was troubled by a domestic financial crisis, nor did they run out of room to use conventional monetary policy. The monetary policy authorities should have been able to do better. If I look across the monetary areas in the OECD (again replacing individual euro area countries with the region as a whole), the only places with a worse record on this score – unemployment rates now compared to the pre-recession levels – are:

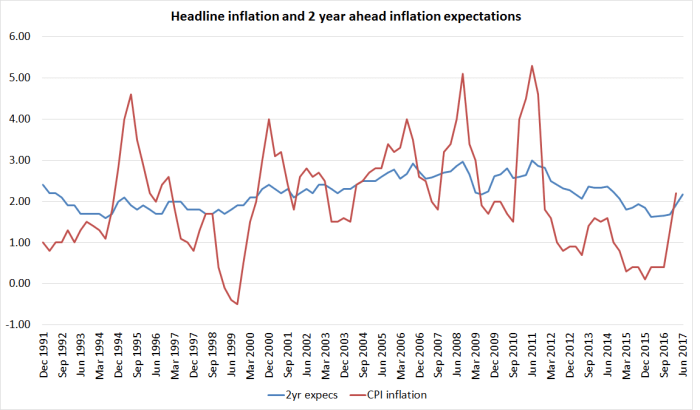

And here are two-year ahead inflation expectations in the two countries – the Reserve Bank survey for New Zealand, and a survey measure for Norway that I’ve taken from their MPS.

And here are two-year ahead inflation expectations in the two countries – the Reserve Bank survey for New Zealand, and a survey measure for Norway that I’ve taken from their MPS.