When, a couple of months ago, the current National-led government announced plans to tighten immigration policy in several areas, I summed up the changes as “a modest step that ignores the big picture“.

Yesterday, the Labour Party announced the immigration policy it will campaign on. I’d use exactly the same words to describe their proposals. Some of the changes – the largest ones – seem broadly sensible, but they won’t come close to tackling the real problems with New Zealand’s immigration policy.

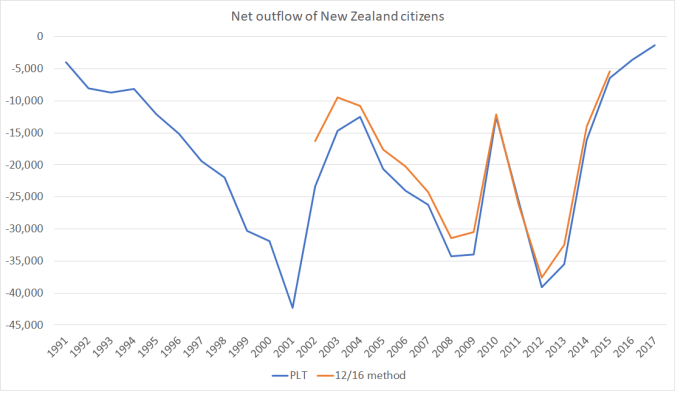

In some ways the biggest difference between the two parties’ approaches is that National provided us with no estimates about what impact their changes would have on numbers (and the Prime Minister apparently claimed yesterday they would, in fact, have no impact on numbers), while Labour is touting large numerical impacts but not acknowledging that they will actually have little or no medium to long-term effect on the net inflows of non-New Zealand citizens.

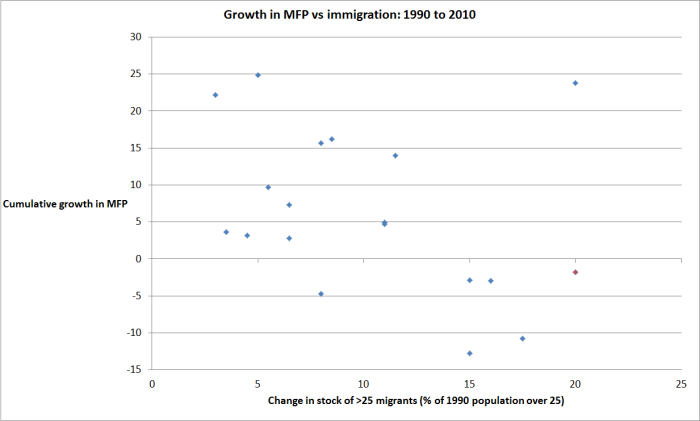

In many ways, none of this should be a surprise. The “big New Zealand” strategy, revitalised over the last 25 years, has been a bipartisan project. On either party’s policy, it remains one. There is really no material difference between them – just details which, while not unimportant, don’t affect the underlying strategy. A strategy which, to the extent it had an economic performance objective behind it (recall how MBIE used to call our immigration policy, “a critical economic enabler”), has simply failed. There is no reason to expect anything much better if future if we keep on with the same policies.

What determines the medium-term contribution of immigration policy to population growth is the residence programme, which aims to give out around 45000 residence approvals each year. The government cut that target a little last year. Labour’s policy doesn’t even mention it. At 45000 approvals, the programme is roughly three times the size, in per capita terms, of the equivalent programme is the United States (where about one million green cards are issued each year).

But what of the proposals Labour did put forward. Their policy document is here. It is misconceived from the first sentences where they state

Migrants bring to New Zealand the skills we need to grow our economy

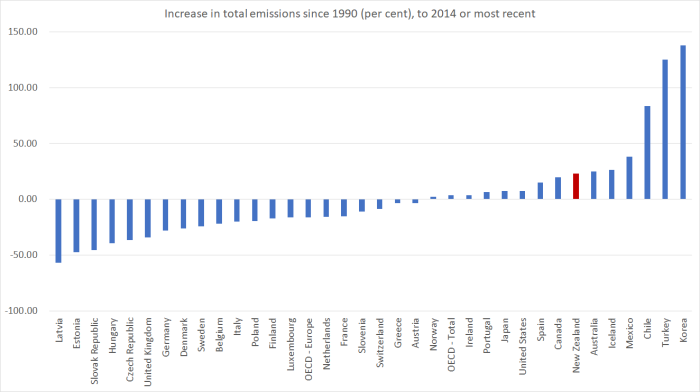

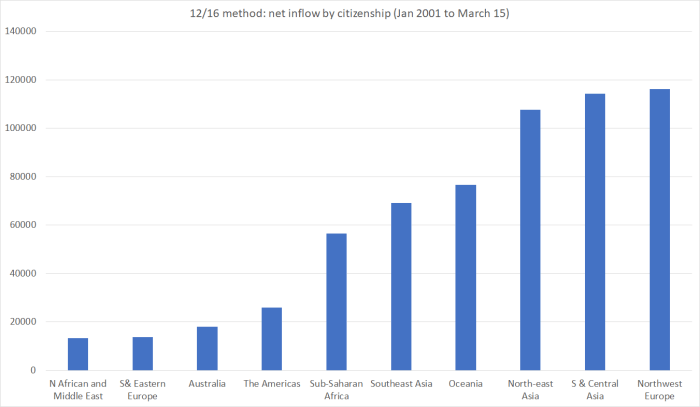

Have they not seen the OECD data showing that New Zealanders are among the most highly-skilled people in the advanced world, and that – on average – immigrants are a bit less skilled than natives? On the scale the New Zealand immigration programme attempts to operate at, the typical new additions to the labour force from non-citizen migration are not as highly skilled as the people who are already here, and our own young people who enter, and move up in, the workforce each year. There are, of course, no doubt some exceptionally talented people. But most are people from poorer countries looking for better opportunities here for themselves and their families – typically, too, people who couldn’t get into the richer and more successful Anglo countries. (None of this is a criticism of the migrants – pursing the best for themselves and their families is probably what all of us seek to do too – but it is a criticism of the policy framework that enables such large inflows of not overly-skilled people.)

Mostly Labour’s policy seems to be about fixing some pretty dubious changes made to the student visa system over recent years. In fact, three-quarters of the total numerical impact of their policy comes (on their own numbers) from student visa changes.

Labour will stop issuing student visas for courses below a bachelor’s degree which are not independently assessed by the TEC and NZQA to be of high quality.

Labour will also limit the ability to work while studying to international students studying at Bachelor-level or higher. For those below that level, their course will have to have the ability to work approved as part of the course.

Labour will limit the “Post Study Work Visa – Open” after graduating from a course of study in New Zealand to those who have studied at Bachelor-level or higher.

Mostly, those seem like a broadly sensible direction of change. That said, I’m slightly uneasy about relying on bureaucratic agencies to decide whether courses are “high quality” – in principle, surely the market can take care of reputational and branding issues?

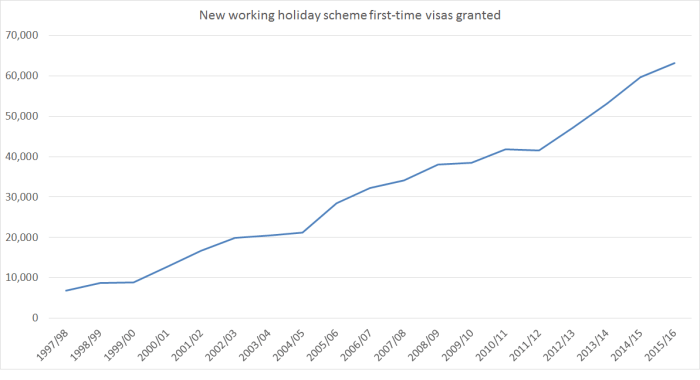

And while it might look good on paper, I’m a little uneasy about the line drawn between bachelor’s degree and other lines of study. It seems to prioritise more academic courses of study over more vocational ones, and while the former will often require a higher level of skill, the potential for the system to be gamed, and for smart tertiary operators to further degrade some of the quality of their (very numerous) bachelor’s degree offerings can’t be ignored. In the student visa data we already see some slightly suspicious signs (bottom right chart) of switching from PTEs to universities I’d probably have been happier if the right to work while studying had been withdrawn, or more tightly limited, for all courses. And if open post-study work visas had been restricted to those completing post-graduate qualifications.

Selling education to foreign students is an export industry, and tighter rules will (on Labour’s own numbers) mean a reduction in the total sales of that industry. Does that bother me? No, not really. When you subsidise an activity you tend to get more of it. We saw that with subsidies to manufacturing exporters in the 1970s and 80s, and with subsidies to farmers at around the same time. We see it with film subsidies today. Export incentives simply distort the economy, and leave us with lower levels of productivity, and wealth/income, than we would otherwise have. In export education, we haven’t been giving out government cash with the export sales, but the work rights (during study and post-study) and the preferential access to points in applying for residence are subsidies nonetheless. If the industry can stand on its own feet, with good quality educational offerings pitched at a price the market can stand, then good luck to it. If not, we shouldn’t be wanting it here any more than we want car assembly plants or TV manufacturing operations here.

Labour estimates that their changes to student visas and post-work study visas will reduce numbers by around 17000, roughly evenly split between the two classes of changes. But what they don’t tell you is that these will be one-off reductions in the total number of people here on those visas. Since the number of people who settle here permanently is determined by the residence approvals programme, and that hasn’t changed, the changes Labour is promising around student visas – while broadly sensible – while make a difference to the net migration flow in the first year they are implemented (the transition to the lower stock level) and none at all thereafter. They might change, a little, who ends up with a residence visa, but not how many are issued. If you favour high levels of non-citizen immigration but just want the “rorts” tidied up, it makes quite a lot of sense.

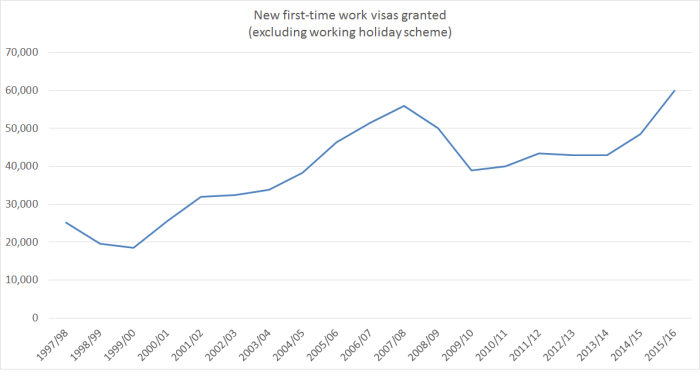

The changes Labour proposes to work visas are also something of a mixed bag. They are promising (but with few/no specifics) to make it harder for people to get work visas

Since 2011/12, the number of low-skill (ANZSCO 4 and 5) work visas issued has surged from 14,000 to 22,000. For example, the number of “retail supervisor” work visas has increased from 700 to 1,700. Labour will work with firms to train New Zealanders to fill skills gaps so we don’t have to permanently rely on immigration. A developed nation should be able to train enough retail staff to meet its own needs. Immigration should be a stop-gap to meet skills shortages, not a permanent crutch.

Labour will make changes that preserve and enhance the ability of businesses to get skilled workers to fill real skills gaps but which prevent the abuses of the system that currently happen.

The broad direction seems sensible enough – after all, the official rhetoric about the gains from immigration relate to really highly-skilled people, but what does it mean specifically?

And I get much more wary about proposals to move to a more regional approach (on top of the additional points for regional jobs the government introduced last year, thus further reducing the skill level of the average migrant). This is what they say:

Currently, few skill shortages are regionalised. This makes it hard for a region with a skills shortage in a specific occupation to get on the list if the shortage is not nationwide. Importantly it means that work visas are issued for jobs in regions where there is not actually a shortage which puts unnecessary pressures on housing and transport infrastructure there.

Labour’s regionalised system will work with local councils, unions and business to determine where shortages exist and will require that skilled immigrants work in the region that their visa is issued for. This will prevent skills shortages in one region being used to justify work visas in another, while also making it easier for regions with specific needs to have those skills shortages met.

Where skills shortages are identified, Labour will develop training plans with Industry Training Organisations so that the need for skilled workers is met domestically in the long-term. We will invest in training through Dole for Apprenticeships and Three Years Fees Free policies.

Frankly, it seems like a bureaucrat’s paradise, and just the thing for influential business groups that get the ear of some local council or other. It is hard enough to ensure that local authorities operate in the interests of their people, without setting up more incentives that will allow local authorities to be used to pursue the interests of one particular class of voters.

More generally, it is an approach that suggests no confidence at all in market mechanisms to deal with incipient labour market pressures. There is no suggestion in the document, at all, that higher wages might be a natural adjustment mechanism, whether to deal with increased demand in a particular region or for a particular set of skills. Even the Prime Minister was running that line recently – and he isn’t from the party supported by the union movement.

Again, changes to reduce the number of work visas granted to people for fairly low-skilled occupations aren’t a bad thing, but they won’t make any difference to the average net inflow of non New Zealanders beyond the initial (quite small) one-off level adjustment. And there is no willingness to rely on market mechanisms – eg set a (say) $15000 per annum fee, and allow limited work visas for jobs where the employer is willing to pay the taxpayer that additional price.

There were two other initiatives in the package. The first was the proposed new Exceptional Skills visa.

Labour will introduce an Exceptional Skills Visa. This visa will enable people with exceptional skills and talents that will enrich New Zealand society — not just its economy — to gain residency here.

It will be available to people who can show they are in an occupation on the long-terms skills list and have significant experience or qualifications beyond that required (for example, experienced paediatric oncologist) or are internationally renowned for their skills or talents. Successful applicants will avoid the usual points system requirements for a Skilled Migrant Category visa and would be able to bring their partner and children within the visa. This visa will help grow high-tech new industries, meet the increasingly complex needs of the 21st Century and enrich our society. Exceptional Skills Visas for up to 1,000 people, including partners and children, will be offered every year

When I first saw reference to this I was quite encouraged. And if it makes a little easier for people who are genuinely highly-skilled to get first claim on those 45000 residence approvals each year, then I don’t have any problem with it. But it isn’t exactly the American exceptional ability visa, and we need to be realistic about New Zealand’s relative attractiveness (or lack of it) to people with really exceptional talents. The suggestion that the programme will “help growth high-tech new industries, meet the increasingly complex needs of the 21st century” is probably little more than late 20th century vapourware.

As for the proposed KiwiBuild visas, I suppose they were politically necessary. You leave yourself open if you campaign on both big reductions in migrant numbers, and massive increases in house-building, if you don’t prioritise construction workers. In fact, of course, this programme makes a one-off reduction in the number of people here – reductions concentrated in the population group that probably has the least housing needs.. None of the medium-term pressures will have been eased at all, even if some dodgy rules around students do end tightened.

In passing, I was also interested in this comment

We will investigate ways to ensure that the Pacific Access Quota and Samoan Quota which are currently underutilised are fully met.

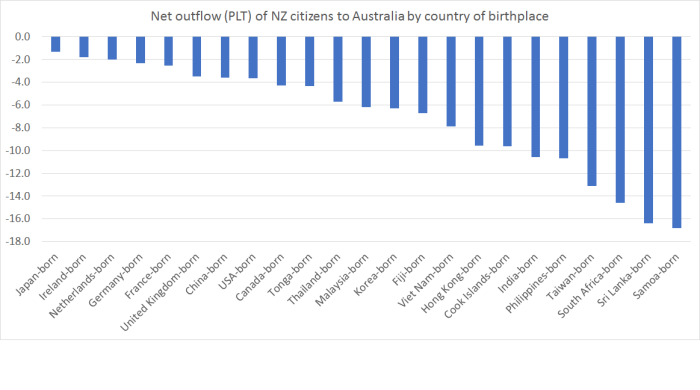

I guess there are really large numbers of Pacific voters in Labour’s South Auckland heartland. These Pacific quotas, again, lower the average skill level of those we given residence approval too (since people only come in on those quotas if they can’t qualify otherwise, all within the 45000 approvals per annum total). I imagine, too, that the Australian High Commission will have taken note of that line.

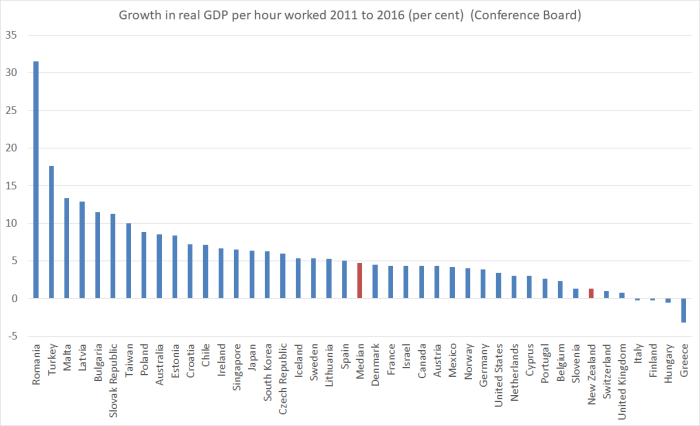

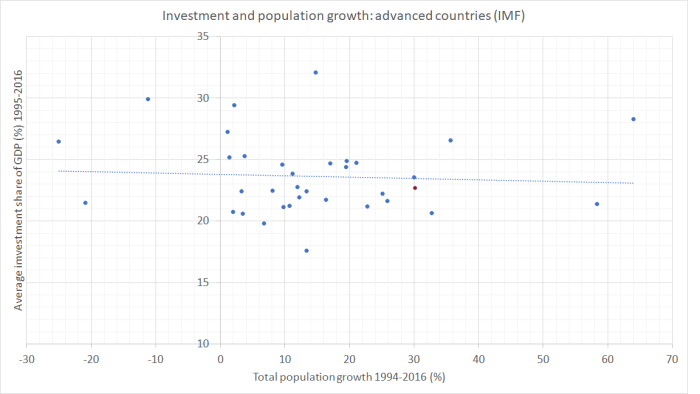

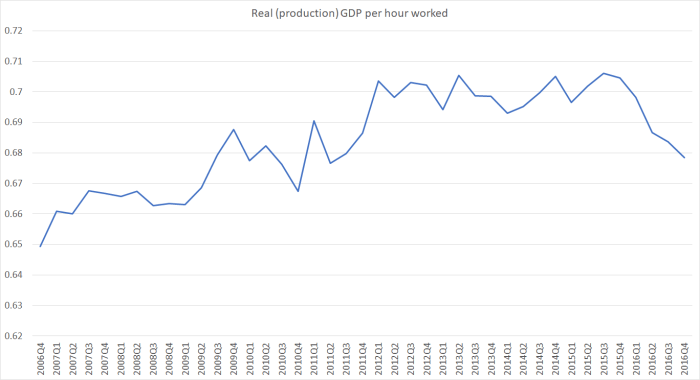

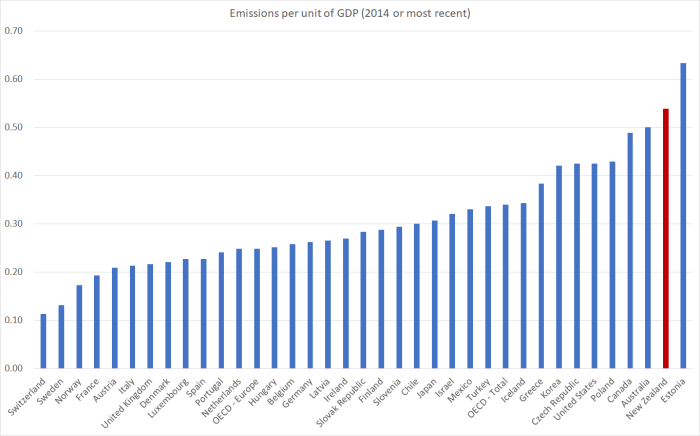

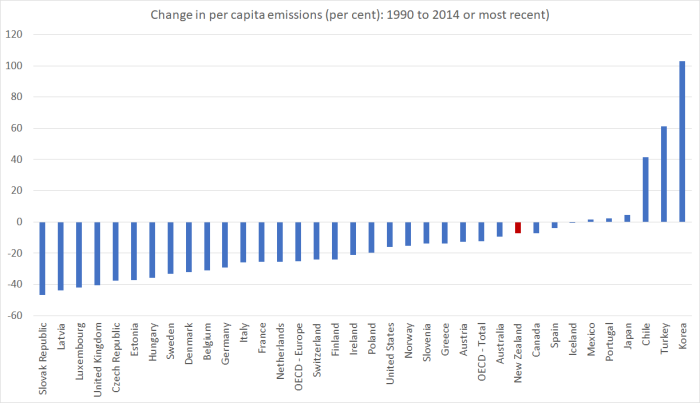

Overall, some interesting steps, some of which are genuinely in the right direction. But, like the government, Labour is still in the thrall of the “big New Zealand” mentality, and its immigration policy – like the government’s – remain this generation’s version of Think Big. And it is just as damaging. The policy doesn’t face up to the symptoms of our longer-term economic underperformance – the feeble productivity growth, the persistently high real interest and exchange rates, the failure to see market-led exports growing as a share of GDP, and the constraints of extreme distance. None of those suggest it makes any sense to keep running one here of the large non-citizen immigration programmes anywhere in the world, pulling in lots of new people year after year, even as decade after decade we drift slowly further behind other advanced countries, and se the opportunities for our own very able people deteriorate.

But that is Labour’s policy. And that is National’s policy.

For anyone interested, the Law and Economics Association is hosting a seminar on immigration policy and economic performance on Monday evening 26 June. Eric Crampton of the New Zealand Initiative and I will be speaking. Details are here.

UPDATE: Here is what I said to Radio New Zealand yesterday afternoon on immigration, in a reasonably extended interview, partly on Labour’s announcement, but mostly on the more general issues.