I spoke last night to the Nelson Property Investors’ Association. They’d asked me to talk about the Reserve Bank and the waves of new direct controls on housing finance that the Bank has put in place (or is positioning itself to put in place). Those controls have upended a liberalised and decentralised market that had been in place and functioning well, providing good access to credit without drama, for almost 30 years. Instead, we have now superimposed one man’s judgement.

It was a topic I was happy to talk about. It is certainly timely. In part that is because the current Governor’s term ends next month, and the person who gets the job next year as his permament replacement will materially influence the future direction of housing finance controls (although ideally governance reforms will materially reduce one person’s influence). But also because the Reserve Bank currently has a consultation document out, as part of a process to get the imprimatur of the Minister of Finance for possible use of debt-to-income regulatory limits. Submissions on the debt to income ratios proposal close next week and although I will be making a submission, last night’s address didn’t specifically focus on that proposal.

Much of my address was material I’ve covered before here. Nonetheless, in pulling it all together into a single (more or less) coherent story, I realised afresh just how poor the processes, background analysis, and the policies themselves have been. As it happens, at the meeting last night a representative of the NZ Property Investors’ Federation also spoke briefly, and his remarks were a reminder that poor quality policy certainly isn’t unique to the Reserve Bank. The difference perhaps is that we choose the politicians, and when governments do daft or dangerous things, we get to vote on tossing them out again. No such luck with the Reserve Bank. And, from my perspective, I write about things I know something about, and I’m pretty sure that the Reserve Bank was once considerably better than this. And could be again.

I began by looking back

When I was young and exploring job opportunities, I spent a day at the Reserve Bank. The then deputy chief economist was explaining the attractions of working at the Bank – things other than just the heavily-subsidised house mortgages. But the one line I remember was when he stressed the involvement the Reserve Bank had in the housing market, and issues around mortgage financing.

That wasn’t too surprising when one thinks about it. It was December 1982. We were coming towards the end of 40 years of pretty pervasive regulatory controls over so many aspects of the financial sector, including housing finance. The Reserve Bank was then a strong advocate in official circles for financial system deregulation, and allowing the market to take over the allocation of credit. It was – I thought then, and think now – on the side of the angels.

But in my first 20 or so years at the Reserve Bank housing was, at best, a very minor point of what we did. Within months, almost all the direct controls were stripped away. Institutions lent for housing if (a) they could fund themselves, and (b) if they could find (hopefully) creditworthy customers. It was their issue, not ours. Credit, generally, became more readily available. Interest rates trended back down, and banks typically became more willing to lend for longer terms. For an ordinary working person looking to buy a house, a very long repayment period will often make a lot of sense – just as a high initial LVR loan had always done.

And Parliament was careful to provide that whatever prudential powers the Reserve Bank did have were to be used not just to secure the soundness of the financial system, but also to promote the efficiency of that system.

But the bulk of the address focused on the weaknesses in what the Reserve Bank has been doing, in how it has made its case, and in the subsequent accounting for the impact of those controls:

- how they’ve never adequately engaged with the range of international experiences in 2008/09, fixating on the US and Irish experience when (a) Ireland was in the euro, so lost a lot of policy flexibility, and (b) the US has a long history of heavy government involvement in the housing finance market. Plenty of other advanced countries, including New Zealand and Australia, had big increases in house prices and housing credit, and no housing-driven financial crisis,

- how they continue to ignore the implications of their own successive waves of stress tests, which continue to show that even with very severe shocks the banking system appears to be resilient,

- they hardly ever engage on, and have produced no research on, the efficiency implications of direct controls, including on how they controls apply to banks and not non-banks, how they apply to housing lending but not other sorts of credit (even when past research suggests housing loans are rarely a key factor in systemic crises), and how the controls end up favouring riskier housing lending (new builds) over safer lending (on existing properties). Similarly, they’ve never engaged on the extent to which controls will impede the information discovery process implicit in different banks managing risks in different ways,

- there has been no evidence produced to explain why, in the Governor’s judgement, banks can be “trusted” to run their own credit policies in all other areas of their balance sheets, but just not in housing finance,

- they’ve produced nothing on the distributional implications of their policies – which tend to favour established low-leverage participants, at the expense of those looking to get into the market. These concerns only increase now that policies once sold as temporary are becoming increasingly longlived.

- despite assertions that the controls have reduced system risks, they’ve produced no analysis or research to make that case. Simply arguing that the volume of high LVR housing loans is lower (no doubt true), simply isn’t a satisfactory basis for such claims.

But, in a way, what concerns me at least as much as all this is that the Reserve Bank simply does not have a remotely adequate model of house prices. If they produced such a model (in words, or equations) we could carefully scrutinise it. If it was robust, we might even be inclined to defer to policy proposals based on that model. As it is, there is almost nothing – in public (and if they had such a model, they’d have every incentive to publicise it).

Consistent with this, the Bank’s house price, and implicit house price to income ratio, forecasts have been consistently and repeatedly wrong. They seem to put far too much weight on interest rates – while rarely acknowledging that interest rates are high (or low) for a reason, usually one to do with the expected growth potential of the economy. In much of New Zealand, reall house prices how are no higher, or even lower, than they were a decade ago when the OCR was at 8.25 per cent.

The Bank also seems to have an implicit model in which what has gone wrong is that building has lagged behind short-term unexpected changes in demand. No doubt it has to some extent, but the much the bigger issue – as most experts (and, I think, both main political parties) would now agree is land prices, themselves a product of land use regulatory restrictions (and associated infrastructure problems). These are no multi-decade phenomena, and show no sign of being resolved any time soon. When land is made artificially scarce by regulatory interventions in place for decades, which have not successfully been reversed anywhere else, what basis does the Bank have for (a) thinking that the house price issue is to any considerably extent an “overly liberal finance” problem, and (b) for supposing that a deep sustained correction – a halving of house prices – is a serious possibility? On their published material, none at all.

Instead of a good rich model, and a nuanced understanding of the housing market, all we are given is the extreme reduced-form, of “what goes up, must come down again”. Well, perhaps one day, but regulated prices can stay well out of line with unregulated fundamentals for a very long time – see second hand cars in NZ in the 1950s onwards, or New York taxi medallions.

The absence of a richer basis of research and analysis to back these multi-year interventions should be deeply troubling. It simply isn’t how public policy should be made. It risks looking as though policy is based on one man’s whims.

I wrapped up this way

So we’ve ended up with highly invasive direct controls which mean that, for the first time in decades, ordinary borrowers need to worry about what the government might regulate next, instead of being free simply to deal with their bank on the intrinsic merits of their own project, or their own servicing capacity. Years on, there are no published criteria indicating when these temporary measures might be lifted – if anything, we seemed to be headed deeper into a morass of financing controls. And all this has been done based on no good evidence whatever – whether about crises, about housing, or about the housing finance market, which had seemed to most involved to be working just fine. It is bad enough when they don’t publish analysis. What is scarier is that the really don’t seem to know. It is so far from being an acceptable standard that probably no one could have envisaged this happening even 10 years ago.

How did this sad state of affairs come to be?

Good systems of governance avoid putting very much power in one person’s hands. But by law, the Governor could do all this on a whim. We don’t run other state agencies or our court system that way.

We had a Board of the Reserve Bank that did nothing when the Governor they appointed started running off the rails.

We have banks that are scared to speak out, or take on the regulator.

We have a Parliament that isn’t willing to do its job – holding to account the man, and institution, to whom they gave so much power.

Events matter too. Those crisis-ridden months of 2008/09 rightly prompted a “never let it happen here” mentality. But it was a knee-jerk reaction, with no analysis looking carefully at why it hadn’t happened here. It seemed to provide an open field for enterprising interveners.

And then there were the NZ specific events: the huge and unexpected population surge, all amid governments (and oppositions) willing to do almost nothing to fix the underlying dysfunction in the housing and urban land supply market. “Someone needs to do something” was the mood. Well, the Reserve Bank was “someone” and LVR controls were “something”. Never mind that they might have nothing to do with the underlying housing problem, and respond to financial stability problems that RB numbers suggest just don’t exist.

Sadly, we’ve upped the returns to lobbying, and to keeping sweet with the regulator – incentives only accentuated by episodes like the Toplis affair. Evidence is that the Bank doesn’t welcome debate, or challenge, or scrutiny, and could well try to take it out of your hide. That means even less serious scrutiny of the Bank than we might once have hoped for.

And so one thing piled on top of another, and a single person at the head of a once well-regarded body gets let loose to pursue his (questionably legal) whims, and mess up our well-functioning housing finance market, all while pontificating idly (without thoughtful background research or analysis) on a steadily worsening housing crisis. I’m sure he has good intentions – about saving us all from ourselves – but no mandate, no analysis or evidence, no accountability. Just whim.

Shortly, the one man will be off. And we – citizens, savers, actual and potential borrowers – will be left to live with the consequences. We can only hope that whoever takes up the role of Governor next year, does so with a quiet determination to begin unpicking the mess, allowing the market in finance to work properly – as it had been doing in recent decades – and building an institution known for the excellence of its analysis, operations and policy. Perhaps the new improved Bank may even be able to offer some compelling insights on the regulatory disaster that our housing market – in common with those in many other similar countries – has become.

But I’m not hopeful about any of this. Politicians seem not to care. And powerful officials typically rather like the degree of power they enjoy. Why take the risk, they might well say, of removing controls. Why not just trust us, we know what we are doing.

There were a couple of questions that helped shed light on my story.

One asked how different things would look if we’d simply stuck with the deregulated finance market and not put on any of the LVR controls.

My response was “not much”, at least on the house price front. As the Reserve Bank itself will openly state, they don’t think LVR restrictions make much sustained difference to house prices. You might get six months “relief”, perhaps even twelve months, but before long the structural fundamentals – population pressures on the land-supply constrained market – reassert themselves. Perhaps in total house prices are still a couple of per cent lower than they might otherwise have been, but no one can tell with any confidence. What we can be reasonably confident of is that different people own the houses: fewer new entrants, and more owned by establishment players. So much for the democratisation of finance that the 1980s reforms made possible.

Of course, there would probably be a larger stock of higher LVR loans – and banks would be holding more capital against those loans. But since we don’t adequately understand what banks have chosen to do instead of the high LVR loans they are barred from, we don’t even know have different the risk profile of their balance sheets would look, let alone whether they were more at risk of some future crisis. (I would also note that had the Reserve Bank done nothing, the less direct guidance to the Australian banks from APRA would no doubt have influenced lending patterns here).

And the second was along the lines of what I might have done in Graeme Wheeler’s place. My short answer was “nothing”. There is no evidence that the housing “crisis” is, to any material extent, a phenomenon of inappropriately loose finance, and there is no evidence that banks here have systematically been making poor judgements about the allocation of (housing) credit. I’d have been reassured by the stress tests – in fact, I still recall going to an internal seminar, perhaps in 2014, when the results of the stress tests were first presented. I, among others, didn’t want to believe them, but despite all the pushback and probing, the results appear to have been robust. Keep doing the stress tests, and when those results look worrying that is the time to consider further action.

None of that is a story of indifference to the problems of a dysfunctional housing supply and urban land market. But problems need to be correctly diagnosed, and appropriate remedies applied. Appropriate remedies to the housing market failures rest squarely with central and local government, not with the Reserve Bank. Research resources are scarce, but there might even have been a case for the Reserve Bank to have invested in becoming something of a centre of excellence in housing, housing finance, and the economics of land use. In some respects, it isn’t core Reserve Bank business, but it is hard to argue that it would be inappropriate for the central bank to develop and maintain structured expertise in a market that represents that main form of collateral for the banking system. We don’t want our Reserve Bank, or the Governor, politicised, but a high-performing central bank, with an established reputation for objective excellence, could nonetheless have made a valued contribution to a better debate, and better policy responses, to the lamentable situation that is New Zealand housing. Perhaps, with a different Governor, they still could.

Anyway, the full text of my address is here. We are entitled to expect better from such a powerful public agency.

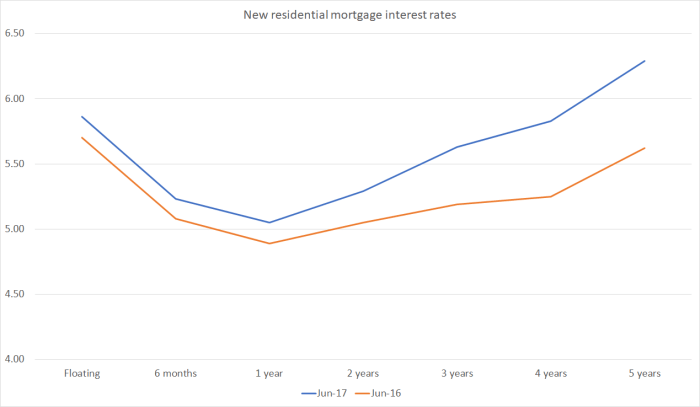

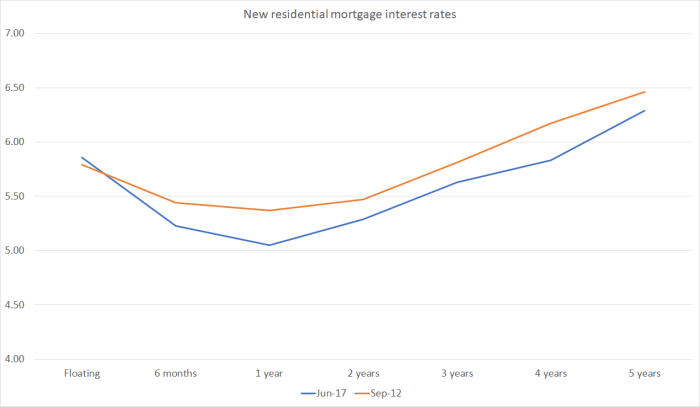

I don’t suppose anyone is taking out four or five year fixed rate mortgages, but across the entire curve, interest rates are higher not lower. Or we could go back another year or so, to just prior to when the Reserve Bank began cutting the OCR. The OCR has been cut by 175 basis points since then. Even at the shortish end of the mortgage curve, rates are down only 50-70 basis points.

I don’t suppose anyone is taking out four or five year fixed rate mortgages, but across the entire curve, interest rates are higher not lower. Or we could go back another year or so, to just prior to when the Reserve Bank began cutting the OCR. The OCR has been cut by 175 basis points since then. Even at the shortish end of the mortgage curve, rates are down only 50-70 basis points. Barely lower, even though core inflation – on their own favoured measure – is as low today as it was then (and has been consistently low throughout his term).

Barely lower, even though core inflation – on their own favoured measure – is as low today as it was then (and has been consistently low throughout his term).