The Reserve Bank Governor appears to have been communing with his tree gods again, and last week released a speech he’d delivered online to an overseas audience headed “Why we embraced Te Ao Maori”. It isn’t clear quite how many people were in the audience for this commercial event run by the Central Banking (private business) publications group, but I’m guessing not many. The stream Orr spoke in featured just him, a panel discussion on how “digital finance can drive women’s inclusion”, and a presentation on “how can central banks put climate change at the core of the governance agenda”. While it was called the “governance stream”, a better label might be the woke feel-good stream, far removed from the purposes for which legislatures set up central banks.

In many ways, the smaller the overseas audience the better, and I guess his main target audience was probably domestic anyway. He claims to be keen on the concept of “social licence” (personally, I prefer parliamentary mandates, deliberately adhered to and closely monitored) and no such “licence” flows from second or third tier central bankers abroad.

There are several things that are striking about the speech. Sadly, depth, profundity or insight are not among them.

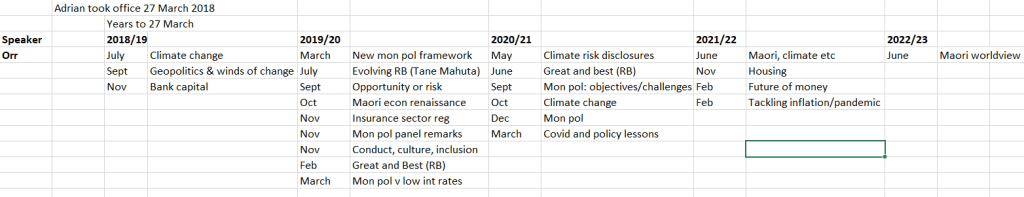

Orr has now been Governor for just over four years (his current term expires in March). In his time as Governor he has given 23 on-the-record speeches (fewer as time has gone on)

The speeches have been on all manner of topics – although very rarely on the Bank’s core responsibility, monetary policy and inflation, a gap that has become more telling over the last year or so. Unfortunately, coming from an immensely powerful public official, it is hard to think of any that are memorable for the valuable perspectives they shed on the Reserve Bank’s core policy responsibilities or its understanding of, and insights on, the macroeconomy and the financial system. His Te Ao Maori speech is no exception, and is probably worse than average. From a central bank Governor.

In the speech, we get several pages of a quite-politicised black-armband take on what might loosely be called “history”. Perhaps it will appeal to elements on the left-liberal electorate in New Zealand (eg the editors and staff on the Dominion-Post). I’m not going to try to unpick it – it simply has nothing to do with central banking or the Governor’s responsibilities – although suffice to say that if one wanted to traverse history in a couple of pages, one could equally choose quite different points to emphasise. In essence, we have the Governor using his official platform to (again) champion his personal politics. That is – always is, no matter the Governor, no matter their politics – inappropriate, and simply corrodes the confidence that should exist that the Reserve Bank is a disinterested player serving in a non-partisan way the narrow specific responsibilities Parliament has given it independence over.

The speech burbles on. The audience is reminded of the tasks Parliament has given the Bank to do

But this is immediately followed by this sentimental bumpf

But – and rightly – “environmental sustainability, social cohesion and cultural conclusion” (whatever their possible merits) are no part of the job of the Reserve Bank. Parliament identifies the Bank’s role and powers, not the Governor. And all this somehow assumes – but never attempts to demonstrate – that some (“a”) Maori worldview is better for these purposes that either some other “Maori worldview” or any other “worldview” on offer. As for the “long-term”, a key part of what the Reserve Bank is responsible for is monetary policy, where they are supposed to focus on cyclical management, not some “long term” for which they have neither mandate nor powers.

Get right through the speech and you’ll still have no idea what the Orr take on “a” Maori worldview is. Thus, we get spin like this

Except that, go and check out the Bank’s Statement of Intent from 2017, the year before Orr took office, and the values (those three i words) were exactly the same. All they’ve done is add some Maori translations on the front. If anything, it seems more like a Wellington public-sector worldview (“sprinkle around some Maori words and then get on with the day job”), but Orr seems to sincerely believe……something (just not clear what).

Then we get the repeat of the “Reserve Bank as tree god” myth. The less said about it the better (and I’ve written plenty before, eg here). But even if it had merits as a story-telling device, it is substance-free.

We get claims about “the Maori economy”. Orr cites again a study the Bank paid BERL to do, the uselessness of which was perhaps best summarised by the report’s author at a public seminar at The Treasury last year, of which I wrote briefly at the time

Even the speaker noted that “the Maori economy” is not a “separate, distinct, and clearly identifiable segment” of the New Zealand economy

The last few pages of the speech purport to tell readers about their Maori strategy. There are apparently three strands. First, is culture

To which I suppose one might respond variously (to taste), “well, that’s nice”, “what about other world views?” and “wasn’t that last paragraph rather suggestive of the public sector worldview above – scatter some words and get on”.

Then “partnering”

There is more of that, but none of it seems to have anything to do with the Bank’s statutory goals, it is more about officials using public money to pursue personal political objectives. Incidentally, it also isn’t obvious how any of it reflects “a Maori worldview”. I’d think it was quite a strange if the Reserve Bank were to delete “Maori” from all these references and replace, say, Catholics (another historic minority in Anglo-oriented New Zealand).

The final section is headed “Policy Development” and you might think you were about to get to the meat of the issue – here finally we would learn how “a” “Maori worldview” distinctively influences monetary policy, banking regulation, insurance regulation, payment system architecture, the provision of cash etc. The section is a bit long to repeat in full, but you can check the speech for yourself: there is just nothing there, of any relevance to the Bank’s core functions. Nothing. No doubt, for example, there are some real issues – and real cultural tensions – around questions of the ability to use Maori customary land as collateral, but none of it has anything to do with anything the Reserve Bank is responsible for. And nothing in the text suggestions any implications of this vaunted ill-defined Maori world view for the things the Bank is supposed to be responsible or accountable for. And still one would be left wondering why, if there were such implications, Orr’s personal and idiosyncratic take on “a Maori worldview” would take precedence over other worldviews, or (indeed) the norms of central banking across the world.

It is a little hard to make out quite what is going on and why. A cynic might suggest it was all just some sort of public service “brownwash”, designed to impress (say) the Labour Party’s Maori caucus and/or the editors and staff at Stuff. But it must be more than that. They seem sincere, about something or other. Recent minutes of the Bank’s Board meetings released under the OIA show that all these meetings now begin with a “karakia”, a prayer or ritual incantation. It isn’t clear which deities or spirits these incantations are addressed to, or whether atheists, Christian or Muslim Board members get to conscientiously object to addressing the spirits favoured by Messrs Orr and Quigley (the Board chair). But whoever they address, these meetings happen behind closed doors, only rarely given visibility through OIAs, so I guess we have to grant them some element of sincerity, about something or other.

But it seems to be about championing personal ideological agendas, visions of New Zealand perhaps, not policy that this policy agency is responsible for, all done using public funds, public time. And would be no more appropriate if some zealous Catholic-sympathising Governor were touting the importance of “a” Catholic worldview to this public institution, even if – as with the Governor and his “Maori worldview” – it made no difference to anything of substance at all. There is pomp and show, but nothing of substance that makes any discernible difference to how well or badly the Bank and the Governor do the job Parliament has assigned them.

Go through the Bank’s Monetary Policy Statements and the minutes of the MPC meetings. They might be (well, are) fairly poor quality by international standards, but there is nothing distinctively Maori, or reflective of “a Maori worldview” about them. Do the same for the FSRs, or Orr’s aggressive push a few years ago to raise bank capital requirements. Read the recent consultative document on the future monetary policy Remit, and there is nothing. Read – as I did – six months of Board minutes recently released under the OIA, and there is no intersection between issues of policy substance and anything about “a Maori worldview”.

The Bank has lost the taxpayer $8.4 billion so far (mark to market) on its LSAP position.

The Bank has published hardly any serious research in recent years

The Bank and the Minister got together to ban well-qualified people from being external MPC members

Speeches with any depth or authority on things the Bank is responsible for are notable by their absence.

We have the worst inflation outcomes for several decades

And we’ve learned that Orr, Quigley and Robertson got together and appointed to the incoming RB Board – working closely now on Bank matters – someone who is chair of a company that majority owns a significant New Zealand bank.

The Bank has been losing capable staff at an almost incredible rate, and now seems to have very few people with institutional experience and expertise in core policy areas

There is one failure or weakness after another. But there is no sign any of it has to do with Orr’s (non-Maori) passion for “a Maori worldview”; it is simply on him. His choices, his failures (his powers – the MPC is designed for him to dominate, and until 30 June all the other powers of the Bank rest solely with him personally). If the alternative stuff (climate change, alternative worldviews, incantations to tree gods) has any relevance, it is as a symptom of his unseriousness and unfitness for the job – distractions and shiny baubles when there was a day job to do, one that has recently presented the biggest substantive challenges in decades.

Shortly after the speech was delivered, another former Reserve Banker Geof Mortlock, who these days mostly does consultancy on bank regulation issues abroad, wrote to the Minister of Finance and the chairman of the Reserve Bank Board (copied widely) to lament the speech and urge Robertson and Quigley to act.

I agree with most of the thrust of what Geof has to say, and with his permission I have reproduced the full text below.

But asking Robertson and Quigley to sort out Orr is to miss the point that they are his enablers and authorisers. A serious government would not reappoint Orr. A serious Opposition would be hammering the inadequacies of the Governor’s performance and conduct on so many fronts. In unserious public New Zealand, reappointment is no doubt Orr’s for the asking.

Letter from Geof Mortlock to Grant Robertson and Neil Quigley

Dear Mr Quigley, Mr Robertson,

I am writing to you, copied to others, to express deep concern at the increasingly political role that the Reserve Bank governor is performing and the risk this presents to the credibility, professionalism and independence of the Reserve Bank. The most recent example of this is the speech Mr Orr gave to the Central Banking Global Summer Meetings 2022, entitled “Why we embraced Te Ao Maori“, published on 13 June this year.

As the title of the speech suggests, almost its entire focus is on matters Maori, including a potted (and far from accurate) history of the colonial development of New Zealand and its impact on Maori. It places heavy emphasis on Maori culture and language, and the supposed righting of wrongs of the past. In this speech, Orr continues his favourite theme of portraying the Reserve Bank as the Tane Mahuta of the financial landscape. This metaphor has received more public focus from Orr in the last two years or so than have the core functions for which he has responsibility (as can be seen from the few serious speeches he has given on core Reserve Bank functions, in contrast to the frequent commentary he makes on his eccentric and misleading Tane Mahuta metaphor).

For many, the continued prominent references to Tane Mahuta have become a source of considerable embarrassment given that the metaphor is wildly misleading and is of no relevance to the role of the Reserve Bank. For most observers of central bank issues, the metaphor of the Reserve Bank being Tane Mahuta fails completely to explain its role in the economy; rather, it confuses and misrepresents the Reserve Bank’s responsibilities in the economy and financial system. It is merely a politicisation of the Reserve Bank by a governor who, for his own reasons (whatever they might be), wants to use the platform he has to promote his narrative on Maori culture, language and symbolism.

If one wants to draw on the Tane Mahuta metaphor, I would argue that the Reserve Bank, as the ‘great tree god’ is actually casting far too much shade on the New Zealand financial ‘garden’ and inhibiting its growth and development through poorly designed and costed regulatory interventions (micro and macroprudential), excessive capital ratios on banks (which will contribute to a recession in 2023 in all probability), poorly designed financial crisis management arrangements, and a lack of analytical depth in its supervision role. Its excessive and unjustified asset purchase program is costing the taxpayer billions of wasted dollars and has fueled the fires of inflation. In other words, the great Tane Mahuta of the financial landscape is too often creating more problems than it solves, to the detriment of our financial ‘garden’. Some serious pruning of the tree is needed to resolve this, starting at the very top of the canopy. We might then see more sunlight play upon the ‘financial garden’ below, to the betterment of us all.

There is nothing of substance in Orr’s speech on the core functions of the Reserve Bank, such as monetary policy, promotion of financial stability, supervision of banks and insurers, oversight of the payment system, and management of the currency and foreign exchange reserves. Indeed, these core functions are treated by Orr as merely incidental distractions in this speech; it is all about the narrative he wants to promote on Maori culture, language, the Maori economy, and co-governance (based on a biased and contestable interpretation of the Treaty of Waitangi).

I imagine that the audience at this conference of central bankers would have been perplexed and bemused at this speech. They would have questioned its relevance to the core issues of the conference, such as the current global inflation surge, the threat that rising interest rates pose for highly leveraged countries, corporates and households, the risk of financial instability arising from asset quality deterioration, and the longer term threats to financial stability posed by climate change and fintech. These are all issues on which Orr could have contributed from a New Zealand perspective. They are all key, pressing issues that central banks globally and wider financial audiences are increasingly concerned about. Instead, Mr Orr dances with the forest fairies and devotes his entire speech (as shallow, sadly, as it was in analytical quality) on issues of zero relevance to the key challenges being faced by central banks, financial systems and the real economy in New Zealand and globally.

I have no problem with ministers and other politicians in the relevant portfolios discussing, in a thoughtful and well-researched way, the issues of Maori economic and social welfare, Maori language, and the vexed (and important) issue of co-governance. In particular, the issue of co-governance warrants particular attention, as it has huge implications for all New Zealanders. It needs to be considered in the light of wider constitutional issues and governance structures for public policy. But these issues are not within the mandate of the Reserve Bank. They have nothing to do with the Reserve Bank’s functional responsibilities. Moreover, they are political issues of a contentious nature. They need to be handled with care and by those who have a mandate to address them – i.e. elected politicians and the like. The governor of the central bank has no mandate and no expertise to justify his public commentary on such matters or his attempt at transforming the Reserve Bank into a ‘Maori-fied’ institution.

No previous governor of the Reserve Bank has waded into political waters in the way that Orr has done. Indeed, globally, central bank governors are known for their scrupulous attempts to stay clear of political issues and of matters that lie outside the central bank mandate. They do so for good reason, because central banks need to remain independent, impartial, non-political and focused on their mandate if they are to be professional, effective and credible. Sadly, under Orr’s leadership (if that is what we generously call it), these vital principles have been severely compromised. This is to the detriment of the effectiveness and credibility of the Reserve Bank.

What is needed – now more than ever – is a Reserve Bank that is focused solely on its core functions. It needs to be far more transparent and accountable than it has been to date in relation to a number of key issues, including:

– why the Reserve Bank embarked on such a large and expensive asset purchase program, and the damage it has arguably done in exacerbating asset price inflation and overall inflationary pressures, and taxpayer costs;

– why it is not embarking on an unwinding of the asset purchase program in ways that reduce the excessive level of bank exchange settlement account balances, and which might therefore help to reduce inflationary pressures;

– why the Reserve Bank took so long to initiate the tightening of monetary policy when it was evident from the data and inflation expectations surveys that inflation was well under way in New Zealand;

– how the Reserve Bank will seek to balance price stability and employment in the short to medium term as we move to a disinflationary cycle of monetary policy, and what this says about the oddly framed monetary policy mandate for the Reserve Bank put in place by Mr Robertson;

– assessing the extent to which the dramatic (and unjustified) increase in bank capital ratios may exacerbate the risk of a hard landing for the NZ economy in 2023, and why they do not look at realigning bank capital ratios to those prevailing in other comparable countries;

– assessing the efficacy and costs/benefits of macroprudential policy, with a view to reducing the regulatory distortions that arise from some of these policy instruments (including competitive non-neutrality vis a vis banks versus non-banks, and distorted impacts on residential lending and house prices);

– strengthening the effectiveness of bank and insurance supervision by more closely aligning supervisory arrangements to the international standard (the Basel Core Principles) and international norms. The current supervisory capacity in the Reserve Bank falls well short of the standards of supervision in Australia and other comparable countries.

These are just a few of the many issues that require more attention, transparency and accountability than they are receiving. We have a governor who has failed to adequately address these matters, a Reserve Bank Board that has been compliant, overly passive and non-challenging, and a Minister of Finance who appears to be asleep at the wheel when it comes to scrutinising the performance of the Reserve Bank. We also have a Treasury that has been inadequately resourced to monitor and scrutinise the performance of the Reserve Bank or to undertake meaningful assessments of cost/benefit analyses drafted by the Reserve Bank and other government agencies.

It is high time that these fundamental deficiencies in the quality of the governance and management of the Reserve Bank were addressed. The Board needs to step up and perform the role expected of it in exercising close scrutiny of the Reserve Bank’s performance across all its functions. It needs directors with the intellectual substance, independence and courage to do the job. There needs to be a robust set of performance metrics for the Reserve Bank monitored closely by Treasury. There should be periodic independent performance audits of the Reserve Bank conducted by persons appointed by the Minister of Finance on the recommendation of Treasury. And the Minister of Finance needs to sharpen his attention to all of these matters so as to ensure that New Zealand has a first rate, professional and credible central bank, rather than the C grade one we currently have. I would also urge Opposition parties to increase their scrutiny of the Minister, Reserve Bank Board, and Reserve Bank management in all of these areas. We need to see a much sharper performance by the FEC on all of these matters.

I hope this email helps to draw attention to these important issues. The views expressed in this email are shared by many, many New Zealanders. They are shared by staff in the central bank, former central bank staff, foreign central bankers (with whom I interact on a regular basis), the financial sector, and financial analysts and commentators.

I urge you, Mr Quigley and Mr Robertson, to take note of the points raised in this email and to act on them.

Regards

Geof Mortlock

International Financial Sector Consultant

Former central banker (New Zealand) and financial sector regulator (Australia)

Consultant to the IMF and World Bank