The possibility of a sustained rise in the inflation rate (internationally and here) has been getting a lot of attention in the last few months. Note that I call it a “possibility” rather than a “risk”, because “risk” often has connotations of a bad thing and, within limits, a rise in the (core) inflation rate is something that should be welcomed in most advanced economies where, for perhaps a decade now, too many central banks have failed to deliver inflation rates up to the targets either set for them (as in New Zealand and many other countries) or which they have articulated for themselves (notably the ECB and the Federal Reserve). I’m not here engaging with the debate on whether targets should be higher or lower, but just take the targets as given – mandates or commitments the public has been led to believe should be, and will be, pursued.

Putting my cards on the table, I have been quite sceptical of the story about a sustained resurgence of inflation. In part that reflected some history: we’d heard many of the same stories back in 2010/11 (including in the countries where large scale asset purchases were then part of the monetary policy response), and it never came to pass – indeed, the fear of inflation misled many central banks (including our own) into keeping policy too tight for too long for much of the decade (again relative to the respective inflation targets). Central banks weren’t uniquely culpable there; in many places and at times (including New Zealand) markets and local market economists were more worried about inflation risks than central banks.

I have also been sceptical because, unlike many, I don’t think large-scale asset purchases – of the sort our Reserve Bank is doing – have any very much useful macroeconomic effect at all (just a big asset swap, and to the extent that there is any material sustained influence on longer-term rates, not many borrowers (again, in New Zealand) have effective financing costs tied to those rates). And if, perchance, the LSAP programme has kept the exchange rate a bit lower than otherwise, it is hardly lower than it was at the start of the whole Covid period – very different from the typical New Zealand cyclical experience. In short, (sustained) inflation is mostly a monetary phenomenon and monetary policy just hadn’t done that much this time round.

Perhaps as importantly, inflation has undershot the respective targets for a decade or so now, in the context of a very long downward trend in real interest rates. There is less than universal agreement on why those undershoots have happened, in so many countries, but without such agreement it is probably wise to be cautious about suggesting that this time is different, and things will suddenly and starkly turn around from here. At very least, one would need a compelling alternative narrative.

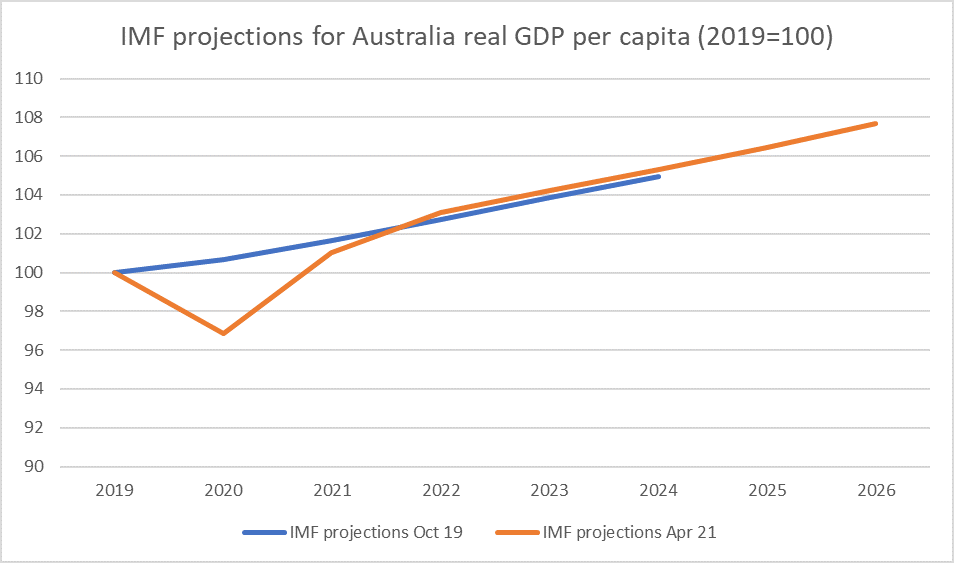

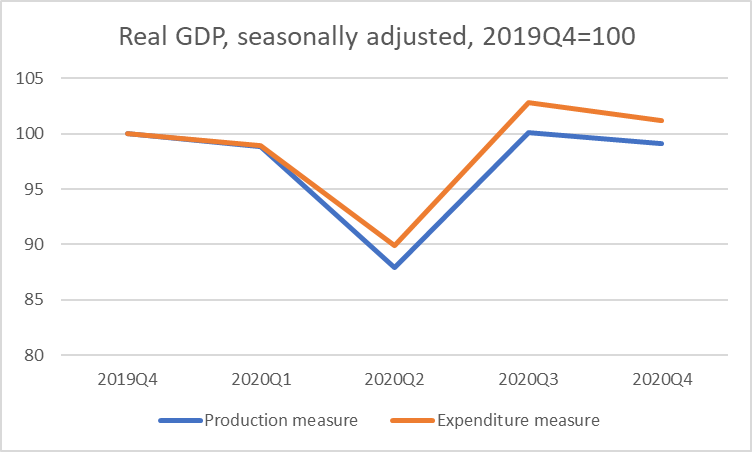

Having said that, there have been a couple of pleasant surprises in recent times. First, the Covid-related slump in economic activity has proved less severe (mostly in duration) than had generally been expected by, say, this time last year when some (including me) were highlighting potential deflationary risks. That rebound is particularly evident in places like New Zealand and Australia that have had little Covid, but is true in most other advanced countries as well where (for example) either the unemployment rate has peaked less than expected or has already fallen back to rates well below those seen, for example, in the last recession. Spare capacity is much less than many had expected.

And, in New Zealand at least, inflation has held up more than most had expected (more, in particular, than the Reserve Bank had expected in successive waves of published forecasts. The Bank does not publish forecasts of core inflation, but as recently as last August they forecast that inflation for the year to March 2021 would be 0.4 per cent (and that it would be the end of next year before inflation got back above 1 per cent). That was the sort of outlook – their outlook – that convinced me that more OCR cuts would have been warranted last year.

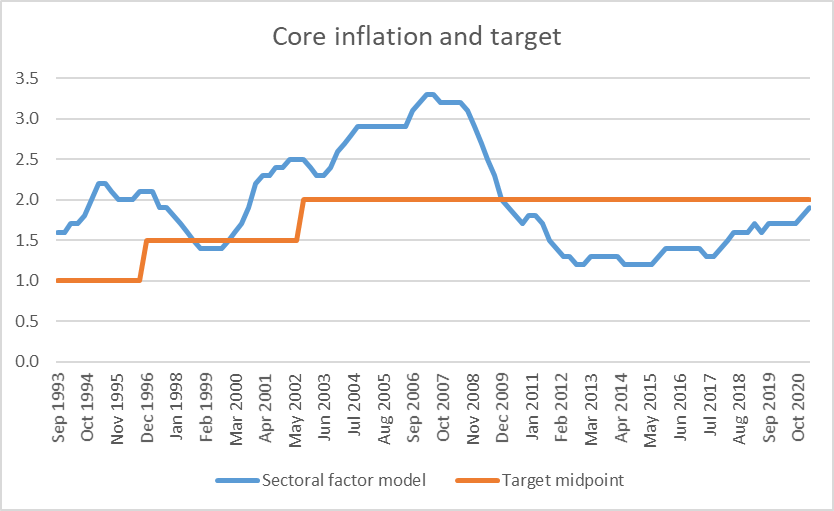

As it is, headline CPI inflation for the year to March was 1.5 per cent. But core measures are (much) more important, and one in particular: the Bank’s sectoral core factor model, which attempts to sift out the underlying trends in tradables and non-tradables inflation and combines them into a single measure: a measure not subject to much revision, and one which has been remarkably smooth over the nearly 30 years for which we now have the series – smooth, and (over history) tells a story which makes sense against our understanding of what else was going on in the economy at the time. This is the chart of sectoral core inflation and the midpoint of successive inflation targets.

It is more than 10 years now since this (generally preferred) measure of core inflation has touched the target midpoint (a target itself made explicit from 2012 onwards). With a bit of lag, core inflation started increasing again after the Bank reversed the ill-judged 2014 succession of OCR increases, but by 2019 it was beginning to look as if the (core) inflation rate was levelling-off still a bit below the target midpoint. It was partly against that backdrop that the Reserve Bank (and various other central banks) were cutting official rates in 2019.

The Bank’s forecasts – and my expectations – were that core inflation would fall over the course of the Covid slump and – see above – take some considerable time to get anywhere near 2 per cent. So what was striking (to me anyway) in yesterday’s release was that the sectoral measure stepped up again, reaching 1.9 per cent. That rate was last since (but falling) in the year to March 2010.

As you can, there is a little bit of noise in this series, but when the sectoral factor model measure of core inflation steps up by 0.2 percentage points over two quarters – as had happened this time – the wettest dove has to pay attention.

To be clear, even if this outcome is a surprise, it should be a welcome one. (Core inflation) should really be fluctuating around the 2 per cent midpoint, not paying a brief visit once every decade or so. We should be hoping to see (core) inflation move a bit higher from here – even if the Bank still eschews the Fed’s average inflation targeting approach.

Nonetheless, even if the sectoral factor model is the best indicator, it isn’t the only one. And not all the signs are pointing in the same direction right now. For example, the annual trimmed mean and weighted median measures that SNZ publishes – and the RBA, for example, emphasises a trimmed mean measure – fell back in the latest quarter. The Bank’s (older and noisier) factor model measure is still sitting around 1.7 per cent where it first got back to four years ago. International comparisons of core inflation tend to rely on CPI ex food and energy measures. For New Zealand, that measure dropped back slightly in March, but sits at 2 per cent (annual).

Within the sectoral factor model there is a non-tradables component – itself often seen as the smoothest indicator of core inflation, particularly that relating to domestic pressures (resource pressures and inflation expectations). And that measure has picked up a bit more. On the other, one of the exclusion measures SNZ publishes – excluding government charges and cigarettes and tobacco – now has an inflation rate no higher than it was at the end of 2019 and – at 2.4 per cent – probably too low to really be consistent with core inflation settling at or above 2 per cent (non-tradables inflation should generally be expected to be quite a bit higher than tradables inflation).

I think it is is probably safe to say that core inflation in New Zealand is now back at about 2 per cent. That is very welcome, even if somewhat accidental (given the forecasts that drove RB policy). As it happens, survey measures of inflation expectations are now roughly consistent with that. Expectations tend not to be great forecasts, but when expectations are in line with actuals it probably makes it more likely that – absent some really severe shock – that inflation will hold up at least at the levels.

But where to from here?

Interestingly, the tradables component of the Bank’s sectoral factor model has not increased at all, still at an annual rate of 0.8 per cent. All indications seem to be that supply chain disruptions and associated shortages, increased shipping costs etc will push tradables inflation – here and abroad – higher this year. But it isn’t obvious there is any reason to expect those sorts of increases to be repeated in future – the default assumption surely has to be that shipping, production etc gradually gets back to normal, perhaps with some price falls then.

And if one looks at the government bond market, participants there are still not acting as if they are convinced core inflation is going higher. If anything, rather the opposite. There are four government inflation-indexed bonds on issue, and if we compare the yields on those bonds with the conventional bonds with similar maturities, we find implied expectations over the next 4 and 9 years averaging about 1.6 per cent, and those for the periods out to 2035 and 2040 more like 1.5 per cent. Again, these breakevens – or implied expectations – are not forecasts, but they certainly don’t speak to a market really convinced much higher inflation is coming. One reason – pure speculation – is that with the Covid recession having been less severe than most expected, it isn’t unreasonable to think about the possibility of a more serious conventional recession in the coming years with (a) little having been done to remove the effective lower bound, and (b) public enthusiasm for more government deficits likely to reach limits at some point.

So I guess I remain a bit sceptical that core inflation is likely to move much higher here, even if the Reserve Bank doesn’t change policy settings. Fiscal policy clearly played a big role in supporting consumption last year but we are likely to be moving back into a gradual fiscal consolidation phase over the next few years. And if the unemployment rate is now a lot lower than most expected, it is still not really a levels suggesting aggregate excess demand (for labour, or resources more generally). For the moment too, immigration isn’t going to be providing the impetus to demand, and inflation pressures, that we often expect to see when the economy is doing well (cyclically). And if you believe stories about the demand effects of higher house prices – and I don’t- house price inflation seems set to level off through some mix of regulatory and tax interventions and the exhaustion of the boom (as in numerous previous occasions).

What should it all mean for monetary policy? Since I don’t think the LSAP programme is making much difference to anything that matters – other than lots of handwaving and feeding the narratives of the inflationistas who don’t seem to realise that asset swaps don’t create additional effective demand – I’d be delighted to see the programme canned. But I don’t think doing so would make much sustained difference to anything that matter either. So in a variant of one of the Governor’s cheesy lines, it is probably time for “watch, hope, wait”. The best possible outcome would be a stronger economic rebound, a rise in core inflation, and the opportunity then to start lifting the OCR. But there is no hurry – rather than contrary after a decade of erring on the wrong side, tending to hold unemployment unnecessarily high. And there is little or no risk of expectations – or firm and household behaviour – going crazy if, for example, over the next year or two core inflation were to creep up to 2.3 or 2.4 per cent.

But what of the rest of the world? I’ve tended to tell a story recently that if there really were risks of a marked and worrying acceleration in inflation it would be in the United States, where the political system seems determined to fling borrowed money around in lots of expensive government spending programmes.

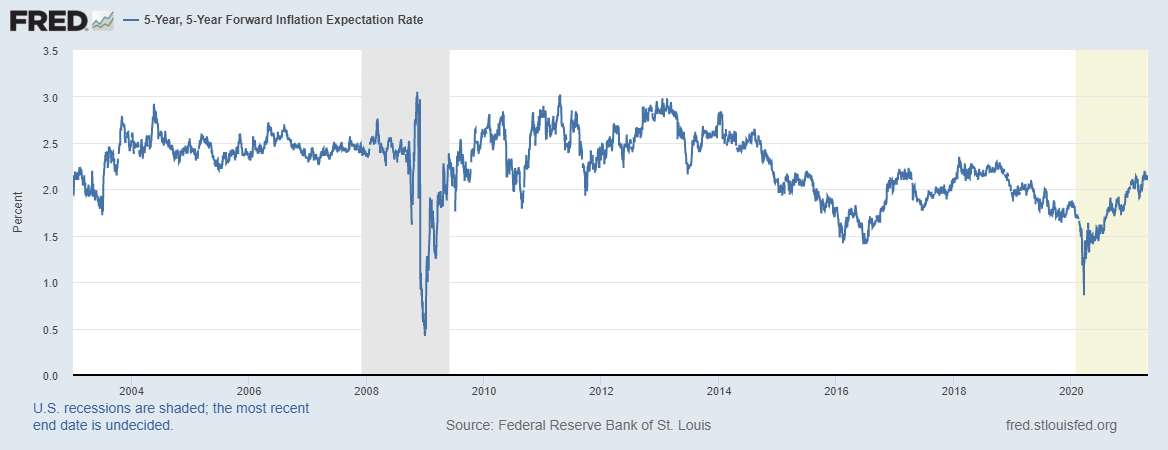

But for now, core inflation measures still seem comfortably below 2 per cent (trimmed mean PCE about 1.6 per cent). The Cleveland Fed produces a term structure estimate for inflation expectations, and those numbers are under 2 per cent for the next 28 years or so (below 1.7 per cent for the next 15 years). And if market implied expectations have moved up a lot from the lows last year, the current numbers shouldn’t be even remotely troubling – except perhaps to the Fed which wants the market to believe it will let core inflation run above 2 per cent for quite a while before tightening, partly to balance past undershoots. Here are the implied expectations from the indexed and conventional government bond markets for the second 5 years of a 10 year horizon (ie average inflation 6-10 years hence).

These medium-term implied inflation expectations are barely back to where they were in 2018, let alone where they averaged over the decade from about 2004 to 2014 – for much of which period the Fed Funds rate sat very near zero.

What of the advanced world beyond the US. It is harder to get consistent expectations measures, so this chart is just backward-looking. Across the OECD, core inflation (proxied by CPI inflation ex food and energy) has been falling not rising (these data are to February 2021, all but New Zealand and Australia having monthly data).

Are there other indicators? Sure, and many commodity prices are rising. And markets and economists have been wrong before and will – without knowing when – be wrong again. Perhaps this will be one of those times. Perhaps we’ve all spent too much time learning from the last decade, and forgetting (for example) the unexpected sustained surge in inflation in the 60s and 70s.

But, for now, I struggle to see where the pressures will come from. Productivity growth is weak and business investment demand subdued. Global population growth is slowing (reducing demand for housing and other investment). We aren’t fighting wars, we don’t have fixed exchange rate. And if interest rates – very long-term ones – are low, it isn’t because of central banks, but because of structural features – ill-understood ones – driving the savings/investment (ex ante) balance. For now, the New Zealand story is unexpectedly encouraging – inflation finally looks to be near target – but we should step pretty cautiously before convincing ourselves that the trends of the last 15 or even 30 years are now behind us, or that high headline rates – here and abroad – later this year foreshadow permanently higher inflation (or, much the same thing, higher required interest rates).