Early last month the new Secretary to the Treasury, Caralee McLiesh, gave her first on-the-record speech in the new role. The Treasury was a bit slow to release the text, but it is now available here. It wasn’t a long speech, but it was to a fairly geeky audience – the Government Economics Network’s annual conference – most of whom wouldn’t yet have seen much of the new Secretary. With not much else to go on yet, it seems reasonable to look at what she said for any indications of whether/how The Treasury is changing for the better under new leadership.

I’ve been uneasy about the new Secretary for several reasons:

- first, because she isn’t a New Zealander and has no background or experience in New Zealand issues or people, no domestic networks, and (most probably) little in-depth understanding of the idiosyncrasies of New Zealand, including its longrunning economic underperformance, and

- second, because she has no work experience in a national economic agency/ministry, dealing with national economic issues (financial crises, monetary policy, exchange rates, immigration, trade, or even very much exposure to fiscal or tax policies), and yet is now the principal economic adviser to our government (itself light on economic expertise or experience).

On the other hand, she has some fairly good academic qualifications and may well be quite capable as the sort of generic public service manager favoured by the current State Services Commissioner. Whether she can bring to the table more than that – and New Zealand economic policy, and The Treasury (weakened over the previous 10-15 years) needs more than that – remains to be seen.

The topic for the GEN Conference was “the role of regional and urban development in lifting living standards”. It is fair to say that my response to the title was along the lines of “there is no such role”, but it was still going to be interesting to see how the Secretary chose to respond to the topic, and perhaps to nest any specific insights on regional/urban issues in an understanding of the much bigger national productivity failings.

Of course, there are distinct limits to what serving senior public servants can and can’t say. One could argue they mostly shouldn’t be doing public speeches – their job is primarily to advise ministers, not to spin government PR (or to explicitly challenge it). But successive Secretarys have chosen to give speeches.

Here is McLiesh running spin for the government

The theme of today’s conference is how well-performing regions and cities can contribute to our wellbeing and raise living standards for all. Those of you familiar with the Government’s Economic Plan will know that the Government has identified ‘strong and revitalised regions’ as one of the key economic shifts it is working towards. And work on government’s urban growth agenda and resource management reforms is well underway. So this is a significant and substantial topic for New Zealand.

She, if no one else, I guess has to take the government seriously, at least in public, when it says it has a (30 year) Economic Plan.

But in the rest of speech there really wasn’t much substance. There was the best part of two pages recounting the Living Standards Framework – in text that is fine, but which offers nothing fresh. At least it ended with a reminder that economic performance matters

The Treasury always has an important role to play in advising government on how to lift economic productivity and performance, and this remains a core part of our LSF thinking. A roomful of economists doesn’t need to be told, but I will say it anyway, that high living standards depend on strong economic performance, and that markets that operate well – and I emphasise, “well” – can, and do, powerfully lift living standards. They enable people to participate in labour markets, earn higher incomes, and apply those incomes towards whatever wellbeing means for them. The story of development is basically a story about investment in the institutions and mechanisms that enable people to flourish in deep and complex markets – that is, to grow.

But really that should be “motherhood and apple pie” stuff to an audience of economists. And sadly, there hasn’t been much sign of rigorous or systematic advice on lifting productivity and economic performance in recent years.

She moves on to highlight that there are regional differences across New Zealand. There is quite a nice graphic drawing on OECD data, but she conveniently omits to highlight that (according to the graphic) not one New Zealand region has incomes in the top third of OECD country regions. Productivity is a huge failing in New Zealand, and that failing just isn’t region-specific. If anything, the gap between highest and lowest income regions within New Zealand is unusually small by OECD standards.

And thus when the speech says

Regions may contribute more to national economic development if we can tap unrealised economic potential. A policy approach that emphasises strengthening regional comparative advantage means we may be able to lift national economic performance rather than just shifting economic activity around the country.

it has the feel of someone who is stuck with the Provincial Growth Fund, rather than someone who has thought hard about New Zealand (and what does that counteractual – “just shifting economic activity around the country” – mean: who has been doing that?)

The next paragraph isn’t any better

There can be a role for government in helping communities to identify strengths and opportunities or strengthening local governance. There can be a role in working across agencies, local authorities, local people, and the private sector to coordinate and facilitate private investment. Or in investing in infrastructure where this directly unlocks economic opportunities. And can we do more to coordinate between social interventions and economic opportunities to ensure these approaches are complementary?

I guess bureaucrats would like to think so, but is there any evidence of governments being able to specifically catalyse regional economic development in a useful and sustainable long-term way, other than by getting the overall national policy settings right, and understanding the national failings?

There are some strange observations

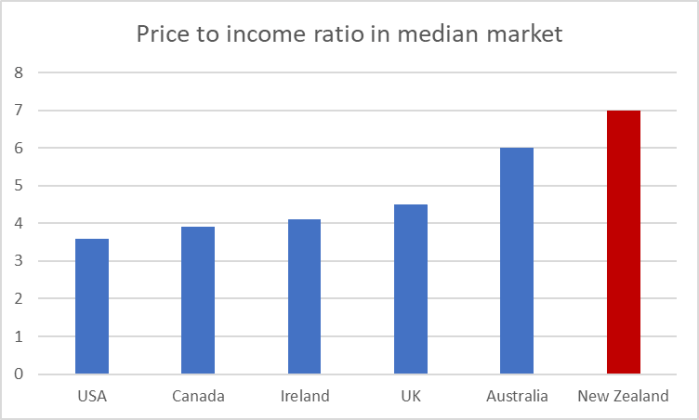

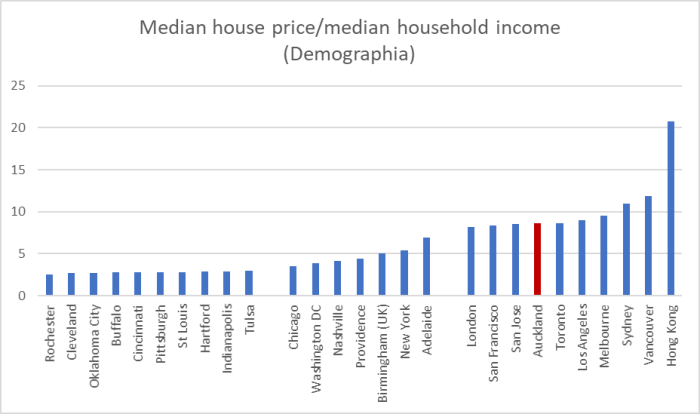

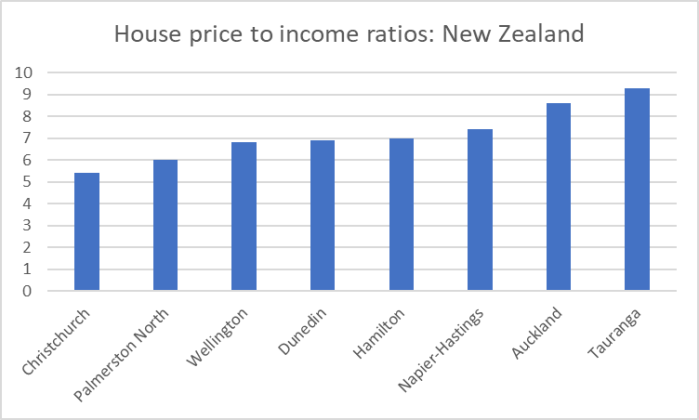

More than a third of New Zealanders live in Auckland, a city with house prices vastly in excess of the marginal cost of supply.

But house prices aren’t “vastly in excess of the marginal cost of supply”, rather national and local regulatory policies have driven the marginal cost of supply – especially the land component – well above where it would otherwise be, so that there is no huge gain on offer to people developing new houses.

It was encouraging to see the Secretary allude to Auckland’s longer-term economic underperformance

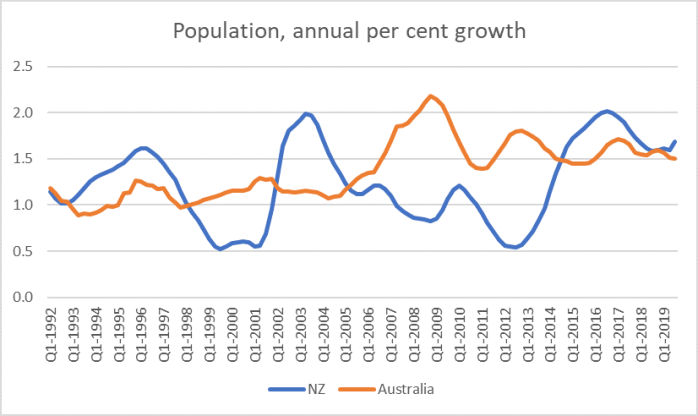

Between 2000 and 2018 our national population grew by 26 percent, but all of the above-average population growth has been from the Bay of Plenty northwards, with Auckland the fastest growing at 37 percent. Contrast that with population growth of 7 percent in Southland, 5 percent in Gisborne and 4 percent on the West Coast.

This population growth is despite the fact that Auckland’s GDP has grown at only 82 percent of the national average in the 2000 to 2018 period. In contrast, GDP growth was well above the national average in every region of the South Island, while Bay of Plenty and Northland had above-average growth too.

But there isn’t much sign that she or her department have thought hard about a compelling narrative that explains what has gone on. Instead we get this rather confused paragraph

Other cities and regions may have plenty of available land. However, they will need to improve their quality of business and quality of life attributes too if they are to significantly ease pressure in Auckland. And worldwide we see that agglomeration into major cities continues despite congestion and high property prices. Clearly, both employers and employees often see better long-term prospects in these major cities, despite efforts to develop other regions.

In both New Zealand and Australia, we certainly see more people in major cities, but little evidence of the vaunted productivity gains from continued concentration of people in these places. Natural-resource-based economies tend to be like that, but there is no hint of that as an issue in the Secretary’s story.

And from there the speech heads downhill again

Central government has created more capability through urban growth functions in HUD, and appointing senior regional officials to lead engagement and coordinate government across regions.

Of course lifting wellbeing across the regions is not just up to central government, which is why we see more partnering with local government and regional economic development agencies over recent years to develop action plans.

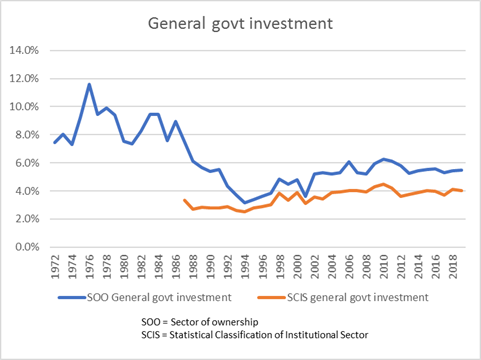

Lots of busy bureaucrats, lots of meetings for ministers and officials to open and attend, but not much sign of any understanding of quite why the overall economy has performed so poorly over so long (when almost all the tools of economic policy are controlled at the central government level).

Of the final page, I could commend her sense of humour, including this old Tom Scott cartoon (if memory serves from back in the late 80s or early 90s)

But then it is straight back to the self-congratulatory stuff

In closing, I want to acknowledge that being an economist working in public policy is incredibly rewarding, but it can also be challenging. We are a community of professionals that sometimes has to be loud to be heard. When people want the comfort of policy that is simple, certain, and swift, we can find ourselves the sometimes uncomfortable voice of technical rigour, nuance, and realism.

I guess that it might have been music to the ears of some in the audience. But we don’t – or shouldn’t – hire senior public servants to tell people (including ministers) what they want to hear. Sadly, there has been little consistent sign of The Treasury offering that “uncomfortable voice of technical rigour, nuance, and realism” in recent years, especially on these big-picture economic performance failings. They seem to have been content to just go along, to maintain access (perhaps) by not addressing the hard issues, and playing distraction with the fluffy stuff while the economic prospects – the living standards prospects – of New Zealanders, regional or urban, drifted further behind.

It is still early days for McLiesh. I have heard a few positive things about the new Secretary, including hints of renewed emphasis on rigour. I hope this particular speech isn’t a foretaste of the standard we can expect, but that the Treasury really does begin asking the hard questions, doing robust analysis, not simply going along with conventional political verities (eg regional development). Perhaps there isn’t a political demand for such advice and analysis – are there any politicians who really care? – but shouldn’t stop The Treasury being a voice, perhaps at times crying in the wilderness, pointing to how things might be such better here. As a hint, regional economic development agencies aren’t likely to be any substantive part of the answer.