I was going to attempt to articulate today where I agreed and disagreed with both the New Zealand Initiative’s Bryce Wilkinson and Social Credit on money, banking, fiscal policy etc (Social Credit having taken out a half page advert in Saturday’s Herald to attempt to rebut Bryce’s recent Herald op-ed, itself drawing on a longer recent Initiative publication). Perhaps tomorrow.

But in this morning’s papers I saw reference to a new plan (and/or critique of other plans) for policy in responding to the economic challenges of Covid, under the joint authorship of former Minister of Finance Roger Douglas and Auckland University economics professor Robert MacCulloch. MacCulloch kindly sent me a copy of the ten page underlying paper which goes under the title “In a New World, New Thinking is Required: Why Prioritization of Resources is Crucial to New Zealand’s Economic Recovery in the Wake of Covid-19”. MacCulloch’s Herald op-ed puts it more pointedly and succinctly under the headline “The time has come for trickle-up economics“.

Here is their Executive Summary

The Covid-19 outbreak has not only precipitated a health emergency, but also an economic crisis, unparalleled in modern history. For New Zealand to emerge from that crisis in a relatively healthy state, the Labour government will need to provide a clear framework for recovery, implementing policies which clearly prioritize those most affected by the societal and economic lockdown necessitated by the outbreak. To date, such prioritization has been lacking, with the Wage Subsidy Scheme unfairly advantaging big business and the professional elite, at the cost of money and resources which could have been better directed towards assisting the newly unemployed – namely workers, their families, and small business owners.

Ultimately, poorly targeted support in the form of helicopter payments, wage subsidies, or broad-based tax cuts (such as a moratorium on GST) is wasteful, and will only serve to entrench inequalities that existed prior to the pandemic. Equally, the time and costs inherent in planning large-scale new infrastructure projects – and the fact that they offer little practical help to the majority of workers who require help now – means that they should not be regarded as a panacea, aiding economic recovery.

Instead, clear, innovative policies, which not only prioritize those most in need, but which also lay the groundwork for further social and economic reform in the medium to long term, are required. For workers and their families, support can be offered via the mechanism of special risk accounts, tailored to meet their individual needs. For small business, help can be provided by facilitating conversations between businesses, landlords, and banks, as well as providing – upon the provision of an approved business plan – forgivable government loans.

Finally, to help manage the recovery, and ensure our younger generations are not saddled with debt, the government must also identify, and eliminate, unnecessary spending, privilege, and waste. It can find an extra $15 billion per annum by doing so, contributing to the recovery in the short term, and – more generally – to implementing wider scale reform once the immediate crisis has been put behind it.

It is an interesting argument. If it weren’t already a sadly-debased word, one might almost be tempted to label it “populist”. Douglas and MacCulloch don’t seem to have a problem with the idea of a wage subsidy scheme per se, but object to big businesses having claimed it.

Whilst the scheme, which already comes at a cost of $10 billion, has undoubtedly provided short term support to those who needed it – workers and small businesses – it has also been used to prop up corporate monoliths and institutions who should have been left to fend for themselves or – at the very least – should have received assistance in the form of a loan, instead of a handout.

But it isn’t clear why they think small businesses are worthy but big businesses (and the employees of the respective businesses) aren’t. Big businesses can often operate on very tight margins, and plenty of small businesses have had no special problems at all.

Personally, I’m not persuaded of the merits of how the wage subsidy was designed: as I’ve noted before the roots were in that perspective from months ago when the government thought the coronavirus issues were about China and the slow recovery of New Zealand exporters to China (including tourism). You had only to affirm that your revenues would be down 30 per cent in one month to get three months of wage subsidies, even though the “Level 4 lockdown” – the worst, government-imposed, period for many – was only about five weeks. But the large vs small company distinction simply doesn’t make a lot of sense to me, and (relative to need) there is no obvious reason why large companies should have more resources to tap than small companies.

My own unease about large companies is the special unit the government has set up in The Treasury to assist big companies. Since the initial Air New Zealand bailout not much has been heard of its activities, but the risk is that prominent, persuasive and well-connected big firms will end up much better treated than the small firms. Partly as a result, as far as possible, I favour one model for all. Done openly and transparently (there being all too little of that, not just around eg Cabinet papers and associated advice, but I think I saw an article recently noting that the deeds under which the Business Finance Guarantee Scheme are operating are also not being disclosed).

In many respects, however, the focus of the Douglas/MacCulloch paper is more forward looking from here.

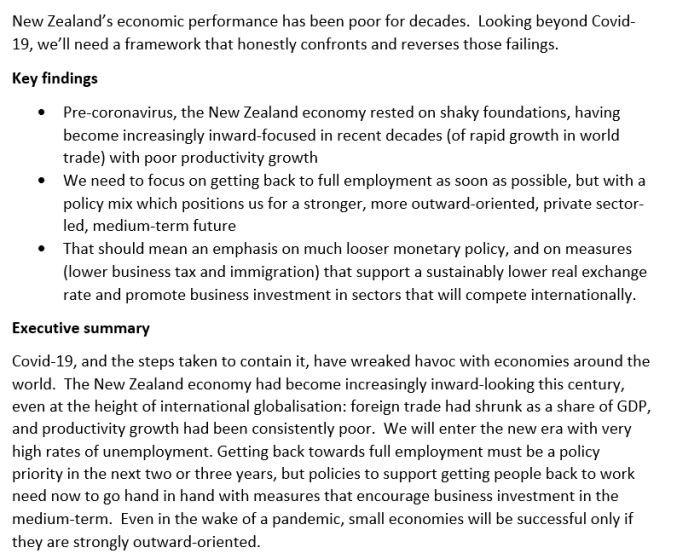

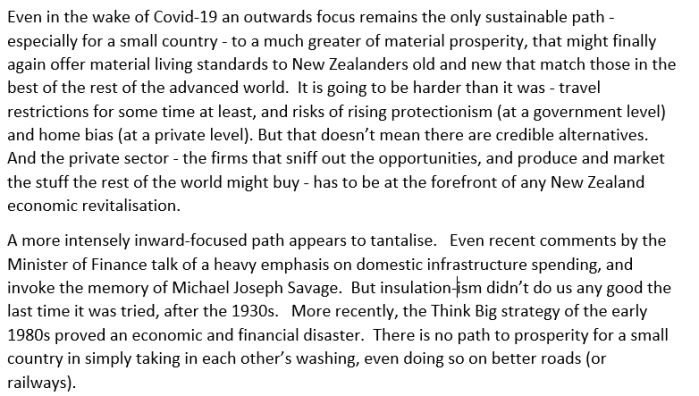

They start with a point on which I totally agree with them

To date, there has been little sense that the government has a cohesive economic plan to take us forward, either in terms of building the solid foundations required to help navigate our way out of the crisis (the short term response), or in terms of preparing the policies that will help New Zealand not simply recover, but stand stronger than ever (the medium to long term response).

They set out quite a lengthy list of “objectives for reform”, most of which I’d agree with, before moving on to some specifics, noting that

Right now, the protection of individual New Zealanders and their families must be the government’s number one priority.

They propose moving away from a model that has worked by funding employers to funding households/individuals directly

The mechanism for such support would be a special risk account, tailored to meet the specific needs of individuals and their families (if they have one). It would operate as follows:

• Step One: A company or employer makes it clear in writing that they cannot support an employee during the crisis or in its immediate aftermath.

• Step Two: The employee is either made redundant, or temporarily underemployed/unemployed, with the expectation that they will be re-employed once the crisis has passed and the business – inasmuch as it is possible – resumes its normal footing.

• Step Three: A special risk account is set up and documentation downloaded into that account for the employee to fill out. This documentation will help him/her identify any special support they require, including meeting mortgage or rent payments, as well as family, sickness, or any other (pre-qualified) payments.

• Step Four: Government provides payment (for a prescribed term and up to a specified limit) directly into the special risk account. If the account holder is already receiving unemployment support, which will be the case in many instances, then this payment will top up that support.

It does seem materially more resource-intensive than the wage subsidy scheme, so could not have been put in place at scale as quickly. I suppose it has the advantage of directly getting money in the hands of households, but then the established welfare system does that anyway (complete with supplements like the Accommodation Supplement).

The authors argue

By tailoring assistance to individual workers, the government can ensure that the support it provides meets specific needs, in a way that poorly targeted helicopter payments, subsidies provided to businesses, or even broad based tax cuts (such as a moratorium on GST) cannot. Not only that, such support also provides workers with a measure of respect, as well as a sense of autonomy and self-responsibility, that can only help to engender confidence, both at an individual and societal level.

There is something to the first sentence, relative (say) to those favouring lump sum handouts to everyone. On the other hand, some of the other ideas they seem to be pushing back against are more about demand stimulus in a recovery phase, rather than dealing with the direct income support issues.

The second section of the plan is about small business. It begins

Small businesses are the lifeblood of New Zealand’s economy. Sadly, not all of them are going to survive the health imperatives of the Covid-19 outbreak, which saw their closure. It is important, however, that as much as can be done, is done, to help viable businesses recover. In the short term at least, this will require other interested parties to step up, including banks and landlords, proffering help to small business owners by sharing their burden.

Not too sure about that “lifeblood” bit – there are lots of them but the smaller number of much larger businesses also employ a lot of people and are the vehicles through which much GDP is generated. But set that to one side now. What about those “banks and landlords”?

In such an environment, the hard-nosed approach adopted by some landlords is short-sighted. If a small business owner cannot meet the costs of a lease, and is forced to relinquish his/her business, then the property is likely to sit empty, with little prospect that it will be leased again in the short term. Much better – and more realistic – is the approach taken by groups like Westfield, who have signaled their intent to drop rents in their malls.

One might well agree with all that – and it would be consistent with an interesting post from Bob Jones a day or two back from his perspective as a large landlord – but it isn’t really clear what it has to do with the government. After all, tenants and landlords agree on how to allocate risk within their relationship, and they can also agree to vary those provisions, so what role for the government.

Similarly, the banks

Here, the banks have an important role to play, coming to the party by negotiating adjustments to mortgage payments that reflect the new economic realities of life, post-Covid.

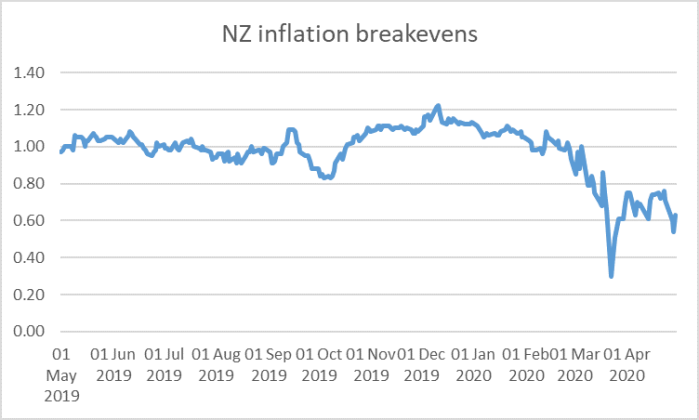

And, of course, banks have put in place residential mortgages “holidays” (delayed payments) and put a lot of commercial customers temporarily onto an interest-only basis. But again, if customers have taken a fixed interest rate that was an agreed commercial risk-sharing arrangement. And if they are on a variable rate, it might be better to look to our central bank, which sets the short-term interest rates that influence variable loan rates – and which, thus far, refuses to cut them any further come what may. Surprisingly, in a piece on macrostabilisation and recovery, monetary policy isn’t mentioned at all.

Douglas and MacCulloch go on

Of course, simply reducing rents, or even imposing a ‘rent holiday’ for a couple of months, will not be enough to save many businesses. It is here that the government has a role to play, supporting viable businesses in the form of forgivable loans.

And their plan?

The following, four-step strategy, is suggested as a way of supporting small businesses in trouble:

• If a business is unable to meet the costs required to open its doors again, or faces short-term difficulties, it will be required to meet with a business consultant, accountant, or government appointed consultant.

• As part of the consultation, it will be determined whether or not the business has a viable future. If a path forward can be found, then a business plan will be created.

• In the first instance, this plan will form part of any conversation that takes place between the business owner and his landlord, as a means of setting new, realistic rent payments that will help keep the business afloat. If necessary (and in the manner outlined above), the landlord’s bank should also be party to this conversation.

• Should rent mitigation not be enough, the business owner can also approach the government for a forgivable loan. An assessment will be made at this point about the viability of the business plan, and – if successful – a tailored loan will be provided to help the business recover.

It should be noted that the intent of this plan is not to provide loans to companies that have access to plenty of liquidity and other sources of capital. Rather, given the large sums that will inevitably be involved, the plan is for the benefit of those businesses that have been unduly affected by the lockdown and which need our support in the short-term.

It isn’t clear what the criteria would be for forgiveness? Presumably many businesses will end up defaulting anyway – as under the government’s IRD scheme for SMEs – but is the debt forgiven if your business survives or if it fails?

What is also striking – and this is a point I’ve made about many schemes – is that there are likely to be many businesses that, in principle, could be viable if we could simply wipe 2020 from the calendar and resume life in 12-18 months time. But in many cases it simply will not be worthwhile – the business will never generate enough – to justify taking on a lot more debt now.

The third strand of their plan is under the heading Infrastructure. They are sceptical of large-scale infrastructure projects

Put simply, large scale infrastructure projects are not only expensive, they take a long time to plan and implement; time we simply don’t have right now.

Mostly, as I’ve written elsewhere, I agree, although not always for their reasons (I rather doubt availability of labour is going to be a big constraint). They are keener on the housing side

If the government is to institute a big infrastructure push, then housing is perhaps the one area where this makes sense. It is an industry that employs a large number of people, and new housing stock can help resolve a long-standing social and economic problem confronted by many New Zealanders – the inability to afford their own home.

Perhaps, but as they surely know land prices – not houses – are the biggest obstacle. Not in the paper itself, but included in a Stuff article on the paper, Sir Roger is quoted thus

One area where there should be increased stimulatory spending is housing. In this area, Douglas described something like a supercharged KiwiBuild paired with planning reform and a shared-equity scheme.

Douglas said the key to getting housing right was “making a large quantity [of houses] available”.

The Government had to go into section development, while making sure land was released for building by reforming planning laws. There was plenty of land out there, but not enough capital to develop it.

Low-income people could be helped into housing through a shared-equity scheme, where the Government would take on part of their mortgage.

When asked how his state-backed building scheme would succeed where KiwiBuild failed, Douglas said it was a matter of getting the right people involved to notch up big productivity gains.

Among other issues one could raise, it isn’t fully clear to me how they can tell big business to look after themselves because there is plenty of capital available, while telling us the problem around housing is lack of capital to develop land. And I’m not sure the label KiwiBuild should really ever be used again for something an advocate wants taken seriously.

The penultimate section of the paper is headed “Where Will the Money Come From?”, which doesn’t really seem to distinguish between the large deficits that are more or less inevitable (even on their reckoning) right now, and the fiscal prospects in say five years time (which don’t look bad at present to me, especially given our low starting level of debt and low debt service costs). Anyway, their specifics are

It is also why we must look to eliminate privilege and waste, both of which have been part of New Zealand’s economy for too long. In total, there are $15-16 billion dollars of savings we might make per annum, simply by removing unnecessary government spending:

1. Ending Waste: By removing Kiwi Saver tax breaks and subsidies, by ending future government contributions to the New Zealand Super Fund, by retargeting income derived from those funds, and by reducing the excessive Votes available to government departments, we can quickly access approximately $9 billion per annum

2. Eliminating Privilege: Unnecessary privilege is entrenched in New Zealand society. By ending corporate grants and tax breaks, by stopping the Provincial Fund, by removing high income families (approximately 15% of the population) from access to Working for Families and Winter Energy subsidies, and by ending tertiary education grants for students other than those from low capital and low income families, we can make further savings around $7 billion per annum.

That is a bit of a mixed bag. They aren’t specific on the “corporate grants and tax breaks” they want to end, although if that includes film subsidies I’d certainly agree with them. But not all these savings are real savings, except within the current government accounting framework. I might (do) agree we shouldn’t be putting money into NZSF, but it is still government money – it is why when I talk about net debt I always use an NZSF-inclusive figure. Stopping contributions might free up some cash, but cash isn’t the real constraint here. Similarly, they might want to take NZSF earnings straight into the Budget, but it doesn’t change the substance – the earnings still improve the Crown’s position. I could happily sign up to a list of perhaps 20 government agencies to abolish entirely, but……sadly or otherwise, those aren’t where the big bucks are.

Douglas and MacCulloch end their paper with a section on “Building a Better Future”. Like me, they are energised by the continuing relative decline in New Zealand’s productivity performance (and, I think, fearful that things may only worsen relatively in a post-Covid world). Douglas and MacCulloch have written previous papers about far-reaching welfare reforms – I wrote (sceptically) about one such presentation here – and it is clear that that is still a focus now. They end this way

In an upcoming paper, the authors will examine in more detail what has gone wrong, why we should immediately set up working committees (SOE style) to make recommendations for the future, how we can free up an extra $20 billion via vastly improved productivity outcomes thanks to structural social welfare reform, and how we can use that money (along with the $15 billion previously freed up thanks to the elimination of waste and privilege) to institute innovative policies in areas as diverse as health, housing, education, welfare, personal tax, company tax, and superannuation.

Ultimately, we have a choice. We can either muddle through as we are – relying on policies that haven’t worked since the 1950s and which are ill-suited to our quickly changing world – or we can opt for a reset, introducing social and economic policies that will make New Zealand not only a richer but more equitable place to live; a country where every New Zealander has the chance to take control of their lives and secure a better future for themselves and their families.

It will be interesting to see their fuller plans. I wholly agree on the need for something quite different, although am more sceptical than they are that the welfare system as currently configured can explain any material amount of our continuing long-term relative economic decline.

I ended that earlier post this way

In many respects, the saddest line of the day was one made almost in passing by Professor MacCulloch. He told us that he administers a fairly generously-funded visiting professorship at the University of Auckland, which aims to bring in distinguished or innovative, leading international thinkers to contribute to policy debate and development in New Zealand. But the last three people who had been invited had declined the invitation to come. There was, so far as they could tell, nothing bold or interesting on the table here, no real prospect of significant reform, or interest in it from our political leaders.

Things were very different, in that regard, 20 or 30 years ago. It is not as if, sadly, we have in the interim solved all our problems, and re-establishing a position as a world-leading economy, or a world-leader in dealing with the various social dysfunctions. We just drift, and allow our elites to tell themselves (and us) tales about how everything is really just fine.

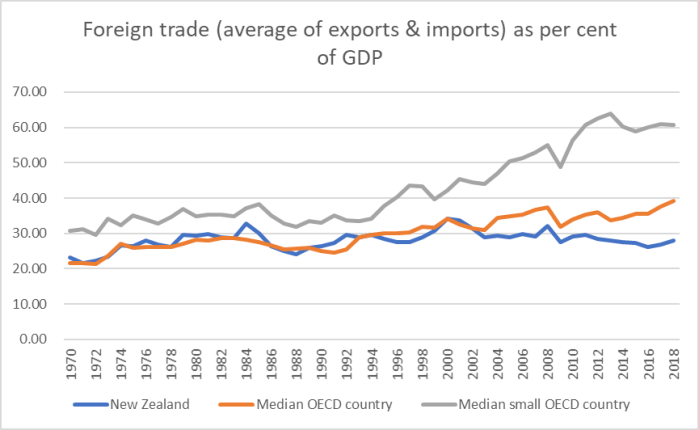

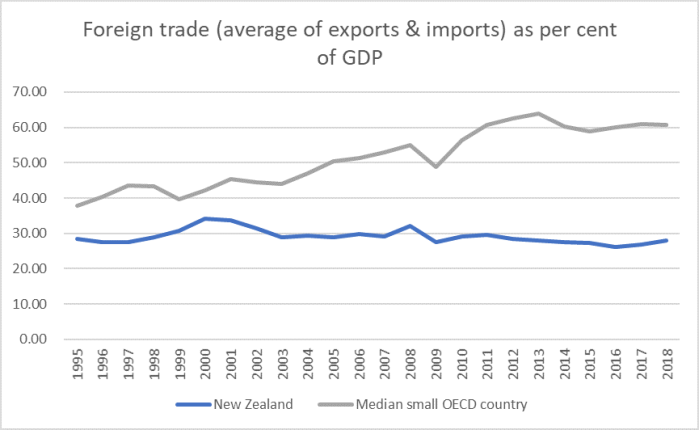

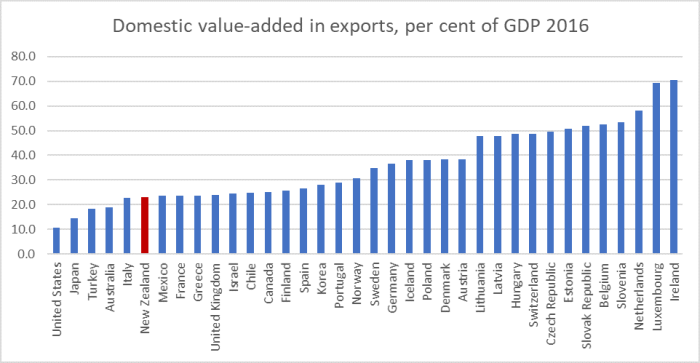

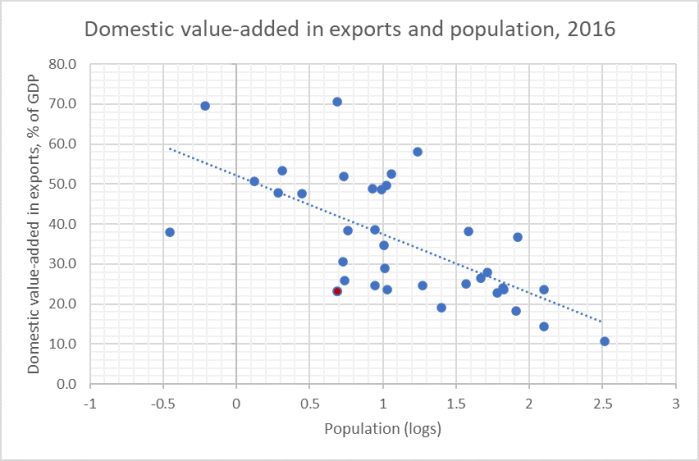

I guess at least we know things aren’t fine right now, but the contest ahead at present seems to be mostly between those who think New Zealand as it was last year is fine and those keen on building some version of new inward-focused Jerusalem that does not involve successfully earning our way in the world.

As for me, I still think some variant of my “national pandemic insurance” approach is the best – and most equitable – way to frame and think about immediate assistance, continue to think that monetary policy should have a key stabilisation, support and recovery role, and that we need to be looking outwards much more, with activity led from the private sector if we are (a) to get back to full employment as quickly as possible (not repeating the very slow post-2009 fall in unemployment) and (b) have some chance of finally building a more productive and prosperous New Zealand, reversing the gaps to much of the rest of the advanced world that have opened up and kept widening for decades now.