Last week the government announced the reopening applications for parent residence visas.

For a couple of decades, parent visas made up a pretty large chunk – around 10 per cent – of total residence visas issued. From 1997/98 to 2015/16, 75000 parent visas were issued. These were, almost certainly, all people who could not have obtained residence under the more-demanding skills-based segments of the immigration programme. Most probably, given the overall target/guidance for the number of residence approvals to be issued, issuing parent visas lowered the average quality of those given residence. Perhaps the effect wasn’t large – since the marginal approvals under the skilled streams often weren’t that skilled at all – but the direction of effect was pretty clear.

Parent visas weren’t the only such questionable streams, although it was the largest. Over the same period, for example, almost 20000 people got residence under “sibling and adult child” provisions.

All this in an immigration programme that was avowedly primarily about the potential economic gains to New Zealanders. Of course, the programme has never been all about economics – there are refugees for example, a strand almost entirely about humanitarianism – but the rhetoric of successive governments has been that the focus is economic benefit (and given how poor our productivity record, don’t we need better outcomes). And it has never been obvious how the parent visa (and related family strands) help on that count.

Late in their term, the previous government suspended the parent visa programme and MBIE data suggests there have been very few approvals since then. But no one had been sure what the future regime would be. Now we are.

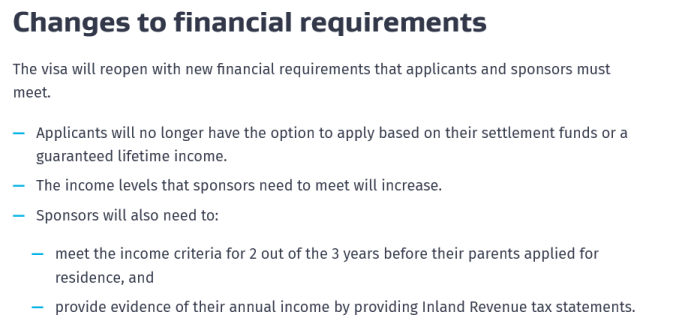

The positive aspect of the announcement last week is that there will only be 1000 places per annum. By contrast, under the previous rules often in excess of 4000 parent residence visas were being granted each year (although there is an uncapped – but more demanding – parent retirement residence visa on top of that).

Perhaps, then, one shouldn’t be unduly bothered about the new system. But if we are going to have an economics-focused immigration system, operating on a very scale by global standards, we should be aiming to get the very best from it. And it is hard to see how the parent visa policy fits that bill.

The fiscal dimensions of the equation are perhaps most obvious. Sure, these new parent visa residents won’t be eligible for New Zealand Superannuation straightaway. But the median age of people getting parent visas used to be about 60, and you only need to live here for 10 years to get full NZS. Average remaining life expectancy at age 60 in New Zealand is almost another 25 years. If these new residents work and pay income tax at all, very few are likely to even come close to making a fiscal contribution approximating the NZS cost. From some countries, any NZS entitlements have to be offset against pensions from home countries, but not all significant source countries have such systems. Perhaps as importantly, new residents are entitled to full access to the public health system. No doubt you have to pass a medical test to get your parent visa, but as for natives so for immigrants, health expenses tend to be materially higher in the last few years of life than in, say, your 20s or 30s. Health spending is a large and rising share of government spending and, over time, GDP. There are reasonable arguments – also open to some debate – that migration generally may be fiscally positive. For these elderly migrants it is almost inevitably not so.

The government doesn’t even try to pretend otherwise – although it certainly does nothing to highlight, or limit, the fiscal cost (eg greatly extending the residency requirement for full NZS). Instead, their argument for parent visas is a convoluted quasi-economic one. According to the Minister

As part of its work to ensure businesses can get the skilled workers they need, the Coalition Government is re-opening and re-setting the Parent Category visa programme, Immigration Minister Iain Lees-Galloway says.

The move will:

- support skilled migrants who help fill New Zealand’s skills gaps by providing a pathway for their parents to join them

- ….

- Help New Zealand businesses find the skilled labour they need

- Further strengthen the economy by helping businesses thrive.

You can probably ignore the pure spin in the last line (the economy not being strong, businesses as a whole not thriving, productivity growth being atrocious etc).

As for the rest, recall that the average skill level of the “skilled migrants” just isn’t very high at all (all those retail and cafe managers, aged care workers and so on). But also that the Minister and his department have never been able to produce remotely conclusive empirical evidence of the economic benefits of migration, and if we can only atract the people Lees-Galloway thinks “we need” by also taking on a big fiscal impost (see above) the gains must have been pretty thin and insubstantial to start with. Especially when every non-working migrant (ie probably most of the parent visa arrivals) will add to the demand for labour (derived demand from their consumption) without adding to the supply of it.

There has been some criticism that the new income threshold sponsors (the adult children) will have to meet mean that parent visas will be an option only for “the rich”. And there are some anomalies there, including the fact that a couple in which both are working part-time are treated much more onerously than a single fulltime income earner, but in the end if you are going to offer only a few places, they need to be rationed somehow, and given the likely financial cost to the taxpayer, it makes some sense to focus on the migrants who are actually earning a fair amount (although a household income of $159000 across two earners – while well above median – is hardly “rich). If there are any encouragement effects for really able younger migrants, they are going to be greatly attentuated if parent visas were handed out by lottery.

All that said, the new rules look rather weak, and look as though they will reward those who are prepared to game the system, pushing the boundaries (perhaps beyond breaking point)) and/or who have the capacity to rearrange their declared income across time. Work in a salaried position in a government department or big corporate and you probably have few options, but for others I’m sure smart accountants and lawyers will soon be advising on how to game the system. As you’ll see above, the sponsors do need a reasonably high income, but they only need it until the parent gets their visa, and then only for two of the three years previously. I guess that is supposed to allow for natural variability in eg business income, but it means you only have to find some way of inflating your declared income for a couple of years and your parent can get in, with no ongoing support or minimum income requirements.

I guess parent visas issue looks and feels a lot different to people (like me) whose parents and grandparents were all born in New Zealand than they do to people who’ve migrated, including to couples where a native New Zealander married someone abroad and settled here. I can even see how someone who migrated here at 25 when their parents were 45 might not have given much thought then to how a widowed parent abroad might cope at age 80. But the bit I really don’t get, at all, is why there should be any presumption that if you migrate to another country, leaving home and family, that should in short order (and you only need to have been resident here for three years to sponsor a parent) create some expectation that if aged parents have issues they should be able to come here, rather than that you return home. Migration – especially that to New Zealand (where the overall productivity gains are so questionable) – has always mostly benefited the migrant. We are doing them a favour much more than they, by coming, have done us a favour. But if you have family responsibilities at home, go back and meet them. Don’t expect the New Zealand taxpayer to support those who’ve never been a part of us, coming only at the end of life.

It would be different if any parent visas were provided only to those with guarantees of income and health support, and thus a rock-solid assurances that these individuals would not be a financial burden on the New Zealand taxpayer. I’d have no particular problem with an uncapped scheme of that sort – and the existing uncapped scheme doesn’t have those protections, especially as regards health spending. But it would require, say, evidence that an annuity had been purchased from a rock solid provider, and that rock-solid provision had been made for the purchase of lifelong comprehensive health insurance. The number of people who could meet that sort of standard would be really small (especially with real interest rates at record low levels). But in a sense that just demonstrates the difficulty of justifying parent visas on any reasonable economic test.

Perhaps there is a grounds for a weaker compassionate standard, but make that subject to a 20 year residence/citizenship test for the sponsoring child. But if you’ve been here for only three years, or haven’t bothered to become a citizen, if your parent needs you, go to them (we could even hold open the child’s residence visa for, say, five years while they did). I saw a a somewhat gung-ho columnist in the Dominion-Post on Saturday championing parent visas on the grounds that

Their children have become economically valuable New Zealanders. They deserve to have an avenue that responds to family need.

But in many cases (a) the children have not become New Zealanders, and (b) the evidence for the economic benefit to New Zealanders from migration is thin, at best. When and if, as a relatively new migrant, family needs you, go to them. They are your responsibility, not ours. It is a bit like the argument that it somehow isn’t fair that kids grow up without their grandparents – not only can grandparents visit relatively easily (in most cases), but surely you should have thought about that before leaving home and hearth, and grandparents, and settling in the most remote corner of the earth.

As I say, at 1000 visas a year this isn’t the biggest issue there is around temporary or permanent migration policy. But that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be scrutinised and challenged. If we are to be serious about lifting overal productivity, we need a hard-headed approach to policy, and one that prioritises the interests of New Zealanders.

(On another matter, I see that Stuff’s Kate MacNamara has returned to the fray with another column on the problem that is Adrian Orr. As I have to spend this afternoon in a meeting with the Deputy Governor and a Board member, I will save my comments on the article and the issues it raises until later.)

What does annoy me is that Permanent Residency Visas have the same rights and benefits as NZ citizens. Access to benefits like Universal Superannuation should not be given to Visa holders. There should be unique privileges reserved only to NZ citizens who are NZ tax residents.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Michael,

Thanks for your extensive analysis, as usual. I am one of these high skilled immigrants, directly affected by the parent visa category: need to reunite our family with my mother-in-law (my wife is her only child, her grandkids are in NZ, and she is pretty much alone overseas). Luckily our family fits the new requirements and we hope that we’ll get the visa once the category is re-opened in 2020.

However, I think you missed very important aspect in your analysis: those highly skilled immigrants like me have a choice of countries where they can live, and there is certainly competition between countries for such immigrants to some degree. Those immigrants who are denied to bring their parents may choose better avenues, such as moving to Australia or US. I found that immigration policies of both of these countries allow immigrants bringing their parents. I am sure some families will rather move overseas, than live with families split, being denied to bring their parents. These are families with one or both partners working in IT, or other high-skilled occupations…

That was a major issue for my family, as we very much love New Zealand, New Zealand became a new home for us, but the lack of parent visas until now meant we had no other choice but moving to Australia or US – just because we can re-unite the family in these countries, but not in NZ. I hope the new parent visa will work for us and we’ll be able to stay.

Best regards

Ivan

LikeLiked by 2 people

I have asked my highly skilled NZ born daughter to consider relocating to Australia formally by applying for Australian Permanent Visa and then to take up Australian citizenship. It is important to note that if you choose Australia, do not just decide to hop across to Australia. It is a Australian Special Visa Category for Kiwis that is a lifetime trap of 3rd class Australian Work Visa category. There is no path to true Australian permanent residency or Australian citizenship from the SVC.

As far as the issue of the Treaty of Waitangi is concerned it is actually a racist social welfare policy favoring only one race ie Maori. We will see increasing demands from Maori that the entire country belongs to Maori and that everyone else are migrants. The Maori demands from Fletcher Building at Ihumatao is a direct threat to all private owners that Maori wants to dispute all future ownership of land, sea and air throughout NZ.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment Ivan. I guess in a sense your comment makes the point I was alluding to in the post: is our wider migration programme bringing econ benefits to NZers (no matter how decent and hardworking the individuals etc). If not, it is a bit like film subsidies – we have to have them, we are told, as everyone else does, without stopping to ask whether we benefit at all.

I can understand the challenge for individual families, but of course policy parameters need to be set on a wider NZ public interest basis. I’d probably have fewer objections if we had a much lower overall immigration target, really only getting – refugess aside – a few thousands really able people (probably the most an underperforming country like NZ can really hope for).

But in the end the economic question is whether the wider programme is benefiting NZers. If so, the evidence has proved very hard to find.

LikeLike

The downside

“An ‘elderly’ person in NZ illegally racked up a medical bill of more than $165,000 that was later written off by a DHB. Northland DHB recently wrote off about $335,000 as bad debt, the majority of which was owed by the one elderly patient.

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12275579

According to the news this morning the person concerned will be allowed to stay in NZ. What will their future costs be

LikeLike

When your grand-ancestors moved here, would they have been prohibited from bringing their parents over to join them after they had established themselves?

LikeLike

No (not that any did) but had they done so they’d not have been eligible for the equivalent of NZS (age pension didn’t come until 1898, with demanding residence and income tests) or healthcare (what little was available at all, state or private, in the 19th C. ( Of course, in 19th C most migrants to the New World did so never expecting to see parents again.)

In a sense, that is the modern equivalent of my suggested std at least for parents of fairly recent arrivals: provide concrete assurance you won’t be a fiscal burden and you can come. If not, then no – your kids can always come back to you.

LikeLike

Ideally, I’d prefer to have better bilateral agreements among countries with comparable systems allowing for better entitlement portability or recognition.

For example, if about as many Canadians moved to NZ for retirement as the other way round, and the public health care systems in the two countries were comparable, then we just shouldn’t worry about whether a Canadian moves here and imposes cost on the NZ public health system – there’s a Kiwi doing the same over in Canada and they offset each other.

If the bilateral flows got out of whack, then you could have a fiscal transfer arrangement where the country with more outbound migration pays the other country an amount equivalent to the expected annual healthcare cost of people from that cohort who’d left.

I don’t think there’s anything in-principle hard about doing something similar for pension portability; there’s already a bilateral treaty on it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

In principle, something like that could work for NZ and Canada and perhaps the UK. Less clear how easily it generalises (without knowing more about how the respective health systems work) – incl how it works with Aus, where the main flow tends to be one way (probably even at older ages?)

LikeLike

How long have you been in NZ ?

That’s exactly what happened with Australia. It got out of whack. John Howard asked Helen Clark for a contribution. She said no. Howard immediately changed the rules and turned down the welfare, health and education spigots

LikeLiked by 2 people

Isn’t all this just dancing on pin heads. As you have previously pointed out its the quantum that is the problem. The criteria is a set of proxies for some value judgements politicians want to impose. A paper scoring system Like we have is riddled with problems more fundamental than whether a qualification equals a real world skill. The random ballot employed in the nineties would elicit equal results.

With the world passing a sustainable population level in 2011 we need to reset our immigration policy before we do more damage to our economy and way of life.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Largely agree, but it would be different matter if somehow we were attracting 45000 pa truly exceptional people. Not likely, in the slightest, but my framework is more empirical than in-principle (I can envisage a world – unlikely as it is – in which large scale migration could benefit NZers economically).

LikeLike

No point bringing in 45,000 truly exceptional people to NZ. They will just end up being unemployed Uber drivers. We do not have the industries to ensure that their skills are readily used. Our top industries employment opportunities are cleaning cow dung after the milking machines, picking fruit before they rot for our farms, picking up coca cola bottles off our beaches for tourists and wiping up poop from the carpets of health care facilities. Jobs our highly University skilled NZ kiwiborn would not do anyway.

LikeLike

There are no proxies for ‘truely exceptional people’, you have one view, Labour another, Greens another. Most NZer’s want a ‘replacement’ to the emigrant we just lost, in other words ‘someone like themselves’.

Fools errand.

In your day the Reserve Bank was firm of the view that migrants added no or minimal economic benefit [.05%].

LikeLike

now we really are dancing on the head of a pin. in econ terms, I’d say there are “truly exceptional people”, but they are all but impossible to identify ex ante. I guess I just want to keep the hypothetical option open as I engage with people who are strongly pro-immigration in principle, so I tend to focus on whether our policies (or feasible variants) of large scale immigration are actually generating productivity gains.

Re the RB, of course is fair to note that the Bank has always (appropriately) had a cyclical (and short/medium term) perspective rather than a long-term one, and neither immigration nor long-term econ performance were really their/our field.

LikeLike

I agree with you that parents (and other relatives) should be let in and that 1,000 is not many. Judging by the response of many on the Interest.co.nz Blog there are many New Zealanders who are troubled by this issue. It should be fairly easy to guarantee that on average such immigrants do not cost NZ tax-payers (purchased pensions and health care). The current system will be gamed. Talented tech experts will arrive; bring parents; leave parent here while they take their tech experience to Australia or America where it is better paid. Meanwhile their parents will be left in NZ, a low crime society with little serious racial tension (I am writing this in Northern France where squads of heavily armed police patrol public areas that are protected by ugly concrete blocks). Our govt underestimates NZ’s non-financial attractions and over-estimates its financial ones. A simple commitment to the principal that all immigrants (on average) are proven to benefit NZ tax-payers would help reduce the racial tensions may occur if we have a recession.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember when my late great aunt moved here from England about 15 years ago – both her daughters lived in NZ (skilled migrants from England and Zimbabwe) and she had no close family in Blighty, and her only sister in NZ. She ended up delaying moving here by 5 years as the government increased the money she had to bring to cover her healthcare costs. Somehow she managed to stump up the extra cash and made it here, only to die 2 years later. To my younger self it seemed unjust that she’d managed to scrape together the requisite cash only to have the goalposts shifted at the last minute.

My older self only wishes the levels were set at the right level (whatever that is) and kept relatively stable so people can make plans. Like super plans, shifting the goalposts in a game of political football is neither fair nor productive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My commitment to a principle that average immigrants are proven to benefit NZ still makes sense – it allows even the unfortunate immigrant who is down on his/her luck to defend their acceptance by INZ and it cuts the ground from under the feet of racist critics of immigration.

There are exceptions – we have to assume that NZ immigrants in the partner of a NZ citizen category are benefiting NZ via their influence on their partner but the big exception is the refugee quota. Only recently I read a journalist saying “it is proven that refugees are net contributors to a country” – that may be true for other countries but NZ claims and ought to be taking the most unfortunate refugees from UNHCR camps – not the doctors and engineers but those with medical conditions that cannot be treated in a camp (for example no facility to keep insulin cold for diabetics). The typical refugee to NZ costs us about $100,000 and I’m pleased my taxes contribute to saving lives. Obviously we should be recording costs and successes at integrating into NZ but if it is profitable then something is wrong.

LikeLike

I had to leave home and a job in a bank to go to university in Hobart.

I then had to leave Tasmania to find decent work as an economist.

If you migrate to another country, you leave more than a few things behind that are important to you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Grown up people who can’t bear parting from their parents should not emigrate to another country.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it has more to do with 2 old parents who now are far to old to care for themselves and kids who have to work to feed their own families in NZ. It is more a humane difficult decision between leaving parents to rot in poverty thousands of miles away or grown children to return to poverty to rot with parents can be a really difficult dilemma.

LikeLike

That is clearly an incorrect characterisation. The median age of parent visa recipients is 60 not 85.

When you say “rot in poverty”, where did you have in mind? The UK,, eg, has higher per capita GDP. And the PRC is a middle income country now. And any person good enough to be a skilled migrant here, should be able to earn a reasonable income in their home labour market (given that we don’t get many skilled migrants from, eg, Somalia).

LikeLike

What practical difference is there for most migrants between PR and NZ citizenship? Anecdotally it doesn’t seem to be especially worthwhile to take the extra step towards citizenship?

LikeLiked by 1 person

If the parents coming over help out their grown children with grandkids to the extent they don’t have to cut back work as much, these parents (who are doing jobs worth a minimum of 80k, or 100k for two parents) will end up making a significant economic contribution.

LikeLike

Childminding services are not particularly highly valued/prices in the market.

LikeLike

Misdirection. The narrative is usually presented in such a way the reader is led to the assumption it is talking about 2 parents. In fact there are 4 parents. If you accept the 2 parent case then you have to accept the 4 parent case

The daisy chain in operation – how 2 can become 14 or 28

A 25 yo migrant couple can become permanent residents who can then bring in both sets of parents. That’s 4 parents. Once the 4 parents are in, and obtain permanent residency they in turn are the children of 8 parents who theoretically can then be brought in. Thus the 8 grandparents of the initial couple can indeed be brought in.

Add in 2 siblings for each of the two original plus their 2 spouses and repeat, the number doubles again

Not new

https://www.interest.co.nz/property/79849/barfoot-thompsons-median-price-took-big-drop-january-sales-volumes-were-strong#comment-841170

LikeLike