Not many things bother me (get inside me and really churn me up) that much. But an email yesterday did, and in truth still is. It demanded $1000 of so in Bitcoin within 48 hours or our “secret” would be revealed, in lurid video detail, to everyone (all contacts from all media, all accounts), sent from our very own family email account. Our “secret” apparently was some pretty sick pornography that we had allegedly been watching, and had (so it claimed) been recorded watching. When I consulted some tech people the advice was that it was (probably) pure scam – demanding money with menace, but with nothing actually (creatively concocted of course) to back it up. I certainly hope so, but in the unlikely event that people receive such icky emails tomorrow……..well, there are some sick people, capable of evil acts, out there. Some “speech” should be illegal, and is – not that I expect the Police to be able to do anything about this extortion attempt. (Meanwhile, the economist in me couldn’t help reflecting on the pricing strategy – surely almost anyone who actually had this stuff to hide would be willing to pay a lot more than $1000 to prevent exposure?)

Today I wanted to write about a short piece the New Zealand Initiative published 10 days or so ago as a contribution to the debate around the proposals the government is considering for reform of the governance of our schools. Their short research note got a lot of media coverage, although to me it posed more questions than it really answered, and I wasn’t entirely sure why the reported results had any particular implications for how best to govern (state) schools. I’d had the report sitting on my pile of possible things to write about for a few days, but I noticed yesterday that the Initiative’s chief economist, Eric Crampton, had devoted a blog post to the report (mostly pushing back against some criticisms from Brian Easton). That post provided a bit more detail.

I’m not heavily invested in the debate about school governance. As I noted to one reader who encouraged me to write about it directly, my kids are now far enough through the system that whatever changes the government finally makes and implements aren’t likely to materially worsen the education system for them. And if I’ve found little to praise in the schools we’ve had kids at (one has been mediocre – on good days – since friends were first “forced” to send their kids there 30+ years ago), nothing persuades me that more centralised control would be for the good (of kids, and of society, as distinct from the officials and politicians who might get to exercise more power). And my predisposition is to be suspicious of anything Bali Haque is involved in, and that predisposition was provided with some considerable support when I read a commentary on the report of the Tomorrow’s Schools Taskforce, by the economist (with long experience in matters around education policy) Gary Hawke.

But I was still left not entirely persuaded that what the Initiative had published really shed much light where they claimed it did. Perhaps things will be clearer when the fuller results are published later in the year, but for now we can only work with what we have.

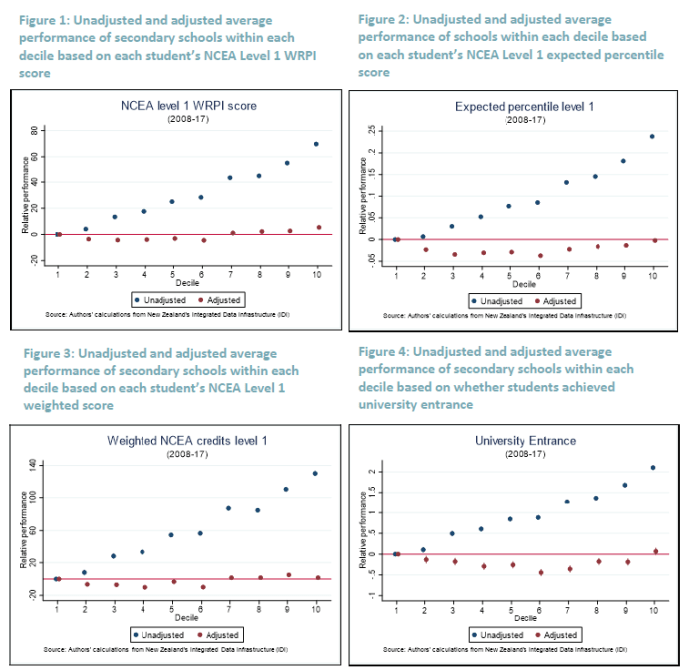

The centrepiece of the Initiative’s research note is this set of charts

They’ve taken various measures of NCEA academic outcomes (one per chart) and shown how school outcomes vary by decile with (red dots) and without (blue dots) correction for the “family background” of the student. “Family background” is the fruit of the highly-intrusive Statistics New Zealand Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) – which researchers love, but citizens should be very wary of – and in Eric Crampton’s less formal note this quote captured what they got

For the population of students who completed NCEA from 2008 through 2017, there’s a link through to their parents. From their parents, to their parents’ income. And their education. And their benefit histories. And criminal and prison records. And Child, Youth, and Family notifications. And a pile more. Everything we could think of that might mean one school has a tougher job than another, we threw all of that over onto the right hand side of the regressions.

The results are interesting, of course. They summarise the result this way

But this does seem to be something of a straw man. Should we be surprised that kids from tough family backgrounds achieve worse academic results than those that have more favourable family backgrounds? I doubt anyone is. And I have no problem with the idea that a decile 1 school might do as good a job “adding value” as a decile 10 school, but these charts don’t show what I would have thought would be the rather more interesting difference (at least if governance is in focus): what is the range of outcomes within each decile. Quite probably there are excellent decile 6 schools and really rather poor ones, and which school fits which category is likely to change over time (leaders and leadership make a difference).

Take, for example, the school my son now attends, and where I also had the last couple of years of my schooling. 60 years ago it was mediocre at best, then a long-serving headmaster dramatically lifted the performance on a sustained basis, only for the school under yet new leadership to slip back so badly that when our son was born we were contemplating exceedingly-expensive private school options (an option for us, but not for many). Fortunately, there has been another revitalisation over the last decade and my impression now is that the school does as well as any in adding value. But, as far I can see, what was reported so far of the Initiative’s work sheds no light on this divergences within deciles at all. And yet surely questions of governance are at least potentially relevant here: could a plausible and credible different governance model have prevented some of that across-time variance in outcomes for Rongotai College? If it could have, it would surely have to be seriously considered.

Having noted that it is hardly surprising that kids from homes with more favourable factors emerge from school with better results than those from less favourable backgrounds, I was intrigued by just how flat those red dots are across deciles in each of the charts above. The message was simple – adjust for family background and there is no systematic difference across school deciles in the average academic results the students achieve. And yet, doesn’t the government put in much more money (per student) to low decile schools than to high decile schools? Is it all for naught? It would be uncomfortable if true, but that is what the results appear to say. Perhaps in the end the answer is that the funding differences, although appearing large when translated to the “donations” higher decile schools expect, really aren’t that large (or large enough?) after all? Perhaps there is something in the possibility that lower-decile schools struggle to get enough capable parents in governance roles (I know both my father and my father-in-law, both Baptist pastors, ended up serving as coopted board of trustee members in low decile schools) or even to attract the best teachers. Whatever the answer, I hope the Initiative looks into the question as they write about their fuller results.

The other question I was left wondering about was whether what the New Zealand Initiative has produced is really adding much value over and above the less-intrusive, more rough and ready, approaches to assessing school quality that people have used for years. Here, I don’t mean that straw man suggestion that people think higher decile schools are better academically – perhaps there are a few who believe that, but I doubt they are many. My approach to schools for years has been to take the NCEA results, and compare how an individual school has done relative to others (total, and distinguished by sex) of the same decile. Plot all the schools in Wellington, and I could get a reasonable sense of which had students achieving better results than one might have expected for their decile. Add in things like ERO reports, and talking to people who’ve had personal exposure to a school, and one gets quite a bit of information. And people will, rightly and reasonably, want to consider things other than just academic value-added in making the (rather limited) choices they have about schooling for their children (be it sports, arts, behavioural standards, uniform, single-sex vs coed, ethos or whatever).

In the end, however, my biggest concern remains the IDI itself. It is curious to see the New Zealand Initiative championing its use in evaluating schools (and they are researchers, and researchers are drawn to data as bees to honey) when the Initiative has historically tended to emphasise the merits of genuine school choice. It is something I strongly agree with them on. But decentralised markets, with parents deploying purchasing power, wouldn’t have (at least naturally) the sort of highly-intrusive joined up information that IDI provides.

And nor should government-provided school systems. I’m not sure how Statistics New Zealand matches my son, enrolled at a local school where we provide only our names, phone numbers, and street addresses, to the education levels of my wife and I, let alone our marital status, (non-existent) benefit histories or criminal records or the like. It is none of the school’s business, and it is none of the government’s business. As citizens, we should be free to keep bits of our lives compartmentalised, even if all this joined-up data might be a blessing to researchers.

I touched on some of these issues in a post late last year.

Statistics New Zealand sings the praises of the IDI (as does Treasury – and any other agency that uses the database). I gather it is regarded as world-leading, offering more linked data than is available in most (or all) other advanced democracies – and that that is regarded as a plus. SNZ (and Treasury) make much of the anonymised nature of the data, and here I take them at their word. A Treasury researcher (say) cannot use the database to piece together the life of some named individual (and nor would I imagine Treasury would want to). The system protections seem to be quite robust – some argue too much so – and if I don’t have much confidence in Statistics New Zealand generally (people who can’t even conduct the latest Census competently), this isn’t one of the areas I have concerns about at present.

But who really wants government agencies to have all this data about them, and for them to be able link it all up? Perhaps privacy doesn’t count as a value in the Treasury/government Living Standards Framework, but while I don’t mind providing a limited amount of data to the local school when I enrol my child (although even they seem to collect more than they need) but I don’t see why anyone should be free to connect that up to my use of the Auckland City Mission (nil), my parking ticket from the Dunedin City Council (one), or (say) my tiny handful of lifetime claims on ACC. And I have those objections even if no individual bureaucrat can get to the full details of the Michael Reddell story.

The IDI would not be feasible, at least on anything like its current scale, if the role of central government in our lives were smaller. Thus, the database doesn’t have life insurance data (private), but it does have ACC data. It has data on schooling, and medical conditions, but not on (say) food purchases, since supermarkets aren’t a government agency. I’m not opposed to ACC, or even to state schools (although I would favour full effective choice), but just because in some sense there is a common ultimate “owner”, the state, is no reason to allow this sort of extensive data-sharing and data-linking (even when, for research purposes, the resulting data are anonymised). There is a mentality being created in which our lives (and the information about our lives) is not our own, and can’t even be stored in carefully segregated silos, but is the joined-up property of the state (and enthusiastic, often idealistic, researchers working for it). We see it even in things like the Census where we are now required by law to tell the state if we have trouble “washing all over or dressing” or, in the General Social Survey, whether we take reusable bags with us when we go shopping. And the whole point of the IDI is that it allows all this information to be joined up and used by governments – they would argue “for us”, but governments’ view of what is in our good and our own are not necessarily or inevitably well-aligned.

In truth my unease is less about where the project has got to so far, but as to the future possibilities it opens up. What can be done is likely, eventually, to be done. As I noted, Auckland City Mission is providing detailed data for the IDI. We had a controversy a couple of years ago in which the then government was putting pressure on NGOs (receiving government funding) to provide detailed personal data on those they were helping – data which, in time, would presumably have found its way into the IDI. There was a strong pushback then, but it is not hard to imagine the bureaucrats getting their way in a few years’ time. After all, evaluation is (in many respects rightly) an important element in what governments are looking for when public money is being spent.

Precisely because the data are anonymised at present, to the extent that policy is based on IDI research results it reflects analysis of population groups (rather than specific individuals). But that analysis can get quite fine-grained, in ways that represent a double-edged sword: opening the way to more effective targeting, and yet opening the way to more effective targeting. The repetition is deliberate: governments won’t (and don’t) always target for the good. It can be a tool for facilitation, and a tool for control, and there doesn’t seem to be much serious discussion about the risks, amid the breathless enunciation of the opportunities.

Where, after all, will it end? If NGO data can be acquired, semi-voluntarily or by standover tactics (your data or no contract), perhaps it is only a matter of time before the pressure mounts to use statutory powers to compel the inclusion of private sector data? Surely the public health zealots would love to be able to get individualised data on supermarket purchases (eg New World Club Card data), others might want Kiwisaver data, Netflix (or similar) viewing data, library borrowing (and overdue) data, or domestic air travel data, (or road travel data, if and when automated tolling systems are implemented), CCTV camera footage, or even banking data. All with (initial) promises of anonymisation – and public benefit – of course. And all, no doubt, with individually plausible cases about the real “public” benefits that might flow from having such data. And supported by a “those who’ve done nothing wrong, have nothing to fear” mantra.

After all, here the Treasury author’s concluding vision

Innovative use of a combination of survey and administrative data in the IDI will be a critical contributor to realising the current Government’s wellbeing vision, and to successfully applying the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework to practical investment decisions. Vive la révolution!

Count me rather more nervous and sceptical. Our lives aren’t, or shouldn’t be, data for government researchers, instruments on which officials – often with the best of intentions – can play.

And all this is before one starts to worry about the potential for convergence with the sort of “social credit” monitoring and control system being rolled out in the People’s Republic of China. Defenders of the PRC system sometimes argue – probably sometimes even with a straight face – that the broad direction of their system isn’t so different from where the West is heading (credit scores, travel watchlists and so). That is still, mostly, rubbish, but the bigger question is whether our societies will be able to (or will even choose to) resist the same trends. The technological challenge was about collecting and linking all this data, and in principle that isn’t a great deal different whether at SNZ or party-central in Beijing. The difference – and it is a really important difference – is what is done with the data, but there is a relentless logic that will push erstwhile free societies in a similar direction – if perhaps less overtly – to China. When something can be done, it will be hard to resist eventually being done. And how will people compellingly object when it is shown – by robust research – that those households who feed their kids Cocopops and let them watch two hours of daytime TV, while never ever recycling do all sort of (government defined – perhaps even real) harm, and thus specialist targeted compulsory state interventions are made, for their sake, for the sake of the kids, and the sake of the nation?

Not everything that can be done ends up being done. But it is hard to maintain those boundaries, and doing so requires hard conversation, solid shared values etc, not just breathless enthusiasm for the merits of more and more linked data.

As I said earlier in the post, I’m torn. There is some genuinely useful research emerging, which probably poses no threat to anyone individually, or freedom more generally. And those of you who are Facebook users might tell me you have already given away all this data (for joining up) anyway – which, even if true, should be little comfort if we think about the potential uses and abuses down the track. Others might reasonably note that in old traditional societies (peasant villages) there was little effective privacy anyway – which might be true, but at least those to whom your life was pretty much an open book were those who shared your experience and destiny (those who lived in the same village). But when powerful and distant governments get hold of so much data, and can link it up so readily, I’m more uneasy than many researchers (government or private, whose interests are well-aligned with citizens) about the possibilities and risks it opens up.

So while Treasury is cheering the “revolution” on, I hope somewhere people are thinking harder about where all this risks taking us and our societies.

Some thoughts anyway. Not all that can be done should be done, and the advance of technology (itself largely value-neutral) opens up many more things that can be done that shouldn’t be done.

Most interesting has given me a lot to think about.

LikeLike

Two points:

The only response to scam emails is ‘publish and be damned’. Blackmailers, if they really do have incriminating information, will only come back for more.

Your comments regarding the proposed changes in the structure of education are sensible however there might be an argument for centralising non-academic functions in schools such as purchasing, facilities maintenance, and assistance with recruiting. These are areas of expertise that are not part of the normal school principle’s background.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, i largely agree re support functions.

LikeLike

Unfortunately we have new generations coming through that have already decided that their privacy is not worth protecting. It has been traded for easy access to social media, starting at an age where it was not something you thought much about.

Now it is just part of their lives, giving access to their private information is normal. I can but hope that in the decades to come this is looked back as an oddity in our history. However it is more likely that we will never regain control and will be misused in the future. The comparison with the Chinese system is the more likely outcome. Done in the name of good, but in reality forcing us into a straitjacket of behaviour and social engineering.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This short report is just a first step. I agree that this shows now what many have suspected. And yet the Haque report recommended a complete overhaul of school governance arrangements based on a water-flows-uphill hypothesis. It’s why we brought this bit of the analysis forward.

We also have results on the distribution of strong and weak performance, measured overall, then sorted by decile. There are a lot of overlooked strong performers in low decile schools, and hidden weak performers in the high deciles. Being able to point to these schools would let the Ministry try to figure out which bits of practice have led to those outcomes – we can’t identify practice as that isn’t in IDI.

Future work will restrict the sample to kids whose background characteristics predict poor performance, so we’d then be able to see whether schools that perform well overall are also the ones best able to help those kids, or if there are schools that are specifically good in that role. And, again, that could help the Ministry to see where they need to go and figure out what’s going right so that better practice can be shared.

And there’s rather more to come after that.

LikeLike

Those scam emails have been circulating for several months. I have received several, with no consequences (of course) when I ignored them. I have not kept any of them, so I can’t check how much they were demanding; it might be interesting to see if the scammers are trying various prices to see what yields the best return.

LikeLike

The UK just jailed a cyber extortionist who had been a prolific pest for about 5 years and pocketing millions, mostly in small sums from victims. See more on BBC.

LikeLike

Have a look at the Australian Statistics Office, and the work they’re doing around collection of household expenditure data.

Unless we’re careful, the statisticians will build a prison – albeit with the very best of intentions.

LikeLike