On Friday afternoon an email turned up from the Reserve Bank of Australia with this simple message

Draft copies of papers presented at the Reserve Bank of Australia 2019 Conference – Low Wage Growth – held from 4 to 5 April 2019 have been published on the Bank’s website.

That looked interesting, so I clicked on the link to the papers and found that the very first one was by a Reserve Bank of New Zealand author – not just a junior researcher, but someone who is now manager of their (economic) modelling team. The paper had the title “New Zealand wage inflation post-crisis” which, of course, immediately grabbed my attention. I’ve written quite a bit here about wages in New Zealand, including (in recent months) here and here. My take has been that, if anything, wage growth in New Zealand has been surprisingly strong, given the weakness of productivity growth (most especially in the last five or six years).

There is some interesting material in the Reserve Bank paper, including the use of the highly-disaggregated data available from Statistics New Zealand’s IDI and LBD databases (my reservations of principle about them are here). For example, the author looks at the possible contribution of industry concentration. In the US context,

Recent commentary has highlighted the role that industry competition may play in suppressing wage inflation. The hypothesis is that firms in very concentrated industries can act as a monopsony buyer of labour, and therefore suppress wage inflation through their market power.

But

First of all, industry concentration has actually decreased in New Zealand over the past two decades (figure 11). This is in contrast to developments in the United States.

That apparent reduction in concentration surprised me a little, but it isn’t my area at all. The author goes on to note

To account for the potential for different characteristics of workers in different industries, we have matched workers in high and low concentration industries across a range of other characteristics. Figure 12 presents the wage growth differential for matched individuals in the 2011 cohort. The figure shows that, when accounting for the different characteristics of employees across industries, those in concentrated industries tend to see slightly higher wage growth than those in more competitive industries.

Interesting, but (as they note) experimental.

But right through even that discussion, the author starts from the presumption that there is a puzzle to explain, in the form of low wage inflation.

As a reminder, this chart shows cumulative increases in New Zealand wage rates relative to cumulative growth in nominal GDP per hour worked. A rising line suggests that, on this measure, wage rate increased faster than (loosely) the earnings capacity of the economy.

(Nominal) wages have been rising faster than (nominal) productivity, and there is no very obvious difference between the trend in the years running up to the 2008/09 recession and those since.

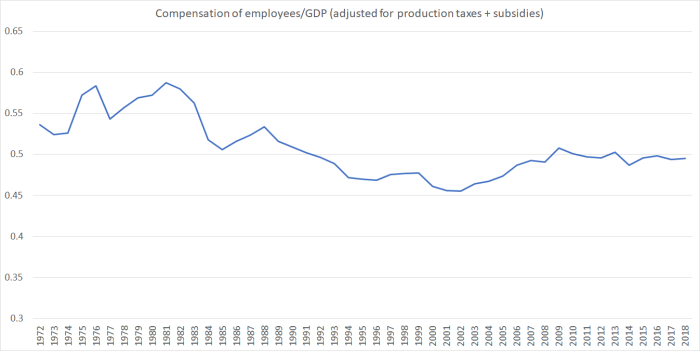

Not inconsistent with that is the labour share of total GDP, which has held up considerably more here (in the last 20 or 30 years) than in many other advanced countries.

But not a shred of this appears in the Reserve Bank’s conference paper. In fact, the thrust of the paper is such that it appears that they mostly see wage inflation and CPI inflation as the same thing, and so the paper falls back on the lines they’ve been trying to run for years as to why inflation has been so low (hint: because monetary policy was, on average, a bit tight).

This is from the Abstract

Nominal wage and consumer price inflation have been subdued in New Zealand post crisis, particularly since 2012. This paper discusses a number of candidate explanations for these muted nominal wage inflation outcomes. The most notable explanations include: a gradual absorption of spare capacity amongst New Zealand’s major trading partners; sharp declines in oil and export commodity prices in 2014/15; a significant rise in labour supply, and less inflationary pressure stemming from migration; and a change in price setting behaviour, with inflation expectations becoming more adaptive.

Basically, despite the title, it isn’t a paper about wage inflation – which would surely focus substantially on what happened to wages given all else that had gone on in the economy – at all.

Consistent with this interpretation, I searched the document, and the word “productivity” did not appear at all, and yet in almost any possible story about longer-term wage growth, labour productivity should be one key consideration. The author shows various charts of elements of the Bank’s forecasts they got wrong over the last decade, but again the productivity forecasts don’t appear. Government agencies (Reserve Bank and Treasury) have done consistently badly on that score.

Carrying on with the search function, “terms of trade” didn’t appear in the paper, and nor did “investment”.

At the Governor’s speech a couple of weeks ago, a retired academic in the audience asked the Governor how the Bank was going to get away from what he (the academic) characterised as past Reserve Bank tendencies to treat wage inflation as basically the same thing as general inflation and, therefore, something to be jumped on. The gist of the question seemed to be the (entirely reasonable) point that income shares can and do change over time, and that a changing income share (up or down) is not the same thing as inflation (or deflation). I was a bit surprised at how the Governor answered – he basically didn’t. I’d thought it would be an opportunity for an expansive comment on the rich new research programme the Bank had underway, consistent with the revised mandate (and the rhetoric around it).

But this paper suggests the Bank hasn’t got far at all. There is clearly some interesting exploratory micro-data work going on, but it appears to be of limited reach at best. There are reasonable and interesting questions to ask about why inflation has been so low at surprisingly persistently low interest rates (those are questions we really expect central banks to be answering). There are important questions about why productivity growth in New Zealand has been so poor (for so long), and about why relative to that poor productivity growth wage rises in New Zealand have been quite strong (perhaps more so than in many other countries).

One can mount a reasonable case that those latter questions aren’t a prime concern of the Reserve Bank – you can have price stability with high or low productivity growth, weak or strong labour income shares, and so on (inflation being primarily a monetary policy phenomenon). But when you send one of your senior economists out to the public domain to speak on New Zealand wage inflation in the last decade or so, it is pretty astonishing that none of these considerations even get a mention, and instead you have a whole paper built around a misleading prior, that we should be surprised by how weak wage inflation has been. To the extent there is a problem in New Zealand, it is more that overall economic performance has been poor, and within that underperformance, wage earners have at least held their own.

But I guess that – whatever the facts – isn’t a narrative the Governor would be keen on adopting.