In a blog post the other day, which briefly touched on the activities of the People’s Republic of China in New Zealand, former ACT MP and senior lawyer Stephen Franks observed that

Our colonial forebears gained their colonial power and wealth by suborning the elites of the peoples subjugated more often than with military violence.

I hadn’t particularly thought of it that way before, but of course once one thinks about it for even a moment he is correct about the history, and (I suspect) about the relevance of the parallel to the current situation.

In fact, the parallel came to mind in pondering the latest public speech by Gabs Makhlouf the British ring-in Secretary to the Treasury, who not only qualifies as one of the “elite” but isn’t even someone with a strong ongoing personal interest in the future of ordinary New Zealanders, or even of New Zealand institutions. Of course, even public servants holding as high an office as Secretary to the Treasury don’t make policy – we hold politicians to account for that – but Makhlouf seems to be actively engaged with, and supportive of, the longrunning deference to one of the most evil regimes on the planet, and apparent indifference to the tentacles of that regime in our system and country.

It mightn’t even be quite so annoying if his pandering was supported by decent economic analysis or a compelling understanding of the economic challenges facing New Zealand. But it isn’t. The speech, given at the university in Beijing, is under the title “The role of the China-New Zealand relationship in raising living standards”.

He burbles on about his beloved Living Standards framework, reaching the astonishing conclusion in his final paragraph that

Green mountains and blue rivers are as good as mountains of gold and silver.

Perhaps when you have a secure government income of many hundreds of thousands of dollars a year they are, but not to most New Zealanders – the people who struggle to get by, who’d appreciate the opportunities for better housing, better medical treatment, or even a better holiday. Of course, the environment matters (rather a lot), and greater wealth and productivity has given us cost-effective options to reduce pollution (contrast the pollution levels in London or Beijing). Perhaps we could extend the parallel: uninhabited New Zealand 1000 years ago – beautiful and untouched as it may have been – as good as a reasonably prosperous country today that makes extensive use of natural resources, and which has changed the landscape? Few will think so, but perhaps the Secretary does? If this is the sort of economic analysis governments have been getting, no wonder there is no progress in reversing our relative productivity decline.

Makhlouf goes on at length about the value of international trade and investment, and I can go a reasonable way along that line with him. But it is as if he is talking for a totally different country when he observes enthusiastically that

And back in 1990 the ratio of global trade to world GDP was 30 percent; by 2015 that ratio had doubled to around 60 percent.

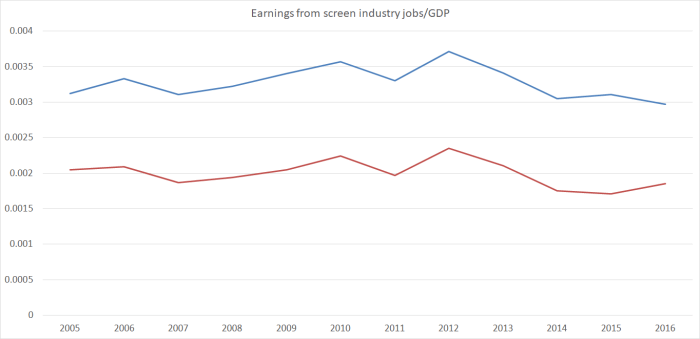

Which is good, but in New Zealand – the country he supposedly represents – the total exports and imports were 52 per cent of GDP in 1990 and 54 per cent last year. We simply haven’t shared at all in the dramatic increases in world trade. And because he seems not to understand that, the Secretary presumably has no credible analysis for what might make a helpful difference in future. As it is, the New Zealand story is even worse than those snapshots suggests: exports as a share of GDP peaked as long ago as 2000, and even exports of services – where the Secretary likes to talk up tourism and export education – peaked as share of GDP in 2002. The services exports share of GDP is now 30 per cent smaller (three percentage points) than it was then.

Then there is one of his tired old lines, claiming that “we” (New Zealand) are “part of the fastest growing region in the world” when, as he delivered his speech in Beijing, he was closer to home in London than to his office in Wellington.

I could go on, but the weaknesses of the Secretary’s economic analysis have been documented in many earlier posts. What appalled in this particular speech was the craven grovelling to the PRC, the total relativisation of our two countries in ways which suggest that he thinks their system, their government, is just as good as ours. (I don’t suppose he really does, but when you are a senior official, backing your government, what you say counts – including no doubt to the PRC authorities. He does the kow-tow)

He begins his speech with the rather empty claim that

Yet there is so much that we have in common.

We are all human beings I guess, but it wasn’t clear what else he had in mind. He tries, not very convincingly, to elaborate.

All of us here want open trade, thriving business, and economic growth. Those things matter for our material wellbeing. But they are only a subset of what contributes to the quality of our lives. I’m sure we share a belief in the importance of good health and education, decent housing, the support of family and friends, a clean natural environment, a safe and peaceful society. We seek that for ourselves and for future generations.

As the Secretary surely knows, the People’s Republic of China has no commitment to open trade, having a highly regulated economy, and tight restrictions on international services trade in particular, and on investment. But what of that broader list of things he thinks we have in common? Perhaps it is fine as far it goes, but he is talking to people in a country whose government has a million people from Xinjiang in concentration and re-indoctrination camps. And for all the Secretary’s talk about wellbeing – and even “social capital” – it is notable that things like free speech, free expression, the ability to change your government, freedom of religion, and even the rule of law – explicitly disavowed not long ago by the PRC Chief Justice – are totally absent from his list. The things that divide free and democratic countries from the PRC regime are huge and important. Perhaps even the sorts of things that might appear in a typical New Zealand assessment of wellbeing? But they, apparently, don’t matter much to the Secretary to the Treasury. He goes on the praise the Belt and Road Initiative – under the aegis of which the previous New Zealand government committed to the (rather frightening) aspiration of “the fusion of civilisations” with the PRC.

In all that he was just warming up. There is later a substantial section of the “NZ-China relationship”, which is almost nauseating in places. Thus

It is a relationship that goes beyond diplomacy and trade. It’s also about the links between people, about investing in our mutual success, and about recognising our shared interests in the world.

Liberty, democracy, the rule of law for example? I guess not. Respect for established international borders? I guess not. Then again, there is this in common, that both China and New Zealand have dramatically (economically) underperformed their near neighbours over the last century of so: in China’s case, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, and in New Zealand’s case Australia.

Then we get this

It hasn’t all been one-way traffic. New Zealander Rewi Alley helped establish the Gung Ho movement in the 1930s and dedicated 60 years of his life to improving the living standards of Chinese workers.

You mean the active member of the Chinese Communist Party and unashamed apologist for its evils (I have one of his books sitting on my desk, co-authored with the dreadful Communist fellow-traveller Wilfred Burchett, written towards the end of the Cultural Revolution celebrating the quality of life in the PRC). Then again, when we have a Chinese Communist Party member in our Parliament what might one expect from our elites?

The Secretary moves on to celebrate PRC foreign investment in New Zealand. He notes, without further comment, that

Over half of the 25 largest Chinese investors in New Zealand are state owned enterprises including Huawei, Yili and Haier.

as if this is a good thing (Treasury not being known for its enthusiasm for SOEs in New Zealand), as if he cares not about the national security threat various allied governments have determined Huawei represents – and note that Huawei likes to represent itself as a private company – and as if he is unaware (or cares not a bit) about the PRC law under which companies (private and public) are required to operate in the interests of the partt-State, at home or abroad. In the best of circumstances, state ownership (and murky ownership) is a recipe for weakened capital allocation disciplines etc, and the Secretary to the Treasury really should know that.

The Secretary goes on

I believe one of the main reasons the China-New Zealand relationship is so close and constructive is because we both recognise the importance of diplomacy.

A line so vacuous it can only mean that New Zealand knows when (almost always) to rollover, never upset Beijing, and so on. And who would want a “close and constructive” relationship with such a tyrannical regime anyway – unless money is now all that matters (surely not so, especially in the Secretary’s wellbeing world. Do these people have no shame?

Channelling the government, the Secretary touches on the Pacific, where the PRC is increasingly active, and in ways that look quite damaging not just to our interests, but to those of the ordinary citizens (although, again, not necessarily the “elites) in those countries. Here is his final line.

We believe it is in everyone’s interest in the region – including New Zealand and China – to encourage sustainable economic development, good governance, respect for sovereignty and the rule of law.

I guess that is really a timid suggestion to the PRC, but they are quite open that they have no time for the rule of law (unless, of course, in their own interests), good governance (surely you’d practice what you preach), let alone “respect for sovereignty” – ask the neighbours in the South China Sea, or Taiwan, the peaceful independent productive democracy.

We believe it is in everyone’s interest in the region – including New Zealand and China – to encourage sustainable economic development, good governance, respect for sovereignty and the rule of law.

Sounding like his countryman, Neville Chamberlain – who did finally come to his senses – we apparently don’t believe in right and wrong, or standing by those who are threatened. The Secretary – and his government – just want to be “honest brokers”. It is a shameful stance.

Perhaps you think I’m being a little unfair to Mr Makhlouf. He is after all just a (very senior) public servant, channelling government policy. But no one forces him to parrot these sorts of lines, and to make public speeches re-emphasising New Zealand’s deference and subservience, all under the mask of “mutual benefits”. Sure, he can’t run an alternative, more challenging, perspective in public, but it is entirely his choice to attach his name to these lines. He is one of the guilty, sacrificing our values, our institutions, while giving cover to the evils of the PRC regime, all for what? A few more dollars for a few more big institutions. In the Secretary’s case there isn’t even the shameful, feeble excuse about political parties “needing” to fund themselves.

Sacrificing our values? Well, in his speech Makhlouf also talked about his living standards framework and how Treasury had gone out to do some weird race-based consultations about what mattered to people. I haven’t read these papers yet but he reported that of their consultation with Asian New Zealanders (emphasis added)

There is a strong belief in the value of collectivism, diligence, responsibility, frugality and recognition of hierarchy in relationships.

Surely, if there is any traditional New Zealand value – and as I noted earlier in the week, I’m not fan of values-test – it is the polar opposite of “recognition of hierarchy in relationships”. But probably Makhlouf, MFAT, and the political elites of all parties would prefer we all knew our place and left all this to them; another deal, more donations, and a refusal to ever stand for the values the Prime Minister sometimes talks about if it might even create even a little awkwardness in Beijing.

Sometimes, moments of hope arise in the strangest places. I’m no fan of Donald Trump, and could only agree with the right-wing US columnist who the other day declared Trump the single most unsuited person to be President in all of US history. And yet the other day, his Vice-President Mike Pence gave a speech on the Administration’s policy towards the PRC that came as distinctly refreshing after reading the Makhlouf effort. I’m not going to excerpt it at length, but for anyone interested I suggest you read it. I was pleasantly surprised by much of it, and have seen fairly positive commentary on it from various Democrtic-leaning China commentators.

But I come before you today because the American people deserve to know that, as we speak, Beijing is employing a whole-of-government approach, using political, economic, and military tools, as well as propaganda, to advance its influence and benefit its interests in the United States.

China is also applying this power in more proactive ways than ever before, to exert influence and interfere in the domestic policy and politics of this country.

Pretty much what Anne-Marie Brady (I’m pretty sure no right-wing Republican) has been saying here, although you will never hear such honesty from our politicians.

Previous administrations made this choice in the hope that freedom in China would expand in all of its forms -– not just economically, but politically, with a newfound respect for classical liberal principles, private property, personal liberty, religious freedom — the entire family of human rights. But that hope has gone unfulfilled.

Gabs Makhlouf claims to believe we have so much in common with the PRC.

Beijing is also using its power like never before. Chinese ships routinely patrol around the Senkaku Islands, which are administered by Japan. And while China’s leader stood in the Rose Garden at the White House in 2015 and said that his country had, and I quote, “no intention to militarize” the South China Sea, today, Beijing has deployed advanced anti-ship and anti-air missiles atop an archipelago of military bases constructed on artificial islands.

Blunt, but unquestionable. And thus utterly unacceptable in New Zealand.

At the University of Maryland, a Chinese student recently spoke at her graduation of what she called, and I quote, the “fresh air of free speech” in America. The Communist Party’s official newspaper swiftly chastised her. She became the victim of a firestorm of criticism on China’s tightly-controlled social media, and her family back home was harassed. As for the university itself, its exchange program with China — one of the nation’s most extensive — suddenly turned from a flood to a trickle.

While in our universities, Confucius Institute advance PRC interests, and our multi-university Contemporary China Research Centre is chaired by someone who chairs a Confucius Institute, advises the PRC on Confucius Institute, and has a range of other interests that could be severely disadvantaged if the PRC were ever upset.

I don’t have any confidence in the Adminstration’s willingness to stick to anything, or in Trump’s temperament in handling a crisis. But at least the US government is willing to call a spade a spade in this area. Ours are determined to see never ill, say nothing ill, while their party leaders (sickeningly) praise the regime, and the party donations keep flowing in.

Sadly, there is a yawning vacuum where courageous and honest political leadership, standing for our system, our values, and (to the extent we can) for the rights and freedoms of people in China, might be. As Stephen Franks put it, it is the elites we have to worry about.

And, in closing, I noticed this link this morning on Anne-Marie Brady’s Twitter account

The article it links is (or at least I found it so) a little difficult to make your way through, but it represents the efforts of some ethnic Chinese New Zealanders not content with successive New Zealand governments’ supine approach to the PRC.