James Shaw, co-leader of the Green Party and Minister for Climate Change (surely Minister against it?), tells us he is working his way through 15000 submissions on the recent climate change consultation document. I’ve done a couple of posts here on the document, and on the NZIER modelling used extensively in it, and I’ve chided both the Minister and his department, NZIER, and the Productivity Commission for simply ignoring the fact that our large-scale non-citizen immigration policy is a discretionary policy measure that drives up New Zealand’s carbon emissions, further increasing the economic cost of any variant of a “net-zero” target the government might choose to adopt. But I didn’t make a submission: there are only so many hours in the week, and it seems pretty clear from some recent broadcast remarks from the Minister that he thinks his own Ministry (for the Environment) is altogether too pessimistic. A net-zero target is, he claims, a huge economic opportunity for New Zealand. Never mind that there is precisely no analysis to support such a claim.

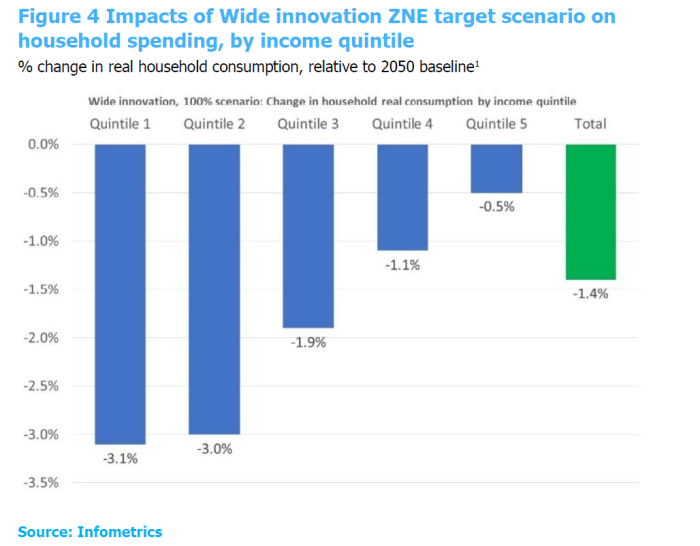

In any good policy development process, one wants to see evidence of a proper cost-benefit analysis having been undertaken. What is the value of the benefits of any actions it is proposed to take, what are the costs of those actions themselves, how uncertain are each of those sets of numbers, and (not unimportantly) how might those costs and benefits change if we were simply to wait a while, or respond gradually (in ways that might, for example, give us more data). That sort of analysis – with inevitable imprecisions – is perhaps all the more important when crusaders are champing at the bit to launch a really major, far-reaching, change in our economy and society, and one with – on the government’s own numbers – really big, adverse (ie falling most heavily on the poorest) distributional effects.

The government consultation document, drawing on the NZIER modelling (with all its limitations), did attempt to outline the costs of adopting a net-zero by 2050 emissions target. The Ministry, in particular, was keen to play down the numbers, but they did report them: best estimates from NZIER were for a loss of GDP of 10 to 22 per cent (ie lower than otherwise). As I noted in my earlier post, I doubt any democratic government has ever consulted on a proposal to reduce the wealth and incomes of its citizens by quite so much.

But the consultation document made no attempt to assess the economic costs (if any) to New Zealand, and New Zealanders, from the sort of climate change that is likely to occur in the absence of (global) policy responses. There doesn’t seem to be any such analysis that has been done anywhere in, or for, the New Zealand public sector. Former Treasury and MBIE official (and now a consultant) Jim Rose highlighted this in a recent Dominion-Post op-ed.

Estimates of the cost of global warming as a percentage of GDP to New Zealand are elusive. I drew a nil response when I asked for that information from James Shaw, the Minister for Climate Change, and from the Ministry for the Environment. Both said such an estimate was too hard to calculate.

As he notes

Fortunately, the OECD rose to the challenge in its 2015 report on The Economic Consequences of Climate Change.

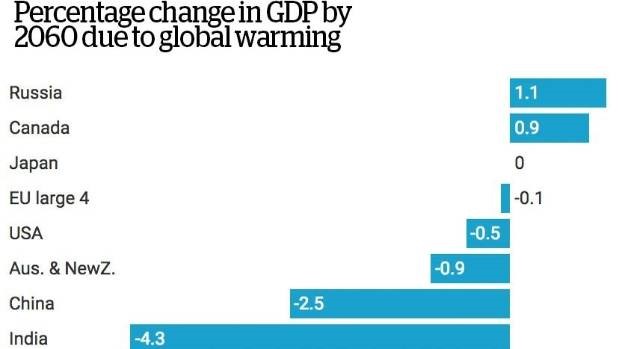

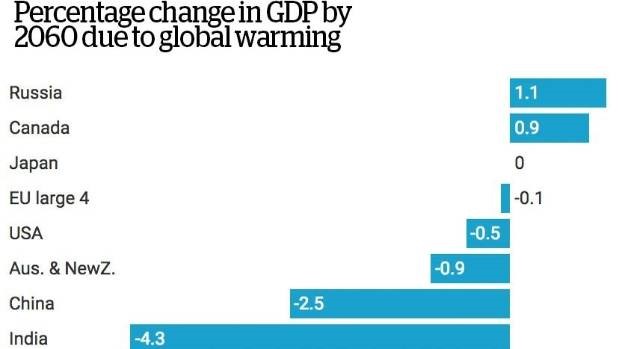

Rose included this chart, drawing on the OECD’s modelling work

Very cold countries are expected to see an economic gain from climate change over the next few decades, and for temperate climate countries it looks like roughly a wash. New Zealand is modelled with Australia, but Australia is a much hotter country, and it seems quite quite reasonable to suppose that the New Zealand numbers is isolation would be basically zero. Given the importance of agriculture in our economy, and that warmer temperatures would improve crop yields etc in many areas, some overall economic gain seems not implausible.

Now, it is quite reasonable to point out that, in some respects, 2060 isn’t that far away, and climate effects seem to be slow to unfold. So the OECD – hardly a bunch of climate change sceptics – also did some modelling on the effects out to 2100. This is from their Executive Summary

Presumably the adverse effects still differ quite markedly by geographic region. But notice two things. First, this OECD modelling suggests that some of these modelled costs are now sunk costs anyway (would happen even if emissions fall to zero as soon as 2060). And second, and more importantly, recall the range of economic costs to New Zealand of adopting a net-zero (by 2050) target: 10 to 22 per cent of GDP. In other words, even if New Zealand were exposed to economic costs of climate change at the upper end of the OECD estimates (10 per cent of GDP by 2100), it still wouldn’t be economically worthwhile to pay a price of 10 to 22 per cent of GDP 50 years earlier to prevent such outcomes. That is basically what the government’s own numbers say.

And it is all even worse than that. After all, on these OECD estimates, getting to net-zero (globally) by 2060 would only prevent half the losses. And since much of modelled adjustment in New Zealand relies on sequestration (planting lots and lots of new forests, almost exclusively on land not currently used for economic purposes) – and that can really only be done once – it isn’t implausible to suppose that the economic costs of maintaining net zero emissions beyond 2050 would only increase further.

But somehow none of this – material from his own ministry, from their consultants, or from the OECD – seems to have any impact on the Minister. He tries to draw strange parallels with the internet

“I think the New Zealand of 2050 will look as similar and as different as the New Zealand of today does to the New Zealand that we had 30 years ago. You’ve got to remember 30 years ago, the same period of time that we’re talking about, the internet did not exist. Didn’t exist, right? But you try and run your school or your home or your community group or your business without the internet today, it’s unimaginable.

“The internet has had a profound impact on our economy, on our lives. Whole new industries have been built off the back of it… but the New Zealand of today still feels in many ways a bit like the New Zealand of 1988.”

All of which is largely true (and the further into middle-age you are, the more 1988 seems like yesterday anyway), but irrelevant. The internet (and associated applications) has been a series of new technologies that have materially changed elements of peoples’ lives. But that is (largely) private sector innovation, and consumer adoption (or not) of the opportunities and technologies. Perhaps a more important comparison the Minister might like to reflect on are areas of demonstrable underperformance since 1988? Our economy (per capita) is better off than in 1988. But, for example, we’ve had among the very worst rates of productivity growth of an advanced country in that 30 year period. Productivity is what opens up options to deal with poverty and all those social issues the Greens say they care about. Or house prices – which have moved from more or less affordable to highly unaffordable in large chunks of the country (largely as a result of well-intentioned policy choices by people with noble aspirations).

Just like James Shaw and the government of which he is now a part. This is what he says about the economics of his proposed net-zero target

He says investing in meeting our climate change goals will be a massive economic boost, rather than a burden.

“What we’re talking about here is a more productive economy, with higher-tech, higher-valued, higher-paid jobs. It’s clearly a cleaner economy where you’ve got lower health care costs, people living in warmer homes, congestion-free streets in Auckland.

“It’s an upgrade to our economy. It’s an investment, you’ve got to put something in, in order to generate that return. If we don’t, the clean-up costs from the impacts of climate change will well exceed the costs of the investment we’ve got to make to avoid the problem in the first place.”

But where is his analysis? Where are his numbers in support of this? There is nothing of the sort in the consultation document, or in the NZIER modelling. Without something of that sort – tracing through the mechanisms he expcts to see these effects – this is all dreamtime stuff, arguably either delusional or worse. There is nothing to demonstrate why we should take seriously the Minister’s claim that markedly shifting pricing (or using regulation to the same end) against key sources of energy, and skewing pricing against our handful of large internationally competitive industries (even, unlikely at this stage, if our competitors were going to do the same thing) would mean we’d all end richer (“massively” so apparently) than if the government hadn’t adopted such policies. It simply doesn’t ring true.

Perhaps the Minister is (deliberately?) confusing two things. The centuries-long era of technological innovation shows no sign of having ended. There will be technologies 50 years from now that few of us can even dream of today. In some cases, they may leave our grandchildren considerably wealthier than we are. In some cases, they are likely to markedly ease the costs of adjusting away from an economic structure that involves large-scale carbon emissions. But that is a quite different thing from supposing/assuming that heavy government intervention, of the sort the government is proposing, will itself make us all a lot richer. And, as I’ve noted previously, even the NZIER modelling numbers already assume into existence big improvements in technology, in turn assuming away what would otherwise be very large economic costs of adjustment.

Perhaps those technology assumptions will themselves prove to conservative. But wouldn’t we be a lot better off waiting to see how the technological opportunities unfold, rather than racing ahead, wishing upon a star, when – on the OECD’s own numbers, the economic costs to New Zealanders of waiting appear likely to be modest (at worst). And lets no forget – and in any circumstances the Green Party rightly wouldn’t let us do so – the distributional impact the government’s own commissioned modelling revealed.

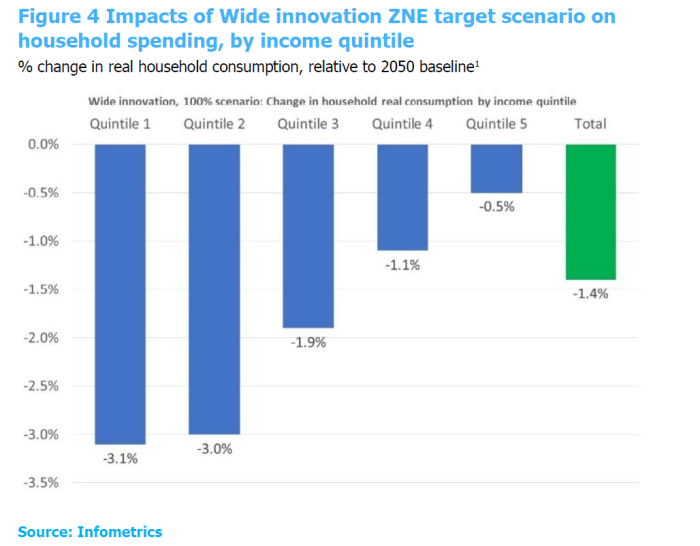

Six times as heavy a burden on the bottom 20 per cent as on the highest-income 20 per cent. Six times.

In his enthusiasm for rushing ahead, beyond any sort of current international commitment, James Shaw cites public opinion

“New Zealanders do want us to lead on climate change. They think our response so far has been inadequate. They think that New Zealand should act even if other countries don’t,” he told Newshub Nation on Saturday, citing a recent survey by IAG.

“They really want us to be ambitious and to do the best we can.”

That survey showed while three-quarters of Kiwis think New Zealand should take action even if other countries don’t, only one in 10 percent think the rest of the world will.

More details of that survey (or not the exact wording of the questions, probably rather leading given the commercial virtue-signalling purposes it appears to have been commissioned for) are here.

Public opinion matters, a lot. The public elect, and oust, governments. But what proportion of the public does the Minister honestly suppose has any sense – even the vaguest sense – of the sort of cost-benefit calculus implicit in combining the OECD estimates (economic costs of climate change) with his government’s own published estimates of the costs of fast New Zealand moves to zero emissions? And the fact that the answer is likely to be well under 5 per cent isn’t really an adverse reflection on the public – ignorant voters and all that – but a reflection on our political parties and official/bureaucratic classes, which have fallen over themselves to avoid sharing such perspectives more widely. The feel-good response to the end-of-the-world-is-nigh rhetoric is hard to stand against; easier to go with the flow, and if anything cheer it on. But pointing out this pretty basic considerations – and they aren’t hard arguments to explain – should perhaps be something political leaders (if the word “leader” means more than just holding office) should do.

My former colleage Ian Harrison, now at Tailrisk Economics, makes a bit of a speciality of digging more deeply into some of the dubious claims that government ministries, and the like, often make (a collection of his papers is here). He has been digging into some of the claims, and the modelling, regarding possible New Zealand emissions targets, and sent me the other day a draft of a paper he is working on, with permission to share a few excerpts.

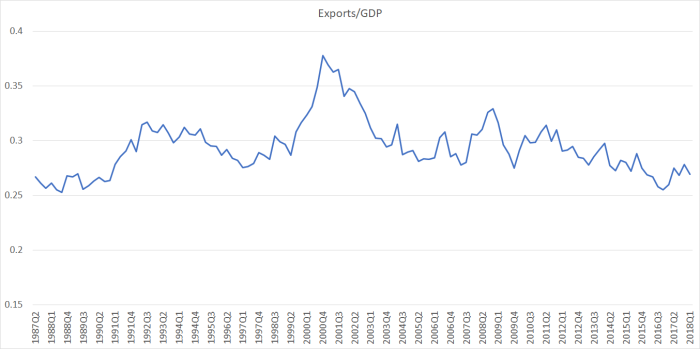

Ian’s draft paper draws attention (more than I have, and more than the report itself does) to the pretty significant reductions in exports in the NZIER modelling. It seems unlikely that a small economy doing less trade with the rest of the world is going be achieving a “massive boost” to prosperity. Ian also draws attention to a point I’ve also made in earlier posts, about where the new forests are likely to go. NZIER assumes that the new forests are on land that currently has little or no economic use. But if agriculture is brought into an ETS (even partially and gradually) and there are substantial carbon credits from forestry sequestration, we could see a large amount of existing farmland converted to forestry. Whatever the possible merits of such a conversion, it would further reduce exports over the decades in which the trees were growing, which in turn would be likely to have implications for the exchange rate (something not dealt with in the NZIER modelling at all).

Ian also draws attention to the way in which both the IPCC’s most recent report on Australasia (a summary of the New Zealand bits is here) does not support the notion that the economic impacts of global warming itself “would be strongly negative, or at least negative at all” this century. He draws attention to a 2012 Ministry of Primary Industries report on the impact of climate change on land-based sectors.

The main purpose of the report was to look at adaptation and resilience issues rather than make an overall assessment of the economic costs and benefits, but two major themes suggest that the overall impact would be positive. The first is that C02 fertilisation will have a major positive impact. The second is that New Zealand farmers are very good at adapting both tactically and more strategically to climate events, which would help mitigate some of the adverse impacts, which are in any event, less quantitatively significant.

Recall that the assumed warming over the 21st is less than the temperature difference between Invercargill and Auckland (and, even setting aside growing conditions, most people would count such a shift as an improvement in the amenity value of their location – certainly true of Wellington).

Much of the thrust of Ian’s paper is scepticism about the case – touted by the government, with public opinion support for the time being – for acting early and aggressively. One argument made in official papers is that acting early reduces the risk of later sudden drastic shocks, but the basic logic of this argument seems flawed, given the absence of technology to deal with some of the major sources of New Zealand emissions.

Logic would suggest that in New Zealand more time would reduce those risks. In particular, reducing animal methane emissions per animal is challenging and will take time. The NZIER report shows that if we pursue a zero emissions target without a technical solution the impact on the pastoral sector would be devastating with output falling by 70 percent, from baseline projections, by 2050.

Another argument is that by acting early by will get economic advantages from being early into emerging technologies.

This argument is overblown and reflects wishful thinking rather than hard analysis. The reduction in emissions will not involve (much) marketable technological innovation. We will mainly grow more trees. The rest of the world already knows how to do that. We will import electric cars leveraging off innovation elsewhere. Norway has been an earlier adopter of electric cars but no one has suggested that Norway has innovated to produce better electric cars. We may close down some carbon intensive industries such as iron and steel and cement manufacturing. Painful, but doesn’t require much innovation that we can sell to the rest of the world.

And then, of course, there is the incredible “moral leadership” argument, recently also advanced – stepping well out of his field – by the Reserve Bank Governor.

Again this is wishful thinking. Does anyone seriously expect the countries that matter: the US, China and India, to be influenced by what New Zealand does.

And if, in some sense, rich countries probably should take some sort of lead in dealing with global problems

It is generally accepted that the rich countries should take the lead in reducing greenhouse emissions. However, New Zealand is not really a rich country, sitting on the margin of being an upper middle-income country. This weakens the case for New Zealand bearing a disproportionate share of the mitigation burden, particularly if the result is to push us more firmly into middle-income territory.

And there is a reminder of the elephant in the room that not even the Greens seem yet to be willing to address. Emissions from international travel and shipping aren’t in the international emissions numbers, but it doesn’t change the facts. There are no good alternative technologies are present, and yet international shipping and aviation are probably more important to New Zealand (given distance, and being an island) than for most advanced countries.

Setting out to, in some sense, “lead the world” in this area is a recipe for severely impairing the future living standards of our own people. Perhaps the warm inner glow of the “feel good” – which would no doubt linger long among Greens supporters, well after most New Zealanders were living with the economic consequences – should be added to Treasury wellbeing dashboard? But it is likely to take an awfully large amount of “feel good” to compensate for the lost opportunities – for rich and poor alike – of wilfully giving up 10 to 22 per cent of future GDP (on the government’s own numbers).