In Christchurch tomorrow evening, Anne Krueger is giving the 2018 Condliffe Lecture.

Krueger is an eminent figure in economics, now in her 80s. She had a distinguished academic career, specialising mostly in trade and development issues, and she also spent time as first Chief Economist at the World Bank, and then later (until 2006) as first deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund. (My lasting impression of her, as an international bureaucrat, was the day she declaimed at a Board retreat about the challenges the IMF faced as a small organisation – at the time staff numbers totalled about 3000.)

According to Canterbury University

In the University of Canterbury’s 2018 Condliffe Lecture, Anne Krueger will explore the topic: “Is it harder or easier to develop rapidly than it was a half century ago?” in her talk on development and economic growth.

She will argue, we are told

“In this lecture, I shall argue that while the future is never entirely foreseeable, there are a number of considerations that point to greater ease of development now than in the past. These include: the diminishing rate of increase in populations in most low income countries; the fact that much more is understood now (albeit still imperfectly) about development (and especially how not to achieve it); that global markets are much larger; and obtaining information of all kinds is much easier.”

There are also some technological advances that make development easier: mobile phones; continuing discoveries of improved technology in agriculture; advances in materials sciences; and so on.

I hope a copy of her text is made available.

I’m not sure how often Professor Krueger has been to New Zealand, but there is a record of a visit in 1985, when she was at the World Bank. She delivered a lecture under Treasury’s Public Information Programme, under the heading Economic Liberalization Experiences – The Costs and Benefits (if anyone wants a copy, it appears to be held in the University of Auckland library, but isn’t online anywhere).

As she noted

As a newcomer to the New Zealand scene, it would be foolhardy of me to attempt any assessment of the policies implemented in support of the New Zealand quest for economic liberalization. It may be useful, however, to discuss what liberalization more generally is usually about, and to attempt to draw on the experience of other countries for lessons and insights that may potentially be applicable – by those of you more knowledgeable about the situation here than I – in evaluating the progress of liberalization in New Zealand.

It is a very substantial lecture (18 pages of text), drawing on the experiences in previous decades of a wide range of other countries grappling with twin challenges of stabilisation (inflation, fiscal etc) and liberalisation.. The small bit I wanted to highlight – which saddened me when I first read it a few years ago, and still does, from a “what might have been” perspective – was about the exchange rate.

Two important lessons emerge from the Southern Cone [of Latin America] experience: failure to maintain the real exchange rate during and after liberalisation is an almost sure-fire formula for major difficulties and the defeat of the effort. The reason for this is that a liberalization effort aimed at opening up the economy must induce more international trade; it is not enough that there be more imports, there must be more exports. Since the exchange rate is the most powerful policy instrument with which to provide incentives for exporters, its maintenance at realistic levels which provide an incentive to producers to export is crucial to success.

and a few pages later she returns to the theme

“In particular, the exchange rate regime must provide an adequate return to producers of tradable goods, particularly to exporters”

At the time, this would have resonated strongly with senior New Zealand officials. One of the starkest memories of my first year at the Reserve Bank, fresh out of university, was being minute secretary to a meeting in late 1984 attended by the top tiers of the Reserve Bank and The Treasury. It was a just a few months after the big devaluation that ushered in the reform programme: senior officials were explicitly united in emphasising how vital it was to “bed-in” the lower exchange rate, and ensure that the real exchange rate stayed low.

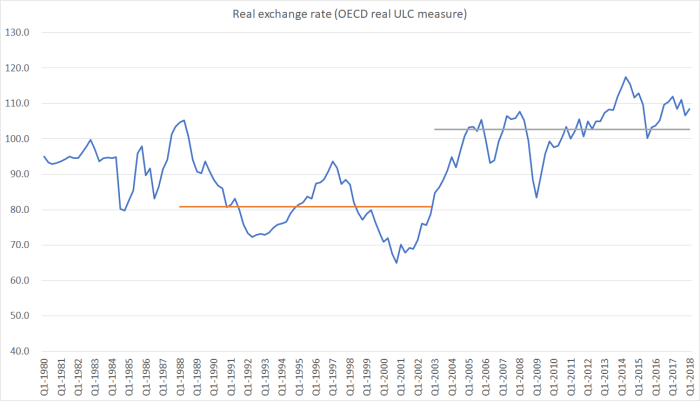

You can see that 1984 devaluation in this chart of the real exchange rate I ran a few weeks ago.

In fact, the gains from the devaluation were swallowed up very quickly by inflation. When we finally got on top of inflation, the real exchange rate did average lower for some time – and during those years the tradables sector of the economy (and export and import shares) were growing relatively strongly. But for the last 15 years, the real exchange rate has averaged even higher than it was prior to the start of the liberalisation programme. It hasn’t been taken higher by a stellar productivity performance.

It shouldn’t be any surprise that the export and import shares of GDP have fallen back, and that there has been no growth at all in per capita tradables sector GDP this century. Successful sustained catch-up growth – of the sort New Zealand desperately needs – doesn’t come about that way.

Perhaps some attendee might ask Professor Krueger for any reflections on her 1985 comments about the importance of the real exchange rate in light of New Zealand’s disappointing economic experience since then. And linking back to the topic of her 2018 lecture, can we now catch-up fast, having failed so badly to do for the last 30+ years? Fixing the badly misaligned real exchange rate, a symptom of imbalances but which is skewing incentives all over the economy, seems likely to be imperative. New Zealand just isn’t that different: wasn’t then, isn’t now.